Partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland (Irish: críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland (now Republic of Ireland). It took place on 3 May 1921 under the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The Act intended for both home rule territories to remain within the United Kingdom and contained provisions for their eventual reunification. The smaller Northern Ireland was duly created with a devolved government and remained part of the UK. The larger Southern Ireland was not recognized by most of its citizens, who instead recognized the self-declared Irish Republic. Following the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the territory of Southern Ireland left the UK and became the Irish Free State, now the Republic of Ireland.

The territory that became Northern Ireland had a Protestant and Unionist majority who wanted to maintain ties to Britain. This was largely due to 17th century British colonization. The rest of Ireland had a Catholic and Irish nationalist majority who wanted independence. Partition took place during the Irish War of Independence (1919–21), a guerrilla conflict between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and British forces. During 1920–22, in what became Northern Ireland, partition was accompanied by violence "in defence or opposition to the new settlement". The capital Belfast saw "savage and unprecedented" communal violence, mainly between Protestant and Catholic civilians.[1] More than 500 were killed[2] and more than 10,000 became refugees, most of them Catholics.[3] In early 1922 the IRA launched a failed offensive into border areas of Northern Ireland. A Boundary Commission proposed small changes to the border in 1925, but this was not implemented.

Since partition, Irish nationalists and republicans continue to seek a reunited Ireland whereby the whole island would be an independent state, while Ulster unionists want Northern Ireland to remain part of the UK. The Unionist governments of Northern Ireland were accused of discrimination against the Irish nationalist and Catholic minority. A campaign to end discrimination was opposed by hardline Unionists who said it was a republican front.[4] This sparked the Troubles (c.1969–98), a thirty-year conflict in which more than 3,500 people were killed. Under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, the Irish and British governments agreed that the status of Northern Ireland will not change without the consent of a majority of its population.[5] In its white paper on Brexit, the British government reiterated its commitment to the Agreement. On Northern Ireland's status, it said that the government's "clearly-stated preference is to retain Northern Ireland's current constitutional position: as part of the UK, but with strong links to Ireland".[6]

Process of partition

Overview

The idea of excluding some or all of the Ulster counties from the provisions of the Home Rule Bills had been mooted at the time of the First and Second Home Rule Bills, with Joseph Chamberlain calling for Ulster to have its own government in 1892.[7][8] The unionist MP Horace Plunkett, who would later support home rule, opposed it in the 1890s because of the danger of partition.[9] Exclusion was first considered by the British cabinet in 1912, in the context of Ulster unionist opposition to the Third Home Rule Bill, which was then in preparation.[10] The Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) imported 25,000 rifles and three million rounds of ammunition from the German Empire in the Larne gun-running of April 1914, and there were fears that passing the Third Home Rule Bill could start a full-scale civil war in Ulster.[11] The Curragh incident on 20 March 1914 had already led the Government to believe that the British Army could not be relied upon to carry out its orders in Ireland.[12] The issue of partition was the main focus of discussion at the Buckingham Palace Conference held between 21 and 24 July 1914, although at the time it was believed that all nine counties of Ulster would be separated.

The Home Rule Crisis was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. Westminster passed the Home Rule Bill on 18 September 1914 and it immediately received Royal Assent, but its implementation was simultaneously postponed by a Suspensory Act until the war ended. At the time it was widely believed that the conflict would only last for a few months. Following the Easter Rising of April 1916, Westminster called the Irish Convention in an attempt to find a solution to its Irish Question; it sat in Dublin from July 1917 until March 1918, ending with a report, supported by nationalist and southern unionist members, calling for the establishment of an all-Ireland parliament consisting of two houses with special provisions for northern unionists. The report was, however, rejected by the Ulster unionist members, and Sinn Féin had not taken part in the proceedings, meaning the Convention was a failure.[13][14] Support for Irish republicanism had risen during 1917, with Sinn Féin winning four by-elections that year.[15] The Conscription Crisis of 1918 further reinforced the ascendancy of the republicans.[16]

Beginning on 21 January 1919 with the Soloheadbeg ambush, through the Irish War of Independence, Irish republicans attempted to bring about the secession of Ireland from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. Meanwhile, Irish unionists – most of whom lived in the northeast of the island – were just as determined to maintain the Union. The British Government, committed to implementing Home Rule, set up a cabinet committee under the chairmanship of southern unionist Walter Long. The Long Committee recommended the establishment of two devolved administrations, dividing the island into two territories: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. This was implemented as the Government of Ireland Act 1920.[17] The Act entered into force as a fait accompli[18] on 3 May 1921 and provided that Northern Ireland would consist of the six northeastern counties, while the remainder of the island would form Southern Ireland. It was intended that each jurisdiction would be granted home rule but remain within the United Kingdom. The government of Southern Ireland never functioned: the War of Independence continued until the two sides agreed a truce in July 1921, ending with the Anglo-Irish Treaty on 6 December 1921.

A year later, on 6 December 1922, the Irish Free State became independent of the United Kingdom in accordance with the Treaty, which was given legislative effect in the United Kingdom by the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act 1922. The new state had the status of a dominion of the British Empire.

Under the treaty, the Government of Ireland Act continued to apply in Northern Ireland for one month after the coming into being of the Free State, and Northern Ireland would continue to remain outside the Free State if the Parliament of Northern Ireland stated its desire to do so in an address to King George V within that month.[19] The wording of the treaty allowed the impression to be given that the Irish Free State temporarily included the whole island of Ireland, but legally the terms of the treaty applied only to the 26 counties, and the government of the Free State never had any powers—even in principle—in Northern Ireland.[20] On 7 December 1922 the houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland approved an address to George V, requesting that its territory not be included in the Irish Free State. This was presented to the king the following day on 8 December 1922, and then entered into effect, in accordance with the provisions of Section 12 of the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act 1922.[21] Following independence, the southern state gradually severed all remaining constitutional links with the United Kingdom and the British monarchy. The Free State was renamed "Ireland" in its new constitution of 1937, which claimed jurisdiction over the entire island. In 1949 the state was declared to be a republic, under the Republic of Ireland Act.

Government of Ireland Act

The Government of Ireland Act 1920, which came into effect on 3 May 1921, provided for separate self-governing parliaments for Northern Ireland (the six northeastern counties) and Southern Ireland (the rest of the island), thus partitioning Ireland.[22] While the parliament and governmental institutions for Northern Ireland were soon established, the election in the 26 counties returned an overwhelming majority of members giving their allegiance to Dáil Éireann and supporting the republican effort in the Irish War of Independence, thus rendering "Southern Ireland" dead in the water.

