Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state.[1][2][3][4] Since the mid-19th century, Irish Nationalism has largely taken the form of cultural nationalism based on the principles of national self-determination and popular sovereignty.[5][6][7][2] Early Irish nationalists during the 19th century such as the United Irishmen in the 1790s, Young Irelanders in the 1840s, Fenian Brotherhood during the 1880s and Sinn Féin and Fianna Fáil in the 1920s all styled themselves in various ways after French left-wing radicalism and republicanism.[8][9] Irish nationalism celebrates the culture of Ireland, especially the Irish language, literature, music, and sports. It grew more potent during the period in which all of Ireland was part of the United Kingdom, which led to most of the island gaining independence from the UK in 1921.

Irish nationalists assert that foreign rule has been detrimental to Irish interests. Politically, Irish nationalism gave way to many factions which created conflict, often violent, throughout the island. The chief division affecting nationalism in Ireland is ethno-religious. At the time of the partition of Ireland the majority of the island was Roman Catholic and largely indigenous whilst a sizeable portion of the country, particularly in the north, was Protestant and chiefly descended from people from Great Britain who arrived as settlers during the reign of King James I. Partition was along these ethno-religious lines, with the majority of Ireland gaining independence, while six northern counties remained part of the United Kingdom. Since partition, Irish nationalism often refers to support for Irish reunification.

History

Early development

Generally, Irish nationalism is regarded as having emerged following the Renaissance revival of the concept of the patria and the religious struggle between the ideology of the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. At this early stage in the 16th century, Irish nationalism represented an ideal of the native Gaelic Irish and the Old English banding together in common cause, under the banner of Catholicism and Irish civic identity ("faith and fatherland/motherland"),[10] hoping to protect their land and interests from the New English Protestant forces sponsored by England. This vision sought to overcome the old ethnic divide between Gaeil (the native Irish) and Gaill (the Normans) which had been a feature of Irish life since the 12th century, following the Norman invasion of Ireland.

Protestantism in England introduced a religious element to the 16th-century Tudor conquest of Ireland, as many of the native Gaels and Hiberno-Normans remained Catholic. The Plantations of Ireland dispossessed many native Catholic landowners in favour of Protestant settlers from England and Scotland.[11] In addition, the Plantation of Ulster, which began in 1609, "planted" a sizeable population of English and Scottish Protestant settlers into the north of Ireland.

Irish aristocrats waged many campaigns against the English presence. A prime example is the rebellion of Hugh O'Neill which became known as the Nine Years War of 1594–1603, which aimed to expel the English and make Ireland a Spanish protectorate.[11]

A more significant movement came in the 1640s, after the Irish Rebellion of 1641, when a coalition of Gaelic Irish and Old English Catholics set up a de facto independent Irish state to fight in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms (see Confederate Ireland). The Confederate Catholics of Ireland, also known as the Confederation of Kilkenny, emphasised the idea of Ireland as a Kingdom independent from England, albeit under the same monarch. They demanded autonomy for the Irish Parliament, full rights for Catholics and an end to the confiscation of Catholic-owned land. However, the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–53) destroyed the Confederate cause and resulted in the permanent dispossession of the old Catholic landowning class.

A similar Irish Catholic monarchist movement emerged in the 1680s and 1690s, when Irish Catholic Jacobites supported James II after his deposition in England in the Glorious Revolution of 1688–1689. The Jacobites demanded that Irish Catholics have a majority in an autonomous Irish Parliament, the restoration of confiscated Catholic land, and an Irish-born Lord Deputy of Ireland. Similarly to the Confederates of the 1640s, the Jacobites were conscious of representing the "Irish nation", but were not separatists and largely represented the interests of the landed class as opposed to all the Irish people. Like the Confederates, they also suffered defeat, in the Williamite War in Ireland (1689–1691). Thereafter, the largely English Protestant Ascendancy dominated Irish government and landholding. The Penal Laws discriminated against non-Anglicans. (See also History of Ireland 1536–1691.)

