Mestizos in Mexico

In Mexico, the term Mestizo (lit. mixed) is used to refer to an identity that can be defined by different criteria, ranging from ideological and cultural to ones of self-identification or physical appearance. Because of this, estimates of the number of Mestizos in Mexico vary from around 40% of the population to the practical totality of the population (including White Mexicans) which does not belong to the indigenous minorities of the country.[1][2][3][4][5]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| est. 60–107 million (40–90% of population) Varies depending on the criteria used | |

| Languages | |

| Mexican Spanish and minority languages | |

| Religion | |

| Roman Catholicism, Protestantism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indigenous Mexicans, White Mexicans, Afro-Mexicans, Asian Mexicans |

The meaning of the word Mestizo has changed over time. The word was originally used in the colonial era to refer to individuals who were of half Spanish and half Amerindian ancestry. While the caste system and racial classifications were officially abandoned once Mexico achieved its independence, the label mestizo was still used in academic circles: now to refer to all the people who were mixed race. It was in those academic circles that the "Mestizaje" or "Cosmic Race" ideology was created, the ideology asserted that Mestizos are the result of the mixing of all the races and that all of Mexico's population must become Mestizo so Mexico can finally achieve prosperity. After the Mexican Revolution the government, on its attempts to create an unified Mexican identity with no racial distinctions adopted and actively promoted the "Mestizaje" ideology, by 1930 racial identities other than "Indigenous" disappeared from the Mexican census, however at an institutional level all Mexicans who did not speak indigenous languages, including European Mexicans, were now considered to be Mestizos, transforming what once was a racial identity into a national one.[1]

In consequence, today people of very different phenotypes make up the Mestizo population in Mexico independently of whether they are mixed race or not.[5] However, since the term carries a variety of socio-cultural, economic, racial, and genetic meanings, estimates of the Mexican Mestizo population vary widely. According to the Encyclopædia Britannica, which uses as base the results of the 1921 census, between one half and two thirds of the Mexican population is Mestizo.[6] Considering "Mestizaje" is the national ideology of Mexico, this means all Mexicans who are not indigenous and partake in the nation's culture could be considered "Mestizo" by virtue of them being culturally Mexican regardless of their racial background, i.e. the practical totality of the population which is not indigenous.[1] Paradoxically, the word Mestizo has long been dropped from popular Mexican vocabulary, with the word even having pejorative connotations,[7] which further complicates attempts to quantify Mestizos via self-identification. In recent times, modern academics have challenged the Mestizaje concept, on the grounds that historical census data shows that marriages between people of different races were rare[8] and that rather than ending racism, the ideology has incentivated it as it does negate the existence of the multiple ethnic groups and cultures that coexist in Mexico.[9]

History

The exact date on which the term Mestizo and the caste system as a whole were introduced to Mexico is not known, however, the earliest surviving records that categorized people by different "qualities" (as castes were known in early colonial Mexico) are church birth and marriage records from the late 18th century.[10] Back then there was an extensive caste system which assigned a different caste name for each possible racial combination, thus unlike definitions of "Mestizo" that would appear later, in these records "Mestizo" referred strictly to people who were of half Spanish and half indigenous ancestry. The same system is present in the first ever national population census of New Spain made in 1793, on which besides "Mestizo" the classification "castizo", "pardo", "mulatto", "zambo" etc. are present and are referred as a whole as "castes".[11] After independence the caste system and racial censuses were legally abandoned which led to academics who reviewed and republished the census figures to refer to the "castes" collective simply as "Mestizos".[12]

