Magdalene College, Cambridge

Magdalene College (/ˈmɔːdlɪn/ MAWD-lin)[6] is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1428 as a Benedictine hostel, in time coming to be known as Buckingham College, before being refounded in 1542 as the College of St Mary Magdalene. Magdalene counted some of the greatest men in the realm among its benefactors, including Britain's premier noble the Duke of Norfolk, the Duke of Buckingham and Lord Chief Justice Christopher Wray.[7] Thomas Audley, Lord Chancellor under Henry VIII, was responsible for the refoundation of the college and also established its motto—garde ta foy (Old French: "keep your faith"). Audley's successors in the Mastership and as benefactors of the College were, however, prone to dire ends; several benefactors were arraigned at various stages on charges of high treason and executed.[8]

| Magdalene College | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Cambridge | ||||||||||||

Second Court, Magdalene College | ||||||||||||

Arms of Magdalene College, being the arms of Thomas Audley, 1st Baron Audley of Walden. Blazon: Quarterly per pale indented Or and azure, on a bend of the second between in sinister chief and dexter base an eagle displayed a fret between two martlets of the first. | ||||||||||||

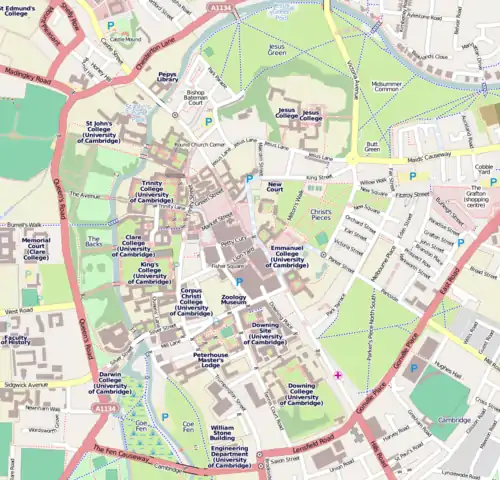

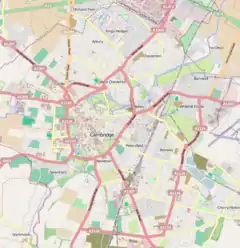

| Location | Magdalene Street (map) | |||||||||||

| Full name | The College of Saint Mary Magdalene at the University of Cambridge | |||||||||||

| Latin name | Collegium Beatae Mariae Magdalenae | |||||||||||

| Abbreviation | M[1] | |||||||||||

| Motto | Garde ta Foy (Old French) | |||||||||||

| Motto in English | Keep your faith | |||||||||||

| Founders | ||||||||||||

| Established | 1428[2] Refounded 1542[3] | |||||||||||

| Named after | Mary Magdalene | |||||||||||

| Previous names | Buckingham College (1428–1542) | |||||||||||

| Sister college | Magdalen College, Oxford | |||||||||||

| Master | Sir Christopher Greenwood | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 353[4] | |||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 203[4] | |||||||||||

| Endowment | £56.3m (as of 30 June 2017)[5] | |||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||

| JCR | jcr | |||||||||||

| MCR | mcr | |||||||||||

| Boat club | magdaleneboatclub | |||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||

Location in Central Cambridge  Location in Cambridge | ||||||||||||

The college's most famous alumnus is the 17th-century chronicler Samuel Pepys. His papers and books were donated to the college upon his death and are housed in the Pepys Library in the Pepys Building. A portrait of the diarist by Peter Lely hangs in the Hall.

Magdalene is noted for its 'traditional' style: it boasts a well-regarded candlelit formal hall (held every evening) and was the last all-male college in Oxford or Cambridge to admit women in 1988 (Oriel College was the last in Oxford, admitting women in 1986). This change resulted in protests by some male undergraduates, including the wearing of black armbands and flying the college flag at half-mast.[8]

Magdalene's old buildings are representative of the college's ramshackle growth from a monks' foundation into a centre of education. It is also distinctive in that most of the old buildings are in brick rather than stone (save for the frontage of the Pepys Building). Magdalene Street divides the most ancient courts from more recent developments. One of the accommodation blocks in the newer part of the college was built by Sir Edwin Lutyens in the early 1930s. Opened in 2005, Cripps Court, on Chesterton Road, features new undergraduate rooms and conference facilities.