This coupling of religious and ethnic identity – principally Roman Catholic and Gaelic – as well as a consciousness of dispossession and defeat at the hands of British and Protestant forces, became enduring features of Irish nationalism. However, the Irish Catholic movements of the 16th century were invariably led by a small landed and clerical elite. Professor Kevin Whelan has traced the emergence of the modern Catholic-nationalist identity that formed in 1760–1830.[12] Irish historian Marc Caball, on the other hand, claims that "early modern Irish nationalism" began to be established after the Flight of the Earls (1607), based on the concepts of "the indivisibility of Gaelic cultural integrity, territorial sovereignty, and the interlinking of Gaelic identity with profession of the Roman Catholic faith".[13]

Pre-Union

The exclusively Protestant Parliament of Ireland of the eighteenth century repeatedly called for more autonomy from the British Parliament – particularly the repeal of Poynings' Law, which allowed the latter to legislate for Ireland. They were supported by popular sentiment that came from the various publications of William Molyneux about Irish constitutional independence; this was later reinforced by Jonathan Swift's incorporation of these ideas into Drapier's Letters.[14][15]

Parliamentarians who wanted more self-government formed the Irish Patriot Party, led by Henry Grattan, who achieved substantial legislative independence in 1782–83. Grattan and radical elements of the 'Irish Whig' party campaigned in the 1790s for Catholic political equality and a reform of electoral rights.[16] He wanted useful links with Britain to remain, best understood by his comment: 'The channel [the Irish sea] forbids union; the ocean forbids separation'.

Grattan's movement was notable for being both inclusive and nationalist as many of its members were descended from the Anglo/Irish minority. Many other nationalists such as Samuel Neilson, Theobald Wolfe Tone and Robert Emmet were also descended from plantation families which had arrived in Ireland since 1600. From Grattan in the 1770s to Parnell up to 1890, nearly all the leaders of Irish separatism were Protestant nationalists.

Modern Irish nationalism with democratic aspirations began in the 1790s with the founding of the Society of the United Irishmen. It sought to end discrimination against Catholics and Presbyterians and to found an independent Irish republic. Most of the United Irish leaders were Catholic and Presbyterian and inspired by the French Revolution, wanted a society without sectarian divisions, the continuation of which they attributed to the British domination over the country. They were sponsored by the French Republic, which was then the enemy of the Holy See. The United Irishmen led the Irish Rebellion of 1798, which was repressed with great bloodshed. As a result, the Irish Parliament voted to abolish itself in the Act of Union of 1800–01 and thereafter Irish MPs sat in London.

Post-Union

Two forms of Irish nationalism arose from these events. One was a radical movement, known as Irish republicanism. It believed the use of force was necessary to found a secular, egalitarian Irish republic, advocated by groups such as the Young Irelanders, some of whom launched a rebellion in 1848.[17]

The other nationalist tradition was more moderate, urging non-violent means to seek concessions from the British government.[18] While both nationalist traditions were predominantly Catholic in their support base, the hierarchy of the Catholic Church were opposed to republican separatism on the grounds of its violent methods and secular ideology, while they usually supported non-violent reformist nationalism.[19]

Daniel O'Connell was the leader of the moderate tendency. O'Connell, head of the Catholic Association and Repeal Association in the 1820s, '30s and '40s, campaigned for Catholic Emancipation – full political rights for Catholics – and then "Repeal of the Union", or Irish self-government under the Crown. Catholic Emancipation was achieved, but self-government was not. O'Connell's movement was more explicitly Catholic than its eighteenth-century predecessors.[20] It enjoyed the support of the Catholic clergy, who had denounced the United Irishmen and reinforced the association between Irish identity and Catholicism. The Repeal Association used traditional Irish imagery, such as the harp, and located its mass meetings in sites such as Tara and Clontarf which had a special resonance in Irish history.

Repeal Association and Young Ireland

The Great Famine of 1845–49 caused great bitterness among Irish people against the British government, which was perceived as having failed to avert the deaths of up to a million people.[21] British support for the 1860 plebiscites on Italian unification prompted Alexander Martin Sullivan to launch a "National Petition" for a referendum on repeal of the union; in 1861 Daniel O'Donoghue submitted the 423,026 signatures to no effect.[22][23]

The Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) and Fenian Brotherhood were set up in Ireland and the United States, respectively, in 1858 by militant republicans, including Young Irelanders. The latter dissolved into factions after organising unsuccessful raids on Canada by Irish veterans of the American Civil War,[24] and the IRB launched Clan na Gael as a replacement. In Ireland itself, the IRB tried an armed revolt in 1867 but, as it was heavily infiltrated by police informers, the rising was a failure.[25]

In the late 19th century, Irish nationalism became the dominant ideology in Ireland, having a major Parliamentary party in the Parliament of the United Kingdom at Westminster that launched a concerted campaign for self-government.

