Caria

Caria (/ˈkɛəriə/; from Greek: Καρία, Karia, Turkish: Karya) was a region of western Anatolia extending along the coast from mid-Ionia (Mycale) south to Lycia and east to Phrygia.[1] The Ionian and Dorian Greeks colonized the west of it and joined the Carian population in forming Greek-dominated states there. The inhabitants of Caria, known as Carians, had arrived there before the Ionian and Dorian Greeks. They were described by Herodotus as being of Minoan descent,[2] while the Carians themselves maintained that they were Anatolian mainlanders intensely engaged in seafaring and were akin to the Mysians and the Lydians.[2] The Carians did speak an Anatolian language, known as Carian, which does not necessarily reflect their geographic origin, as Anatolian once may have been widespread. Also closely associated with the Carians were the Leleges, which could be an earlier name for Carians or for a people who had preceded them in the region and continued to exist as part of their society in a reputedly second-class status.

| Caria (Καρία) | |

|---|---|

| Ancient Region of Anatolia | |

Theater in Caunos | |

| Location | Southwestern Anatolia |

| State existed | 11th–6th century BC |

| Language | Carian |

| Biggest city | Halicarnassus |

| Roman province | Asia |

Location of Caria within the classical regions of Asia Minor/Anatolia | |

Municipalities of Caria

Cramer's detailed catalog of Carian towns in classical Greece is based entirely on ancient sources.[3] The multiple names of towns and geomorphic features, such as bays and headlands, reveal an ethnic layering consistent with the known colonization.

Coastal Caria

Coastal Caria begins with Didyma south of Miletus,[4] but Miletus had been placed in the pre-Greek Caria. South of it is the Iassicus Sinus (Güllük Körfezi) and the towns of Iassus and Bargylia, giving an alternative name of Bargyleticus Sinus to Güllük Körfezi, and nearby Cindye, which the Carians called Andanus. After Bargylia is Caryanda or Caryinda, and then on the Bodrum Peninsula Myndus (Mentecha or Muntecha), 56 miles (90 km) from Miletus. In the vicinity is Naziandus, exact location unknown.

On the tip of the Bodrum Peninsula (Cape Termerium) is Termera (Telmera, Termerea), and on the other side Ceramicus Sinus (Gökova Körfezi). It "was formerly crowded with numerous towns."[5] Halicarnassus, a Dorian Greek city, was planted there among six Carian towns: Theangela, Sibde, Medmasa, Euranium, Pedasa or Pedasum, and Telmissus. These with Myndus and Synagela (or Syagela or Souagela) constitute the eight Lelege towns. Also on the north coast of the Ceramicus Sinus is Ceramus and Bargasus.

On the south of the Ceramicus Sinus is the Carian Chersonnese, or Triopium Promontory (Cape Krio), also called Doris after the Dorian colony of Cnidus. At the base of the peninsula (Datça Peninsula) is Bybassus or Bybastus from which an earlier names, the Bybassia Chersonnese, had been derived. It was now Acanthus and Doulopolis ("slave city").

South of the Carian Chersonnese is Doridis Sinus, the "Gulf of Doris" (Gulf of Symi), the locale of the Dorian Confederacy. There are three bays in it: Bubassius, Thymnias and Schoenus, the last enclosing the town of Hyda. In the gulf somewhere are Euthene or Eutane, Pitaeum, and an island: Elaeus or Elaeussa near Loryma. On the south shore is the Cynossema, or Onugnathos Promontory, opposite Symi.

South of there is the Rhodian Peraea, a section of the coast under Rhodes. It includes Loryma or Larymna in Oedimus Bay, Gelos, Tisanusa, the headland of Paridion, Panydon or Pandion (Cape Marmorice) with Physicus, Amos, Physca or Physcus, also called Cressa (Marmaris). Beyond Cressa is the Calbis River (Dalyan River). On the other side is Caunus (near Dalyan), with Pisilis or Pilisis and Pyrnos between.

