Meera (1945 film)

Meera is a 1945 Indian Tamil-language musical drama film directed by Ellis R. Dungan, produced by T. Sadasivam and written by Kalki Krishnamurthy. The film stars M. S. Subbulakshmi as the eponymous 16th century mystic and poet, a zealous devotee of Krishna, considering him to be her husband. Despite marrying Rana (Chittor Nagaiah), she follows her own way of living which is not acceptable to her husband and his family.

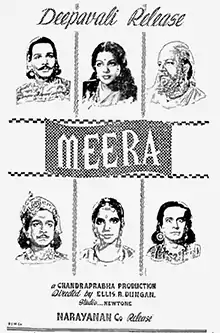

| Meera | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ellis R. Dungan |

| Produced by | T. Sadasivam |

| Written by | Kalki Krishnamurthy |

| Starring | M. S. Subbulakshmi |

| Music by | S. V. Venkatraman |

| Cinematography | Jitan Banerji |

| Edited by | R. Rajagopal |

Production company | Chandraprabha Cinetone |

| Distributed by | Narayanan & Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 136 minutes[1] |

| Country | India |

| Language | Tamil |

Sadasivam wanted to produce a film that would take his singer wife Subbulakshmi's music even to the common man, so he started looking for a good story; Subbulakshmi chose the story of Meera. The film began production at Newtone Studio in Madras, but was predominantly filmed on location in North India in places like Jaipur, Vrindavan, Udaipur, Chittor and Dwarka to maintain credibility and historical accuracy.

Meera was released on 3 November 1945, Diwali day. The film became a major critical and commercial success; this led to the creation of a Hindi-dubbed version, which had a few scenes reshot, that was released two years later on 21 November and also achieved success. Despite the Hindi version making Subbulakshmi a national celebrity, it would be her last film as an actress, after which she decided to focus solely on her musical career.

Plot

During the reign of the Mughal emperor Akbar, young Meera, influenced by the story of Andal and Krishna, is deeply in love with Krishna, so much so that she considers him to be her husband after she garlands him on an auspicious day as advised by her mother. As Meera grows into a young woman, her devotion to Krishna grows.

Against her wishes, Meera is married to Rana, the king of Mewar. But even after marriage, her love for Krishna remains unchanged. She follows her own ideals and way of living which are not acceptable to Rana and his family, especially his brother Vikram and sister Udha. Meera requests Rana to construct a temple for Krishna in Chittor, the capital of Mewar. Out of love for her, Rana assents. An overjoyed Meera remains in the temple most of the time, singing in praise of Krishna along with other devotees and avoids staying at the palace.

On Vijayadashami, Rana expects Meera to be with him at the royal assembly, when other kings come to offer their respects. But en route to the assembly, Meera hears Krishna's flute playing, returns to the temple and remains there. Rana gets angry upon realising that Meera has returned to the temple again, ignoring her duties as a wife. To kill Meera, Vikram gives a poisoned drink through Udha, but Meera is saved by Krishna and the poison does not kill her; instead, Krishna's idol at the Vithoba Temple turns blue, and sanctum double-doors at Dwarakadheesh Temple close spontaneously, and remain closed.

At Delhi, Akbar learns about Meera's singing and devotion to Krishna. He sends her a pearl necklace as a gift, which Meera puts on Krishna's idol. Rana becomes angry when he comes to know of these developments and her disinterest to fulfil her duties as a wife and queen; he orders the demolition of the temple using cannons so that she will come out. Vikram goes to the temple and orders Meera and the other devotees to come out before the demolition begins. However, Meera refuses, stays back in the temple and continues her bhajans.