Recently, a number of historians have explicitly questioned the actual existence of this phenomenon, considering it a fabrication of Historians starting from the 1940s. Pilar Gonzalbo, in her study "The trap of the Caste", discards, on the basis of a careful revision of sources, the idea of the existence of a Caste society in New Spain, understood as a "social organization based on the race and supported by coercive power". Joanne Rappaport, in his book on New Granada, rejects the caste system as an interpretative framework for that time, discussing both the legitimacy of a model valid for the entire colonial world and the usual association between "caste" and "race". In that same sense, the contribution of Berta Ares on the Peruvian case – the other great American viceroyalty – is going to review the term "Caste", its uses and possible meanings, returning to resume the sources, from employment in the peninsula to the Peruvian case and from the 16th to the 18th centuries. He can thus demonstrate his scanty use on the part of the virreinal authorities during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which would put into question such a period as the configuration and completeness of the "system". In the eighteenth century, its use would continue to be scarce and would normally appear in the plural, characterized by an ambiguity about who they were considered or not as caste: the word did not refer exclusively to the sectors of the population of mixed descent, but also to Spaniards and Indians, and appeared in addition to many other terms (commoners, nations, classes etc.).

As a whole, these recent contributions, which question the existence of a Caste system and review the use of Castes(s) and other terms in the sources, open new perspectives on the operability of these concepts as social practices in the colonial world. Discarding, or at least not assuming, the idea of the existence of a stable and coherent system, allows us to avoid getting stuck in an epistemological framework that limits and biases our interpretation, as indicated by the use of Gonzalbo's "trap" and explicit Rappaport in its conclusion.Berta Ares tells us to ask ourselves, then, whether "a society of caste existed" really or if we would be rather in the face of a construct of the historians of the 20th century. From that question my contribution is born, which also retakes a track left by Pilar Gonzalbo when he states: "In the twentieth century, the prestige of authors such as Angel Rosenblat and Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán, who unreservedly admitted the concept of society of caste, has determined the perpetuation of a myth of social stratification based on race".[13]

The aforementioned, new definition of “Mestizo” would be the one used in the 1921 census (the second nationwide census that included a comprehensive racial classification in Mexico's history). Made right after the consummation of the Mexican revolution, the social context on which this census was made makes it particularly unique, as the government of the time was in the process of rebuilding the country and was looking forward to uniting all Mexicans under a single national identity, the government found the identity it was looking for in the “mestizaje” or “cosmic race” ideology forged mainly by prominent academics and politicians José Vasconcelos and Manuel Gamio. The ideology asserted that Mexican Mestizos were the result of the mixing of all the races, obtaining the best qualities of each and that for Mexico to finally achieve prosperity all of the country's population had to become Mestizo. By the 1930 census, the racial classifications of “White” and “Mestizo” disappeared, however implicitly all Mexicans who did not speak an indigenous language were now considered to be Mestizos.[1] The government also implemented cultural policies designed to "help" indigenous peoples achieve the same level of progress as the Mestizo society, eventually assimilating indigenous peoples completely to mainstream Mexican culture, aiming to solve the "Indian problem" by transforming indigenous communities into Mestizo ones.[3]

While for most of its history the concept of Mestizo and Mestizaje has been lauded by Mexico's intellectual circles, in recent times the concept has been target of criticism, with its detractors claiming that it delegitimizes the importance of race in Mexico under the idea of "(racism) not existing here (in Mexico), as everybody is Mestizo."[15] In general, the authors conclude that Mexico introducing a real racial classification and accepting itself as a multicultural country opposed to a monolithic Mestizo country would bring benefits to the Mexican society as a whole.[9] Other criticisms claim that the ideology couldn't homogenize the different races that lived within Mexico because at its root, the ideology sought the “whitening” of Indigenous peoples and never the "indianization" of Whites[16] or that it has accidentally erased from history minority ethnic groups such as Afro-Mexicans.[17] In general, the authors conclude that Mexico introducing a real racial classification and accepting itself as a multicultural country opposed to a monolithic Mestizo country would bring benefits to the Mexican society as a whole.[9]

