Marillion

Marillion /məˈrɪliən/ are a British rock band, formed in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, in 1979. They emerged from the post-punk music scene in Britain and existed as a bridge between the styles of punk rock and classic progressive rock,[5] becoming the premier neo-progressive rock band of the 1980s.[6]

Marillion | |

|---|---|

Marillion, 2009. L-R: Ian Mosley, Pete Trewavas, Steve Hogarth, Mark Kelly, and Steve Rothery. | |

| Background information | |

| Origin | Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Genres | |

| Years active | 1979–present |

| Labels | EMI, Capitol, Castle, Racket, Intact, IRS, Caroline, Sanctuary, Velvel/Koch, Edel, Liberty, Pony Canyon |

| Website | www |

| Members | Steve Rothery Mark Kelly Pete Trewavas Ian Mosley Steve Hogarth |

| Past members | Mick Pointer Brian Jelliman Doug Irvine Fish Diz Minnitt Andy Ward John 'Martyr' Marter Jonathan Mover |

Marillion's recorded studio output since 1982 is composed of nineteen albums, generally regarded in two distinct eras, delineated by the departure of original lead singer Fish in late 1988 and the subsequent arrival of replacement Steve Hogarth in early 1989. The band achieved eight Top Ten UK albums between 1983 and 1994, including a number one album in 1985 with Misplaced Childhood, and during the period the band were fronted by Fish they had eleven Top 40 hits on the UK Singles Chart. They are best known for the 1985 singles "Kayleigh" and "Lavender", which reached number two and number five respectively, with "Kayleigh" also entering the Billboard Hot 100 in the United States.

Marillion's first album released with Hogarth, 1989's Seasons End, was another Top Ten hit, and albums continued to chart well until their departure from EMI Records following the release of their 1996 live album Made Again and the dissipation of the band's mainstream popularity in the late 1990s; save for a resurgence in the mid- to late-2000s,[7] they have essentially been a cult act since then.[8] Marillion have achieved a further twelve Top 40 hit singles in the UK with Hogarth, including 2004's "You're Gone", which charted at No. 7 and is the biggest hit of his tenure. The band continue to tour internationally, becoming ranked 38th in Classic Rock's "50 Best Live Acts of All Time" in 2008.[9] In 2016, they returned to the UK Albums Chart Top Ten for the first time in 22 years with their highest chart placing since 1987.[10]

Despite unpopularity in the mainstream media and a consistently unfashionable status within the British music industry, Marillion have maintained a very loyal international fanbase, becoming widely acknowledged as playing a pioneering role in the development of crowdfunding and fan-funded music. They have sold over 15 million albums worldwide.[11]

History

Formation and early years (1978–1982)

—Fish on his first impression of the band[12]

In 1977, Mick Pointer joined Electric Gypsy, which also included Doug Irvine on bass. Pointer and Irvine left to form their own band, Silmarillion, after J.R.R. Tolkien's book The Silmarillion, in late 1978. They played one London show as an instrumental band with Neal Cockle (keys) and Martin Jenner (guitar). 1979 saw a new line-up of Mick Pointer, Steve Rothery, Doug Irvine and Brian Jelliman. They played their first concert at Berkhamsted Civic Centre, Hertfordshire, on 1 March 1980.[13] According to Pointer, it was at this stage that the name was shortened to Marillion.[14][15][16]

Other sources have that the band name was shortened to Marillion in 1981 to avoid potential copyright conflicts,[17] at the same time as Fish and bassist William 'Diz' Minnitt[18] replaced original bassist/vocalist Doug Irvine following an audition at Leyland Farm Studios in Buckinghamshire on 2 January 1981. Rothery, drummer Mick Pointer, and keyboardist Brian Jelliman completed this line-up; the first gig with this line-up was at the Red Lion Pub[19] at 35 Market Square in Bicester on 14 March 1981. Irvine eventually joined the band Steam Shed.[20] By the end of 1981, Kelly had replaced Jelliman, with Trewavas replacing Minnitt in 1982.[21] Minnitt later formed Pride of Passion[22] and went on to perform with Zealey and Moore.[23]

Marillion's first recordings were two demos recorded in March and the summer of 1980, prior to Fish and Minnitt joining the band. Two versions of the Spring demo circulate amongst collectors; the first has four tracks; "The Haunting of Gill House", "Herne the Hunter", an untitled track known as "Scott's Porridge", and "Alice". The second version has an instrumental version of "Alice" in place of "Scott's Porridge". All tracks are instrumental apart from "Alice", with vocals by Doug Irvine. The summer demo has three tracks; "Close" (parts of which were later rewritten into "The Web", "He Knows You Know" and "Chelsea Monday"), "Lady Fantasy" (an original based on an earlier Electric Gypsy song), and another version of "Alice". Both were recorded at The Enid's studio in Hertfordshire. Following Irvine's departure and replacement by Fish and Minnitt, the band recorded another demo tape, produced by Les Payne, in July 1981 that included early versions of "He Knows You Know", "Garden Party", and "Charting the Single".