Land League

Mass nationalist mobilisation began when Isaac Butt's Home Rule League (which had been founded in 1873 but had little following) adopted social issues in the late 1870s – especially the question of land redistribution.[26] Michael Davitt (an IRB member) founded the Irish Land League in 1879 during an agricultural depression to agitate for tenant's rights. Some would argue the land question had a nationalist resonance in Ireland as many Irish Catholics believed that land had been unjustly taken from their ancestors by Protestant English colonists in the 17th-century Plantations of Ireland.[27] Indeed, the Irish landed class was still largely an Anglo-Irish Protestant group in the 19th century. Such perceptions were underlined in the Land league's language and literature.[28] However, others would argue that the Land League had its direct roots in tenant associations formed in the period of agricultural prosperity during the government of Lord Palmerston in the 1850s and 1860s, who were seeking to strengthen the economic gains they had already made.[29] Following the depression of 1879 and the subsequent fall in prices (and hence profits), these farmers were threatened with rising rents and eviction for failure to pay rents. In addition, small farmers, especially in the west faced the prospect of another famine in the harsh winter of 1879. At first, the Land League campaigned for the "Three Fs" – fair rent, free sale and fixity of tenure. Then, as prices for agricultural products fell further and the weather worsened in the mid-1880s, tenants organised themselves by withholding rent during the 1886–1891 Plan of Campaign movement.

Militant nationalists such as the Fenians saw that they could use the groundswell of support for land reform to recruit nationalist support, this is the reason why the New Departure – a decision by the IRB to adopt social issues – occurred in 1879.[30] Republicans from Clan na Gael (who were loath to recognise the British parliament) saw this as an opportunity to recruit the masses to agitate for Irish self-government. This agitation, which became known as the "Land War", became very violent when Land Leaguers resisted evictions of tenant farmers by force and the British Army and Royal Irish Constabulary was used against them. This upheaval eventually resulted in the British government subsidising the sale of landlords' estates to their tenants in the Irish Land Acts authored by William O'Brien. It also provided a mass base for constitutional Irish nationalists who had founded the Home Rule League in 1873. Charles Stewart Parnell (somewhat paradoxically, a Protestant landowner) took over the Land League and used its popularity to launch the Irish National League in 1882 as a support basis for the newly formed Irish Parliamentary Party, to campaign for Home Rule.

Cultural nationalism

An important feature of Irish nationalism from the late 19th century onwards was a commitment to Gaelic Irish culture. A broad intellectual movement, the Celtic Revival, grew up in the late 19th century. Though largely initiated by artists and writers of Protestant or Anglo-Irish background, the movement nonetheless captured the imaginations of idealists from native Irish and Catholic background. Periodicals such as United Ireland, Weekly News, Young Ireland, and Weekly National Press (1891–92), became influential in promoting Ireland's native cultural identity. A frequent contributor, the poet John McDonald's stated aim was "to hasten, as far as in my power lay, Ireland's deliverance".[31]

Other organisations promoting of the Irish language or the Gaelic Revival were the Gaelic League and later Conradh na Gaeilge. The Gaelic Athletic Association was also formed in this era to promote Gaelic football, hurling, and Gaelic handball; it forbade its members to play English sports such as association football, rugby union, and cricket.

Most cultural nationalists were English speakers, and their organisations had little impact in the Irish speaking areas or Gaeltachtaí, where the language has continued to decline (see article). However, these organisations attracted large memberships and were the starting point for many radical Irish nationalists of the early twentieth century, especially the leaders of the Easter Rising of 1916 such as Patrick Pearse,[32] Thomas MacDonagh,[33] and Joseph Plunkett. The main aim was to emphasise an area of difference between Ireland and Germanic England, but the majority of the population continued to speak English.

The cultural Gaelic aspect did not extend into actual politics; while nationalists were interested in the surviving Chiefs of the Name, the descendants of the former Gaelic clan leaders, the chiefs were not involved in politics, nor noticeably interested in the attempt to recreate a Gaelic state.