Magdalene remains one of the smaller colleges in the University, numbering some 300 undergraduates. Magdalene has been an academically strong-performing college over the past decade, achieving an average of ninth in the Tompkins Table and coming second in 2015.

History

Buckingham College

Magdalene College was first founded in 1428 as Monk's Hostel, which hosted Benedictine student monks. The secluded location of the hostel was chosen because it was separated from the town centre by the River Cam and protected by Cambridge Castle. The main buildings of the college were first constructed in the 1470s under the leadership of John de Wisbech, then Abbot of Crowland.[9] Under the patronage of Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, the institution was renamed Buckingham College.[2]

In the 16th century, the Church of England broke away from the Papacy. With the subsequent Dissolution of the Monasteries, the parent abbey of Buckingham College, Crowland Abbey, was dissolved. However, the college remained in operation.[10]

Refoundation

Walden Abbey, one of the Benedictine abbeys associated with Buckingham College, came into the possession of Thomas Audley after the Dissolution of the Monasteries. On 3 April 1542 Audley refounded Buckingham College as the College of Saint Mary Magdalene.[11] Derived from Audley were the arms of Magdalene, including the motto Garde Ta Foy (from Old French for "keep your faith"), and the wyvern as the crest.[3]

Thomas Audley died in 1544 aged 56, only two years after he re-founded the college. He donated to the college seven acres of property at Aldgate in London, which was his reward from Henry VIII for disposing of Anne Boleyn. This property would have brought enormous income had it been retained by the college.[3] However, under the conspiracy of the Elizabethan banker Benedict Spinola, the property was permanently alienated to the Crown in 1574.[12] The transaction involved Spinola luring the master and fellows of the time to accept an increase in the annual rental from £9 to £15 a year in exchange for the property. The loss of the Aldgate property left the college in extreme poverty, and the street front of the college was only completed in the 1580s under the generosity of Christopher Wray, then Lord Chief Justice of the Queen's Bench. The transaction was "almost certainly illegal", and was contested multiple times without success.[13] The first and most famous such lawsuit was pursued in 1615 by Barnaby Goche, who was master of the college between 1604 and 1626. This court case landed Goche and the senior fellow in prison for two years.[14] Goche was subsequently offered £10,000 as a compromise, which he refused to accept. When the Quayside development site of Magdalene College was completed in 1989, a gargoyle of Spinola which spits water into the Cam was installed as a "revenge at last".[13]

In 1650, Samuel Pepys joined the college. He was best known for his private diaries, known to critics as the Pepys Diary, which provided a major eyewitness account for the Great Fire of London of 1666.[15][16] Pepys was remembered by the Pepys Library, built around 1700,[17] where the original manuscripts of his diaries and naval records are kept, in addition to his collection of printed books and engravings in their original bookcases. Pepys stipulated in his will that the library was to be left to Magdalene, and have been kept at the college since their donation by Pepys's nephew, John Jackson, in 1724.[18] The building is also home to Magdalene College library.[18]

Enlightenment

Daniel Waterland, a theologian by training, became master of the college in 1714 and prescribed a new curriculum for undergraduate students at Magdalene.[19] His new curriculum included Mathematics, Newtonian Physics, Geography and Astronomy, as well as Classics, Logic and Metaphysics. Waterland was also successful in attracting financial aid for the college, including funds for scholarships.[20] The mathematician Edward Waring was among those who joined the college during this period.[21]

In 1781, Peter Peckard, one of the earliest abolitionists, became master of Magdalene. The Zong massacre of 1781 prompted Peckard to speak strongly against slave trade in his sermons, some of which were published as tracts and pamphlets.[22] Peckard set the college on the course of achieving a wider reputation of scholarship and sound thinking, and was later appointed as vice-chancellor of Cambridge University.[20]

Magdalene continued to be a liberal college through the Victorian era. The college had more liberal admissions policies than most, admitting Arthur Cohen, the first practising Jew to graduate from Cambridge.[23] During the same period, Magdalene also admitted Catholic students such as Charles Januarius Acton, and Asian students who were excluded from many other colleges until after the First World War.[24]

Modern development

The modern development of Magdalene was shaped by A. C. Benson, master from 1915 to 1925.[25] His enthusiasm and attention to detail produced outstanding pieces of poems, essays and literary criticism; his diaries were also studied by many later critics. His financial generosity effected significant impact on the modern appearance of the college grounds: at least 20 inscriptions around the college refer to him.[26] In 1930, Benson Court was constructed and named after him.[17]