The group attracted attention with a three-track session for the Friday Rock Show (early versions of "The Web", "Three Boats Down from The Candy", and "Forgotten Sons"). They were subsequently signed by EMI Records. They released their first single, "Market Square Heroes", in 1982, with the epic song "Grendel" on the B-side of the 12" version. Following the single, the band released their first full-length album in 1983.

Script for a Jester's Tear and Fugazi (1983–1984)

The music on their debut album, Script for a Jester's Tear, was born out of the intensive performances of the previous years. Although it had some progressive rock stylings, it also had a darker edge. The album was a commercial success, peaking at number seven on the UK album chart and producing the singles "He Knows You Know" (number 35) and "Garden Party" (number 16).[24] Although they were accused of being Genesis soundalikes,[25] the album reached the Platinum certification and has been credited with giving a second life to progressive rock bands from the previous era.[25]

Following the UK tour to promote Script for a Jester's Tear, Mick Pointer was dismissed due to Fish's dissatisfaction with what he later described as the drummer's "awful" timing and failure to develop as a musician with the rest of the band.[26] Ian Mosley, who had played for acts including Darryl Way's Wolf and the Gordon Giltrap band, was eventually secured as Pointer's replacement after a series of other drummers, including Andy Ward and Jonathan Mover, were short-lived.[27] Despite the numerous production problems encountered during this period, the second album, Fugazi, built upon the success of the first album with a more streamlined hard rock sound.[28] It improved on the chart placing of its predecessor by reaching the top five and produced the singles "Punch and Judy" (number 29) and "Assassing" (number 22).[24]

In November 1984, Marillion then released their first live album, Real to Reel, featuring songs from Fugazi and Script for a Jester's Tear, as well as "Cinderella Search" (B-side to 'Assassing') and the debut single "Market Square Heroes", which had not been available on album until that point. The album entered the UK album charts at No. 8.

Misplaced Childhood and international success (1985–1986)

Their third and commercially most successful studio album was Misplaced Childhood, which had a more mainstream sound. The lead single from the album, "Kayleigh", received major promotion by EMI and gained heavy rotation on BBC Radio 1 and Independent Local Radio stations as well as television appearances, bringing the band to the attention of a much wider audience. "Kayleigh" reached number two in the UK and "Lavender" reached number five; these remain the only singles by the band to enter the top five.[24]

Following the exposure given to "Kayleigh" and its subsequent chart success, the album became their only number one in the UK, knocking Bryan Ferry's Boys and Girls off the top spot and holding off a challenge from Sting, whose first solo album, The Dream of the Blue Turtles, entered the chart in the same week.[29][30] The third single from the album, "Heart of Lothian", became another top-thirty hit for the band, reaching No. 29. The album came sixth in Kerrang! magazine's "Albums of the Year" in 1985.[31] "Kayleigh" also gave Marillion its sole entry on the Billboard Hot 100, reaching No. 74. In the summer of 1986, the band played to their biggest ever audience as special guests to Queen at a festival in Germany attended by a crowd of over 150,000 people.[32] They were also offered the Highlander soundtrack but turned it down because of their world tour, a missed opportunity which Rothery later said he regretted.[33]

Clutching at Straws and the departure of Fish (1987–1988)

The fourth studio album, Clutching at Straws, shed some of its predecessor's pop stylings and retreated into a darker exploration of excess, alcoholism, and life on the road, representing the strains of constant touring that would result in the departure of Fish to pursue a solo career. It did continue the group's commercial success, however; lead single "Incommunicado" charted at No. 6 in the UK charts gaining the band an appearance on Top of the Pops, and the album entered the UK album chart at No. 2, Marillion's second highest placing. "Sugar Mice" and "Warm Wet Circles" also became hit singles, both reaching No. 22. Fish has also stated in interviews since that he believes this was the best album he made with the band.[34] The album came sixth in Kerrang! magazine's "Albums of the Year" in 1987, equalling the ranking given to Misplaced Childhood. It was also included in Q magazine's "50 Best Recordings of the Year".[35] Fish explained his reasons for leaving in an interview in 2003:

"By 1987 we were over-playing live because the manager was on 20 per cent of the gross. He was making a fantastic amount of money while we were working our asses off. Then I found a bit of paper proposing an American tour. At the end of the day the band would have needed a £14,000 loan from EMI as tour support to do it. That was when I knew that, if I stayed with the band, I'd probably end up a raging alcoholic and be found overdosed and dying in a big house in Oxford with Irish wolfhounds at the bottom of my bed."[36]

Fish gave the band a choice to continue with either him or the manager. They sided with the manager and Fish left for a solo career.[37] His last live performance with Marillion was at Craigtoun Country Park on 23 July 1988.[38] Due to lengthy legal battles, informal contact between Fish and the other four band members apparently did not resume until 1999. Fish would later disclose in the liner notes to the 2-CD reissue of Clutching at Straws that he and his former bandmates had met up and discussed the demise of the band and renewed their friendship, and had come to the consensus that an excessive touring schedule and too much pressure from the band's management led to the rift.