Home Rule beginnings

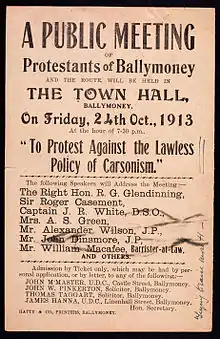

Although Parnell and some other Home Rulers, such as Isaac Butt, were Protestants, Parnell's party was overwhelmingly Catholic. At local branch level, Catholic priests were an important part of its organisation. Home Rule was opposed by Unionists (those who supported the Union with Britain), mostly Protestant and from Ulster under the slogan, "Home Rule is Rome Rule."

At the time, some politicians and members of the British public would have seen this movement as radical and militant. Detractors quoted Charles Stewart Parnell's Cincinnati speech in which he claimed to be collecting money for "bread and lead". He was allegedly sworn into the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood in May 1882. However, the fact that he chose to stay in Westminster following the expulsion of 29 Irish MPs (when those in the Clan expected an exodus of nationalist MPs from Westminster to set up a provisional government in Dublin) and his failure in 1886 to support the Plan of Campaign (an aggressive agrarian programme launched to counter agricultural distress), marked him as an essentially constitutional politician, though not averse to using agitational methods as a means of putting pressure on parliament.

Coinciding as it did with the extension of the franchise in British politics – and with it the opportunity for most Irish Catholics to vote – Parnell's party quickly became an important player in British politics. Home Rule was favoured by William Ewart Gladstone, but opposed by many in the British Liberal and Conservative parties. Home Rule would have meant a devolved Irish parliament within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The first two Irish Home Rule Bills were put before the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1886 and 1893, but they were bitterly resisted and the second bill ultimately defeated in the Conservative's pro-Unionist majority controlled House of Lords.

Following the fall and death of Parnell in 1891 after a divorce crisis, which enabled the Irish Roman Catholic hierarchy to pressure MPs to drop Parnell as their leader, the Irish Party split into two factions, the INL and the INF becoming practically ineffective from 1892 to 1898. Only after the passing of the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898 which granted extensive power to previously non-existent county councils, allowing nationalists for the first time through local elections to democratically run local affairs previously under the control of landlord dominated "Grand Juries", and William O'Brien founding the United Irish League that year, did the Irish Parliamentary Party reunite under John Redmond in January 1900, returning to its former strength in the following September general election.

Transformation of rural Ireland

The first decade of the twentieth century saw considerable advancement in rural economic and social development in Ireland where 60% of the population lived.[34] The introduction of local self-government in 1898 created a class of experienced politicians capable of later taking over national self-government in the 1920s. O'Brien's attainment of the 1903 Wyndham Land Act (the culmination of land agitation since the 1880s) abolished landlordism, and made it easier for tenant farmers to purchase lands, financed and guaranteed by the government. By 1914, 75 per cent of occupiers were buying out their landlords' freehold interest through the Land Commission, mostly under the Land Acts of 1903 and 1909.[35] O'Brien then pursued and won in alliance with the Irish Land and Labour Association and D.D. Sheehan, who followed in the footsteps of Michael Davitt, the landmark 1906 and 1911 Labourers (Ireland) Acts, where the Liberal government financed 40,000 rural labourers to become proprietors of their own cottage homes, each on an acre of land. "It is not an exaggeration to term it a social revolution, and it was the first large-scale rural public-housing scheme in the country, with up to a quarter of a million housed under the Labourers Acts up to 1921, the majority erected by 1916",[36] changing the face of rural Ireland.

The combination of land reform and devolved local government gave Irish nationalists an economic political base on which to base their demands for self-government. Some in the British administration felt initially that paying for such a degree of land and housing reform amounted to an unofficial policy of "killing home rule by kindness", yet by 1914 some form of Home Rule for most of Ireland was guaranteed. This was shelved on the outbreak of World War I in August 1914.

A new source of radical Irish nationalism developed in the same period in the cities outside Ulster. In 1896, James Connolly, founded the Irish Socialist Republican Party in Dublin. Connolly's party was small and unsuccessful in elections, but his fusion of socialism and Irish republicanism was to have a sustained impact on republican thought. In 1913, during the general strike known as the Dublin Lockout, Connolly and James Larkin formed a workers militia, the Irish Citizen Army, to defend strikers from the police. While initially a purely defensive body, under Connolly's leadership, the ICA became a revolutionary body, dedicated to an independent Workers Republic in Ireland. After the outbreak of the First World War, Connolly became determined to launch an insurrection to this end.