Anglo-Irish Treaty

The Irish War of Independence led to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. The treaty was given legal effect in the United Kingdom through the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922, and in Ireland by ratification by Dáil Éireann. Under the former Act, at 1pm on 6 December 1922, King George V (at a meeting of his Privy Council at Buckingham Palace)[23] signed a proclamation establishing the new Irish Free State.[24]

The treaty, and the laws which implemented it, allowed Northern Ireland to opt out of the Irish Free State.[25] Under Article 12 of the Treaty,[26] Northern Ireland could exercise its opt-out by presenting an address to the King, requesting not to be part of the Irish Free State. Once the treaty was ratified, the Houses of Parliament of Northern Ireland had one month (dubbed the Ulster month) to exercise this opt-out during which time the provisions of the Government of Ireland Act continued to apply in Northern Ireland.

Northern Ireland opts out

The treaty "went through the motions of including Northern Ireland within the Irish Free State while offering it the provision to opt out".[27] It was certain that Northern Ireland would exercise its opt out. The Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Sir James Craig, speaking in the House of Commons of Northern Ireland in October 1922, said that "when the 6th of December is passed the month begins in which we will have to make the choice either to vote out or remain within the Free State." He said it was important that that choice be made as soon as possible after 6 December 1922 "in order that it may not go forth to the world that we had the slightest hesitation."[28] On the following day, 7 December 1922, the Parliament of Northern Ireland resolved to make the following address to the King so as to opt out of the Irish Free State:[29]

MOST GRACIOUS SOVEREIGN, We, your Majesty's most dutiful and loyal subjects, the Senators and Commons of Northern Ireland in Parliament assembled, having learnt of the passing of the Irish Free State Constitution Act, 1922, being the Act of Parliament for the ratification of the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, do, by this humble Address, pray your Majesty that the powers of the Parliament and Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland.

Discussion in the Parliament of the address was short. Craig left for London with the memorial embodying the address on the night boat that evening, 7 December 1922. King George V received it the following day, The Times reporting:[30]

YORK COTTAGE, SANDRINGHAM, DEC. 8. The Earl of Cromer (Lord Chamberlain) was received in audience by The King this evening and presented an Address from the Houses of Parliament of Northern Ireland, to which His Majesty was graciously pleased to make reply.

If the Houses of Parliament of Northern Ireland had not made such a declaration, under Article 14 of the Treaty, Northern Ireland, its Parliament and government would have continued in being but the Oireachtas would have had jurisdiction to legislate for Northern Ireland in matters not delegated to Northern Ireland under the Government of Ireland Act. This never came to pass. On 13 December 1922, Craig addressed the Parliament of Northern Ireland, informing them that the King had responded to the Parliament's address as follows:[31]

I have received the Address presented to me by both Houses of the Parliament of Northern Ireland in pursuance of Article 12 of the Articles of Agreement set forth in the Schedule to the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act, 1922, and of Section 5 of the Irish Free State Constitution Act, 1922, and I have caused my Ministers and the Irish Free State Government to be so informed.

Background

1886–1914

After the 1885 UK general election the nationalist Irish Parliamentary Party held the balance of power in the House of Commons, and entered into an alliance with the Liberals. Its leader, Charles Stewart Parnell convinced William Gladstone to introduce the First Irish Home Rule Bill in 1886. An Irish Unionist Party was immediately founded; this organised demonstrations in Belfast against the Bill, fearing that separation from Great Britain would bring industrial decline and religious persecution of Protestants by a Roman Catholic-dominated Irish government. English Conservative politician Lord Randolph Churchill proclaimed: "the Orange card is the one to play", which was later expressed in the popular slogan, "Home Rule means Rome Rule".[32]

In many rural parts of Ireland, a "Land War" (1879–1890) was under way, supported by many nationalists, that had led to sporadic violence. The Representation of the People Act 1884 had enlarged the popular franchise, and many property-owners, particularly unionists, were concerned that their interests would be reduced by a new Irish political class.

Although the bill was defeated, Gladstone remained undaunted, and introduced a Second Irish Home Rule Bill in 1892 that passed the Commons. Accompanied by similar mass unionist protests, Joseph Chamberlain called for a (separate) provincial government for Ulster even before the bill was rejected by the House of Lords. The seriousness of the situation was highlighted when Irish unionists throughout the island assembled at conventions in Dublin and Belfast to oppose both the Bill and the proposed partition.[8]

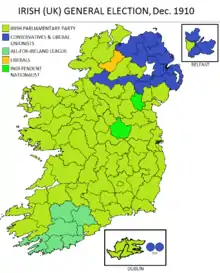

When, in 1910, the Irish Party again held the balance of power in the Commons, H. H. Asquith introduced a Third Home Rule Bill in 1912. The unionists adopted the positions they had demonstrated in 1886 and 1893. With the veto of the Lords removed by the Parliament Act 1911, and the clear prospect of Home Rule passing into law, Ulster loyalists established the Ulster Volunteers in 1912 to oppose enactment of the Bill, as well as what they called its "Coercion of Ulster", and threatened to establish a Provisional Ulster Government. In 1913, the Ulster Volunteers were re-organised into an Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

While the Home Rule Bill was still being debated, on 20 March 1914, many British Army officers threatened to resign in what became known as the "Curragh Incident" (also known, incorrectly, as "The Curragh Mutiny"), rather than be mobilised to enforce the Act on Ulster. This meant that the British government could legislate for Home Rule but could not be sure of making it a reality on the ground. This led on to an amending Bill that would exclude Ulster for an indefinite period, and the new fear of a civil war (between unionists, and nationalists, who had set up the Irish Volunteers in response to the UVF's formation) in Ireland led to the Buckingham Palace Conference in July 1914.

1914–1922

The Home Rule Act reached the statute book with Royal Assent in September 1914 (although the amending Bill was abandoned) but, because of the First World War, its commencement was suspended for one year or for the duration of what was expected to be a short war. It intended to grant self-government to the entire island of Ireland as a single jurisdiction under Dublin administration, but the final version as enacted in 1914 included an amendment clause for six Ulster counties to remain under London administration for a proposed trial period of six years, yet to be finally agreed. This was belatedly conceded by John Redmond, leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party, as a compromise in order to pacify Ulster unionists and avoid civil war.

In 1917–18, the Irish Convention attempted to resolve what sort of Home Rule would follow the First World War. Unionist and nationalist politicians met in a common forum for the last time before partition. The Ulster unionists preferred to remain within the United Kingdom; the nationalist Home Rule parties and the Southern Unionists argued against partition. The growing Sinn Féin party refused to attend.

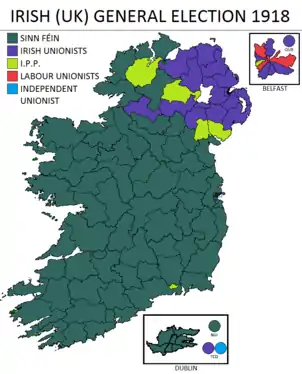

Soon after the end of the war, Sinn Féin won the overwhelming majority of the Irish parliamentary seats in the UK general election of 1918, and in January 1919 the Sinn Féin members declared unilaterally an independent (all-island) Irish Republic. Unionists, however, won a majority of seats in four of the nine counties of Ulster and affirmed their continuing loyalty to the United Kingdom. Following the Paris Peace Conference, in September 1919 David Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, tasked the Long Committee with implementing Britain's commitment to introduce Home Rule, which was based on the policy of Walter Long, and some findings of the Irish Convention. The result was to be two home-rule Irish jurisdictions, and in November 1920 the Government of Ireland Act 1920 was enacted. As a result of this, in April 1921 the island was partitioned into Southern and Northern Ireland.