Although reportedly now on good personal terms, both camps had always made it very clear that the oft-speculated-upon reunion would never happen. However, when Fish headlined the 'Hobble on the Cobbles' free concert in Aylesbury's Market Square on 26 August 2007, the attraction of playing their debut single in its spiritual home proved strong enough to overcome any lingering bad feeling between the former band members, and Kelly, Mosley, Rothery, and Trewavas replaced Fish's backing band for an emotional encore of "Market Square Heroes".

In a press interview following the event, Fish denied this would lead to a full reunion, saying that: "Hogarth does a great job with the band. We forged different paths over the 19 years."[39]

Seasons End and Holidays in Eden (1989–1991)

After the split, the band found Steve Hogarth, the former keyboardist and sometime vocalist of The Europeans. Hogarth stepped into a difficult situation, as the group had already recorded some demos of the next studio album, which eventually would have become Seasons End. Hogarth was a significant contrast to Fish, coming from a new wave musical background instead of progressive rock. He had also never owned a Marillion album before joining the band.[40]

After Fish left the group (taking his lyrics with him), Hogarth set to work crafting new lyrics to existing songs with lyricist and author John Helmer. The demo sessions of the songs from Seasons End with Fish vocals and lyrics can be found on the bonus disc of the remastered version of Clutching at Straws, while the lyrics found their way into various Fish solo albums such as his first solo album, Vigil in a Wilderness of Mirrors, some snippets on his second, Internal Exile and even a line or two found its way to his third album, Suits.

Hogarth's second album with the band, Holidays in Eden, was the first he wrote in partnership with them and includes the song "Dry Land", which Hogarth had written and recorded in his earlier duo, How We Live. As quoted from Steve Hogarth, "Holidays in Eden was to become Marillion's "pop"est album ever, and was greeted with delight by many, and dismay by some of the hardcore fans".[41] Despite its pop stylings, the album failed to cross over beyond the band's existing fanbase and produced no major hit singles.

Brave, Afraid of Sunlight and split with EMI Records (1992–1995)

Holidays in Eden was followed by Brave, a dark and richly complex concept album that took the band 18 months to release. The album also marked the start of the band's longtime relationship with producer Dave Meegan. An independent film based on the album, which featured the band, was also released.

The next album, Afraid of Sunlight, would be the band's last album with record label EMI Records. Once again, it received little promotion, no mainstream radio airplay and its sales were disappointing for the band. Despite this, it was one of their most critically acclaimed albums and was included in Q's 50 Best Albums of 1995.[42] One track of note on the album is Out of This World, a song about Donald Campbell, who died while trying to set a speed record on water. The song inspired an effort to recover both Campbell's body and the "Bluebird K7," the boat which Campbell crashed in, from the water.[43] The recovery was finally undertaken in 2001, and both Steve Hogarth and Steve Rothery were invited.[44] In 1998, Steve Hogarth said this was the best album he had made with the band.[45]

This Strange Engine, Radiation and marillion.com (1996–1999)

What followed was a string of albums and events that saw Marillion struggling to find their place in the music business. This Strange Engine was released in 1997 with little promotion from their new label Castle Records, and the band could not afford to make tour stops in the United States. Their dedicated US fan base decided to solve the problem by raising some $60,000 themselves online to give to the band to come to the US.[46] The band's loyal fanbase (combined with the Internet) would eventually become vital to their existence.

The band's tenth album Radiation saw them taking a different approach and was received by fans with mixed reactions.[47]

marillion.com was released the following year and showed some progression in the new direction. The band were still unhappy with their record label situation.

Anoraknophobia and Marbles (2000–2006)

The band decided that they would try a radical experiment by asking their fans if they would help fund the recording of the next album by pre-ordering it before recording even started. The result was over 12,000 pre-orders which raised enough money to record and release Anoraknophobia in 2001.[48] The band was able to strike a deal with EMI to also help distribute the album. This allowed Marillion to retain all the rights to their music while enjoying commercial distribution. By this time the band had also parted company with their long-time manager, saving 20 per cent of the band's income.

The success of Anoraknophobia allowed the band to start recording their next album, but they decided to leverage their fanbase once again to help raise money towards marketing and promotion of a new album. The band put up the album for pre-order in mid-production. This time fans responded by pre-ordering 18,000 copies.[49]

Marbles was released in 2004 with a 2-CD version that is only available at Marillion's website – a 'thank-you' gesture to the over 18,000 fans who pre-ordered it, and as even a further thanks to the fans, their names were credited in the sleeve notes (this 'thank you' to the fans also occurred with the previous album, Anoraknophobia).

The band's management organised the biggest promotional schedule since they had left EMI and Steve Hogarth secured interviews with prominent broadcasters on BBC Radio, including Matthew Wright, Bob Harris, Stuart Maconie, Simon Mayo and Mark Lawson. Marbles also became the band's most critically acclaimed album since Afraid of Sunlight, prompting many positive reviews in the press.[50][51][52][53][54][55][56] The band released "You're Gone" as the lead single from the album. Aware that it was unlikely to gain much mainstream radio airplay, the band released the single in three separate formats and encouraged fans to buy a copy of each to get the single into the UK Top Ten. The single reached No. 7, making it the first Marillion song to reach the UK Top Ten since "Incommunicado" in 1987 and the band's first Top 40 entry since "Beautiful" in 1995. The second single from the album, "Don't Hurt Yourself", reached No. 16. Following this, they released a download-only single, "The Damage (live)", recorded at the band's sell-out gig at the London Astoria. All of this succeeded in putting the band back in the public consciousness, making the campaign a success. Marillion continued to tour throughout 2005 playing several summer festivals and embarking on acoustic tours of both Europe and the United States, followed up by the "Not Quite Christmas Tour" of Europe throughout the end of 2005.