Home Rule crisis 1912–14

Home Rule was eventually won by John Redmond and the Irish Parliamentary Party and granted under the Third Home Rule Act 1914. However, Irish self-government was limited by the prospect of partition of Ireland between north and south. This idea had first been mooted under the Second Home Rule Bill in 1893. In 1912, following the entry of the Third Home Rule Bill through the House of Commons, unionists organised mass resistance to its implementation, organising around the "Ulster Covenant". In 1912 they formed the Ulster Volunteers, an armed wing of Ulster Unionism who stated that they would resist Home Rule by force. British Conservatives supported this stance. In addition, in 1914 British officers based at the Curragh Camp indicated that they would be unwilling to act against the Ulster Volunteers should they be ordered to.

In response, Nationalists formed their own paramilitary group, the Irish Volunteers, to ensure the implementation of Home Rule. It looked for several months in 1914 as if civil war was imminent between the two armed factions. Only the All-for-Ireland League party advocated granting every conceivable concession to Ulster to stave off a partition amendment. Redmond rejected their proposals. The amended Home Rule Act was passed and placed with Royal Assent on the statute books, but was suspended after the outbreak of World War I in 1914, until the end of the war. This led radical republican groups to argue that Irish independence could never be won peacefully and gave the northern question little thought at all.

World War I and the Easter Rising

The Irish Volunteer movement was divided over the attitude of their leadership to Ireland's involvement in World War I. The majority followed John Redmond in support of the British and Allied war effort, seeing it as the only option to ensure the enactment of Home Rule after the war, Redmond saying "you will return as an armed army capable of confronting Ulster's opposition to Home Rule". They split off from the main movement and formed the National Volunteers, and were among the 180,000 Irishmen who served in Irish regiments of the Irish 10th and 16th Divisions of the New British Army formed for the War.

A minority of the Irish Volunteers, mostly led by members of the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), refused to support the War and kept their arms to guarantee the passage of Home Rule. Within this grouping, another faction planned an insurrection against British rule in Ireland, while the War was going on. Critical in this regard were Patrick Pearse,[37] Thomas MacDonagh, and Thomas Clarke. These men were part of an inner circle that were operating in secret within the ranks of the IRB to plan this rising unknown to the rest of the volunteers.[38] James Connolly, the labour leader, first intended to launch his own insurrection for an Irish Socialist Republic decided early in 1916 to combine forces with the IRB. In April 1916, just over a thousand dissident Volunteers and 250 members of the Citizen's Army launched the Easter Rising in the Dublin General Post Office and, in the Easter Proclamation, proclaimed the independence of the Irish Republic. The Rising was put down within a week, at a cost of about 500 killed, mainly unengaged civilians.[39] Although the rising failed, Britain's General Maxwell executed fifteen of the Rising's leaders, including Pearse, MacDonagh, Clarke and Connolly, and arrested some 3,000 political activists which led to widespread public sympathy for the rebel's cause. Following this example, physical force republicanism became increasingly powerful and, for the following seven years or so, became the dominant force in Ireland, securing substantial independence but at a cost of dividing Ireland.[40]

The Irish Parliamentary Party was discredited after Home Rule had been suspended at the outbreak of World War I, in the belief that the war would be over by the end of 1915, then by the severe losses suffered by Irish battalions in Gallipoli at Cape Helles and on the Western Front. They were also damaged by the harsh British response to the Easter Rising, who treated the rebellion as treason in time of war when they declared martial law in Ireland. Moderate constitutional nationalism as represented by the Irish Party was in due course eclipsed by Sinn Féin — a hitherto small party which the British had (mistakenly) blamed for the Rising and subsequently taken over as a vehicle for Irish Republicanism.

Two further attempts to implement Home Rule in 1916 and 1917 also failed when John Redmond, leader of the Irish Party, refused to concede to partition while accepting there could be no coercion of Ulster. An Irish Convention to resolve the deadlock was established in July 1917 by the British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, its members both nationalists and unionists tasked with finding a means of implementing Home Rule. However, Sinn Féin refused to take part in the Convention as it refused to discuss the possibility of full Irish independence. The Ulster unionists led by Edward Carson insisted on the partition of six Ulster counties from the rest of Ireland,[41] stating that the 1916 rebellion proved a parliament in Dublin could not be trusted.

