Manchester Art Gallery

Manchester Art Gallery, formerly Manchester City Art Gallery, is a publicly owned art museum on Mosley Street in Manchester city centre. The main gallery premises were built for a learned society in 1823 and today its collection occupies three connected buildings, two of which were designed by Sir Charles Barry. Both Barry's buildings are listed. The building that links them was designed by Hopkins Architects following an architectural design competition managed by RIBA Competitions. It opened in 2002 following a major renovation and expansion project undertaken by the art gallery.

| |

| Established | 1823 |

|---|---|

| Location | Mosley Street, Manchester, England |

| Coordinates | 53°28′43″N 2°14′29″W |

| Collection size | approx. 25,000 objects[1] |

| Visitors | 514,852 (1 April 2013 – 31 March 2014)[2] |

| Public transit access | Metrolink: St Peter's Square and Piccadilly Gardens stations |

| Website | manchesterartgallery.org |

| Size | 807,000 sq ft (75,000 m2) in 94 Galleries |

Manchester Art Gallery is free to enter and open seven days a week. It houses many works of local and international significance and has a collection of more than 25,000 objects. More than half a million people visited the museum in the period of a year, according to figures released in April 2014.

History

Royal Manchester Institution

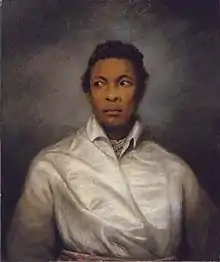

The Royal Manchester Institution was a scholarly society formed in 1823.[3] It was housed in what is now the art gallery's main gallery building on Mosley Street. The first object acquired for its collection, James Northcote's A Moor (a portrait of the celebrated black actor Ira Aldridge), was bought in 1827.[3]

The Royal Manchester Institution opened its galleries to the public ten years after its formation and subsequently held regular art exhibitions, collected works of fine art and promoted the arts from the 1820s until 1882 when its premises and collections were transferred under Act of Parliament to Manchester Corporation, becoming Manchester Art Gallery.[3] The institution was handed over on condition that £2000 per annum would be spent on art for the next 20 years.[3] The Art Gallery Committee bought enthusiastically and by the end of the 19th century had accrued an impressive collection of fine art, added to by gifts and bequests from wealthy Mancunian industrialists.

On 3 April 1913 the gallery was attacked by Lillian Williamson, Evelyn Manesta and another suffragette, Annie Briggs. The three attacked the glass of thirteen paintings including two by Millais and two by George Frederick Watts. Four of the paintings were damaged by the broken glass. Williamson was sent to jail for three months and Manesta for one.[4]

Governance

The gallery is operated by Manchester City Galleries, a department of Manchester City Council which is also responsible for Platt Hall Platt Hall, Fallowfield. Alistair Hudson is the director of the galleries and also director of the University of Manchester's Whitworth Art Gallery. He became joint director in a collaboration between the council and the university in 2018.[5]

The gallery's budget is controlled by the council but it also funded by the Manchester Art Gallery Trust, a charity (Registered Charity Number 1048581) that supports its work. The trust raises nearly half the funding required from companies, individuals and grant making trusts and foundations.[6] The gallery is currently open daily and on the first Wednesday of every month opens until 9pm.[7]

Architecture

Manchester Art Gallery is housed in three connected buildings. The City Art Gallery building, which faces onto Mosley Street, was designed and constructed between 1824–35. It originally housed the Royal Manchester Institution. Designed by architect Sir Charles Barry in the Greek Ionic style, the building is now Grade I listed. The two-storey gallery is built in rusticated ashlar to a rectangular plan on a raised plinth. The roof is hidden by a continuous dentilled cornice and plain parapet. Its eleven-bay facade has two three-bay side ranges and a central five-bay pedimented projecting portico with six Ionic columns. Set back behind the parapet is an attic with small windows that forms a lantern above the entrance hall.[8]

Manchester Athenaeum, also designed by Barry, was built in 1837 and was bought by the Manchester Corporation in 1938 to provide additional space. It is Grade II* listed and designed in the Italian Palazzo style.[9] The Athenaeum fronts onto Princess Street.