A new DVD, Colours and Sound, was released in Feb 2006, documenting the creation, promotion, release, and subsequent European tour in support of the album Marbles.

Somewhere Else and Happiness is the Road (2007–2008)

April 2007 saw Marillion release their fourteenth studio album Somewhere Else, their first album in 10 years to make the UK Top No. 30. The success of the album was further underscored by that of the download-only single "See it Like a Baby", making UK No. 45 (March 2007) and the traditional CD release of "Thankyou Whoever You Are / Most Toys", which made UK No. 15 and No. 6 in the Netherlands during June 2007.

In July 2008 the band posted a contest for fans to create a music video for the soon-to-be released single "Whatever is Wrong with You", and post it on YouTube. The winner would win £5,000.[57][58]

Happiness Is the Road, released in October 2008, again featured a pre-order "deluxe edition" with a list of the fans who bought in advance, and a more straightforward regular release. It is another double album, with one disc based on a concept and the second containing the other songs that aren't a part of the theme. Before the album's release, on 9 September 2008, Marillion pre-released their album via p2p networks themselves. Upon attempting to play the downloaded files, users were shown a video from the band explaining why they had taken this route. Downloaders were then able to opt to purchase the album at a user-defined price or select to receive DRM-free files for free, in exchange for an email address. The band explained that although they do not support piracy, they realised their music would inevitably be distributed online anyway, and wanted to attempt to engage with p2p users and make the best of the situation.[59]

Less is More and Sounds That Can't Be Made (2009–2014)

The band's sixteenth studio album (released 2 October 2009) was an acoustic album featuring new arrangements of previously released tracks (except one, the new track: "It's Not Your Fault") entitled Less Is More.

Their seventeenth studio album, titled Sounds That Can't Be Made, was released in September 2012. Two versions of the album were released: A 2-disc 'deluxe' version that included a DVD with 'making-of' features and sound-check recordings and a single CD jewel case version. The 'deluxe' version also included a 128-page book that incorporated lyrics, artwork and, as was the case with Anoraknophobia, Marbles and Happiness is the Road, the names of people who pre-ordered the album. Parts of the album were recorded at Peter Gabriel's Real World Studios in 2011.

Marillion were awarded "Band of the Year" at the annual Progressive Music Awards in 2013.[60]

Fuck Everyone and Run (F E A R) (2015–present)

The band announced in September 2015 that they were working on a new album, provisionally titled M18 and later confirmed as Fuck Everyone and Run (F E A R). As with several of their previous releases, the recording of the album was to be funded by fan pre-orders, this time through direct-to-fan website PledgeMusic. The album was released on 23 September 2016 [61][62] debuting at number 4 in the official UK charts of 30 September 2016, their highest placing since Clutching at Straws nearly three decades earlier. In November 2016, they announced their first ever show at the Royal Albert Hall in London, in October 2017.[63] The gig sold out in just 4 minutes and was filmed for DVD release. They also won "UK Band of the Year" at the 2017 Progressive Music Awards.[64] In March 2018, the film of the Royal Albert Hall gig was premiered at cinemas around the UK, before the DVD launch, with the band attending the showing in London. On 6 April the concert was released as All One Tonight - Live at the Royal Albert Hall.

In March 2018, Steve Hogarth was involved with fellow musician Howard Jones in helping to unveil a memorial to David Bowie, which is situated close to Aylesbury's Market Square.[65][66] The memorial was the inspiration of promoter David Stopps, who booked Bowie to appear at the Friars Aylesbury where he debuted Ziggy Stardust. The bulk of the funds for the memorial were raised at a gig held at the Waterside Theatre in Aylesbury on the evening of the unveiling which Marillion headlined, alongside Howard Jones, John Otway and the Dung Beatles, all of whom have close association to Aylesbury and in particular, the Friars.

Line-up, influences and sound changes

—Mark Kelly in 2016[67]

Marillion's music has changed stylistically throughout their career. The band themselves stated that each new album tends to represent a reaction to the preceding one, and for this reason their output is difficult to 'pigeonhole'. Although the band has featured two very distinct and different vocalists, the core instrumental line-up[68] of Steve Rothery (lead guitar, and the sole 'pre-Fish' original member), Pete Trewavas (bass), Mark Kelly (keyboards) and Ian Mosley (drums) has been unchanged since 1984.

