Megalonyx

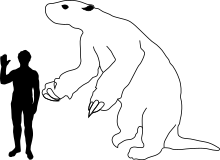

Megalonyx (Greek, "large claw") is an extinct genus of ground sloths of the family Megalonychidae, native to North America during Pleistocene epoch. It became extinct during the Quaternary extinction event at the end of the Rancholabrean of the Pleistocene, living from ~2.4 Mya—11,000 years ago. The type species, M. jeffersonii, measured about 3 meters (9.8 ft) and weighed up to 1,000 kilograms (2,200 lb).[2] Megalonyx is descended from Pliometanastes, a genus of ground sloth that had arrived in North America during the Late Miocene, prior to the Great American Biotic Interchange. Megalonyx had the widest distribution of any North American ground sloth, having a range encompassing most of the contiguous United States, extending as far North as Alaska during warm periods.

| Megalonyx | |

|---|---|

| |

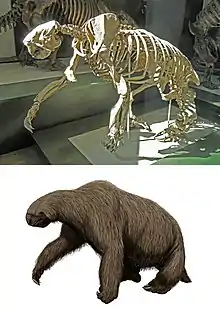

| M. wheatleyi skeleton and restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Pilosa |

| Family: | †Megalonychidae |

| Genus: | †Megalonyx Harlan 1825 |

| Species | |

Taxonomy

In 1796, Colonel John Stuart sent Thomas Jefferson, then Vice President of the United States, some fossil bones: a femur fragment, ulna, radius, and foot bones including three large claws. The discoveries were made in a cave in Greenbrier County, Virginia (present-day West Virginia). Jefferson examined the bones and presented his observations in the paper "A Memoir on the Discovery of Certain Bones of a Quadruped of the Clawed Kind in the Western Parts of Virginia" to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia on March 10, 1797. In the paper, he named the then unknown animal Megalonyx ("giant claw") and compared each recovered bone to the corresponding bone in a lion.[3] Jefferson did not attempt a definitive taxonomic classification and kept an open mind, writing “Let us only say then, what we may safely say, that he was more than three times as large as the lion”. In his postscript, Jefferson mentions the remains of a Megatherium discovered in Paraguay and notes its anatomical similarities to Megalonyx.

Contrary to the scientific consensus emerging at the time that extinction had played an important role in natural history, Jefferson believed in a "completeness of nature" whose inherent balance did not allow species to go extinct naturally. He asked Lewis and Clark, as they planned their famous expedition in 1804–1806, to keep an eye out for living specimens of Megalonyx, as this would support his case. His idea made no headway and was later shown to be incorrect.[4]

His presentation to the American Philosophical Society in 1797 is often credited as the beginning of vertebrate paleontology in North America. In 1799, Dr Caspar Wistar correctly identified the remains as those of a giant ground sloth. In 1822, Wistar proposed naming the species Megalonyx jeffersonii in honor of the former statesman.[5][6] Desmarest then published it as such. Megalonyx was first formally named by Richard Harlan in 1825.[7]

Recent research confirms that the sloth bones were discovered in Haynes Cave in Monroe County, West Virginia. For many decades in the twentieth century, the reported origin of Jefferson's "Certain Bones" was Organ Cave in what is now Greenbrier County, West Virginia. This story was popularized in the 1920s by a local man, Andrew Price of Marlinton.[8] The story came under scrutiny when in 1993 two fragments of a Megalonyx scapula were found in Haynes Cave in neighboring Monroe County. Smithsonian paleontologist Frederick Grady presented evidence in 1995 confirming[9] Haynes Cave as the original source of Jefferson's fossil. Jefferson reported that the bones had been found by saltpeter workers. He gave the cave owner's name as Frederic Crower. Correspondence between Jefferson and Colonel Stuart, who sent him the bones, indicates that the cave was located about five miles from Stuart's home and that it contained saltpeter vats. An investigation of property ownership records revealed "Frederic Crower" to be an apparent misspelling of the name Frederic Gromer. Organ Cave was never owned by Gromer, but Haynes Cave was. Two letters written by Tristram Patton, the subsequent owner of Haynes Cave, indicate that this cave was located in Monroe County near Second Creek. Monroe County had originally been part of Greenbrier County; it became a separate county shortly after the discovery of the bones. In his own letters Patton described the cave and indicated that more fossil bones remained inside.[10]

M. jeffersonii is still the most commonly identified species of Megalonyx. It was designated the state fossil of West Virginia in 2008.