Meanwhile, Rana learns from Udha about Vikram's failed attempt to kill Meera. Shocked when he realises Meera's real identity (she is one with Krishna), he rushes to meet her in the temple which is about to be demolished. When a cannon is fired, Rana stops it and gets injured. When Meera hears Krishna calling her, she admits to Rana that she has failed in her duties as a wife. She explains that her heart is with Krishna and seeks Rana's permission to leave palace life and fulfill her desire to visit Krishna's temple at Dwarka; Rana realises her devotion and assents. Once Meera leaves, Mewar suffers from a drought and the subjects plead with Rana to bring Meera back, so Rana goes in search of her.

Meera first goes to Brindavanam and meets the sage who originally predicted her devotion. Together, they leave for Dwarka, the birthplace of Krishna; on reaching the temple, she starts singing in praise of Krishna. Rana, who has followed her, also reaches the temple. The doors of the temple, which were closed till then, open. Krishna appears and invites Meera inside. Meera runs towards Krishna and falls dead while her soul merges with him. Rana comes rushing in only to find Meera's corpse. Meera's devotion to Krishna is finally rewarded and she is united with him.

Cast

- M. S. Subbulakshmi as Meera

- Chittor Nagaiah as Rana

- Radha as Young Meera

- Serukalathur Sama as Rupa Goswami[2]

- K. Sarangapani as Udham[2]

- T. S. Balaiah as Vikram[2]

- K. R. Chellam as Udha[2]

- T. S. Mani and M. G. Ramachandran as Jayamal

- K. Duraisami as Messenger Rao[2]

- T. S. Durairaj as Narendran

- R. Santhanam as Surendran[2]

Baby Kamala portrays Krishna, while Jayagowri and Leela portray roles not named in the opening credits.[2]

Production

Development

T. Sadasivam wanted to produce a film that would take his singer wife M. S. Subbulakshmi's music even to the common man, so he started looking for a good story. He had several discussions with friends like Kalki Krishnamurthy, and was of the opinion that if Subbulakshmi was to act in a film, it could not be a mass entertainer, but would need to carry a universal and uplifting message for the masses. After much deliberation, Subbulakshmi herself chose the story of the 16th century mystic and poet Meera.[3] Sadasivam decided to produce the film entirely on his own under the banner Chandraprabha Cinetone, and for the first time was not answerable to any financier, co-producer or co-partner. He chose Ellis R. Dungan to direct, while Krishnamurthy was hired as screenwriter.[4] Jitan Banerji was the cinematographer, and R. Rajagopal the editor.[5] This would be the second film based on Meera, after the 1938 film Bhakta Meera.[6]

Casting

While Subbulakshmi was cast as Meera, her stepdaughter Radha was recruited to play the younger version.[7] To prepare for the part, Subbulakshmi decided to go to all the places where Meera had wandered in search of the elusive Krishna, and would worship at all the temples where Meera worshipped.[8] Honnappa Bhagavathar was the first choice to play Meera's husband Rana which he accepted, but was ultimately not retained; in a 1990 interview he recalled, "I had met Sadasivam, and after discussions he told me that he would make arrangements for an advance payment and agreement, but I never heard from him again". An undisclosed person suggested P. U. Chinnappa, but Dungan refused as he felt Chinnappa was "uncouth" and lacked the "regal presence" needed for the role. Chittor Nagaiah, who Dungan recommended, was eventually cast; according to Dungan, he "proved the right choice for a Rajput king".[7]

The husband-and-wife comedy duo N. S. Krishnan and T. A. Mathuram were supposed to have acted in Meera. However, Krishnan was arrested in December 1944 as a suspect in the Lakshmikanthan murder case, and he was replaced by T. S. Durairaj who portrayed Narendran; Madhuram too did not remain on the project.[9][2] T. S. Mani and M. G. Ramachandran shared the role of a minister named Jayamal.[2][10] This was the only film where two future Bharat Ratna laureates (Ramachandran and Subbulakshmi) acted.[10] Baby Kamala, a girl, was chosen to act as the male Krishna.[11][12]