Their 1980s sound (with Fish on vocals) was guitar and keyboard-led neo-progressive rock. They have been described at their outset as "a bridge between punk and classic progressive rock".[5] Guitarist Steve Rothery wrote most of the music during the period Fish was in the band.[69] Iron Maiden guitarist Janick Gers commented, "What I love so much about Marillion is that they could be very strong and powerful and have very quiet passages, but the powerful stuff was really edgy and heavy... I just thought he (Fish) wrote good lyrics, and they wrote good music, and it fit together effortlessly."[70]

They were often compared unfavourably by critics during the Fish era with the Peter Gabriel era of Genesis,[71] although the band had many other influences. Fish was influenced by a wide range of artists and his favourite albums were by artists such as Van der Graaf Generator, Joni Mitchell, the Who, Pink Floyd, John Martyn, Yes, Lowell George, Led Zeppelin, Roy Harper, the Faces, the Beatles and Supertramp.[72] Rothery's main influences were Jimi Hendrix, Carlos Santana, David Gilmour, Andrew Latimer of Camel, Steve Hackett, Jeff Beck and Joni Mitchell, with Gordon Giltrap also an early influence on the development of his playing style.[73] Kelly's biggest inspiration was Yes keyboardist Rick Wakeman,[74] and Trewavas' favourite bass player was Paul McCartney.[75] Original drummer Mick Pointer was a huge fan of Neil Peart's drumming in his favourite band, Rush.[76]

During the Steve Hogarth era, their sound has been compared, on various albums, to more contemporary acts such as U2,[77] Radiohead,[47][78] Coldplay,[78] Muse,[78] Talk Talk,[79] Elbow,[79] and Massive Attack.[79] In 2016, Hogarth himself was quoted as describing the band: "If Pink Floyd and Radiohead had a love child that was in touch with their feminine side, they would be us."[80] According to an interview with Rothery in 2016, many of their later albums with Hogarth had been written by jamming.[69]

In the media

—Keyboardist Mark Kelly[78]

The chief music critic of The Guardian, Alexis Petridis, has described Marillion as "perennially unfashionable prog-rockers".[81] On the subject of joining the band in 1989, Steve Hogarth said in a 2001 interview: "At about the same time, Matt Johnson of The The asked me to play piano on his tour. I always say I had to make a choice between the most hip band in the world, and the least." In the same conversation, he said: "We're just tired of the opinions of people who haven't heard anything we've done in ten years. A lot of what's spread about this band is laughable."[40]

Much of the band's enduring and unfashionable reputation stems from their emergence in the early 1980s as the most commercially successful band of the neo-progressive rock movement, an unexpected revival of the progressive rock musical style that had fallen out of critical favour in the mid-1970s. Some early critics were quick to dismiss the band as clones of Peter Gabriel-era Genesis due to musical similarities, such as their extended songs, a prominent and Mellotron-influenced keyboard sound, vivid and fantastical lyrics and the equally vivid and fantastical artwork by Mark Wilkinson used for the sleeves of their albums and singles. Lead singer Fish was also often compared with Gabriel due to his early vocal style and theatrical stage performances, which in the early years included wearing face paint.

As Jonh Wilde summarised in Melody Maker in 1989:

At the end of a strange year for pop music, Marillion appeared in November 1982 with "Market Square Heroes". There were many strange things about 1982, but Marillion were the strangest of them all. For six years, they stood out of time. Marillion were the unhippest group going. As punk was becoming a distant echo, they appeared with a sound and an attitude that gazed back longingly to the age of Seventies pomp. When compared to Yes, Genesis and ELP, they would take it as a compliment. The Eighties have seen some odd phenomena. But none quite as odd as Marillion. Along the way, as if by glorious fluke, they turned out some singles that everybody quietly liked – "Garden Party", "Punch and Judy" and "Incommunicado". By this time, Marillion did not need the support of the hip-conscious. They were massive. Perhaps the oddest thing about Marillion was that they became one of the biggest groups of the decade. They might have been an anomaly but they were monstrously effective.[82]

The band's unfashionable reputation and image has often been mentioned in the media, even in otherwise positive reviews. In Q in 1987, David Hepworth wrote: "Marillion may represent the inelegant, unglamorous, public bar end of the current Rock Renaissance but they are no less part of it for that. Clutching at Straws suggests that they may be finally coming in from the cold."[83] In the same magazine in 1995, Dave Henderson wrote: "It's not yet possible to be sacked for showing an affinity for Marillion, but has there ever been a band with a larger stigma attached?" He also argued that if the album Afraid of Sunlight "had been made by a new, no baggage-of-the-past combo, it would be greeted with open arms, hailed as virtual genius."[84] In Record Collector in 2002, Tim Jones argued they were "one of the most unfairly berated bands in Britain" and "one of its best live rock acts."[85] In 2004, Classic Rock's Jon Hotten wrote: "That genre thing has been a bugbear of Marillion's, but it no longer seems relevant. What are Radiohead if not a progressive band?" and said Marillion were "making strong, singular music with the courage of their convictions, and we should treasure them more than we do."[52] In the Q & Mojo Classic Special Edition Pink Floyd & The Story of Prog Rock, an article on Marillion written by Mick Wall described them as "probably the most misunderstood band in the world".[86]