On 5 May 1921, the Ulster Unionist leader Sir James Craig met with the President of Sinn Féin, Éamon de Valera, in secret near Dublin. Each restated his position and nothing new was agreed. On 10 May De Valera told the Dáil that the meeting "... was of no significance".[33] In June that year, shortly before the truce that ended the Anglo-Irish War, David Lloyd George invited the Republic's President de Valera to talks in London on an equal footing with the new Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, James Craig, which de Valera attended. De Valera's policy in the ensuing negotiations was that the future of Ulster was an Irish-British matter to be resolved between two sovereign states, and that Craig should not attend.[34] After the truce came into effect on 11 July, Lloyd George made it clear to de Valera, 'that the achievement of a republic through negotiation was impossible'.[35]

On 20 July, Lloyd George further declared to de Valera that:

The form in which the settlement is to take effect will depend upon Ireland herself. It must allow for full recognition of the existing powers and privileges of the Parliament of Northern Ireland, which cannot be abrogated except by their own consent. For their part, the British Government entertain an earnest hope that the necessity of harmonious co-operation amongst Irishmen of all classes and creeds will be recognised throughout Ireland, and they will welcome the day when by those means unity is achieved. But no such common action can be secured by force.[36]

In reply, de Valera wrote

We most earnestly desire to help in bringing about a lasting peace between the peoples of these two islands, but see no avenue by which it can be reached if you deny Ireland's essential unity and set aside the principle of national self-determination.[36]

The treaty as ratified in December 1921 and January 1922 allowed for a re-drawing of the mutual border by a Boundary Commission. Northern Ireland was deemed to be a part of the Irish Free State, whenever it became established, but its parliament would be allowed to vote to secede within a month, the so-called "Ulster month".

Unionist objections to Anglo-Irish Treaty

Sir James Craig, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland objected to aspects of the Anglo-Irish Treaty. In a letter to Austen Chamberlain dated 14 December 1921, he stated:

We protest against the declared intention of your government to place Northern Ireland automatically in the Irish Free State. Not only is this opposed to your pledge in our agreed statement of November 25th, but it is also antagonistic to the general principles of the Empire regarding her people's liberties. It is true that Ulster is given the right to contract out, but she can only do so after automatic inclusion in the Irish Free State. It is a complete reversal of the British Cabinet's own policy as declared in the King's speech at the opening of the Northern parliament and in the Premier's published correspondence with de Valera. That policy was that Ulster should remain out until she chose of her own free will to enter an All-Ireland parliament. Neither explanation nor justification for this astounding change has been attempted. We can only conjecture that it is a surrender to the claims of Sinn Fein that her delegates must be recognised as the representatives of the whole of Ireland a claim which we cannot for a moment admit...[With regard to references to Belfast Lough in the Anglo-Irish Treaty, Craig continued]...What right has the Sinn Fein to be a party to an agreement concerning the defences of Belfast Lough, which touches only the loyal counties of Antrim and Down.... The principles of the 1920 Act have been completely violated, the Irish Free State being relieved of many of her responsibilities towards the Empire. The Sinn Fein receives a financial advantage that will relieve her considerably from the burden borne by Ulster and other parts of the Kingdom. Ulster can obtain such concessions only by first becoming subordinate to the Sinn Fein.... In spite of the inducements held out to Ulster, we are convinced that it is not in the best interests of Britain or the Empire that Ulster should become subordinate to the Sinn Fein. We are glad to think that our decision will obviate the necessity of mutilating the Union Jack.[37][38]

Nationalist objections to the Anglo-Irish Treaty

Michael Collins had negotiated the treaty and had it approved by the cabinet, the Dáil (on 7 January 1922 by 64–57), and by the people in national elections. Regardless of this, it was unacceptable to Éamon de Valera, who led the Irish Civil War to stop it. Collins was primarily responsible for drafting the constitution of the new Irish Free State, based on a commitment to democracy and rule by the majority.[39]

De Valera's minority refused to be bound by the result. Collins now became the dominant figure in Irish politics, leaving de Valera on the outside. The main dispute centred on the proposed status as a dominion (as represented by the Oath of Allegiance and Fidelity) for Southern Ireland, rather than as an independent all-Ireland republic, but continuing partition was a significant matter for Ulstermen like Seán MacEntee, who spoke strongly against partition or re-partition of any kind.[40] The pro-treaty side argued that the proposed Boundary Commission would satisfy the greatest number on each side of the eventual border, and felt that the Council of Ireland (as envisaged by the 1920 Home Rule Act) would lead to unity by consent over a longer period.

De Valera had drafted his own preferred text of the treaty in December 1921, known as "Document No. 2". An "Addendum North East Ulster" indicates his acceptance of the 1920 partition for the time being, and of the rest of Treaty text as signed in regard to Northern Ireland:

That whilst refusing to admit the right of any part of Ireland to be excluded from the supreme authority of the Parliament of Ireland, or that the relations between the Parliament of Ireland and any subordinate legislature in Ireland can be a matter for treaty with a Government outside Ireland, nevertheless, in sincere regard for internal peace, and in order to make manifest our desire not to bring force or coercion to bear upon any substantial part of the province of Ulster, whose inhabitants may now be unwilling to accept the national authority, we are prepared to grant to that portion of Ulster which is defined as Northern Ireland in the British Government of Ireland Act of 1920, privileges and safeguards not less substantial than those provided for in the 'Articles of Agreement for a Treaty' between Great Britain and Ireland signed in London on 6 December 1921.[41]

Details of the partition

Debate on Ulster Month

As described above, under the treaty it was provided that Northern Ireland would have a month – the "Ulster Month" – during which its Houses of Parliament could opt out of the Irish Free State. The Treaty was ambiguous on whether the month should run from the date the Anglo-Irish Treaty was ratified (in March 1922 via the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act) or the date that the Constitution of the Irish Free State was approved and the Free State established (6 December 1922).[42] This question was the subject of some debate.