From 1972, the previously all-male colleges in Cambridge started admitting women, the first three being Churchill, Clare and King's.[27] In 1985, Oriel College, Oxford, admitted women, making Magdalene the only surviving all-male Oxbridge college. The following year, Magdalene made the controversial decision to admit women and become co-residential.[28] When women eventually joined the college in 1988, some male students protested by wearing black arm-bands and flying the college flag at half-mast.[8]

Although the historical perception of Magdalene's bias towards undergraduate applicants from independent schools persists,[29] Magdalene now has an evenly mixed student body in terms of sex, race and education background.[28] In recent years, Magdalene's access programme has attracted many applicants from state schools, especially from North West England;[30] and the college's close affiliation with international students' bursaries such as the Prince Philip Scholarship and the Jardine Foundation has attracted many applicants from Southeast Asia, most notably Wong Yan Lung who went on to become Secretary for Justice for Hong Kong.[31]

Buildings and grounds

Magdalene College is located at the bend of the River Cam on the northwestern side of the town centre, at the foot of Castle Hill. The college was deliberately built on the opposite end of Magdalene Bridge from the town centre so that the Benedictine student-monks would be secluded from the business and temptations of the town.[32] As such, it was the first Cambridge college to be built on the northwestern side of the Cam.[17] The college's main site was previously settled during the Roman occupation of England.[2]

The college's buildings are distributed on both sides of the river, and is roughly divided into four areas: the main site, where the oldest buildings including the porter's lodge and the Pepys Library are located; The Village, which was built in the 1930s and consists exclusively of student accommodation; Quayside, built on the southeastern side of the river in the 1980s as an investment project which also provides student accommodation;[33] and Cripps Court, built in the 2000s for extra conference facilities and accommodation.[34]

Main site

The main site of the college is the area bounded by Magdalene Street, Chesterton Lane and the River Cam. It is the first area to be populated by college buildings since as early as the 1470s.[2] This area includes Magdalene's First Court, Second Court, Fellows' Garden, and the buildings surrounding them such as the porters' lodge, the Master's Lodge, and the Pepys Library.[35]

Porter's lodge and First Court

Situated on the north-east side of Magdalene Street is the porter's lodge. It is the place where mail to members of the college is delivered and distributed. Past the gatehouse by which the porter's lodge is situated lies First Court.[35] The First Court was the earliest court to be built. From 1760 the Court was faced with stucco, but most of the buildings were restored in a project between 1953 and 1966.[36] The chapel was the first to be built around 1470, while the gatehouse including the porter's lodge and the street-front of the college did not exist until 1585.[33]

The chapel lies in the north range of First Court, and its original construction dates to 1470-72. However, later renovation works meant that little of the original chapel other than the original roof remains. Since the college is dedicated to Mary Magdalene, much of the chapel's artwork describes her story. The glass windows on the eastern wall of the chapel are entirely dedicated to the encounters between Mary Magdalene and Jesus Christ around the time of the crucifixion of Jesus: anointing Jesus with her jug of ointment, watching the crucifixion, weeping at the tomb and recognising Jesus after his resurrection. Compared to most other Cambridge colleges of medieval origin, Magdalene's chapel is much smaller in line with the college's relatively small population.[37] Despite its smaller size, however, the chapel's physical proportions are in keeping with those of other medieval Oxbridge college chapels, reflecting the traditional layout of Solomon's Temple: the ratio of Magdalene's antechapel, choir, and sanctuary (1:4:2) matches that of the Temple's porch, holy place, and holy of holies.[38] In 2000, the chapel received a new Baroque-style pipe organ built by Goetze & Gwynn.[39]

Past the chapel, the hall separates the First Court to the west and the Second Court to the east. This is where daily formal dinners are served. The hall itself was first built in the early 16th century, again with many later refurbishments but never gas or electric lighting—Magdalene's hall is unique in Oxbridge in relying solely on candlelight.[40] To the far end of the hall is the High Table, placed on a platform one step above ground level, where fellows and their guests dine. Students dine at three long benches in front of and perpendicular to the High Table and spanning to the entrance. Flanking the entrance is a double staircase leading to a minstrels' gallery and the senior combination room. The walls of the hall are decorated with 15 portraits of notable benefactors and past members.[33]