In 2007, Stephen Dalton of The Times stated:

The band have just released their 14th album, Somewhere Else, which is really rather good. Containing tracks that shimmer like Coldplay, ache like Radiohead and thunder like Muse, it is better than 80 per cent of this month's releases. But you are unlikely to hear Marillion on British radio, read about them in the music press or see them play a major festival. This is largely because Marillion have – how can we put this kindly? – an image problem. Their music is still perceived as bloated, bombastic mullet-haired prog-rock, even by people who have never heard it. In fairness, they did once release an album called Script for a Jester's Tear. But, come on, we all had bad hair days in the 1980s.[78]

Despite publishing a very good review for their 1995 album Afraid of Sunlight and including it in their 50 Best Albums of 1995, Q refused to interview the band or write a feature on them. Steve Hogarth later said: "How can they say, this is an amazing record... no, we don't want to talk to you? It's hard to take when they say, here's a very average record... we'll put you on the front cover."[40]

In 2001, the television critic of The Guardian, Gareth McLean, used his review of the Michael Lewis BBC Two documentary, Next: The Future Just Happened, to concentrate on launching a scathing attack on the band, whose appearance only constituted one segment of the programme. He described them as "once dodgy and now completely rubbish" and he characterised their fans as "slightly simple folks". He also dismissed the band's efforts to continue their career without a label by dealing directly with their fans on the Internet, writing: "One suspects that their decision occurred round about the time that the record industry decided to shun Marillion."[87]

Rachel Cooke, a writer for The Observer and New Statesman, has repeatedly referred negatively to the band and insulted their fans in her articles.[88][89][90][91]

In an interview in 2000, Hogarth expressed regret about the band retaining their name after he joined:

If we had known when I joined Marillion what we know now, we'd have changed the name and been a new band. It was a mistake to keep the name, because what it represented in the mid-Eighties is a millstone we now carry. If we'd changed it, I think we would have been better off. We would have been judged for our music. It's such a grave injustice that the media constantly calls us a 'dinosaur prog band'. They only say that out of ignorance because they haven't listened to anything we've done for the last 15 bloody years. If you hear anything we've done in the last five or six years, that description is totally irrelevant... It's a massive frustration that no-one will play our stuff. If we send our single to Radio 1 they say: 'Sorry, we don't play music by bands who are over so-many years old... and here's the new U2 single.' I suppose it's something everyone has to cope with – every band are remembered for their big hit single, irrespective of how much they change over the years. But you can only transcend that by continuing to have hits. It's Catch 22. You know, at some stage, someone has to notice that we're doing interesting things. Someday someone will take a retrospective look at us and be surprised.[92]

The 2013 film Alan Partridge: Alpha Papa includes a joke reference to a former drummer of the band. The band were quoted: "We know Marillion are seen as 'uncool' but we were delighted to be a part of it."[93]

Crowdfunding pioneers

Marillion are widely considered to have been one of the first mainstream acts to have fully recognised and tapped the potential for commercial musicians to interact with their fans via the internet, starting in around 1996, and are nowadays often characterised as a rock & roll 'Web Cottage Industry'.[94][95] The history of the band's use of the Internet is described by Michael Lewis in the book Next: The Future Just Happened as an example of how the Internet is shifting power away from established elites, such as multinational record labels and record producers.

The band are renowned for having an extremely dedicated following (often self-termed 'Freaks'),[94] with some fans regularly travelling significant distances to attend single gigs, driven in large part by the close fan base involvement which the band cultivate via their website, podcasts, biennial conventions[96] and regular fanclub[97] publications. The release of their 2001 album Anoraknophobia, which was funded by their fans through advance orders instead of by the band signing to a record company, gained significant attention and was called "a unique funding campaign" by the BBC.[98] Writing for The Guardian, Alexis Petridis described Marillion as "the undisputed pioneers" of fan-funded music.[81]

Personnel

Members

|

|

Lineups

| 1979–1981 | 1981 | 1981–1982 | 1982–1983 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| 1983 | 1983 | 1983–1984 | 1984–1988 |

|

|

|

|

| 1989–present | |||

|

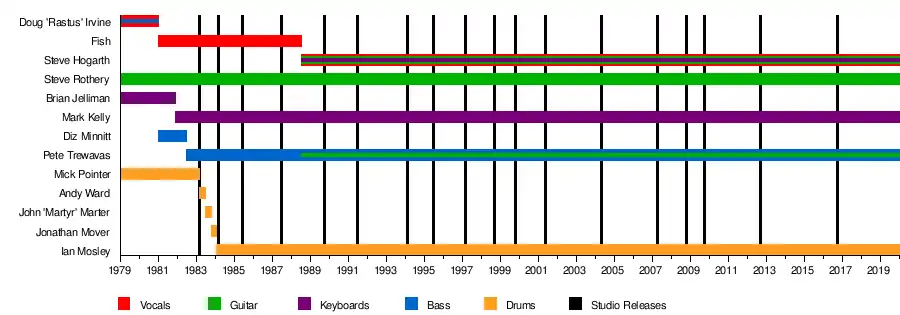

Timeline

Discography

- Studio Albums

- Script for a Jester's Tear (1983)