Outside of Mexico, the word "mestizo" is still used to refer to persons with mixed Indigenous and European ancestry. This usage does not conform to the modern Mexican usage of the word where a person of pure indigenous genetic heritage would be considered mestizo either by rejecting his indigenous culture or by not speaking an indigenous language,[7] and a person with a very low or without any percentage of indigenous genetic heritage would be considered fully indigenous either by speaking an indigenous language or by identifying with a particular indigenous cultural heritage.[2] In some regions of Mexico such as the Yucatán peninsula the word Mestizo is used to refer to the Maya-speaking populations living in traditional communities because during the caste war of the late 19th century those Maya who did not join the rebellion were classified as mestizos. In Chiapas, the term Ladino is used instead of Mestizo.[7]

Overall, the term "Mestizo" is no longer in wide use in contemporary Mexican society, with its use being limited to social and cultural studies when referring to the non-indigenous part of the Mexican population. The word has somewhat pejorative connotations and most of the Mexican citizens who would be defined as mestizos in the sociological literature would probably self-identify as Mexicans,[7] which complicate their quantification via self-identification. This is a direct contrast to ethno racial terms such as “Indian” “White” “Black” etc. who are still prominent in everyday social interactions in Mexico, it is not exactly known why this happened but is attributed to Mexicans simply favoring the use of “static” ethnic labels over “fluid” ones.[9]

Genetic studies

Population genetics

Mexicans who are biologically Mestizos are primarily of European and Native American ancestry. The third largest component is African, partly a legacy of slavery in New Spain (which saw the importation of possibly up to 100,000[19][20] black slaves). However, geneticists theorize that in the central valleys of Mexico which did not have any presence of slaves, African admixture may have come from Spanish colonists and not African slaves themselves, as said ancestry is predominantly of North African origin.[21] Depending on the region, some may have small traces of Asian admixture due to the thousands of Filipinos and Chinos (Asian slaves of diverse origin, not just Chinese) that arrived on the Nao de China. More recent Asian immigration (specifically Chinese) may help explain the comparatively high Asian contribution in Northwest Mexico (i.e., Sonora). The INMEGEN report also notes that on average, the largest genetic component of the self-identified Mestizo Mexicans is indigenous, while African and Asian genetic markers are diminishing with each generation and will continue to do so without new migration.[20] For example, there were an estimated 600,000 Afromestizos or Mestizos of significant African descent at the end of the colonial period which roughly amounted to 10% of the population (Euromestizos and indomestizos were estimeted at 1,000,000 and 600,000 respectively)[22] while as of 2015, the number of self identified Afro-Mexicans was 1.38 million (1.2% of the population).[23]

The Mestizaje ideology, which has blurred the lines of race at an institutional level has also had a significative influence in genetic studies done in Mexico:[24] As the criteria used in studies to determine if a Mexican is Mestizo or indigenous often lies in cultural traits such as the language spoken instead of racial self-identification or a phenotype-based selection there are studies on which populations who are considered to be Indigenous per virtue of the language spoken such as Nahua peoples from the state of Veracruz show a higher degree of European genetic admixture than the one populations considered to be Mestizo report in other studies.[25] The opposite also happens, as there instances on which populations considered to be Mestizo show genetic frequencies very similar to continental European peoples in the case of Mestizos from the state of Durango[26] or to European derived Americans in the case of Mestizos from the state of Jalisco.[27]

Autosomal studies

Genetic research in the Mexican population is numerous and has yielded a myriad of different results, it is not rare that different genetic studies done in the same location vary greatly, clear examples of said variation are the city of Monterrey in the state of Nuevo León, which, depending of the study presents an average European ancestry ranging from 38%[28] to 78%,[29] and Mexico City, whose European admixture ranges from as little as 21%[30] to 70%,[31] reasons behind such variation may include the socioeconomic background of the analyzed samples[31] as well as the criteria to recruit volunteers: some studies only analyze Mexicans who self-identify as Mestizos,[32] others may classify the entire Mexican population as "mestizo",[33] other studies may do both, such as the 2009 genetic study published by the INMEGEN (Mexico's National Institute of Genomic Medicine), which states that 93% of the Mexican population is Mestizo with the remaining being Amerindian, however for its study the institute only recruited people who explicitly self-identified as mestizos.[20] Finally there are studies who avoid using any racial classification whatsoever, including in them any person that self-identifies as Mexican, these studies are the ones who usually report the highest European admixture for a given location.[34]