Filming

Production began in 1944 at Newtone Studio in Madras, before moving to North India, particularly Rajasthan, for location shooting.[3][13] According to filmmaker and historian Karan Bali, Dungan and Banerji "did a series of elaborate lighting tests on a specially created bust of [Subbulakshmi]. They shot the bust using different camera heights and angles with varied lighting schemes. They then studied the developed rushes to decide what worked best for Subbulakshmi's face structure."[13] Shooting locations included Rajasthan's capital Jaipur, in addition to Vrindavan, Udaipur, Chittor and Dwarka.[3] The decision to shoot in these locations was Dungan's, who cited the need to be "credible and historically accurate".[8]

At Udaipur, Sadasivam required some royal elephants and horses for the shooting schedule. After he made a request to the-then Maharana of Udaipur, the latter agreed to help the crew with whatever they needed beyond elephants and horses.[14] Dungan recalled in his autobiography, "Due to the kindness and assistance of the Maharana's prime minister, we were given carte blanche to film practically anything and anywhere in and around the palaces and gardens [...] We were also granted the use of such facilities as the royal barge, elephants, a royal procession, the palace dancing girls, hundreds of film "extras" and all of the water fountains in and around the palaces. These were ready-made sets and would have cost us a fortune to reproduce in a studio setting, if they could be reproduced at all."[13]

While filming at Dwarka, Dungan could not enter the Krishna temple where permission to shoot the film had been obtained, as he was not a Hindu. Hence, he disguised himself as a Kashmiri Pandit and was let in.[7][10] Another scene required Meera to cross the Yamuna in a boat; the boat would capsize and she would be saved by Krishna who would appear in the guise of a boatman. While filming the scene, Subbulakshmi accidentally hurt her head and fell unconscious; the crew barely rescued her from drowning.[8][15] The final length of the film was 10,990 feet (3,350 m).[1]

Themes

Subbulakshmi's biographer Lakshmi Viswanathan noted many parallels between her and the film version of Meera, saying, "Meera was married at a tender age to a much older man, the Maharana. Her great obsession with Krishna led her to a spiritual path, away from the pomp of the royal palace and all that it stood for. She sang the most evocative bhajans on Krishna and wandered about like a minstrel followed by a host of devotees until she attained moksha – that magical moment when the enlightened soul unites with the eternal spirit."[16]

Soundtrack

The soundtrack was composed by S. V. Venkatraman,[17] and released under the HMV label.[18] The song "Kaatrinile Varum Geetham", written by Krishnamurthy, is set in the Carnatic raga known as Sindhu Bhairavi,[19][20] and based on "Toot Gayi Man Bina", a Hindi-language non-film song composed by Kamal Dasgupta and sung by Sheila Sarkar.[21] While historian Randor Guy claimed that Krishnamurthy suggested the tune to Venkatraman,[7] another historian V. Sriram says Krishnamurthy's daughter Anandi pestered for him to write a Tamil version of the song.[22] "Brindhavanatthil" and "Engum Niraindhaaye" are also set in Sindhu Bhairavi,[23] while "Giridhara Gopala" is set in Mohanam.[24]

| No. | Title | Singer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Aranga Un Mahimayai" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:21 |

| 2. | "Brindhavanatthil" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:17 |

| 3. | "Charaa Charam" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 4:21 |

| 4. | "Devika Tamizh Naattinele" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:30 |

| 5. | "Enathullamae" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:04 |

| 6. | "Engum Niraindhaaye" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 2:12 |

| 7. | "Giridhara Gopala" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 2:32 |

| 8. | "Hey Harey" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:34 |

| 9. | "Ithanai Naalaana Pinnum" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 2:42 |

| 10. | "Kaatrinile Varum Geetham" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:03 |

| 11. | "Kandathundo Kannan Pol" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:20 |

| 12. | "Kannan Leelaigal" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:17 |

| 13. | "Maala Pozhuthinile" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 5:44 |