Both the old and new Master's Lodges are located just to the north of first court. The old Master's Lodge, connected directly to the building on which the porter's lodge was situated, was built in the 16th century and vacated in 1835. The Master's Lodge then moved to a new location about 50m north of the previous location.[35] This new lodge was subsequently torn down and rebuilt in 1967 to give the Master a less grandiose, but more comfortable residence. The building which used to be first Master's Lodge is now known as Old Lodge and is predominantly used for student accommodation.[33] Other than Old Lodge, there are also student rooms scattered around the buildings surrounding First Court, including the areas on top of the hall.[35]

Second Court and gardens

Past the formal hall, the Second Court is most clearly marked by the Pepys Building, where the Pepys Library is housed. The architect and polymath Robert Hooke, otherwise best known for coining the idea of a biological cell, participated in designing this building in 1677, and construction carried on from then until the 1700s because of the college's lack of money.[33] The inscription on the arch in front of the building, Bibliotheca Pepysiana 1724, refers to the year in which the Pepys Diary was donated to the college, rather than the year in which the building was completed.[41] Because of the famous Pepys Diary, the Pepys Library became a popular tourist destination in Cambridge.[8] The ground and basement levels of the Pepys Building host the college library where undergraduate course books are available, and is therefore a major study spot for undergraduates.[33] The Pepys Building was constructed in such a way that it would provide a good view of the Fellows' Garden.[42] Construction of a new College Library began in 2018; the new building, designed by Niall McLaughlin Architects, will offer three times more space.[43][44]

Also situated on Second Court is Bright's Building, named after Mynors Bright, who was most famous for having deciphered the Pepys Diary. It was built in 1908–09 by Aston Webb to provide extra accommodation to host increasing numbers of undergraduate students.[17] The largest room in Bright's Building is Ramsay Hall, named after Allen Beville Ramsay. The room was originally intended to be a lecture room, but it was later refurbished in 1949 to become the college's canteen.[33]

The Fellows' Garden, situated behind Pepys Building, included a Roman-era flood barrier bank which became today's Monk's Walk, a raised footpath leading from the south side of Pepys Building to the exit of the Fellows' Garden on Chesterton Lane. At the time of the college's establishment in 1428, the Fellows' Garden was a series of fishponds. The fishponds were filled between 1586 and 1609, but it was not until the 1660s that plans to cultivate a garden on the land were realised. Most of the trees planted in the original plan of the garden were chopped down and replaced in a renovation in the early 1900s, under the instruction of botanist Walter Gardiner. Most of the newly planted trees were black poplars and its variant, Lombardy poplars. Some fruit trees, such as quince, cherry and plum trees, were later planted in the 1980s-90s. Squirrels, and the occasional woodpecker may be spotted in the garden; there are also a few flowerbeds in the garden in which the gardeners grow seasonal flowers.[42] Near the northwest corner of the Fellows’ Garden lies a Victorian pet cemetery with several gravestones and statues of departed dogs and cats of the College.[45]

Adjacent to the Fellows' Garden are two other gardens: the Master's Garden, which is part of the Master's Lodge and separated from the Fellows' Garden by a brick wall,[33] and the River Court, a small, brick-paved patch of land between Bright's Building and the River Cam, where seasonal flowers are on display in the flowerbeds.[41]

The Village

The area of the college across Magdalene Street from porter's lodge, bounded by Magdalene Street, Northampton Street, the River Cam and St John's College is known as the Magdalene Village.[46] It includes Benson Court, Mallory Court and Buckingham Court, and consists almost exclusively of student accommodation.[41] The whole area of the Village was gradually developed over a period of 45 years by three different architects, Harry Redfern, Sir Edwin Lutyens and David Roberts. The first building to be developed was Mallory Court B (1925–26) and the last was the new Buckingham Court building (1968–70). Lutyens had an original plan which involved demolishing many existing buildings in the area and constructing new buildings that matched the general look and feel of the college's main site, but this plan was scrapped due to insufficient funding and the only part of Lutyens' plan that was realised was the Lutyens building.[33]