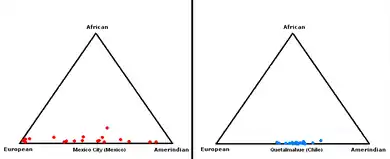

Regardless of the criteria used all the autosomal DNA studies made coincide on there being a significant genetic variation depending on the region analyzed, with southern Mexico having prevalent Amerindian and small but higher than average African genetic contributions, the central region of Mexico showing a balance between Amerindian and European components,[35] and the latter gradually increasing as one travels northwards and westwards, where European ancestry becomes the majority of the genetic contribution[36] up until cities located at the Mexico–United States border, where studies suggest there is a significant resurgence of Amerindian and African admixture.[37]

A 2006 study conducted by Mexico's National Institute of Genomic Medicine (INMEGEN), which genotyped 104 samples, reported that mestizo Mexicans are 59% European, 35% "Asian" (primarily Amerindian), and 5% Other.[38]

Research conducted by the country's Instituto Nacional de Medicina Genómica (INMEGEN) has found that Mexico's Mestizo population is not uniform in its genetic composition, with there being significant regional variation.[20] For example, mestizos of primarily European ancestry predominate in Sonora, while mestizos from the central region (Guanajuato and Zacatecas) have a more even split between indigenous and European.[20] The highest African contribution in the twelve participating states (picked to be representative of the major regions of Mexico) was found in Guerrero and Veracruz, while the highest Asian contribution was found in Guerrero and Sonora.[20]

A study made by the University College London which included the countries of Mexico, Brazil, Chile & Colombia, and was made with collaboration of each countries' antrophology and genetics institutes reported the genetic ancestry of Mexican Mestizos was 56% Native American, 37% European and 5% African, making Mexico, after Peru and Bolivia, the country with the highest Amerindian ancestry out of the five sample populations. Additionally, different phenotypical traits were analyzed, with the study determining that the frequency of blond hair and light eyes in Mexicans was of 18.5% and 28.5% respectively,[39] making Mexico also the country with the second highest frequency of blond hair in the study. The reason behind such discrepancy between phenotypical traits and genetic ancestry may lie in the low African contribution found within the Mexican population relative to Brazil and Colombia. In addition, the samples used in Mexico's case were highly unproportional, as the northern and western regions of Mexico contain 45% of Mexico's population, but no more than 10% of the samples used in the study came from the states located in these regions. For the most part, the rest of the samples hailed from Mexico City and southern Mexican states.[40]

Additional studies suggests a tendency relating a higher European admixture with a higher socioeconomic status and a higher Amerindian ancestry with a lower socioeconomic status: a study made exclusively on low income Mestizos residing in Mexico City found the mean admixture to be 0.590, 0.348, and 0.062 for Amerindian, European and African respectively whereas the European admixture increased to an average of around 70% on mestizos belonging to a higher socioeconomical level.[31] In 2011, an autosomal dna study was conducted in Mexico city, with 1,310 samples, showing the average proportion of Native American, European, and African ancestry for the population to be 64%, 32%, and 4% respectively. Additional autosomal dna studies conducted on people from Mexico city show a predominate Native American background, with Native American ancestry ranging from 61–69% in 5 different studies. The number of people sampled in these studies ranged from 66 to 984 people.[41][42][43][44][45] One outlier study showed a predominate European background for mestizos of Mexico City, showing 57% European ancestry, 40% Native American ancestry, and 3% African ancestry. The sample population for this study however, was only 19 people.[18]