The Convention's work was disrupted in March 1918 by Redmond's death and the fierce German Spring Offensive on the Western Front, causing Britain to attempt to contemplate extending conscription to Ireland. This was extremely unpopular, opposed both by the Irish Parliamentary Party under its new leader John Dillon, the All-for-Ireland Party as well as Sinn Féin and other national bodies. It resulted in the Conscription Crisis of 1918. In May at the height of the crisis 73 prominent Sinn Féiners were arrested on the grounds of an alleged German Plot. Both these events contributed to a widespread rise in support for Sinn Féin and the Volunteers.[42] The Armistice ended the war in November, and was followed by elections.

Militant separatism and Irish independence

In the General election of 1918, Sinn Féin won 73 seats, 25 of these unopposed, or statistically nearly 70% of Irish representation, under the British "First past the post" voting-system, but had a minority representation in Ulster. They achieved a total of 476,087 (46.9%) of votes polled for 48 seats, compared to 220,837 (21.7%) votes polled by the IPP for only six seats, who due to the "first past the post" voting system did not win a proportional share of seats.[43] Unionists (including Unionist Labour) votes were 305,206 (30.2%)[44]

The Sinn Féin MPs refused to take their seats in Westminster, 27 of these (the rest were either still imprisoned or impaired) setting up their own Parliament called the Dáil Éireann in January 1919 and proclaimed the Irish Republic to be in existence. Nationalists in the south of Ireland, impatient with the lack of progress on Irish self-government, tended to ignore the unresolved and volatile Ulster situation, generally arguing that unionists had no choice but to ultimately follow. On 11 September 1919, the British proscribed the Dáil, it had met nine times, declaring it an illegal assembly, Ireland being still part of the United Kingdom. In 1919, a guerilla war broke out between the Irish Republican Army (IRA) (as the Irish Volunteers were now calling themselves) and the British security forces[45] (See Irish War of Independence).

The campaign created tensions between the political and military sides of the nationalist movement. The IRA, nominally subject to the Dáil, in practice, often acted on its own initiative. At the top, the IRA leadership, of Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy, operated with little reference to Cathal Brugha, the Dáil's Minister for Defence or Éamon de Valera, the President of the Irish Republic – at best giving them a supervisory role.[46] At local level, IRA commanders such as Dan Breen, Sean Moylan, Tom Barry, Sean MacEoin, Liam Lynch and others avoided contact with the IRA command, let alone the Dáil itself.[47] This meant that the violence of the War of Independence rapidly escalated beyond what many in Sinn Féin and Dáil were happy with.[47] Arthur Griffith, for example, favoured passive resistance over the use of force, but he could do little to affect the cycle of violence between IRA guerrillas[47] and Crown forces that emerged over 1919–1920. The military conflict produced only a handful of killings in 1919, but steadily escalated from the summer of 1920 onwards with the introduction of the paramilitary police forces, the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division into Ireland. From November 1920 to July 1921, over 1000 people lost their lives in the conflict (compared to c.400 until then).