- Fugazi (1984)

- Misplaced Childhood (1985)

- Clutching at Straws (1987)

- Seasons End (1989)

- Holidays in Eden (1991)

- Brave (1994)

- Afraid of Sunlight (1995)

- This Strange Engine (1997)

- Radiation (1998)

- marillion.com (1999)

- Anoraknophobia (2001)

- Marbles (2004)

- Somewhere Else (2007)

- Happiness Is the Road (2008)

- Less Is More (2009)

- Sounds That Can't Be Made (2012)

- Fuck Everyone and Run (F E A R) (2016)

- With Friends from the Orchestra (2019)

References

- Banks, Joe. "Neo-Prog Three Decades On: Marillion, IQ, Pendragon Etc. Revisited". The Quietus. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Prasad, Anil. "Marillion - Forward motion". Innerviews. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

The band has often been compared to Genesis and Yes because of its exploration of swirling, symphonic rock that occasionally veers into accessible pop territory

- Michael Ray, ed. (2012). Disco, punk, new wave, heavy metal, and more: Music in the 1970s and 1980s. Rosen Education Service. p. 106. ISBN 978-1615309085.

...the appearance of the influential British art rock bands U.K. and Marillion in the late 1970s and early 1980s, respectively

- Blair, Iain (23 March 1986). "STEP ASIDE, PUNKS, MARILLION MAKING '70S-TYPE OF NAME FOR ITSELF". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Romano, Will (2010). Mountains Come Out of the Sky: The Illustrated History of Prog Rock. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0879309916. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

...Marillion emerged from the post-punk music scene in Britain... Marillion existed as a bridge between punk and classic progressive rock

- "Neo-Prog". Allmusic. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Allmusic review of Marbles

- Allmusic review of Marbles Live

- 50 Best Live Acts of All Time (April 2008). Classic Rock Magazine. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- "Passenger Edges Out Bruce Springsteen for No. 1 Album on U.K. Charts". Billboard. 30 September 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- "'Gutted' Fish lives happily ever after". The Scotsman. The Scotsman Publications. 19 September 2008. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Elliott, Paul (17 July 2016). ""I was an arsehole": Fish looks back on his career and reveals what's next". Louder. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- Mick Wall (1987). Market Square Heroes – The Authorised Story of Marillion. Sidgwick & Jackson Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-283-99426-5.

- Kreutzmann Andre, andre(at)morain de (1 June 2002). "Marillion Setlists - 1980". Morain.de. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- "Welcome to the Friars Aylesbury website". Aylesburyfriars.co.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- Carol Clarke, "Marillion In Words & Pictures" (1985)

- Marcelo Silveyra (2002). "Chapter 1 – Writing Down The Script". Progfreaks.com. Archived from the original on 4 June 2008.

- "A trip down memory lane «". Siba.co.uk. 26 February 2013. Archived from the original on 18 July 2013. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- https://www.setlist.fm/venue/the-red-lion-bicester-england-5bd643d0.html

- "Interview: Heather from Steam Shed - SouthWaves Audio SouthWaves Audio". Southwavesaudio.co.uk. 26 June 2018. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- "Interview - Diz Minnitt of Marillion". The Marquee Club. Archived from the original on 24 December 2006. Retrieved 19 April 2014.

- "Record News", Sounds, 14 December 1985, p. 6

- "Zealey And Moore". Zealeyandmoore.co.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- David Roberts, ed. (2006). British Hit Singles and Albums. Guinness World Records Limited. p. 349. ISBN 978-1904994107.

- Popoff, Martin (2016). Time And a Word: The Yes Story. Soundcheck Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-0993212024.

- Ling, Dave (October 2001). "Fish interview". Classic Rock. Retrieved 3 August 2015.

- Larkin, Colin (2007). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th ed.). Bish Bash Books. ISBN 978-1846098567. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- Jensen, Dale. "Marillion". AllMusic. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- David Roberts, ed. (2006). British Hit Singles and Albums. Guinness World Records Limited. p. 450. ISBN 978-1904994107.

- David Roberts, ed. (2006). British Hit Singles and Albums. Guinness World Records Limited. p. 533. ISBN 978-1904994107.

- "Kerrang!'s Albums Of 1985 by Kerrang! (1985)". Best Ever Albums. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- "Phil Cunliffe meets Marillion hero". BBC News. 3 September 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- O'Neill, Eamon (6 September 2014). "Steve Rothery - Marillion - Uber Rock Interview Exclusive". Uber Rock. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- Rob Hendriks. "Interview June 2002". The Web magazine. Archived from the original on 28 November 2010.

- "1987 Q Magazine Recordings of the Year". Rocklist.net. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- Edinburgh Evening News, 29 May 2003.

- "Back singing for his supper after taking stock". The Scotsman. UK. 29 May 2003.

- "Tour history 1988". Archived from the original on 1 January 2010.

- "Singer Fish and Marillion reunite". BBC News. 28 August 2007.

- Dave Ling (May 2001) Classic Rock Magazine

- "MUSIC – Discography – Holidays in Eden". Marillion.com. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Q, February 1996.