Passing through an obscure wooden gate opposite the porter's lodge, the open courtyard of Benson Court can be seen. Benson Court was named after A. C. Benson, master of Magdalene College from 1915 to 1925. Benson was best known for writing the lyrics of Land of Hope and Glory, a British patriotic song set to the tune of Edward Elgar's Pomp and Circumstance March No. 1.[41] The cottages to either side of the entrance pathway are all pre-existing buildings that were converted into student accommodation in the 1960s. In particular, Benson Court H is one of the few buildings in college whose structure survived from the 16th century, and presents its 17th-century facade which was previously known as Cross Keys Inn to the street front of Magdalene Street.[33] To the left of the courtyard is a gentle grassy slope that leads to the "Magdalene beach", where the college punts are moored and parties are held in the summer.[47]

Across the courtyard is the Lutyens building, also designated Benson A-E, which was built and named after Sir Edwin Lutyens, the architect who planned much of the Village. Due to a lack of funding, it was the only part of Lutyens' original grandiose plan that was actually built. Part of the building's cost was sponsored by subscriptions raised by Harvard in memory of Henry Dunster, who studied in Magdalene in 1627-30 and later became a founding father of Harvard University. Hence, the crest of Harvard with the inscription Veritas can be found at the entrance to the D staircase.[33] Each staircase in the building had slightly different banister designs, which Lutyens explained was "to help Magdalene men to feel in the dark whether they were entering the correct staircase".[48] The Lutyens building currently hosts about 60 students and fellows as well as the college launderette.[49]

Another two courts can be found to the northwest of Benson Court: Mallory Court and Buckingham Court. Mallory Court was named after George Mallory, the British mountaineer who famously answered "Because it's there" when asked why he wanted to climb Mount Everest.[50] The court itself comprises student rooms, some new and some converted from existing buildings which include a defunct brewery. Buckingham Court has two groups of buildings, which includes the "Tan Yard Cottages" incorporated to the college and refurbished in 1966, and a new building which contains the college's car park. The new Buckingham building, completed in 1970, marked the completion of the entire Magdalene Village.[33]

Quayside

Most of the buildings bounded by the River Cam, Bridge Street and Thompson's Lane are owned by Magdalene College, despite being completely covered by shop-fronts and restaurants on the ground level. Many of these buildings are part of the Quayside development project, built between 1983–89, as part of a business plan of the college. As for student accommodation, this part of the college includes the Bridge Street and Thompson's Lane hostels.[51]

Cripps Court

Situated on the opposite side of Chesterton Road from the main site of the college, Cripps Court is the newest part of Magdalene. It was built between 2003-05 in response to increasing demands for extra accommodation and conference facilities. The site of Cripps Court is a natural southerly slope, which can be seen from the stepped courtyard in between the buildings.[52] The court was sponsored by, and named after, the Cripps family headed by Humphrey Cripps. It contains a 142-seat auditorium,[53] 5 seminar rooms, an oak-roofed event gallery also called the orangery, and about 60 student rooms.[54]

Events and traditions

Spelling and pronunciation of name

The college is officially known as "The College of Saint Mary Magdalene", with "Magdalene" customarily pronounced "Maudlyn" (/ˈmɔːdlɪn/ MAWD-lin). The name was chosen when Thomas Audley re-founded and dedicated the college to Mary Magdalene in 1542. In early documents, the name of the college was spelt "Maudleyn" as it was pronounced. Although the standard pronunciation of the name "Magdalene" in the English language has changed, the customary pronunciation of the college's name was retained.[6]

With the development of the General Post Office during the 19th century, the spelling of the college's name was fixed as "Magdalene" with a final "e", to avoid confusion with Magdalen College, Oxford.[6] The two colleges are pronounced the same.

College grace

| Latin | English | |

|---|---|---|

| Ante Prandium (before dinner) |

Benedic Domine nobis et donis tuis quae de tua largitate sumus sumpturi, et concede ut illis salubriter nutriti tibi debitum obsequium praestare valeamus, per Jesum Christum Dominum et Servatorem Nostrum, Amen. (response – Amen) | 'Bless us Lord and your gifts, which from your bounty we are about to receive, and grant that we, healthfully sustained by them, may render to you our dutiful service, through Jesus Christ, our Lord and Saviour (response – Amen)' |

| Post Prandium (after dinner) |

Laus Deo (response - Deo Gratias) | Praise to God (response – Thanks be to God) |

May Ball

The College's famous May Ball had been a biennial fixture since 1911.