Present day

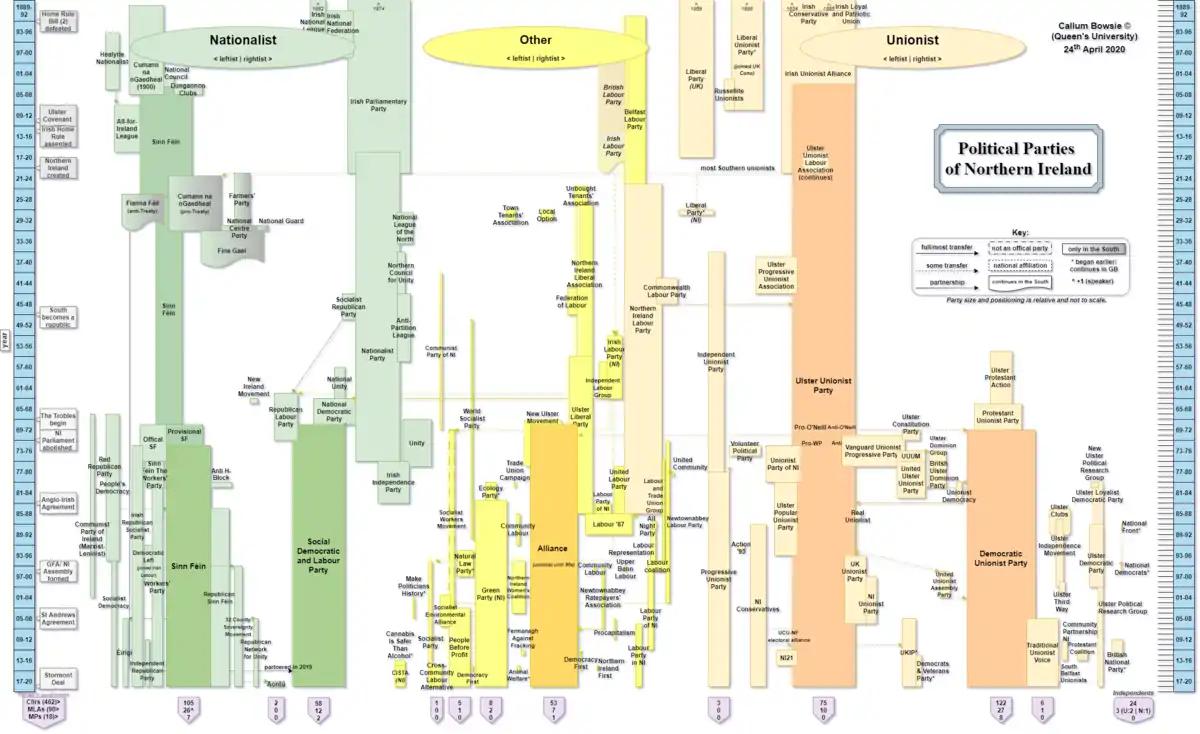

Northern Ireland is not a part of the Republic, but it has a nationalist minority who would prefer to be part of a united Ireland. In Northern Ireland, the term "nationalist" is used to refer either to the Catholic population in general or the supporters of the moderate Social Democratic and Labour Party. "Nationalism" in this restricted meaning refers to a political tradition that favours an independent, united Ireland achieved by non-violent means. The more militant strand of nationalism, as espoused by Sinn Féin, is generally described as "republican" and was regarded as somewhat distinct, although the modern-day party claims to be a constitutional party committed to exclusively peaceful and democratic means.

56% of Northern Irish voters voted for the United Kingdom to remain a part of the European Union in the 23 June 2016 Referendum in which the country as a whole voted to leave the union. The results in Northern Ireland were influenced by fears of a strong border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland as well as by fears of a hard border breaking the Good Friday Agreement.[48]

References

Citations

- https://reviews.history.ac.uk/review/704

- Murray, Peter (1 January 1993). "Irish cultural nationalism in the United Kingdom state: Politics and the Gaelic League 1900–18". Irish Political Studies. 8 (1): 55–72. doi:10.1080/07907189308406508 – via Taylor and Francis+NEJM.

- CAIN: Politics – An Outline of the Main Political 'Solutions' to the Conflict, United Ireland Definition.

- Tonge, Jonathan (2013). Northern Ireland: Conflict and Change. Routledge. p. 201. ISBN 978-1317875185. Retrieved 12 April 2017.

- Sa'adah 2003, 17–20.

- Smith 1999, 30.

- Delanty, Gerard; Kumar, Krishan. The SAGE handbook of nations and nationalism. London, England, UK; Thousand Oaks, California, USA; New Delhi, India: Sage Publications, Ltd, 2006, 542.

- Metscher, Thomas (25 November 1989). "Between 1789 and 1798 : the "Revolution in the Form of Thought" in Ireland". Études irlandaises. 14 (1): 139–146. doi:10.3406/irlan.1989.2517 – via www.persee.fr.

- Murray, Peter (1993). "Irish cultural nationalism in the United Kingdom state: Politics and the Gaelic League 1900–18". Irish Political Studies. 8: 55–72. doi:10.1080/07907189308406508.

- "Faith & Fatherland in sixteenth-century Ireland". History Ireland. 21 July 2015.

- Kee 1972, p. 9–15.

- The Tree of Liberty: Radicalism, Catholicism and the Construction of Irish Identity 1760–1830 1996, Cork UP; and see some online notes on Whelan.

- Valone, David A.; Jill Marie Bradbury (2008). Anglo-Irish Identities 1571–1845. Bucknell University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0-8387-5713-0.

- Jonathan Swift: Volume III by Irvin Ehrenpreis

- Jonathan Swift and Ireland by Oliver W. Ferguson

- Kelly, J. Henry Grattan (Dundalgan Press 1993) pp.27–35 ISBN 0-85221-121-X

- Kee 1972, p. 243–290.

- Kee 1972, p. 179–232.