- "Out of this World, Trivia". Marillion.com. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "Band Member Journal : A Day in the Lakes". Marillion.com. 8 March 2001. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "Afraid of Sunlight Sleeve Notes". Marillion.com.

- "NEWS – Press Room – Anoraknophobia". Marillion.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "MUSIC – Discography – Radiation". Marillion.com. 15 October 1998. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "MUSIC – Discography – Anoraknophobia". Marillion.com. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "MUSIC – Discography – Marbles". Marillion.com. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Betty Clarke The Guardian, 30 April 2004.

- Tim Jones Record Collector, May 2004, Issue 297.

- Jon Hotten Classic Rock, May 2004, Issue 66.

- Roger Newell Guitarist, June 2004

- Simon Gausden Powerplay, June 2004

- Guitar, June 2004

- The Star, June 2004

- "Marillion bringing Happiness to JB's". Shropshire Star. 12 November 2008. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013.

- "Marillion – Whatever is Wrong with You? – Video Contest". 26 July 2008. Archived from the original on 26 July 2008.

- Marillion Press Release (11 September 2008) "Marillion Use P2P for Album Release" Anti Music

- "Hawkwind star honoured at awards". BBC News. 4 September 2013. Retrieved 4 September 2013.

- "Marillion Album 18 Pre-Order Campaign". Marillion.com. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Marillion: New Album on PledgeMusic". PledgeMusic. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Stickler, Jon (30 November 2016). "Marillion Confirm First Ever Show At London's Royal Albert Hall". stereoboard.com. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- "Marillion, Anathema, Steve Hackett among Progressive Music Award winners". teamrock.com. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 25 September 2017.

- Laura Snapes (27 March 2018). "'Feed the homeless first': new David Bowie statue vandalised". The Guardian.

- "David Bowie sculpture vandalised 48 hours after unveiling". Irish News. 27 March 2018.

- Lester, Paul (31 August 2016). "The rise and rise of Marillion – the band that refuses to die". Louder. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- "Marillion lineup". Separatedout.com. Archived from the original on 13 March 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Dean, Mark (10 December 2016). "Interview: Steve Rothery of MARILLION". AntiHero Magazine. Retrieved 26 October 2019.

- Reesman, Bryan (17 August 2010). "Iron Maiden's Janick Gers Talks Festivals, Fish and The Final Frontier". bryanreesman.com. Retrieved 23 August 2019.

- Prasad, Anil. "Fish: Mirroring influences". Innerviews. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Mann, Rachel (20 May 2013). "This Must Be The Plaice: Fish's Favourite Albums". The Quietus. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Steve Rothery Interview". All Access Magazine. 27 August 2009. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 24 March 2014.

- Kahn, Scott. "Marillion's Mark Kelly: Keyboards in Eden". Musicplayers.com. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- Ward, Steven. "Interview with Pete Trewavas of Marillion". PopMatters. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Mick Pointer interview". New Horizons. Archived from the original on 20 September 2015. Retrieved 20 August 2015.

- "Anoraknophobia Pre-Order Press Release". Marillion.com. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Stephen Dalton (21 April 2007). "How to thrive on a Fish-free diet". rock's back pages library. UK.

- Kirkley, Paul (12 September 2012). "From prog to a prince: how Marillion took on the music industry - and won". Cambridge News. Cambridge.

- Chakerian, Peter (26 October 2016). "Marillion survives, thanks to Clevelander and the Internet". cleveland.com. Retrieved 28 October 2016.

- Petridis, Alexis (18 April 2008). "This song was brought to you by ..." The Guardian. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Jonh Wilde. "Fish - A Chip Off the Shoulder". p 42-43. Melody Maker. 28 October 1989

- David Hepworth (July 1987) Review of Clutching at Straws, Q Magazine (archived at Official Fish Site)

- Dave Henderson Q, August 1995.

- Tim Jones Record Collector, May 2002.

- Mick Wall Q Classic: Pink Floyd & The Story of Prog Rock, 2005.

- Gareth McLean (13 August 2001). "In the realm of pretences". The Guardian. UK.

- "Reader, I loved it". The Observer. UK. 26 November 2006.

- "I get the picture: comics can be cool". The Observer. UK. 15 July 2007.

- "I just can't get you out of my head". New Statesman. UK. 26 June 2008.

- "The Anti-Social Network (BBC3)". New Statesman. UK. 26 March 2012.

- Chris Leadbeater. "The band that broke the mould". London Evening Standard. 28 November 2000

- Adam Sherwin (23 July 2013). "A-ha! Alan Partridge movie Alpha Papa gives airtime to forgotten pop classics". The Independent. UK.

- Big George Webley. "Sound on Sound". Sound on Sound. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "Web Cottage Industry" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 August 2011. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "weekend Marillion convention website". Marillionweekend.com. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- "The Web – Marillion fansite". Theweb-uk.com. Retrieved 19 August 2011.

- Masters, Tim (11 May 2001). "Marillion fans to the rescue". BBC News. Retrieved 27 March 2014.