When the Irish Free State (Agreement) Bill was being debated on 21 March 1922, amendments were proposed which would have provided that the Ulster Month would run from the passing of the Irish Free State (Agreement) Act and not the Act that would establish the Irish Free State. Essentially, those who put down the amendments wished to bring forward the month during which Northern Ireland could exercise its right to opt out of the Irish Free State. They justified this view on the basis that if Northern Ireland could exercise its option to opt out at an earlier date, this would help to settle any state of anxiety or trouble on the new Irish border. Speaking in the House of Lords, the Marquess of Salisbury argued:[43]

The disorder [in Northern Ireland] is extreme. Surely the Government will not refuse to make a concession which will do something... to mitigate the feeling of irritation which exists on the Ulster side of the border.... [U]pon the passage of the Bill into law Ulster will be, technically, part of the Free State. No doubt the Free State will not be allowed, under the provisions of the Act, to exercise authority in Ulster; but, technically, Ulster will be part of the Free State.... Nothing will do more to intensify the feeling in Ulster than that she should be placed, even temporarily, under the Free State which she abominates. Besides that there is the unrest in Ulster as a whole and the special unrest in the area which is to be the subject of delimitation.... I need not remind your Lordships that the area in doubt, although according to His Majesty's Government it is small, is, in the opinion of the leaders of the Free State, a very large area.

The British Government took the view that the Ulster Month should run from the date the Irish Free State was established and not beforehand, Viscount Peel for the Government remarking:[42]

His Majesty's Government did not want to assume that it was certain that on the first opportunity Ulster would contract out. They did not wish to say that Ulster should have no opportunity of looking at entire Constitution of the Free State after it had been drawn up before she must decide whether she would or would not contract out.

Viscount Peel continued by saying the government desired that there should be no ambiguity and would to add a proviso to the Irish Free State (Agreement) Bill providing that the Ulster Month should run from the passing of the Act establishing the Irish Free State. He further explained that the members of the Parliament of Southern Ireland had agreed to put that interpretation upon it. He noted that he had received from Arthur Griffith the following letter dated 20 March 1922:[42]

While it is held by the Irish plenipotentiaries and the Ministers of the Provisional Government that in the strict reading and interpretation of the Treaty the month in which North-East Ulster should exercise its option should run as from the date of the passing of the Bill [ratifying the Anglo-Irish Treaty rather than establishing the Irish Free State], they recognize that strong arguments might be made for the advisability of allowing North-East Ulster to consider the Constitution of the Irish Free State before exercising its option and they are willing to waive their interpretation, and agree that the [Ulster] month should run as from the date of the formal adoption of the Constitution [of the Irish Free State].

Lord Birkenhead remarked in the Lords debate:[43]

I should have thought, however strongly one may have embraced the cause of Ulster, that one would have resented it as an intolerable grievance if, before finally and irrevocably withdrawing from the Constitution, she was unable to see the Constitution from which she was withdrawing.

On 7 December 1922, the day after the establishment of the Irish Free State, the House of Commons of Northern Ireland heard an address by Sir James Craig to King George V requesting: "...that the powers of the Parliament and Government of the Irish Free State shall no longer extend to Northern Ireland". No division or vote was requested on the address, which was described as the Constitution Act and was then approved by the Senate of Northern Ireland.[44]

Customs posts established

While the Irish Free State was established at the end of 1922, the Boundary Commission contemplated by the Treaty was not to meet until 1924. Things did not remain static during that gap. In April 1923, just four months after independence, the Irish Free State established customs barriers on the border. This was a significant step in consolidating the border:[45]

The passage of time was ensuring that the Border was acquiring inertia. While its final position was sidelined, its functional dimension was actually being underscored by the Free State with its imposition of a customs barrier from April 1923.

Boundary Commission 1922–25

The Anglo-Irish Treaty contained a provision that would establish a boundary commission, which could adjust the border as drawn up in 1920. Most leaders in the Free State, both pro- and anti-treaty, assumed that the commission would award largely nationalist areas such as County Fermanagh, County Tyrone, South Londonderry, South Armagh and South Down, and the City of Derry to the Free State, and that the remnant of Northern Ireland would not be economically viable and would eventually opt for union with the rest of the island as well. In the event, the commission's decision was made for it by the inter-governmental agreement of 3 December 1925 that was published later that day by Stanley Baldwin.[46] As a result, the Commission's report was not published; the detailed article explains the factors involved.

The Dáil voted to approve the agreement, by a supplementary act, on 10 December 1925 by a vote of 71 to 20.[47]

Background

The division of territorial waters as between Northern Ireland and the Irish Free State was to be a lingering matter of controversy for a number of years. Section 1(2) of the Government of Ireland Act 1920 defined the respective territories of Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland as follows:[48]

...Northern Ireland shall consist of the parliamentary counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Derry and Tyrone, and the parliamentary boroughs of Belfast and Derry, and Southern Ireland shall consist of so much of Ireland as is not comprised within the said parliamentary counties and boroughs.

At the time of that act, both Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland were to remain parts of the United Kingdom. Perhaps because of this, the Act did not explicitly address the position of territorial waters, although section 11(4) provided that neither Southern Ireland nor Northern Ireland would have any competence to make laws in respect of "lighthouses, buoys, or beacons (except so far as they can consistently with any general Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom be constructed or maintained by a local harbour authority)".

When the territory that was Southern Ireland became a separate self-governing dominion outside the United Kingdom known as the Irish Free State, the status of the territorial waters naturally took on a significance it had not had before. The Northern Ireland Unionists were conscious of this matter from an early stage. They were keen to put it beyond doubt that the territorial waters around Northern Ireland would not belong to the Irish Free State. In this regard, Sir James Craig, the Prime Minister of Northern Ireland put the following question in the British House of Commons on 27 November 1922 (the month before the establishment of the Irish Free State):[49]

Another important matter on which I should like a statement of the Government's intentions, is with regard to the territorial waters surrounding Ulster. Under the Act of 1920, the areas handed over to the Governments of Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland respectively, were defined as the six Parliamentary counties of Northern Ireland and the twenty-six Parliamentary counties of Southern Ireland. I understand there is considerable doubt in the minds of lawyers and others as to whether these Parliamentary counties carry with them the ordinary territorial waters, extending three miles out from the shore. It has been asserted in some quarters that the Parliamentary counties only extend to low water mark. That has been exercising the minds of a good many people in Ulster, and I shall be glad if the Government in due course will inform the House what is their opinion on the subject and what steps they are taking to make it clear.... Am I to understand that the Law Officers have actually considered this question, and that they have given a decision in favour of the theory that the territorial waters go with the counties that were included in the six counties of Northern Ireland?

In response the Attorney General, Sir Douglas Hogg said that "I have considered the question, and I have given an opinion that that is so [i.e. the territorial waters do go with the counties]".

Dispute arises

A particular dispute arose between the Government of the Irish Free State of the one part and the Northern Ireland and UK Governments of the other part over territorial waters in Lough Foyle.[50] Lough Foyle lies between County Londonderry in Northern Ireland and County Donegal in the then Irish Free State. A court case in the Free State in 1923 relating to fishing rights in Lough Foyle held that the Free State's territorial waters ran right up to the shore of County Londonderry.[50] In 1925, the Chief Justice of the Irish Free State, Hugh Kennedy, advised the President of the Executive Council of the Irish Free State, W. T. Cosgrave, as follows:

- A Uachtaráin, A Chara dhílis,

- I saw in some paper the other day some reference to a claim by the Northerners that they are entitled to the whole of Lough Foyle. It occurred to me that I should drop you a line lest the question of territorial jurisdiction as regards water might be lost sight of. You will remember the point that was made that Northern Ireland consists of certain parliamentary counties and that the Free State consists of the rest of Ireland, so defined by the Government of Ireland Act, 1920; and you will remember that we have always contended that this definition gave us the whole sea shore surrounding the country, together with loughs upon which both Northern Ireland and ourselves abutted.

