Mallee emu-wren

The mallee emu-wren (Stipiturus mallee) is a species of bird in the Australasian wren family, Maluridae. It is endemic to Australia.

| Mallee emu-wren | |

|---|---|

_(8079650268).jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Maluridae |

| Genus: | Stipiturus |

| Species: | S. mallee |

| Binomial name | |

| Stipiturus mallee Campbell, 1908 | |

| |

| Distribution of the mallee emu-wren | |

Its natural habitat is temperate grassland. It is threatened because of habitat loss.

Taxonomy and systematics

The mallee emu-wren is one of three species of the genus Stipiturus, commonly known as emu-wrens. It was first described in 1908 by Archibald James Campbell, and has been considered a subspecies of both of the other two species; with anywhere from one to three species recognised in total. No subspecies are recognised.[2] The common name of the genus is derived from the resemblance of their tails to the feathers of an emu.[3]

Description

The mallee emu-wren is an average 16.5 centimetres (6.5 inches) from head to tail.[4] The adult male mallee emu-wren has olive-brown upperparts with dark streaks, and a pale rufous unstreaked crown, and grey-brown wings. It has a sky blue throat, upper chest, lores, and ear coverts. The lores and ear coverts are streaked with black, and there is white streaking under the eye. Though still long, the tail is not as long as in other emu-wrens, and is composed of six filamentous feathers, the central two of which are longer than the lateral ones. The underparts are pale brown. The bill is black, and the feet and eyes are brown. The female resembles the male but lacks blue plumage. Its crown is paler red and it has white lores. Its bill is dark brown. The mallee emu-wren moults yearly after breeding, and birds have only the one plumage. The most recognizable and identifiable feature is the six emu-like feathers on its tail. This feature is highly distinguishable from other species found in its home range.[4]

Distribution and habitat

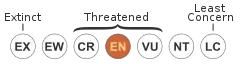

The mallee emu-wren is restricted to open mallee woodland with spinifex understory in north-western Victoria and south-eastern South Australia. This region is rich in Triodia or as it is commonly known spinifex. The spinifex grass often grows to 1 metre (3 feet 3 inches) in height and provides the optimal habitat for the mallee emu-wren.[5] Formerly classified as a vulnerable species by the IUCN, recent research shows that its numbers are decreasing more and more rapidly. It is consequently uplisted to endangered status in 2008. The mallee emu-wren is listed as nationally endangered under the Australian Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999. The current estimated total population size is approximately 4,000 birds. Although this species is widely dispersed throughout the Murray Sunset Reserve its home ranges are patchy throughout the 488 square kilometres (188 square miles) reserve.[6] Recent studies have concluded that the species is more widespread than previously thought. However, the species is much rarer in the southern regions of the preserve.[6] Their dispersion is heavily connected to the prevalence of hummocks formed by grass like plants of the genus Triodia. This biotic factor is of the most influence in the dispersion of mallee emu-wren.[6]

Behaviour and ecology

Like all emu-wrens, the mallee emu-wren is difficult to observe in clumps of spinifex. The mallee emu-wren is not a proficient flier.[7] The mallee emu-wren's diet consists mainly of insects including beetles, seeds, and some vegetation.[8]

Breeding

Breeding is little known, but has been recorded between September and November. The nest is a dome shaped structure built of grasses generally located deep within a clump of spinifex. Two or three oval eggs are laid which measure 13.5 to 16 mm (0.53–0.63 in) by 10 to 12 mm (0.39–0.47 in). They are white with reddish-brown freckles, more concentrated over the larger end.[2]

Threats

Too frequent burning

The vegetation varies in composition from year to year post controlled burn. As the vegetation reaches 30 years from the last burn it is no longer suitable for the mallee emu-wren. The strongest population numbers occur in regions that are less than 16 years old since their last burn.[6] Although the periodic burning is good for the mallee emu-wren the frequent wildfires or excessive controlled burns are detrimental.[6]

Climate fluctuations

The two main climate aspects that relate to the mallee emu-wren's mating success are temperature and rainfall. The current analysis of bioclimatic data supports the theory that a 1 degree Celsius change (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit change) in the average temperature would result in a greater than 90% contraction of the mallee emu-wren's population dispersion.[9] This poses a major issue for the survival of the mallee emu-wren because current data shows that since 1997 the Murray Region has had consecutive annual average temperatures that exceed the statistical average yearly temperatures.