MtDna and Y DNA studies

A 2012 study published by the Journal of Human Genetics Y chromosomes found the deep paternal ancestry of the Mexican mestizo population to be predominately European (64.9%), followed by Amerindian (30.8%) and Asian (1.2%).[33] The European Y chromosome was more prevalent in the north and west (66.7–95%) and Native American ancestry increased in the center and southeast (37–50%), the African ancestry was low and relatively homogeneous (0–8.8%).[33] The states that participated in this study where Aguascalientes, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Durango, Guerrero, Jalisco, Oaxaca, Sinaloa, Veracruz and Yucatán.[33] The largest amount of chromosomes found were identified as belonging to the haplogroups from Western Europe, East Europe and Eurasia, Siberia and the Americas and Northern Europe with relatively smaller traces of haplogroups from Central Asia, South-east Asia, South-central Asia, Western Asia, The Caucasus, North Africa, Near East, East Asia, North-east Asia, South-west Asia and the Middle East.[33] Also a study published in 2011 on Mexican Mitochondrial DNA found that maternal ancestry was predominately Native American (85–90%), with a minority having European (5–7%) or African (3–5%) mtDNA.[46]

An autosomal ancestry study performed on Mexico city reported that the European ancestry of Mexicans was 52% with the rest being Amerindian and a small African contribution, additionally maternal ancestry was analyzed, with 47% being of European origin. The only criteria for sample selection was that the volunteers self-identified as Mexicans.[34]

Culture

In colonial period, the people was said that some mestizos lived as Indians and other mestizos lived as creoles, from these a culture completely different from the indigenous and Spanish developed, the society of New Spain was built as a mixture of indigenous, European, African and Asian syncretism. After the independence of Mexico, was estimated between 50% -60% of the country's population was indigenous, 18% -22% were Creoles and around 1% were black; the rest of the population (21% -25%) were considered Mestizos and were an important part of the secessionist movement of the territory before the Spanish crown.[12] The Mestizo culture is an important element of national identity, Mestizo culture was separated the Spanish culture from the towns of Mexico.

Mestizo music

The 'banda de viento' are musical ensembles in which wind instruments, mostly brass, and percussion are performed.

The history about music dates back to the mid-nineteenth century with the arrival of piston brass instruments, when communities tried to imitate military bands. The first bands were formed in all Mexico. In each town in the different territories there is a certain type of band or band of winds, whether traditional, private or municipal. The Zacatecan tamborazo is an example, others are Sinaloa tamborazo, bands of Oaxaca, bands of Michoacán and band of Tlayacapan.

Mestizo cuisine

Mestizo cuisine is a mixed flavors by Indigenous meals as corn, chili, tomato, potato, fruits and brushes from the Americas and meats from domesticated animals as the turkey, quail and fish with European meals introduced a number of foods, the most important of which were meats from other domesticated animals (beef, pork, chicken, goat, and sheep), dairy products (especially cheese and milk), and rice. While the Sephardic foods initially tried to impose their own diet on the country with Asian and African influences were also introduced into the indigenous cuisine during this era.[47]

Mexican cuisine is an important aspect of the culture, social structure and popular traditions of Mestizo Mexico. The most important example of this connection is the use of mole for special occasions and holidays, now in all regions of the country. For this reason and others, traditional Mexican cuisine was inscribed in 2010 on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[48]

Notable Mestizo people

Mestizos with European roots

Porfirio Díaz, ex-president and military leader.

Porfirio Díaz, ex-president and military leader. Emiliano Zapata, military leader.

Emiliano Zapata, military leader..jpg.webp) Francisco Villa, military leader.

Francisco Villa, military leader. Mario Moreno Cantinflas, actor.

Mario Moreno Cantinflas, actor. María Félix, actress and singer.

María Félix, actress and singer. Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, expresident and politician.

Gustavo Díaz Ordaz, expresident and politician. Octavio Paz, writer and Nobel laureated.

Octavio Paz, writer and Nobel laureated. Carmen Salinas, actress and politician.

Carmen Salinas, actress and politician. Monica Miguel, writer and actress.

Monica Miguel, writer and actress. Mario Molina, chemist and Nobel laureate.

