Lyttelton Harbour

Lyttelton Harbour / Whakaraupō is one of two major inlets in Banks Peninsula, on the coast of Canterbury, New Zealand; the other is Akaroa Harbour on the southern coast.

It enters from the northern coast of the peninsula, heading in a predominantly westerly direction.

Approximately 15 kilometres (9.3 mi) in length from its mouth to Teddington, the harbour sits in the erosion caldera of the ancient Lyttelton Volcano,[1] the steep sides of which form the Port Hills on its northern shore.[2]

The harbour's main population centre is Lyttelton, which serves the city of Christchurch, linked with Christchurch by the single-track Lyttelton rail tunnel (opened 1867), a two lane road tunnel (opened 1964) and two roads over the Port Hills. Diamond Harbour lies to the south and the Māori village of Rāpaki to the west. At the head of the harbour is the settlement of Governors Bay. The reserve of Quail Island is near the harbour head and Ripapa Island is just off its south shore at the entrance to Purau Bay.

The harbour provides access to a busy commercial port at Lyttelton which today includes a petroleum storage facility and a modern container and cargo terminal.[3]

Hector's dolphins, a species endemic to New Zealand, and New Zealand fur seals live in the harbour.

Toponymy

The official place name for Lyttelton Harbour is the dual English/Māori place name Lyttelton Harbour / Whakaraupō.[4] However, this dual name is usually only used on maps or official documents. This dual name is a result of enactment of Section 269 and Schedule 96 of the Ngai Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998.

In Māori the harbour is known as Te Whakaraupō, which translates as Bay of raupō.[5][4] This name came from a swamp of Raupō reed that grew prolifically in the vicinity of Ōhinetahi, or Governor's Bay, at the head of the harbour.[6][7] An alternative spelling, found in older sources, is Whangaraupo, meaning Bay (or harbour) of the Raupo reeds.[8] Captain Stokes of HMS Acheron, who lead a survey of the harbour and surrounding lands in 1849, preferred to use the name Wakaraupo Bay to the then current English name of Port Cooper.[9] However, Stokes preferred name was not used when the harbour was officially renamed Port Victoria upon became a Port of Entry in August 1849.[10] The New Zealand Pilot of 1875, which is based on Stokes survey, gives the Māori place name as Tewhaka.[11]

Commonly Lyttelton Harbour is used, especially in documents meant for a general public audience or in everyday conversation. While this name is not official, it is well recognised and was the name used to refer to the harbour prior to 1998.[12] How the harbour acquired this name is somewhat unclear. John Robert Godley is reported using this name in a speech to the Canterbury Association in 1853. In 1858, it appears officially when describing the electoral boundaries for the Town of Lyttelton, even though that was not the official name of the harbour. The Canterbury Provincial Council established a Lyttelton Harbour Commission in the early 1860s, while the Lyttelton Harbour Board came into existence in 1877, after the Provinces were abolished. Even so, the harbour has been known by other names.

The common original European name for the harbour was Port Cooper, after Daniel Cooper. This name was in common usage by the mid-1840s and was used as a brand name for farm produce from Banks Peninsula and the Dean's farm on the Canterbury Plains.

The name Port Cooper was officially changed and declared to be Port Victoria when it became a Port of Entry in 1849.[10] The Admiralty chart of Lyttelton Harbour, surveyed in 1849, refers to Port Lyttelton or Victoria and sailing instructions in the New Zealand Pilot, of 1875, notes the former name of Port Cooper under the entry for the same.[11] While the official name appeared on Canterbury Association maps of the time, the name Port Victoria does not seem to have immediately achieved widespread usage. Charlotte Godley still refers to Port Cooper in her 1850 letters. The surveyors under Joseph Thomas who surveyed Canterbury in the late 1848 and during 1849 did name the harbour Port Victoria on their maps, after the monarch of the United Kingdom, but the name did not find common acceptance. The name was officially changed to Lyttelton Harbour in 1858, in honour of George William Lyttelton, who was the chairman of the Canterbury Association.[13]

Another less common early name was Cook's Harbour, based on the early explorations by James Cook; the equivalent naming convention referred to Akaroa Harbour as Bank's Harbour after the botanist Joseph Banks.[14]

A treaty settlement in 1998 gave the harbour its official dual name by enactment of the Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998.[15]

History

King Billy Island was a source of sandstone for Māori that was used for grinding stone including pounamu (greenstone).[16][17] Early European settlers used the adjacent Quail Island as a leper colony in 1918–25.[3] Quail Island is now a nature reserve.[3]

Fort Jervois was built on the island of Rīpapa in 1885–95.[3] Rīpapa was used in World War I to intern German nationals as enemy aliens, the most notable being Count Felix von Luckner.