- As far as I could make out — but I never could get anything definite upon it — this view was held in London in the early period of 1922, and was taken, I believe, by the first Law Officers who dealt with our business. Subsequently I was told, but only by hints, that later law officers had given a definite opinion the other way. I know that the Parliamentary Draftsmen were very shaky on the question and nervous about it until they got the later opinion.

- Should it not be made clear at the Boundary Commission that we claim to have already in the Free State the whole of Ireland except the territory represented by the parliamentary areas of the Six Counties? The attempt to capture Lough Foyle would be very serious.

- Mise do chara,

- (HUGH KENNEDY) Chief Justice[51]

In 1927, illegal (as viewed by the Northern administration) fishing on Lough Foyle had become so grave that Northern Ireland Prime Minister, James Craig entered into correspondence with his Free State counterpart, W. T. Cosgrave. Craig indicated to Cosgrave that he proposed to introduce a Bill giving the Royal Ulster Constabulary powers to stop and search vessels on Lough Foyle. Cosgrave asserted all of Lough Foyle was Free State territory and that as such a Bill of that nature would be rejected by the Free State and its introduction would create "a very serious situation".[50] Cosgrave then raised the matter with the British government.

In 1936, the Minister for External Affairs was asked in Dáil Éireann if he intended to take any steps to safeguard and maintain the rights to fishing in certain parts of Lough Foyle, claimed by and hitherto enjoyed by Free State nationals. The Vice-President (for the Minister for External Affairs), responding, noted that there had been correspondence between the two Governments in recent years. He summarised the position as currently being that:

The matter, therefore, now stands as follows. The Government of Saorstát Éireann are still willing to make temporary administrative arrangements for the preservation of order on the waters of Lough Foyle pending the settlement of the fishery dispute and without prejudice to the general question of jurisdiction. But we decline to accept either of the conditions which the British Government seek to impose as a condition precedent to those arrangements. We decline, that is to say, either (1) to give any undertaking that we will submit the international dispute as to our jurisdiction in the Lough Foyle area to a British Commonwealth Tribunal or (2) to make any agreement with regard to the fishery dispute itself which would prejudice the issue in that dispute or which would purport to remove the legal right of any citizen of Saorstát Éireann to test the claim of the Irish Society or their lessees in the courts of this country.[52]

The Minister was criticised by Opposition politicians for his government's overall indecision on whether the Irish Free State should remain part of the British Commonwealth, a spokesman claiming this was why the Government had such difficulty with the British Government's first pre-condition.[52]

Second World War

With the fall of France in 1940, the British Admiralty ordered convoys to be re-routed through the north-western approaches which would take them around the north coast and through the North Channel to the Irish Sea. However, escorting those convoys raised a problem: it became imperative to establish an escort base as far west in the United Kingdom as possible. There was one obvious location: Lough Foyle. However, it remained unclear where the border was between the UK and Ireland in Lough Foyle. On 31 August 1940, Sir John Maffey, the UK's representative to the Irish government, wrote to the Dominions Office in London that:[53]

use by Admiralty of Lough Foyle should from now on be constant but for the present on limited scale so that use may be established quietly if possible. My inclination is to make no communication on the subject to the Eire Government, to wait on events and to let them know when and if use on large scale is intended. So far as naval use is concerned we appear to have [a] good case.

In September 1940 Maffey approached the Irish External Affairs Secretary, Joseph Walshe, to inform him ‘of the intended increase of light naval craft’ in Lough Foyle. The Royal Navy increased its use of Lough Foyle in the early months of 1941.[53] The Royal Navy remained concerned that there might be a challenge to its use of the Foyle on the grounds that ships navigating the river to Lisahally and Londonderry might be infringing Irish neutrality. If the border followed the median line of Lough Foyle then the channel might be in Irish waters as it "lies near to the Eire shore". In mid-November 1941, legal opinions of solicitors to The Honourable The Irish Society were presented to the Royal Navy.[53] The Hon. The Irish Society's view was that the whole of Lough Foyle was part of County Londonderry and accordingly the border could not be that of the median line of Lough Foyle. The Royal Navy continued to use its new base on the Foyle until 1970.[53]

British Cabinet consideration in 1949

At a British Cabinet meeting on 22 November 1948 it was decided that a working party be established to "[consider] what consequential action may have to be taken by the United Kingdom Government as a result of Éire's ceasing to be a member of the Commonwealth".[54] The Working Party was chaired by the Cabinet Secretary, Norman Brook. Its report dated 1 January 1949 was presented by Prime Minister Clement Attlee to the Cabinet on 7 January 1949. The following is para 23 of the Working Party's report (which speaks for itself):[54]

Boundary of Northern Ireland – The Government of Northern Ireland ask that the question of their territorial jurisdiction should be put beyond doubt. In 1920 Northern Ireland was defined as the six Parliamentary Counties of Antrim, Armagh, Down, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Tyrone, and the two Parliamentary Boroughs of Belfast and Londonderry, and in 1922 a Commission was appointed to delimit the boundary more precisely. The Commission activities proved abortive. The boundary in Lough Foyle and the River Foyle and in Carlingford Lough is open to dispute. Article 2 of the Eire Constitution of 1937 provided that the national territory included the whole of the territorial seas of Ireland, and Eire spokesmen have repeatedly laid claim to the territorial waters round Northern Ireland. The Government of Northern Ireland claim that the County of Londonderry includes the whole of Lough Foyle, which lies between the Counties of Londonderry and Donegal, and the whole of the River Foyle in that stretch of it which separates the Counties of Tyrone and Donegal. We do not believe that this claim could be sustained, and to raise the boundary issue would jeopardise the access to Londonderry, since the navigable channel in Lough Foyle hugs the Donegal shore. There is a similar risk in raising the boundary question in Carlingford Lough, where the navigable channel giving access to Newry is partly on the Northern Ireland side and partly on the Eire side of the Lough. There is no substance in the Eire claim to the Northern Ireland territorial waters, but the Eire Government have never taken any steps to assert their alleged rights in these waters, nor is it clear what steps they could take to do so. We accordingly recommend that no attempt should be made by the United Kingdom Government, whether by legislation or declaration, to define the boundary of Northern Ireland. Our main reason for this recommendation is that any such attempt might seriously prejudice our interests in retaining unrestricted access to Londonderry in peace and war.