- Kee 1972, p. 173 et passim.

- Kee 1972, p. 179–193.

- Kee 1972, p. 170–178.

- Loughlin, James (2007). The British Monarchy and Ireland: 1800 to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 97–98. ISBN 9780521843720. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Jenkins, Brian (2014). Irish Nationalism and the British State: From Repeal to Revolutionary Nationalism. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. pp. 131–132, 267. ISBN 9780773560055. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Senior, Hereward (1991). The Last Invasion of Canada: The Fenian Raids, 1866-1870. Dundurn. ISBN 9781550020854. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Kee 1972, p. 330 et passim.

- Kee 1972, p. 351–376.

- Kee 1972, p. 15–21.

- Kee 1972, p. 364–376.

- Kee 1972, p. 299–311.

- Kee 1972, p. 330–351.

- O'Donoghue 1892, pp. 144.

- Sean Farrell Moran, "Patrick Pearse and the European Revolt Against Reason," Journal of the History of Ideas, 1989; Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption, (1994),

- Johann Norstedt, Thomas MacDonagh, (1980)

- Kee 1972, p. 422–426.

- Ferriter, Diarmaid, The Transformation of Ireland 1900–2000 (2005) pp. 38+62

- Ferriter, Diarmaid, The Transformation of Ireland 1900–2000, (2004) pp 159

- Sean Farrell Moran, "Patrick Pearse and the Politics of Redemption", (1995), Ruth Dudley Edwards, "Patrick Pearse and the Triumph of Failure," (1974), Joost Augustin, "Patrick Pearse," (2009).

- Robert., Kee (1989). The green flag. Harmondsworth: Penguin. ISBN 0140111042. OCLC 19668723.

- Kee 1972, p. 548–591.

- Kee 1972, p. 591–719.

- ME Collins, Ireland 1868–1966, page 240

- Sovereignty and partition, 1912–1949, p. 59, M. E. Collins, Edco Publishing (2004) ISBN 1-84536-040-0

- Sovereignty and partition, 1912–1949, p.62, M. E. Collins, Edco Publishing (2004) ISBN 1-84536-040-0

- B.M. Walker Parliamentary Election Results in Ireland, 1801–1822

- Kee 1972, p. 651–698.

- Kee 1972, p. 611 et passim.

- Kee 1972, p. 651–656.

- "Now, IRA stands for I Renounce Arms". The Economist. 28 July 2005.

Sources

- Kee, Robert (1972). The Green Flag: A History of Irish Nationalism. ISBN 0-297-17987-X.

- O'Donoghue, David James (1892). The Poets of Ireland: A Biographical Dictionary with Bibliographical Particulars (PDF).

Further reading

- Brundage, David. Irish Nationalists in America: The Politics of Exile, 1798–1998 (Oxford UP, 2016). x, 288

- Boyce, D. George. Nationalism in Ireland, 1982.

- Campbell, F. Land and Revolution,2005

- Cronin, Sean. Irish Nationalism: Its Roots and Ideology, 1980.

- Edwards, Ruth Dudley, Patrick Pearse: The Triumph of Failure, 1977.

- Elliot, Marianne, Wolfe Tone, 1989.

- English, Richard. Irish Freedom, 2008.

- Garvin, Tom. The Evolution of Irish Nationalist Politics, 1981; Nationalist Revolutionaries in Ireland, 1858-1928, 1987

- Kee, Robert. The Green Flag, 1976.

- MacDonagh, Oliver. States of Mind, 1983

- McBride, Lawrence. Images, Icons, and the Irish Nationalist Imagination, 1999.

- McBride, Lawrence. Reading Irish Histories, 2003.

- Maume, Patrick. The Long Gestation, 1999.

- Nelson, Bruce. Irish Nationalists and the Making of the Irish Race. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2012.

- Strauss, E. Irish Nationalism and British Democracy, 1951.

- O'Farrell, Patrick. Ireland's English Question, 1971.

- Phoenix, E. Northern Nationalism,

- Ward, Margaret. Unimaginable Revolutionaries: Women and Irish Nationalism, 1983

- Zách, L. (2020). ‘The first of the small nations’: The significance of central European small states in Irish nationalist political rhetoric, 1918–22. Irish Historical Studies, 44(165), 25-40.

External links

- Irish Nationalism (Archived 2009-10-31) – ninemsn Encarta (short introduction)