Then follow some cities that some assign to Lydia and some to Caria: Calynda on the Indus River, Crya, Carya, Carysis or Cari and Alina in the Gulf of Glaucus (Katranci Bay or the Gulf of Makri), the Glaucus River being the border. Other Carian towns in the gulf are Clydae or Lydae and Aenus.

Inland Caria

.jpg.webp)

At the base of the east end of Latmus near Euromus, and near Milas where the current village Selimiye is, was the district of Euromus or Eurome, possibly Europus, formerly Idrieus and Chrysaoris (Stratonicea). The name Chrysaoris once applied to all of Caria; moreover, Euromus was originally settled from Lycia. Its towns are Tauropolis, Plarasa and Chrysaoris. These were all incorporated later into Mylasa. Connected to the latter by a sacred way is Labranda. Around Stratonicea is also Lagina or Lakena as well as Tendeba and Astragon.

Further inland towards Aydin is Alabanda, noted for its marble and its scorpions, Orthosia, Coscinia or Coscinus on the upper Maeander and Halydienses, Alinda or Alina. At the confluence of the Maeander and the Harpasus is Harpasa (Arpaz). At the confluence of the Maeander and the Orsinus, Corsymus or Corsynus is Antioch on the Maeander and on the Orsinus in the mountains a border town with Phrygia, Gordiutichos ("Gordius' Fort") near Geyre. Founded by the Leleges and called Ninoe it became Megalopolis ("Big City") and Aphrodisias, sometime capital of Caria.

Other towns on the Orsinus are Timeles and Plarasa. Tabae was at various times attributed to Phrygia, Lydia and Caria and seems to have been occupied by mixed nationals. Caria also comprises the headwaters of the Indus and Eriya or Eriyus and Thabusion on the border with the small state of Cibyra.

History

.jpg.webp)

Pre-Classical Greek states and people

The name of Caria also appears in a number of early languages: Hittite Karkija (a member state of the Assuwa league, c. 1250 BC), Babylonian Karsa, Elamite and Old Persian Kurka. According to Herodotos, the legendary King Kar, son of Zeus and Creta, founded Caria and named it after him, and his brothers Lydos and Mysos founded Lydia and Mysia, respectively. It is suggested that the mythological link between Caria and Minos' Crete was for the purpose of proving the Hellenic lineage of the Carians, who disputed such association by maintaining that they were autochthonous inhabitants of the mainland.[6] The Carians refer to the shrine of Zeus at Mylasa, which it shared with the Mysians and Lydians, proving that they were brother races.[7]

Sovereign state hosting the Greeks

Caria arose as a Neo-Hittite kingdom around the 11th century BC. The coast of Caria was part of the Doric hexapolis ("six-cities") when the Dorians arrived after the Trojan War, in c. 13th century BC, in the last and southernmost waves of Greek migration to western Anatolia's coastline and occupied former Mycenaean settlements such us Knidos and Halicarnassos (near present-day Bodrum). Herodotus, the famous historian was born in Halicarnassus during the 5th century BC. Greek apoikism (a form of colonization) in Caria took place mostly on the coast, as well as in the interior in great number, and groups of cities and towns were organized in local federations.

Homer's Iliad records that at the time of the Trojan War, the city of Miletus belonged to the Carians, and was allied to the Trojan cause.

Lemprière notes that "As Caria probably abounded in figs, a particular sort has been called Carica, and the words In Care periculum facere, have been proverbially used to signify the encountering of danger in the pursuit of a thing of trifling value." The region of Caria continues to be an important fig-producing area to this day, accounting for most fig production in Turkey, which is the world's largest producer of figs.