Dispute simmers

The division of the territorial waters continued to be a matter disputed between the two Governments. On 29 February 1972, during a Dáil debate about internment in Northern Ireland, deputy Richie Ryan questioned the legitimacy of anchoring the Maidstone prison ship in Belfast Lough to accommodate internees. A good summary of the Irish position on the territorial waters issue was given by then Taoiseach, Mr. Jack Lynch:

...[W]e claim that the territorial waters around the whole island of Ireland are ours and our claim to the territorial waters around Northern Ireland is based on the Government of Ireland Act of 1920. This Act is so referred to in the 1921 Treaty that the Northern Ireland which withdrew from the Irish Free State is identical with the Northern Ireland defined in the Government of Ireland Act, 1920, and defined as consisting of named counties and boroughs. It is, I think, common case between us that in English law the counties do not include adjacent territorial waters and, therefore, according to our claim these territorial waters were retained by the Irish Free State.[55]

Other incidents have occurred from time to time in the disputed waters, and they have been discussed in Dáil Éireann occasionally.[56][57][58]

Current status

The territorial dispute between Ireland and the United Kingdom concerning Lough Foyle (and similarly Carlingford Lough) is still not settled. As recently as 2005, when asked to list those areas of EU member states where border definition is in dispute, a British Government minister responding for the Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs stated:

Border definition (ie the demarcation of borders between two internationally recognized sovereign states with an adjoining territorial or maritime border) is politically disputed [between] Ireland [and the] UK (Lough Foyle, Carlingford Lough—quiescent)[59]

In 2009, the territorial dispute concerning Lough Foyle was raised in a meeting of the Northern Ireland Assembly's Committee for Enterprise Trade and Investment. The committee was meeting to discuss Project Kelvin, a project involving the construction of a fiber optic telecommunications cable between North America and Northern Ireland. Mr Derek Bullock, an executive from Hibernia Atlantic Limited, the cable-laying company leading the project's implementation had to explain to the committee why the cable landing station was going to be located at Coleraine rather than Derry City as initially indicated.[60] He explained that one of the reasons it had been decided not to locate the cable landing station in Lough Foyle was because:

We cannot bring a cable into Lough Foyle, because the border line under the sea there is actually disputed.... Lough Foyle is a disputed border region, and, as I said, we cannot put submarine cables near disputed border regions.[60]

The Foreign and Commonwealth Office underlined its view on 2 June 2009 that all of Lough Foyle is in the United Kingdom, a spokesperson stating:

The UK position is that the whole of Lough Foyle is within the UK. We recognise that the Irish Government does not accept this position.... There are no negotiations currently in progress on this issue. The regulation of activities in the Lough is now the responsibility of the Loughs Agency, a cross-border body established under the Belfast Agreement of 1998.[61]

A corresponding statement was made by Conor Lenihan, then an Irish Government Minister:

[t]here has never been any formal agreement between Ireland and the United Kingdom on the delimitation of a territorial water boundary between the two states. In the context of the Good Friday Agreement, a decision was taken to co-operate on foreshore and other issues that arise in the management of the lough from conservation and other points of view. One of the issues is that the median channel in Carlingford is the navigation channel whereas... the navigation channel in Lough Foyle hugs the southern side, which makes it rather more difficult to manage or to negotiate an agreement as to where the territorial waters actually lie. There is no agreement between the two Governments on where the boundary lies, which is a problem that has bedevilled the situation for some time.

The two governments signed a Memorandum of Understanding[62] pertaining to the promotion of offshore renewable energy development in the seas adjacent to the Lough Foyle (and Carlingford Lough) in 2011. This was signed without prejudice to outstanding issues concerning sovereignty.

Partition and sport

Following partition some social and sporting bodies divided but others did not. Today in Ireland many sports, such as boxing, Gaelic football, hurling, cricket and rugby union, are organised on an all-island basis, with a single team representing Ireland in international competitions. Other sports, such as association football (soccer), have separate organising bodies in Northern Ireland (Irish Football Association) and the Republic of Ireland (Football Association of Ireland). At the Olympics, a person from Northern Ireland can choose to represent either the Republic of Ireland team (which competes as "Ireland") or United Kingdom team (which competes as "Great Britain"). Selection usually depends on whether his or her sport is organised on an all-Ireland, a Northern Ireland, or a UK basis. Sports organised on an all-Ireland basis are affiliated to the Republic of Ireland's Olympic association, whereas those organised on a Northern Ireland or UK basis are generally affiliated to the UK's Olympic association.

Partition and rail transport

Rail transport in Ireland was seriously affected by partition. The railway network on either side of the border relied on cross-border routes, and eventually a large section of the Irish railway route network was shut down. Today only the cross-border route from Dublin to Belfast remains, and counties Cavan, Donegal, Fermanagh, Monaghan and Tyrone have no rail services.

After partition

Constitution of Ireland 1937

De Valera came to power in Dublin in 1932, and drafted a new Constitution of Ireland which in 1937 was adopted by plebiscite in the Irish Free State. Its articles 2 and 3 defined the 'national territory' as: "the whole island of Ireland, its islands and the territorial seas". The state was named 'Ireland' (in English) and 'Éire' (in Irish); a United Kingdom Act of 1938 described the state as "Eire".

To unionists in Northern Ireland, the 1937 constitution made the ending of partition even less desirable than before. Most were Protestants, but article 44 recognised the 'special position' of the Roman Catholic Church. Further, the preamble referred to: "...our Divine Lord, Jesus Christ, Who sustained our fathers through centuries of trial, Gratefully remembering their heroic and unremitting struggle to regain the rightful independence of our Nation,"; this was an independence that unionists had opposed, and seemed to imply in an insulting fashion that Jesus had sustained only the Irish independence movement, and never the unionist cause. All spoke English, but article 8 stipulated that the new 'national language' and 'first official language' was to be Irish, with English as the 'second official language'.

The irrendentist texts in Articles 2 and 3 were deleted by the Nineteenth Amendment in 1998, as part of the Belfast Agreement.

Anti-partition groups

Nationalists also established a number of anti-partition groups campaigning against the border, starting with de Valera's National League of the North (1928) which was renamed the Irish Union Association and then the Anti-Partition League in 1938. These were followed by the Northern Council for Unity, the Irish Anti-Partition League, the All Ireland Anti-Partition League and finally National Unity (Ireland) in 1964. None achieved an electoral majority and they were prone to divisions.

In the United States the 1947 Irish Race Convention arranged for a vote in the US Congress whereby Marshall Aid for Britain would be conditional on the end of partition. The vote was lost by 206 votes to 139, with 83 abstaining.

British offer of unity in 1940

During the Second World War, after the Fall of France, Britain made a qualified offer of Irish unity in June 1940, without reference to those living in Northern Ireland. On their rejection, neither the London or Dublin governments publicised the matter.

Ireland would have joined the allies against Germany by allowing British ships to use its ports, arresting Germans and Italians, setting up a joint defence council and allowing overflights.