In November 1994 an architectural design competition managed by RIBA Competitions was launched to refurbish the existing historic gallery and the Athenaeum and link them with a new building on the car park site.[10] The competition attracted 132 architects, six of whom were selected to proceed to the final stage. Michael Hopkins and Partners were announced as winners in January 1995.[10] The gallery closed in 1998 and reopened in 2002 following the £35 million refurbishment and extension.[10][11] The new extension was criticised as "the splendid and really beautiful interiors of the original building .. have been gratuitously spoiled", and was the 2002 winner of the Sir Hugh Casson Award

Collections

The gallery has fine art collection consisting of more than 2,000 oil paintings, 3,000 watercolours and drawings, 250 sculptures, 90 miniatures and around 1,000 prints.[12] It owns more than 13,000 decorative art objects including ceramics, glass, enamels, furniture, metalwork, arms and armour, wallpapers, dolls houses and related items.[13] The oldest object is an Egyptian canopic jar from circa 1100 BC.[13]

Thomas Coglan Horsfall's eclectic collection from the Manchester Art Museum in Ancoats Hall was absorbed into the gallery when the museum closed in 1953.[14]

Manchester Art Gallery is strongest in its collection of Victorian art, especially that of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, and Victorian decorative arts.

The gallery houses several works by the French impressionist, Pierre Adolphe Valette, who painted and taught in Manchester in the early years of the 20th century; some of his scenes of foggy Manchester streets and canals are displayed. A Cézanne hangs in the same room, showing the similarity in treatment and subject between his misty French river bridge and Valette's bridge in a pre-Clean Air Act Mancunian fog. L. S. Lowry was one of Valette's students and the influence on Lowry of impressionism can be seen at the gallery, where paintings by the two artists hang together. The museum houses The Picnic (1908), a work by the British Impressionist painter Wynford Dewhurst, who was born in Manchester. Annie Swynnerton who was born in Hulme is represented in the collection by 16 paintings and her contemporary at the Manchester School of Art, Susan Dacre by 17 paintings.[15]

As well as paintings the museum holds collections of glass, silverware and furniture, including four pieces by the Victorian architect and designer William Burges.[16]

Controversy

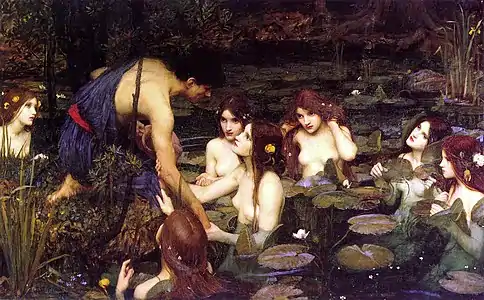

In January 2018, the gallery took down John William Waterhouse's Hylas and the Nymphs (1896), leaving an empty space to encourage debate as to how women's bodies should be displayed. Post-it notes were provided for visitors to air their views. The galley's actions prompted a strong backlash with accusations of censorship, puritanism and political correctness. The museum was "completely taken by surprise by the ferocity of the response"[17] and the painting was rehung after a week's absence.[18]

The removal came two months after an unsuccessful campaign to have the Metropolitan Museum of Art remove a painting by Balthus of an adolescent girl.[19]

Highlights of collection

.jpg.webp) The Scapegoat, 1854–55, William Holman Hunt

The Scapegoat, 1854–55, William Holman Hunt Work, 1865, Ford Madox Brown

Work, 1865, Ford Madox Brown

Artists

Dutch School

- Backhuysen, Ludolf – 1 painting;

- Borch, Gerard ter – 2 paintings;

- Brekelenkam, Quirijn van – 2 paintings;

- Jan van de Cappelle – 3 paintings;

- Cuyp, Aelbert – 2 paintings;

- Dou, Gerrit – 1 painting;

- Heem, Jan Janszoon de – 1 painting;

- Hobbema, Meyndert – 1 painting;

- Hooch, Pieter de – 2 paintings;

- Ochtervelt, Jacob – 2 paintings;

- Ostade, Adriaen van – 1 painting;