In 1877 the Lyttelton Harbour Board (now Lyttelton Port Company) started building an inner harbour,[3] and in 1895 the Union Steamship Company of New Zealand started a steamship service on the 200-nautical-mile (370 km) route between here and Wellington.[18] From 1907 it was worked with turbine steamships and from 1933 it was named the "Steamer Express".[18]

However, in 1962 New Zealand Railways started the Interislander ferry service on the 55-nautical-mile (102 km) route between Picton and Wellington. This competing service not only offered a shorter crossing but also used diesel ships that had lower running costs than the Union Company's turbine steamers. The wreck of the Steamer Express TEV Wahine in 1968 was a setback for the Lyttelton service but the Union Company introduced a new ship, TEV Rangatira, in 1972.[18] She lost money, survived on a Ministry of Transport subsidy from 1974 and was withdrawn in 1976,[18] leaving the Interislander's Picton route to continue the ferry link between the two islands.

Geography

Lyttelton Harbour is formed from the eroded caldera of an ancient volcano that has been flooded by the sea. The volcano is just one of several eruptive centres that formed Banks Peninsula. Lyttelton Harbour and Port Levy share a common entrance about 2-nautical-mile (4-kilometre) wide, between Godley Head and Baleine Point, with Adderley Head set back slightly.[11] The entrance lies 2.5 nautical miles (4.6 kilometres) from Sumner beach at the south east end of the sandy beaches of Pegasus Bay.[11] From the entrance the harbour runs in West-South-West direction for 7 nautical miles (13 kilometres) with the port of Lyttelton being 4 nautical miles (7 kilometres) up the harbour from the heads, lies on the northern shore.[11] Between the heads the harbour is 8 fathoms (15 metres) deep which gradually reduces to 3.5 fathoms (6 metres) in the vicinity of Lyttelton port.[11] The bottom of mostly soft mud and the only significant navigation hazard between the heads and the port is Parson Rock, a detached submerged rock pinnacle, which is marked, on the south side of the harbour about 200 metres north of Ripapa Island.[11][19] The shipping channel has been dredged so the port can cope with larger container ships.[20]

The prevailing winds in Lyttelton Harbour are from the north-east and south-west.[11] South-west gales can be very violent and have been known to drive ships at anchor ashore from as early as 1851.[21][22][11] In October 2000, 32 boats were sunk and a marina destroyed in one southerly storm with sustained winds of 130 kilometres per hour (70 kn).[23][24] In strong northerly winds a heavy swell rolls up the harbour.[11]

Bays and headlands

Working around the harbour from Godley Head to Adderley Head one encounters:[25]

- Mechanics Bay

- Mechanics Bay is where supplies for the Godley Head lighthouse were landed.

- Breeze Bay

- Livingstone Bay

- Otokitoki / Gollans Bay

- This bay is below Evans Pass. Gollan was one of the surveyors of the harbour.

- Battery Point

- Polhill's Bay

- Which has been completely reclaimed for Cashin Quay.

- Sticking Point

- This is where construction of the Sumner Road stopped when it encountered difficult rock.

- Officers Point

- Erskine Bay

- The Port of Lyttelton occupies this bay.

- Tapoa / Erskine Point

- Magazine Bay

- Corsair Bay

- A popular bay for swimming at.

- Cass Bay

- Thomas Cass was one of the surveyors of the harbour.

- Raupaki Bay

- Governors Bay

- Kaitangata / Mansons Peninsula

- Head of the Bay

- Moepuku Point

- Te Wharau / Charteris Bay

- Hays Bay

- Kaioruru / Church Bay

- Pauaohinekotau Head

- Te Waipapa / Diamond Harbour

- Stoddard Point

- Purau Bay

- Inainatua / Pile Bay

- Deep Gully Bay

- Te Pohue / Camp Bay

- Waitata / Little Port Cooper

- Formerly a whaling station and later a pilot station.

Islands

- Aua / King Billy Island

- Aua / King Billy Island is a small island between Quail Island and the adjacent headland of Moepuku Point. In the past it has also been called Little Quail Island.

- Otamahua / Quail Island

- Officially bearing the dual name Otamahua / Quail Island, the island is usually known in English as Quail Island.[26][27] It acquired this name after an 1842 incident when Captain W Mein Smith flushed some native Quail while out walking here to complete a sketch he was drawing of the island.[26] The Maori name Otamahua means eggs of the sea fowl.[26]

- Kamautaurua Island

- Kamautaurua Island was previously known as Kamautaurua or Shag Reef.[28][29] In December 1862, the cutter Dolphin capsized and wrecked on the reef into an unfavourable wind and tide when returning from further up the harbour with a load of lime.[30][29]

- Ripapa Island

- Also known as Ripa Island. About 200 metres (219 yards) north of the island lies Parson Rock, a submerged rock pinnacle that is covered by about 2.4 metres (8 feet) of water at low tide.[11][19] The rock has been known by this name since the 1800s.[19]

In popular culture

Paul Theroux described Lyttelton Harbour as "long and lovely, a safe anchorage" in The Happy Isles of Oceania.[31]

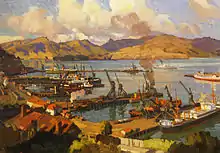

Lyttelton Harbour as seen from Mount Cavendish |

View towards entrance of Lyttelton Harbour |

References

- Hampton, S.J.; J.W. Cole (March 2009). "Lyttelton Volcano, Banks Peninsula, New Zealand: Primary volcanic landforms and eruptive centre identification". Geomorphology. 104 (3–4): 284–298. Bibcode:2009Geomo.104..284H. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2008.09.005.