In return, arms would have been provided to Ireland and British forces would cooperate on a German invasion. London would have declared that it accepted 'the principle of a United Ireland' in the form of an undertaking 'that the Union is to become at an early date an accomplished fact from which there shall be no turning back.'[63]

Clause ii of the offer promised a joint body to work out the practical and constitutional details, 'the purpose of the work being to establish at as early a date as possible the whole machinery of government of the Union'.

The proposals were first published in 1970 in a biography of de Valera.[64]

1945–1973

In May 1949 the Taoiseach John A. Costello introduced a motion in the Dáil strongly against the terms of the UK's Ireland Act 1949 that confirmed partition for as long as a majority of the electorate in Northern Ireland wanted it, styled in Dublin as the "Unionist Veto".[65] This was a change from his position supporting the Boundary Commission back in 1925, when he was a legal adviser to the Irish government. A possible cause was that his coalition government was supported by the strongly republican Clann na Poblachta. From this point on all the political parties in the Republic were formally in favour of ending partition, regardless of the opinion of the electorate in Northern Ireland.

The new republic could not, and in any event did not wish to, remain in the Commonwealth; and it chose not to join NATO when that was founded in 1949. These decisions broadened the effects of partition, but were in line with the evolving policy of Irish neutrality.

Congressman John E. Fogarty was the main mover of the Fogarty Resolution on 29 March 1950. This proposed suspending Marshall Plan Foreign Aid to the UK, as Northern Ireland was costing Britain $150,000,000 annually, and therefore American financial support for Britain was prolonging the partition of Ireland. Whenever partition was ended, Marshall Aid would restart. On 27 September 1951, Fogarty's resolution was defeated in Congress by 206 votes to 139, with 83 abstaining – a factor that swung some votes against his motion was that Ireland had remained neutral during World War II.[66]

The Taoiseach Seán Lemass visited Northern Ireland in secrecy in 1966, leading to a return visit to Dublin by Terence O'Neill; it had taken four decades to achieve such a simple meeting. The impact was further reduced when both countries joined the European Communities in 1973. After the onset of the Troubles (1969–98), a 1973 referendum showed that a majority of the electorate in Northern Ireland did want to continue the link to Britain as expected, but the referendum was boycotted by Nationalist voters.

Possibility of British withdrawal in 1974

Following the start of the Troubles in Northern Ireland in 1969, the Sunningdale Agreement was signed by the Irish and British governments in 1973. This collapsed in May 1974 due to the Ulster Workers' Council strike, and the new British Prime Minister Harold Wilson considered a rapid withdrawal of the British Army and administration from Northern Ireland in 1974–75 as a serious policy option. The relevant cabinet notes remained secret until 2005.[67]

The effect of such a withdrawal was considered by Garret FitzGerald, the then Minister for Foreign Affairs in Dublin, and recalled in his 2006 essay.[68] The Irish cabinet concluded that such a withdrawal would lead to widescale civil war and a greater loss of life, which the Irish Army of 12,500 men could do little to prevent.

The Good Friday Agreement

The Good Friday Agreement in 1998, was ratified by two referendums in both parts of Ireland, including an acceptance by the Republic that its claim to Northern Ireland would only be achieved by peaceful means. This was an important part of the Northern Ireland peace process that had been under way since 1993. The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was repealed in the UK by the Northern Ireland Act 1998 as a result of the Agreement, and in Ireland by the Statute Law Revision Act 2007.

See also

Notes

- Lynch, Robert. The Partition of Ireland: 1918–1925. Cambridge University Press, 2019. p.11, 100–101

- Lynch (2019), p.99

- Lynch (2019), pp.171–176

- Maney, Gregory. "The Paradox of Reform: The Civil Rights Movement in Northern Ireland", in Nonviolent Conflict and Civil Resistance. Emerald Group Publishing, 2012. p.15

- Smith, Evan (20 July 2016). "Brexit and the history of policing the Irish border". History & Policy. History & Policy. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- HM Government The United Kingdom's exit from and new partnership with the European Union; Cm 9417, February 2017

- Bardon, Jonathan (1992). A History of Ulster. Blackstaff Press. p. 402. ISBN 0856404985.

- Maume, Patrick (1999). The long Gestation: Irish Nationalist Life 1891–1918. Gill and Macmillan. p. 10. ISBN 0-7171-2744-3.

- King, Carla (2000). "Defenders of the Union: Sir Horace Plunkett". In Boyce, D. George; O'Day, Alan (eds.). Defenders of the Union: A Survey of British and Irish Unionism Since 1801. Routledge. p. 153. ISBN 1134687435.

- Fanning, Ronan (2013). Fatal Path: British Government and Irish Revolution 1910–1922. London: Faber and Faber. p. 63. ISBN 978-0571297412. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- "The Home Rule Crisis 1910 - 1914". Historyhome.co.uk. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Holmes, Richard (2004). The Little Field Marshal: A Life of Sir John French. Weidenfeld & Nicolson. p. 168. ISBN 0-297-84614-0.

- Lyons, F.S.L. (1996). "The new nationalism, 1916-18". In Vaughn, W.E. (ed.). A New History of Ireland: Ireland under the Union, II, 1870-1921. Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 9780198217510. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Hachey, Thomas E. (2010). The Irish Experience Since 1800: A Concise History. M.E. Sharpe. p. 133. ISBN 9780765628435. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Coleman, Marie (2013). The Irish Revolution, 1916-1923. Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-1317801474. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Coleman (2013), p. 39

- Jackson, Alvin (2010). Ireland 1798-1998: War, Peace and Beyond (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 239. ISBN 978-1444324150. Retrieved 18 April 2017.

- Garvin, Tom: The Evolution of Irish Nationalist Politics : p.143 Elections, Revolution and Civil War Gill & Macmillan (2005) ISBN 0-7171-3967-0

- Gibbons, Ivan (2015). The British Labour Party and the Establishment of the Irish Free State, 1918–1924. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 107. ISBN 978-1137444080. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- Morgan, Austen (2000). The Belfast Agreement: A Practical Legal Analysis (PDF). The Belfast Press. pp. 66, 68. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- Morgan (2000), p. 68

- Joseph Lee, Ireland 1912–1985: Politics and society, p. 43

- The Times, Court Circular, Buckingham Palace, 6 December 1922.

- "New York Times, 6 December 1922" (PDF). The New York Times. 7 December 1922. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- For further discussion, see: Dáil Éireann – Volume 7 – 20 June 1924 The Boundary Question – Debate Resumed.