People associated with Magdalene

Masters

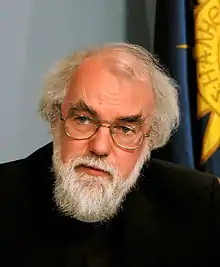

Master of Magdalene College is the title given to the Head of House. Rowan Williams, former Archbishop of Canterbury (2002–12) became the Master on 1 January 2013.[55] Sir Christopher John Greenwood succeeded Rowan Williams as master of Magdalene on 1 October 2020.

Power to appoint the Master was vested until 2012 in the Visitor of the College. Following an amendment to the College Statutes which was approved by the Queen in Council in February 2012, the Master is now appointed by the Governing Body of the College. The Master usually serves until reaching the statutory fellowship retirement age of 67. Exceptionally, this period may be extended until the Master in question reaches 70 as occurred in the case of Duncan Robinson, Master from 2002 to 2012.

With the position of Master comes College-based residency in the form of the Master's Lodge, which may be populated and decorated according to the wishes of the Master. Traditionally, every Sunday, the Master attends the service in the College Chapel before sitting at the head of the High Table in Hall for formal hall.

Notable current and past fellows

- Nicholas Boyle, Schroeder Professor of German and biographer of Goethe

- Howard Chase, Professor of Biochemical Engineering

- Tim Clutton-Brock, zoologist known particularly for his work on red deer and meerkats

- Helen Cooper, Professor of Medieval and Renaissance English, a Chair formerly held by three previous Magdalene fellows: C. S. Lewis, J. A. W. Bennett, and John Stevens

- Hannah Critchlow, Outreach Fellow, author, broadcaster and neuroscientist

- Saul Dubow, Smuts Professor of Commonwealth History

- Eamon Duffy, Professor of the History of Christianity and well known Roman Catholic commentator

- Richard Ellis, Professor of Astrophysics, University College London and former Director of Palomar Observatory, California

- Peter J. Grubb, ecologist and botanist

- John Gurdon, former Master, honorary fellow, developmental biologist, begetter of the Gurdon Institute, Nobel prizewinner in 2012

- C. S. Lewis, literary critic, author and theologian

- Derek Oulton, formerly Permanent Secretary, Lord Chancellor's Department

- I. A. Richards, English literary critic and rhetorician, considered one of the founders of the contemporary study of literature in English

- David Roberts (1911–82), architect and Director of Studies in Architecture, designer of more student housing in England than any other architect of his generation.

- Emma Rothschild, Jeremy and Jane Knowles Professor of History at Harvard University, director of the Centre for History and Economics

Notable alumni

Greg Clark, politician

Greg Clark, politician Stella Creasy, politician

Stella Creasy, politician Monty Don, television presenter and writer

Monty Don, television presenter and writer Charles Kingsley, author and academic

Charles Kingsley, author and academic John McPhee, award-winning writer

John McPhee, award-winning writer Samuel Pepys, naval administrator, politician and diarist

Samuel Pepys, naval administrator, politician and diarist Sir Michael Redgrave, actor

Sir Michael Redgrave, actor John Simpson, journalist

John Simpson, journalist.jpg.webp) Julian Fellowes, screenwriter

Julian Fellowes, screenwriter

Notable honorary fellows

References

- University of Cambridge (6 March 2019). "Notice by the Editor". Cambridge University Reporter. 149 (Special No 5): 1. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- "College History, The Early Days". Madgalene College website. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- "College History, Tudor Times". Madgalene College website. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 8 March 2009.

- "Magdalene College". Retrieved 17 August 2020.

- "Reports and Accounts for the year ended 30 June 2017" (PDF). Magdalene College, Cambridge. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "Why "Maudlyn"?". Magdalene College. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "Magdalene College, Cambridge". Cambridge Online. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Else, David; Berry, Oliver (2005). Great Britain. Lonely Planet. p. 454. ISBN 1-74059-921-7.

- Page, William, ed. (1906), "Houses of Benedictine monks: The abbey of Crowland", A History of the County of Lincoln: Volume 2, British History Online, pp. 105–18, retrieved 27 November 2008

- "Tudor Times". Magdalene College. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "The colleges and halls: Magdalene." A History of the County of Cambridge and the Isle of Ely: Volume 3, the City and University of Cambridge. Ed. J P C Roach. London: Victoria County History, 1959. 450-456. British History Online. Web. 29 April 2020. http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/cambs/vol3/pp450-456.