An account also cited that Aristotle claimed Caria, as a naval empire, occupied Epidaurus and Hermione and that this was confirmed when the Athenians discovered the graves of the dead from Delos.[8] Half of it were identified as Carians based on the characteristics of the weapons they were buried with.[8]

Lydian province

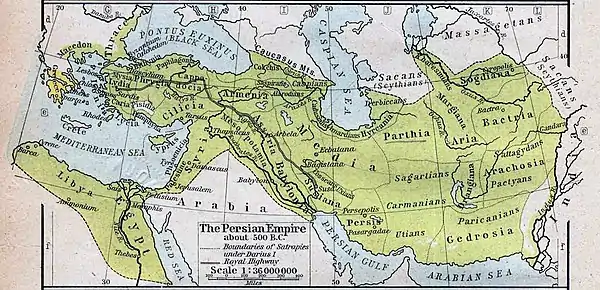

The expansionism of Lydia under Croesus (560-546 BC) incorporated Caria briefly into Lydia before it fell before the Achaemenid advance.

Persian satrapy

Caria was then incorporated into the Persian Achaemenid Empire as a satrapy (province) in 545 BC. The most important town was Halicarnassus, from where its sovereigns, the tyrants of the Lygdamid dynasty (c.520-450 BC), reigned. Other major towns were Latmus, refounded as Heracleia under Latmus, Antiochia, Myndus, Laodicea, Alinda and Alabanda. Caria participated in the Ionian Revolt (499–493 BC) against the Persian rule.[9]

During the Second Persian invasion of Greece (480-479 BC), the cities of Caria were allies of Xerxes I and they fought at the Battle of Artemisium and the Battle of Salamis, where the Queen of Halicarnassus Artemisia commanded the contingent of 70 Carian ships. Themistocles, before the battles of Artemisium and Salamis, tried to split the Ionians and Carians from the Persian coalition. He told them to come and be on his side or not to participate at the battles, but if they were bound down by too strong compulsion to be able to make revolt, when the battles begin, to be purposely slack.[11] Plutarch in his work, The Parallel Lives, at The Life of Themistocles wrote that: "Phanias (Greek: Φαινίας), writes that the mother of Themistocles was not a Thracian, but a Carian woman and her name was Euterpe (Eυτέρπη), and Neanthes (Νεάνθης) adds that she was from Halicarnassus in Caria.".[12]

After the unsuccessful Persian invasion of Greece in 479 BC, the cities of Caria became members of the Athenian-led Delian League, but then returned to Achaemenid rule for about one century, from around 428 BC. Under Achaemenid rule, the Carian dynast Mausolus took control of neighbouring Lycia, a territory which was still held by Pixodarus as shown by the Xanthos trilingual inscription.

The Carians were incorporated into the Macedonian Empire following the conquests of Alexander the Great and the Siege of Halicarnassus in 334 BC.[13]

Halicarnassus was the location of the famed Mausoleum dedicated to Mausolus, a satrap of Caria between 377–353 BC, by his wife, Artemisia II of Caria. The monument became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, and from which the Romans named any grand tomb a mausoleum.

Macedonian empire

Caria was conquered by Alexander III of Macedon in 334 BC with the help of the former queen of the land Ada of Caria who had been dethroned by the Persian Empire and actively helped Alexander in his conquest of Caria on condition of being reinstated as queen. After their capture of Caria, she declared Alexander as her heir.[13]

Roman-Byzantine province

.jpg.webp)

As part of the Roman Empire the name of Caria was still used for the geographic region but the territory administratively belonged to the province of Asia. During the administrative reforms of the 4th century this province was abolished and divided into smaller units. Caria became a separate province as part of the Diocese of Asia.

Christianity was on the whole slow to take hold in Caria. The region was not visited by St. Paul, and the only early churches seem to be those of Laodicea and Colossae (Chonae) on the extreme inland fringe of the country, which itself pursued its pagan customs. It appears that it was not until Christianity was officially adopted in Constantinople that the new religion made any real headway in Caria.[14]

Dissolution under the Byzantine Empire and passage to Turkish rule

In the 7th century, Byzantine provinces were abolished and the new military theme system was introduced. The region corresponding to ancient Caria was captured by the Turks under the Menteşe Dynasty in the early 13th century.