| 14. | "Maanilathai Vaazha Vaika" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:24 |

| 15. | "Maraindha Koondilirudhu" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 2:09 |

| 16. | "Maravene" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 2:25 |

| 17. | "Nandabala" | M. S. Subbulakshmi, Baby Radha | 3:47 |

| 18. | "Thavamum Palithathamma" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:20 |

| 19. | "Udal Uruga" (verse) | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 3:20 |

| 20. | "Vandaadum Cholai" | M. S. Subbulakshmi | 6:15 |

Release and reception

Meera was released on 3 November 1945, Diwali day, and distributed by Narayanan & Company.[25] The distributors put out front-page advertisements to announce "the musical movie of your dreams" and specifically to inform all fans that the "song hits" of the film were available on HMV records.[18] The film received rave reviews; The Free Press Journal said, "Meera transports us into a different world of bhakti, piety and melody. It shatters the misguided belief that film music is inferior. Subbulakshmi follows no stereotyped techniques in acting. She is just Meera."[26] Kay Yess Enn of The Indian Express wrote on 10 November, "[Subbulakshmi] reveals a flair for histrionic heights in some scenes but in general, though showing great improvement on her previous efforts, there is scope for better work in emotional scenes."[27] However, the magazine Picturpost (15 November) was more critical, saying the Meera bhajans were not "too pleasing to hear", the film lacked conviction, realism and was not emotional enough. The reviewer felt Subbulakshmi, a Carnatic singer, was miscast as Meera, a Hindustani singer, and Dungan's direction was "bungling".[28] The film was a major box office success; according to Smt. C. Bharathi, author of the 2008 book M. S. Subbulakshmi, this was largely due to the songs than the acting.[29]

The success of Meera prompted Sadasivam to dub it in Hindi while having some scenes reshot.[13] The Hindi-dubbed version was released on 21 November 1947,[30] and achieved equal success, making Subbulakshmi a national celebrity.[13] The film had an on-screen introduction by the politician and poet, Sarojini Naidu, who described Subbulakshmi as "The Nightingale of India".[31] The film was seen by Jawaharlal Nehru and the Mountbatten family who then became Subbulakshmi's ardent fans, further propelling her fame.[7][11] A reviewer from The Bombay Chronicle said, "More than the story of the Queen of Mewar who preferred a heavenly to an earthly diadem it is the voice of the star singing her bhajans and padas that is the picture's chief attraction [...] Narendra Sharma's lyrics embellish this photoplay, the story of which is from the pen of Amritlal Nagar. Subbulakshmi's admirers will find this film highly entertaining."[32][33] Despite the success of Meera, it was Subbulakshmi's last film as an actress, after which she focused solely on her musical career.[13][34] The film was screened at various film festivals such as Prague Film Festival, Venice Film Festival and Toronto International Film Festival.[35]

Legacy

The scene where young Meera transforms into her older self, and the transition is shown with the song, "Nandha Balaa En Manalaa..", became a milestone in Indian cinema for its filmmkaing technique.[36] On the April 2013 centenary of Indian cinema, CNN-IBN (later known as CNN-News18) included Meera in its list of the "100 greatest Indian films of all time".[37] Meera is considered as a musical cult of Tamil cinema.[38]

References

- Rajadhyaksha & Willemen 1998, p. 304.

- Meera (motion picture) (in Tamil). Chandraprabha Cinetone. 1945. Opening credits, from 0:15 to 0:32.

- Viswanathan 2003, p. 59.

- George 2016, pp. 142–143.

- Meera (motion picture) (in Tamil). Chandraprabha Cinetone. 1945. Opening credits, from 0:38 to 0:47.