- legally, under Article 12 of the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922)

- 'The Irish Border: History, Politics, Culture' Malcolm Anderson, Eberhard Bort (Eds.) pg. 68

- Northern Ireland Parliamentary Debates, 27 October 1922

- "Northern Ireland Parliamentary Report, 7 December 1922". Stormontpapers.ahds.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- The Times, 9 December 1922

- "Northern Ireland Parliamentary Report, 13 December 1922, Volume 2 (1922) / Pages 1191–1192, 13 December 1922". Stormontpapers.ahds.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Edgar Holt Protest in Arms Ch. III Orange Drums, pp.32–33, Putnam London (1960)

- PRESIDENT'S STATEMENT Archived 13 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 1–10 May 1921

- No. 133UCDA P150/1902 De Valera to Lord Justice O'Connor, 4 July 1921

- Lee, J.J.: Ireland 1912–1985 Politics and Society, p. 47, Cambridge University Press (1989, 1990) ISBN 978-0-521-37741-6

- "Correspondence between Lloyd-George and De Valera, June–September 1921". Ucc.ie. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Ashburton Guardian, Volume XLII, Issue 9413, 16 December 1921, Page 5". Paperspast.natlib.govt.nz. 16 December 1921. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "IRELAND IN 1921 by C. J. C. Street O.B.E., M.C". Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Tim Pat Coogan, The Man Who Made Ireland: The Life and Death of Michael Collins. (Palgrave Macmillan, 1992) p 312.

- "Dáil Éireann – Volume 3 – 22 December, 1921 DEBATE ON TREATY". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Document No. 2" text; viewed online January 2011; original held at the National Archives of Ireland in file DE 4/5/13.

- The Times, 22 March 1922

- "HL Deb 27 March 1922 vol 49 cc893-912 IRISH FREE STATE (AGREEMENT) BILL". Hansard.millbanksystems.com. 27 March 1922. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Northern Irish parliamentary reports, online; Vol. 2 (1922), pages 1147–1150". Ahds.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- MFPP Working Paper No. 2, "The Creation and Consolidation of the Irish Border" by KJ Rankin and published in association with Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin and Institute for Governance, Queen's University, Belfast (also printed as IBIS working paper no. 48)

- "Announcement of agreement, Hansard 3 Dec 1925". Hansard.millbanksystems.com. 3 December 1925. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- "Dáil vote to approve the Boundary Commission negotiations". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Section 1(2) of the Government of Ireland Act 1920

- "Hansard – Commons Debate on Irish Free State (Consequential Provisions) Bill, 27 November 1922". Hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Kennedy, Michael J.; Kennedy, Michael (2000). Division and Consensus By Michael Kennedy, Institute of Public Administration (Ireland). ISBN 9781902448305. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- "Documents in Irish Foreign Policy Website – Letter Ref. No. 316 UCDA P4/424". Difp.ie. 12 June 1925. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Dáil Éireann – Volume 63 – 12 August, 1936 Ceisteanna—Questions. Oral Answers. – Lough Foyle Fishery Rights". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Second World War NI website". Secondworldwarni.org. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- British Archives, Catalogue Reference:CAB/129/32 (Memorandum by PM Attlee to Cabinet appending Working Party Report)

- Dáil debates online

- "Dáil Éireann – Volume 408 – 09 May, 1991 Adjournment Debate. – Carlingford Lough Incident". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. 9 May 1991. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Dáil Éireann – Volume 379 – 16 March, 1988 Maritime Jurisdiction (Amendment) Bill, 1987: Second Stage (Resumed)". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. 16 March 1988. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Dáil Éireann – Volume 328 – 31 March, 1981 Written Answers. – Lough Foyle Vessel Explosion". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Department of the Official Report (Hansard), House of Commons, Westminster. "Hansard report of House of Commons Debate on 13 January 2008". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 28 April 2009.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Northern Ireland Assembly Information Office. "Northern Ireland Assembly – Committee Hansard Report, 12 February 2009". Niassembly.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 14 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Foyle 'loughed' in dispute". Londonderry Sentinel. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- "Memorandum of Understanding" (PDF). Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Eds. O'Day A. & Stevenson J., Irish Historical Documents since 1800 (Gill & Macmillan, Dublin 1992) p.201. ISBN 0-7171-1839-8

- Longford, Earl of & O'Neill, T.P. Éamon de Valera (Hutchinson 1970; Arrow paperback 1974) Arrow pp.365–368. ISBN 0-09-909520-3

- "Dáil Éireann – Volume 115 – 10 May 1949 – Protest Against Partition—Motion". Historical-debates.oireachtas.ie. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 28 April 2009.

- Grimes, J. S., From Bricklayer to Bricklayer: The Rhode Island Roots of Congressman John E. Fogarty's Irish-American Nationalism (Providence College, Rhode Island, 1990), p. 7.

- Yeoman, Fran. "Times article 2005 on-line". Wayback.vefsafn.is. Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- "Garret FitzGerald's essay of 2006" (PDF). Ria.ie. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

Further reading

- Denis Gwynn, The History of Partition (1912–1925). Dublin: Browne and Nolan, 1950.

- Michael Laffan, The Partition of Ireland 1911–25. Dublin: Dublin Historical Association, 1983.

- Thomas G. Fraser, Partition in Ireland, India and Palestine: theory and practice.London: Macmillan, 1984.

- Clare O'Halloran, Partition and the limits of Irish nationalism: an ideology under stress. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 1987.

- Austen Morgan, Labour and partition: the Belfast working class, 1905–1923. London: Pluto, 1991.

- Eamon Phoenix, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist politics, partition and the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland. Belfast: Ulster Historical Foundation, 1994.

- Thomas Hennessey, Dividing Ireland: World War 1 and partition. London: Routledge, 1998.

- John Coakley, Ethnic conflict and the two-state solution: the Irish experience of partition. Dublin: Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin, 2004.

- Benedict Kiely, Counties of Contention: a study of the origins and implications of the partition of Ireland. Cork: Mercier Press, 2004.

- Brendan O'Leary, Analysing partition: definition, classification and explanation. Dublin: Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin, 2006

- Brendan O'Leary, Debating Partition: Justifications and Critiques. Dublin: Institute for British-Irish Studies, University College Dublin, 2006.

- Robert Lynch, Northern IRA and the Early Years of Partition. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2006.

- Robert Lynch, The Partition of Ireland: 1918–1925. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

- Margaret O'Callaghan, Genealogies of partition: history, history-writing and the troubles in Ireland. London: Frank Cass; 2006.

- Lillian Laila Vasi, Post-partition limbo states: failed state formation and conflicts in Northern Ireland and Jammu-and-Kashmir. Koln: Lambert Academic Publishing, 2009.

- Stephen Kelly, Fianna Fáil, Partition and Northern Ireland, 1926 – 1971. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2013

External links

- The Partition of Ireland (Workers Solidarity Movement – An anarchist organisation which supports the IRA)

- James Connolly: Labour and the Proposed Partition of Ireland (Marxists Internet Archive)

- The Socialist Environmental Alliance: The SWP and Partition of Ireland (The Blanket)

- Sean O Mearthaile, Partition — what it means for Irish workers (The ETEXT Archives)

- Northern Ireland Timeline: Partition: Civil war 1922–1923 (BBC History). Archived 7 December 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- Home rule for Ireland, Scotland and Wales (LSE Library). Archived 10 August 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- Towards a Lasting Peace in Ireland (Sinn Féin)

- History of the Republic of Ireland (History World)