There are only indirect clues regarding the population structure under the Menteşe and the parts played in it by Turkish migration from inland regions and by local conversions, but the first Ottoman Empire census records indicate, in a situation not atypical for the region as a whole, a large Muslim (practically exclusively Turkish) majority reaching as high as 99% and a non-Muslim minority (practically exclusively Greek supplemented with a small Jewish community in Milas) as low as one per cent.[15] One of the first acts of the Ottomans after their takeover was to transfer the administrative center of the region from its millenary seat in Milas to the then much smaller Muğla, which was nevertheless better suited for controlling the southern fringes of the province. Still named Menteşe until the early decades of the 20th century, the kazas corresponding to ancient Caria are recorded by sources such as G. Sotiriadis (1918) and S. Anagiostopoulou (1997) as having a Greek population averaging at around ten per cent of the total, ranging somewhere between twelve and eighteen thousand, many of them reportedly recent immigrants from the islands. Most chose to leave in 1919, before the population exchange.

Notes

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- The Histories, Book I Section 171.

- Cramer (1832), pages 170-224.

- Page 170.

- Page 176.

- Unwin, Naomi Carless (2017). Caria and Crete in Antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 6. ISBN 9781107194175.

- Herodotus; Romm, James (2014). Histories. Translated by Mensch, Pamela. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing. p. 65. ISBN 9781624661143.

- Ridgeway, William (2014). The Early Age of Greece, Volume I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 269. ISBN 9781107434585.

- Herodotus Histories Book 5: Terpsichore

- On the identification with Artemisia: "...Above the ships of the victorious Greeks, against which Artemisia, the Xerxes' ally, sends fleeing arrows...". Original German description of the painting: "Die neue Erfindung, welche Kaulbach für den neuen hohen Beschützer zu zeichnen gedachte, war wahrscheinlich "die Schlacht von Salamis“. Ueber den Schiffen der siegreichen Griechen, gegen welche Artemisia, des Xerxes Bundesgenossin, fliehend Pfeile sendet, sieht man in Wolken die beiden Ajaxe" in Altpreussische Monatsschrift Nene Folge p.300

- Herodotus Histories Book 8: Urania [19,22]

- Themistocles By Plutarch "Yet Phanias writes that the mother of Themistocles was not of Thrace, but of Caria, and that her name was not Abrotonon, but Euterpe; and Neanthes adds farther that she was of Halicarnassus in Caria."

- Gagarin, Michael (2010). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome. Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 9780195170726.

- Bean, George E. (2002). Turkey beyond the Maeander. London: Frederick A. Praeger. ISBN 0-87471-038-3.

- Muhammet Yazıcı (2002). "XVI. Yüzyılda Batı Anadolu Bölgesinde (Muğla, İzmir, Aydın, Denizli) Türkmen Yerleşimi ve Demografik Dağılım (Turkmen Settlement and the Demographic Distribution of Western Anatolia in the 16th century), pp. 124-142 for Menteşe Subprovince" (PDF). Muğla University. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2011.

Bibliography

- Bean, George E. (1971). Turkey beyond the Maeander. London: Frederick A. Praeger. ISBN 0-87471-038-3.

- Cramer, J.A. (1832). Geographical and Historical Description of Asia Minor; with a Map: Volume II. Oxford: University Press. Section X Caria. Downloadable Google Books.

- Herodotus (1910) [original c. 440 BC]. . Translated by George Rawlinson – via Wikisource.

Further reading

- Olivier Henry and Koray Konuk, (eds.), KARIA ARKHAIA ; La Carie, des origines à la période pré-hékatomnide (Istanbul, 2019). 604 pages. ISBN 978-2-36245-078-5.

- Riet van Bremen and Jan-Mathieu Carbon (ed.),Hellenistic Karia: Proceedings of the First International Conference on Hellenistic Karia, Oxford, 29 June-2 July 2006 (Talence: Ausonius Editions, 2010). (Etudes, 28).

- Lars Karlsson and Susanne Carlsson, Labraunda and Karia (Uppsala, 2011).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caria. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Caria. |