- Dhananjayan, G. (15 August 2016). "Artistic amends – Flops a reservoir of hot story ideas". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 3 December 2019. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Guy, Randor (17 December 2004). "Full of technical innovations". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 25 January 2013. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Ramnarayan, Gowri (17 September 2004). "Brindavan to Dwaraka – Meera's pilgrimage". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 November 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Guy, Randor (16 July 2015). "Overshadowed by peer". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 26 November 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- Ramakrishnan, Venkatesh (21 January 2018). "Those were the days: An unlikely pioneer in Tamil cinema". DT Next. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Guy, Randor (28 March 2008). "Meera 1945". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 30 August 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2019.

- Guy, Randor (7 January 2002). "She danced her way to stardom". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Bali, Karan (16 September 2016). "The making of MS Subbulakshmi's 'Meera', her final and finest film". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 21 October 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Viswanathan 2003, p. 62.

- Viswanathan 2003, pp. 63–65.

- Viswanathan 2003, pp. 62–63.

- "Meera". JioSaavn. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2019.

- George 2016, p. 143.

- Saravanan, T. (20 September 2013). "Ragas hit a high". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 26 December 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Jeyaraj, D. B. S. (19 August 2018). "♥'Kaatriniley Varum Geetham'-Melodiously Sung by M.S. Subbulakshmi in/as "Meera"♫". DBSJeyaraj.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- Vamanan (10 December 2018). "இந்தி திரைப்பாடல் தமிழுக்கு தந்த இனிமை!". Dinamalar. Nellai. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Sriram, V. (30 May 2018). "The Tune Behind Katrinile Varum Geetham". Madras Heritage and Carnatic Music. Archived from the original on 6 June 2019. Retrieved 6 June 2019.

- Sundararaman 2007, pp. 126, 129.

- Sundararaman 2007, p. 131.

- "Meera". The Indian Express. 3 November 1945. p. 5.

- Gangadhar 2002, p. 47.

- Kay Yess Enn (10 November 1945). "Meera | M.S.S. At Her Musical Best". The Indian Express. p. 8.

- Dwyer 2006, p. 88

- Bharathi, Smt. C. (9 May 2008). M. S. Subbulakshmi. Sapna Book House. ISBN 9788128007347.

The film was a tremendous success, more because of the songs than of the acting.

- Raman, Mohan V. (16 September 2016). "In Only Five Films, M.S. Subbulakshmi Made Her Way to the Stars". The Wire. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- Seshan, A. (11 September 2015). "When M S Subbulakshmi brought Meera to life". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 28 November 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- Dwyer 2006, p. 89.

- Dwyer 2006, p. 175.

- Muthiah, S. (21 January 2002). "He made MS a film star". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2 September 2014.

- Devika Bai, D. (11 May 2014). "Tamil classics from American director". New Straits Times. Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- Guy, Randor (1 February 2001). "He transcended barriers with aplomb". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 3 January 2013.

- "100 Years of Indian Cinema: The 100 greatest Indian films of all time". CNN-IBN. 17 April 2013. Archived from the original on 25 April 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- Dhananjayan, G. (2014). Pride of Tamil Cinema: 1931 to 2013: Tamil Films that have earned National and International Recognition. Blue Ocean Publishers. p. 63.

Bibliography

- Dwyer, Rachel (2006). Filming the Gods: Religion and Indian Cinema. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-38070-1. OCLC 878593281.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gangadhar, V. (2002). M.S. Subbulakshmi: The Voice Divine. Rupa Publications. OCLC 607561598.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- George, T. J. S. (2016). M.S. Subbulakshmi: The Definitive Biography. Aleph Book Company. ISBN 9789384067601.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rajadhyaksha, Ashish; Willemen, Paul, eds. (1998) [1994]. Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema (PDF). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-563579-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sundararaman (2007) [2005]. Raga Chintamani: A Guide to Carnatic Ragas Through Tamil Film Music (2nd ed.). Chennai: Pichhamal Chintamani. OCLC 295034757.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Viswanathan, Lakshmi (2003). Kunjamma: Ode to a Nightingale. Roli Books. OCLC 55147492.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)