M. leptostomus, named by Cope (1893), lived from the Blancan to the Irvingtonian. This species lived from Florida to Texas, north to Kansas and Nebraska, and west to New Mexico, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington. It is about half the size of M. jeffersoni. It evolved into M. wheatleyi, the direct ancestor of M. jeffersonii. Species gradually got larger, with different species mostly based on size and geologic age.

Evolution

The first wave of Megalonychids came to North America by island-hopping across the Central American Seaway from South America, where ground sloths arose, prior to formation of the Panamanian land bridge. Based on molecular results, its closest living relatives are the three-toed sloths (Bradypus); earlier morphological investigations came to a different conclusion.[11][12]

After the formation of the Panamanian land bridge, the Great Blancan Faunal Interchange then brought the genus Megalonyx to the North American continent.

M. jeffersoni lived from the Illinoian Stage during the Middle Pleistocene (150,000 years BP) through to the Rancholabrean of the Late Pleistocene (11,000 BP[13]). It belongs to the genus Megalonyx, a name proposed by Thomas Jefferson, future president of the United States, in 1797. (Jefferson's surname was appended to the animal as the specific epithet in 1822 by the French zoologist Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest.) M. jeffersoni was probably descended from M. wheatleyi, which was in turn was probably derived from M. leptostomus.

Description

Megalonyx was a large, heavily built animal about 3 m (9.8 ft) long. Its maximum weight is estimated at 1,000 kg (2,200 lb).[2] This is medium-sized among the giant ground sloths. Like other ground sloths, it had a blunt snout, massive jaw, and large peg-like teeth. The hind limbs were plantigrade (flat-footed) and this, along with its stout tail, allowed it to rear up into a semi-erect position to feed on tree leaves. The forelimbs had three highly developed claws that were probably used to strip leaves and tear off branches.

Paleobiology

Ongoing excavations at Tarkio Valley in southwest Iowa may reveal something of the familial life of Megalonyx. An adult was found in direct association with two juveniles of different ages, suggesting that adults cared for young of different generations.[14][15]

Habitat

Megalonyx ranged over much of North and Central America.[16] Their remains have been found as far north as Alaska[17] and the Yukon during interglacial intervals.[18]

M. jeffersonii, also known as Jefferson's ground sloth, was apparently the most wide-ranging giant ground sloth. Fossils are known from many Pleistocene sites in the United States, including most of the states east of the Rocky Mountains as well as along the west coast. It was the only ground sloth to range as far north as the present-day Yukon.[18] Jefferson's ground sloth dwelled primarily in woodlands and forest, although they likely occupied a variety of habitats within these broad systems. Two recent studies were able to link directly dated specimens from the terminal Pleistocene with regional paleoenvironmental records, demonstrating that these particular animals were associated with spruce dominated, mixed conifer-hardwood habitat.

In late 2010, the first specimen ever found in Colorado was discovered at the Ziegler Reservoir site near Snowmass Village (in the Rocky Mountains at an elevation of 8,874 feet (2,705 m)).[19] The Firelands ground sloth fossil dated between 11,727 and 11,424 BCE represents the earliest-known hunting activity by Ohioan Paleo-Indians.[20]

References

Citations

- Megalonyx obtusidens at Fossilworks.org

- "Sandiegozoo". Archived from the original on 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- Jefferson, Thomas, "A Memoir on the Discovery of Certain Bones of a Quadruped of the Clawed Kind in the Western Parts of Virginia", Read before the American Philosophical Society, March 10, 1797.

- Rowland, Steve, "The Fossil Record", Published lecture notes for "The Fossil Record" course at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, August 2010

- Jefferson, Thomas (1799). "A Memoir on the Discovery of Certain Bones of a Quadruped of the Clawed Kind in the Western Parts of Virginia". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 4: 246–260. doi:10.2307/1005103. JSTOR 1005103.