- "Geology of the Provinces of Canterbury and Westland, New Zealand" (web). New Zealand Texts Collection. NZETC. 1879. Retrieved 23 July 2010.

- "Page 12 – Lyttelton Harbour". Story: Canterbury places. Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. 13 July 2012.

- "Place name detail: Lyttelton Harbour/Whakaraupō". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "NZMS 346/2 Te Wai Pounamu, The Land and its People". www.linz.govt.nz. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Puna Korero Whenua The Department of Survey and Land Information for the Ngā Pou Taunaha o Aotearoa New Zealand Geographic Board. 1995. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Ōhinetahi — Governor's Bay". my.christchurchcitylibraries.com. Christchurch City Libraries. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Te Whakaraupō – Lyttelton Harbour". Christchurch City Libraries. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- Taylor, W. A. (1950). "Port Cooper or Whangaraupo — (Bay of the Raupo Reeds)". Lore and History of the South Island Maori. Christchurch: Bascands Ltd: 57–63. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Stokes, John Lort (24 April 1850). "... extract of a private letter from Captain Stokes of H. M. Steamer Acheron, to. Sir George Grey relating to the district of Port Cooper ... May 4, 1849". New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian. VI (493). Wellington, New Zealand. p. 3. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

... that locality, commonly named Port Cooper, by me, Wakaraupo Bay.

- "Page 4 Advertisements Column 2". New Zealand Spectator and Cook's Strait Guardian. V (420). Wellington, New Zealand. 11 August 1849. p. 4. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

Colonial Secretary's Office, Wellington, 9th August, 1849. NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN, that His Excellency the Lieutenant-Governor has been pleased to approve of Port Victoria (heretofore known as Port Cooper) in the Province of New Munster, in the Islands of New Zealand, as a Port of Entry. By His Excellency's Command, Alfred Domett, Colonial Secretary.

- Richards, G.H. [George Henry]; Evans, F.J. [Fredrick John Owen] (1875). "Port Lyttelton or Victoria". New Zealand Pilot (Fourth ed.). London: Hydrographic Office, Admiralty. pp. 212–215. Archived from the original (Various download options available) on 12 December 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

From surveys made by H.M. ships Acheron and Pandora, Captain J. Lort Stokes, and Commander Byron Drury, 1848-55.

- "Lyttelton Harbour". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board Ngā Pou Taunaha o Aotearoa. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- McLintock, A. H., ed. (23 April 2009) [First published in 1966]. "Lyttelton". An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage / Te Manatū Taonga. Retrieved 27 September 2015.

- Hight, James; Straubel, C. R. (1957). A History of Canterbury : to 1854. I. Christchurch: Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd. p. 35.

- "Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998".

- "Ōtamahua / Quail Island Historic Area". Register of Historic Places. Heritage New Zealand. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- "Ōtamahua/Quail Island Recreation Reserve". Department of Conservation. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- "Steamer Express". New Zealand Coastal Shipping. 2003–2009. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- "Place name detail: Parson Rock". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Hutching, Chris (3 September 2018). "Blast from the past for Lyttelton dredging project?". Stuff. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "JOURNAL OF THE WEEK". Lyttelton Times. I (23). 14 June 1851. p. 5. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "JOURNAL OF THE WEEK". Lyttelton Times. I (26). 5 July 1851. p. 5. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- "Lyttelton's bad Friday". Stuff. 9 October 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Hayward, Michael (22 January 2020). "Polystyrene blocks from wrecked pontoon left to degrade for almost two decades". Stuff. Retrieved 30 January 2021.

- Andersen, Johannes C. (1927). "Map of Banks Peninsula showing principal surviving European and Maori place-names". Place-names of Banks Peninsula : a topographical history. Wellington: Govt. Printer. Retrieved 17 January 2021.

- "Place name detail: Otamahua / Quail Island". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Place name detail: Quail Island (Otamahua)". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Place name detail: Kamautaurua Island". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Place name detail: Kamautaurua (Shag Reef)". New Zealand Gazetteer. New Zealand Geographic Board. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- "Wreck at Lyttelton". Southland Times. I (12). 19 December 1862. p. 2. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Theroux, Paul (1992). The Happy Isles of Oceania. Mariner Books. p. 23.

Further reading

- Tolerton, Nick (2007). Lyttelton Icon: 100 Years of the Steam Tug Lyttelton. Christchurch, NZ: Tug Lyttelton Preservation Society. ISBN 9781877427206.

External links

- "Lyttelton Harbour c1916 (images)". Transactions of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 1916.

![]() Media related to Lyttelton Harbour at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Lyttelton Harbour at Wikimedia Commons