- "Oxford's and Worcester's Men And the "Boar's Head"". Archived from the original on 21 February 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "High Finance and Low Cunning". Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- Case of the Master and Fellows of Magdalene College - The Oxford Authorship Site. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- Trease, Geoffrey (1972). Samuel Pepys and his world. Norwich, Great Britain: Jorrold and Son.

- Knighton, C.S. (2004). Pepys, Samuel (1633–1703). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- The colleges and halls - Magdalene - British History Online. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- "The Pepys Library". Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 2 March 2000. Retrieved 10 June 2010.

- "Waterland, Daniel (WTRT699D)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Eighteenth-century: Enlightenment". Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "Edward Waring (WRN753E)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Peter Peckard: Biography and bibliography". Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "Cohen, Arthur (CHN849A)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Victorian Magdalene". Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 1 March 2004. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- "Benson, Arthur Christopher (BN881AC)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- "Twentieth Century". Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 1 March 2004. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

- O'Grady, Jane (13 June 2003). "Obituary - Professor Sir Bernard Williams". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 8 May 2009.

- "Magdalene in the Twenty-First Century". Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 30 March 2010.

- "Does university elitism still exist?". BBC News. 4 November 2001. Retrieved 31 March 2010.

- Alternative Prospectus. Magdalene College JCR. 2009.

- "Wong Yan Lung". GovHK. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- Cunich, Peter; Hoyle, David; Duffy, Eamon; Hyam, Ronald (1994). A History of Magdalene College Cambridge, 1428–1988. Cambridge: Magdalene College Publications. ISBN 0-9523073-0-8.

- Hyam, R. (1982). Magdalene Described. Sawston, Cambridgeshire, U.K.: Crampton & Sons Ltd.

- "Magdalene College: Chesterton Road: Cripps Court". Cambridge 2000. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- College Layout (Map). Magdalene College. 2009. Archived from the original on 12 January 2011.

- "First Court Restoration". Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 9 May 2011. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- The Chapel. Cambridge: Magdalene College. 2010.

- Holmes, Stephen Mark (2015). Sacred Signs in Reformation Scotland: Interpreting Worship, 1488–1590. London: Oxford University Press. p. 122. ISBN 9780191068744.

- "Magdalene College Cambridge Chapel New Organ". Goetze & Gwynn. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- Julian Cable (28 April 2011). "Cambridge College Latin Graces and Related Dining Customs". Cambridge University Heraldic & Genealogical Society. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- Magdalene College - A Brief Tour Guide. Cambridge: Magdalene College. 2010.

- Licence, Tom (2010). A history of the Fellows' Garden, Magdalene College. Cambridge: Magdalene College.

- "Back A New Library for Magdalene". Magdalene College. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "New Library at Magdalene College by Níall McLaughlin Architects breaks ground". Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- "Magdalene College, Cambridge". Parks & Gardens. The Hestercombe Gardens Trust. 16 November 2020.

- "Undergraduate Admissions: Magdalene College". University of Cambridge website. Retrieved 8 October 2011.

- Hartley, Paul (27 June 2010). "Review of the Year". President's Perspective. Cambridge: Magdalene College JCR. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - Butler, A. S. G. (1950). The architecture of Sir Edwin Lutyens. II. p. 50.

- Undergraduate Students Handbook. Cambridge: Magdalene College. 2009.

- "Climbing Mount Everest is work for supermen". New York Times. 18 March 1923.

- "Quayside". Cambridge 2000. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "Magdalene College:Chesterton Road:Cripps Court". Cambridge 2000. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "The Sir Humphrey Cripps Theatre". Cambridge: Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "Conferences - Meeting Rooms". Cambridge: Magdalene College. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- "Archbishop of Canterbury – Archbishop to be Master of Magdalene". Archbishop of Canterbury. Retrieved 14 September 2014.

Further reading

- Cunich, Hoyle, Duffy, and Hyam (1994). A History of Magdalene College Cambridge, 1428-1988. Cambridge: Crampton & Sons. ISBN 978-0952307303.

- Hyam, Ronald (2011). Magdalene Described: A Guide to the Buildings of Magdalene College Cambridge, 2nd edition. Cambridge: Magdalene College Publications.

- Hughes, M. E. J. (2015). The Pepys Library: And the Historic Collections of Magdalene College Cambridge. London: Scala. ISBN 978-1-85759-953-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Magdalene College, Cambridge. |