Land uses

The current clearing and burning of land creates isolated ecological regions. This isolation of the populations has been detrimental the total population size. Agricultural uses that include grazing animals have decreased the density of grasses in the region. This clearing of the vegetation covering has been detrimental to the mallee emu-wren's habitat. The low lying grass provides the mallee emu-wren with its habitat and food sources.

Conservation

Surveys have been conducted at Billiatt Conservation Park and Ngarkat Conservation Park in South Australia (Clarke 2004; Gates 2003), and at Murray-Sunset National Park, Big Desert Wilderness Park, Big Desert State Forest, Wyperfeld National Park, Wathe Flora and Fauna Reserve and Bronzewing Flora and Fauna Reserve (Clarke 2007), and around Nowingi (Smales et al. 2005), in Victoria. The conservation status of the species has been re-assessed (Mustoe 2006). The habitat of the species has been modeled (Clarke 2005a). Information on the role and impact of fire in habitats occupied by mallee emu-wren has been summarised (Silveira 1993). A national recovery plan (Baker-Gabb in prep.) is being prepared, and a regional recovery plan is already in place (Clarke 2005; SA DEH 2006). An updated Flora and Fauna Guarantee Action Statement have been drafted for the species in Victoria (DSE 2007).

Bushfires in the Ngarkat Conservation Park in 2014 rendered the mallee emu-wren "functionally extinct" in South Australia, but initial reintroductions of captive-bred birds from Victoria have shown signs of success.[10][11]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Stipiturus mallee". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22703776A93936298. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22703776A93936298.en.

- Rowley, Ian; Russell, Eleanor M. (1997). Fairy-wrens and Grasswrens: Maluridae. Oxford University Press. p. 208. ISBN 9780198546900.

- Wade P., ed. (1977). Every Australian Bird Illustrated. Rigby. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-7270-0009-5.

- Higgins et al. 2001

- Howe, F. E. (1933-04-01). "The Mallee Emu-Wren (Stipiturus mallee)". Emu - Austral Ornithology. 32 (4): 266–269. doi:10.1071/MU932266. ISSN 0158-4197.

- Brown, Sarah; Clarke, Michael; Clarke, Rohan (2009-02-01). "Fire is a key element in the landscape-scale habitat requirements and global population status of a threatened bird: The Mallee Emu-wren (Stipiturus mallee)". Biological Conservation. 142 (2): 432–445. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2008.11.005. ISSN 0006-3207.

- "Department of the Environment and Energy". Department of the Environment and Energy. Retrieved 2018-01-07.

- Schodde, Richard (1982). The Fairy-wrens. A Monograph of the Maluridae. Melbourne: Landsdowne Editions. ISBN 978-0701810511.

- "Enhanced greenhouse climate change and its potential effect on selected fauna of south-eastern Australia: A trend analysis - ScienceBase-Catalog". www.sciencebase.gov. Retrieved 2018-01-07.

- Rescue plan underway for Mallee emu-wren after bushfires destroy natural habitat ABC News, 7 September 2017. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- 'Tenacious' Mallee emu-wren breeding itself from South Australian extinction ABC News, 8 December 2018. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

Cited text

- P.J. Higgins, J.M. Peter and W.K. Steele, Editors, Handbook of Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic Birds vol. 5, Oxford University Press, Melbourne (2001).

- H.R. Pulliam and B.J. Danielson, Sources, sinks and habitat selection: a landscape perspective on population dynamics, The American Naturalist 137 (1991), pp. S50–S66.

- R. Schodde, The bird fauna of the mallee – its biogeography and future. In: J.C. Noble, P.J. Joss and G.K. Jones, Editors, The Mallee Lands. A Conservation Perspective, CSIRO, Australia (1990), pp. 61–70.