- Wistar, Caspar (1799), "A Description of the Bones Deposited, by the President, in the Museum of the Society, and Represented in the Annexed Plates", Transactions, pp. 526-531, plates.

- McKenna, M.C.; Bell, S.K. (1997). Classification of Mammals: Above the Species Level. Columbia University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0-231-11013-8.

- Humphreys, Blanche (1928), History of Organ Cave Community (Greenbrier County, West Virginia); Agricultural Extension Division.

- Grady, Fred (1995), "The Search for the Cave from which Thomas Jefferson Described the Bones of the Megalonyx" [Abstract], In: "Selected Abstracts from the 1995 National Speleological Society National Convention in Blacksburg, Virginia"; In: Journal of Cave and Karst Studies, April 1997, pg 57.

- Grady (1995), Op. cit.

- Presslee, S.; Slater, G. J.; Pujos, F.; Forasiepi, A. M.; Fischer, R.; Molloy, K.; Mackie, M.; Olsen, J. V.; Kramarz, A.; Taglioretti, M.; Scaglia, F.; Lezcano, M.; Lanata, J. L.; Southon, J.; Feranec, R.; Bloch, J.; Hajduk, A.; Martin, F. M.; Gismondi, R. S.; Reguero, M.; de Muizon, C.; Greenwood, A.; Chait, B. T.; Penkman, K.; Collins, M.; MacPhee, R.D.E. (2019). "Palaeoproteomics resolves sloth relationships" (PDF). Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (7): 1121–1130. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0909-z. PMID 31171860. S2CID 174813630.

- Delsuc, F.; Kuch, M.; Gibb, G. C.; Karpinski, E.; Hackenberger, D.; Szpak, P.; Martínez, J. G.; Mead, J. I.; McDonald, H. G.; MacPhee, R.D.E.; Billet, G.; Hautier, L.; Poinar, H. N. (2019). "Ancient Mitogenomes Reveal the Evolutionary History and Biogeography of Sloths". Current Biology. 29 (12): 2031–2042.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.05.043. PMID 31178321.

- Fiedal, Stuart (2009). "Sudden Deaths: The Chronology of Terminal Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinction". In Haynes, Gary (ed.). American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene. Springer. pp. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8793-6_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-8792-9.

- Semken and Brenzel, "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2009-01-01. Retrieved 2009-09-25.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Semken; Brenzel (2007). "One Sloth Becomes Three". Newsletter of the Iowa Archeological Society. 57: 1.

- "Megalonyx". Paleobiology Database. Retrieved 2011-07-16.

- Stock, C. (1942-05-29). "A ground sloth in Alaska". Science. AAAS. 95 (2474): 552–553. Bibcode:1942Sci....95..552S. doi:10.1126/science.95.2474.552. PMID 17790868.

- McDonald, H. G.; Harington, C. R.; De Iuliis, G. (September 2000). "The Ground Sloth Megalonyx from Pleistocene Deposits of the Old Crow Basin, Yukon, Canada" (PDF). Arctic. Calgary, Alberta: Arctic Institute of North America. 53 (3): 213–220. doi:10.14430/arctic852. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- "Snowmass tally: 10 mastodons, 4 mammoths, one "once-in-a-lifetime" find". The Denver Post. November 18, 2010.

- "Research reveals first evidence of hunting by prehistoric Ohioans". Cleveland Museum of Natural History. February 2012. Archived from the original on 2012-05-14. Retrieved 2012-04-12.

Other sources

- Cope, ED. (1871) Preliminary report on the vertebrata discovered in the Port Kennedy Bone Cave. American Philosophical Society, 12:73-102.

- Cope, ED. (1893) A preliminary report on the vertebrate paleontology of the Llano Estacado. 4th Annual Report on the Geological Survey of Texas: 136pp.

- Hirschfeld, SE. and SD. Webb (1968) Plio-Pleistocene megalonychid sloths of North America. Bulletin of the Florida State Museum Biological Sciences, 12(5):213-296.