- Ruysdael, Salomon van – 2 paintings;

- Snyders, Frans – 1 painting;

- Sorgh, Hendrik Martenszoon – 2 paintings;

- Steen, Jan – 1 painting;

- Velde, Adriaen van de – 1 painting;

- Velde the Younger, Willem van de – 2 paintings;

English School

- Beechey, William – 2 paintings;

- Burra, Edward – 1 painting;

- Constable, John – 1 painting;

- Gainsborough, Thomas – 10 paintings;

- Hogarth, William – 2 paintings;

- Kneller, Sir Godfrey – 1 paintings;

- Landseer, Sir Edwin – 3 paintings;

- Lawrence, Thomas – 1 painting;

- Lely, Peter – 1 painting;

- Lowry, L. S. – 4 paintings;

- Nevinson, C. R. W. – 1 painting;

- Reynolds, Joshua – 4 paintings;

- Souch, John – 1 painting;

- Stubbs, George – 1 paintings;

- Turner, J. M. W. – 1 painting;

- Valette, Pierre Adolphe – 5 paintings;

Flemish School

- Francken the Younger, Frans – 1 painting;

- Teniers the Younger, David – 3 paintings;

French School

- Corot, Jean-Baptiste-Camille – 2 paintings;

- Degas, Edgar – 1 painting;

- Dughet, Gaspard – 1 painting;

- Gauguin, Eugène Henri Paul – 1 painting;

- Gellée, Claude – 1 painting;

- Mengin, Charles – 1 painting;

- Pissarro, Camille – 1 painting;

- Renoir, Pierre Auguste – 1 painting;

- Vernet, Claude-Joseph – 1 painting;

German School

- Zoffany, Johan – 1 painting;

Italian School

- Daddi, Bernardo – 1 painting;

- Giordano, Luca – 1 painting;

- Mura, Francesco de – 1 painting;

- Reni, Guido – 1 painting;

- Turchi, Alessandro – 1 painting;

- Zuccarelli, Francesco – 1 painting;

- Giovanni Ansaldo – 1 painting

Hungarian School

- Wagner, Alexander von – 1 painting

Temporary exhibitions

2013: Raqib Shaw

See also

References

- "About the collection". Manchester Galleries. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- Denise Evans (11 April 2014). "Half a million visit Manchester Art Gallery in a year". Manchester Evening News. Retrieved 12 January 2015.

- History of the collection, Manchester Galleries, retrieved 13 January 2015

- "Manchester Art Gallery Outrage | Manchester Art Gallery". Manchester Art Gallery. 8 March 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2018.

- Rebecca Atkinson (25 February 2011), Balshaw named joint director of Whitworth and Manchester Art Gallery, Museums Association, retrieved 13 January 2015

- Supporting Us, Manchester Galleries, retrieved 13 January 2015

- Jonathan Schofield (11 April 2014). "Art gallery's record year tells us about Manchester tourism". Manchester Confidential. Archived from the original on 13 January 2015. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- Historic England, "City Art Gallery (1282980)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 1 May 2012

- Historic England, "The Athenaeum 81 Princess Street (1270889)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 28 January 2015

- Manchester Art Gallery Expansion Project, Manchester Galleries, retrieved 13 January 2015

- Manchester Art Gallery, Royal Institute of British Architects, retrieved 1 May 2012

- Fine art, Manchester Galleries, retrieved 13 January 2015

- Decorative art, Manchester Galleries, retrieved 13 January 2015

- Stuart Eagles. "Thomas Coglan Horsfall, and Manchester Art Museum and University Settlement". infed.org. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- "We found 2,132 paintings relevant to your search". The BBC. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2015.

- "Search the Collections". Manchester Art Gallery. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- Higgins, Charlotte (19 March 2018). "'The vitriol was really unhealthy': artist Sonia Boyce on the row over taking down Hylas and the Nymphs". the Guardian. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- Victorian nymphs painting back on display after censorship row, The BBC, retrieved 3 February 2018

- Libbey, Peter (4 December 2017). "Met Defends Suggesting Painting of Girl After Petition Calls for its Removal". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 February 2018.