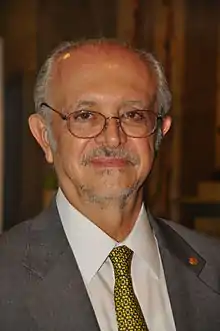

Mario Molina, chemist and Nobel laureate..jpg.webp) Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, politician.

Cuauhtémoc Cárdenas, politician._(cropped).jpg.webp) Andrés Manuel López Obrador, current president of Mexico.

Andrés Manuel López Obrador, current president of Mexico..jpg.webp) Juan Gabriel, singer and actor.

Juan Gabriel, singer and actor..jpg.webp) Patricia Reyes Spíndola, writer and actress.´

Patricia Reyes Spíndola, writer and actress.´.jpg.webp) Felipe Calderón, ex-president and politician.

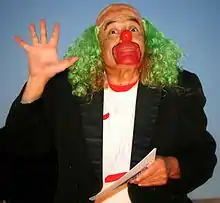

Felipe Calderón, ex-president and politician. Víctor Trujillo, journalist and clown.

Víctor Trujillo, journalist and clown._(cropped).jpg.webp) Lila Downs, singer.

Lila Downs, singer. Adriana Paz, dancer and actress.

Adriana Paz, dancer and actress.

Mestizos with African roots

Vicente Guerrero, ex-president and military leader.

Vicente Guerrero, ex-president and military leader. Juan Álvarez, ex-president and military leader.

Juan Álvarez, ex-president and military leader. Alejandra Robles, singer.

Alejandra Robles, singer. Kalimba, singer.

Kalimba, singer._(cropped).jpg.webp) Giovani dos Santos, soccer player.

Giovani dos Santos, soccer player.

Mestizos with Asian roots

Alejandro Gómez Maganda politician.

Alejandro Gómez Maganda politician..jpg.webp) Luis Nishizawa painter and academic.

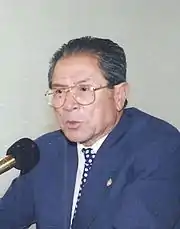

Luis Nishizawa painter and academic. Jesús Kumate Rodríguez, academic and physician.

Jesús Kumate Rodríguez, academic and physician. Ana Gabriel, singer.

Ana Gabriel, singer.

See also

References and footnotes

- en el censo de 1930 el gobierno mexicano dejó de clasificar a la población del país en tres categorías raciales, blanco, mestizo e indígena, y adoptó una nueva clasificación étnica que distinguía a los hablantes de lenguas indígenas del resto de la población, es decir de los hablantes de español. Archived 2013-08-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Knight, Alan (1990). "Racism, Revolution and indigenismo: Mexico 1910–1940". In Graham, Richard (ed.). The Idea of Race in Latin America, 1870–1940. Austin: University of Texas Press. pp. 73. ISBN 978-0-292-73856-0.

- Bartolomé, Miguel Alberto (1996). "Pluralismo cultural y redefinicion del estado en México" (PDF). Coloquio sobre derechos indígenas. Oaxaca: IOC. p. 5. ISBN 978-968-6951-31-8.

- "El impacto del mestizaje en México", “Investigación y Ciencia”, Spain, October 2013. Retrieved on 01 June 2017.

- Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (August 2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" [Ethnic Composition of the Three Cultural Areas of the American Continent at the Beginning of the 21st Century]. Convergencia (in Spanish). 12 (38): 185–232.

- "Mexico- Ethnic groups". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 October 2016.

- Bartolomé, Miguel Alberto (1996). "Pluralismo cultural y redefinicion del estado en México" (PDF). Coloquio sobre derechos indígenas. Oaxaca: IOC. p. 2. ISBN 978-968-6951-31-8.

- Federico Navarrete (2016). Mexico Racista. Penguin Random house Grupo Editorial Mexico. p. 86. ISBN 9786073143646. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- "El mestizaje en Mexico" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-01. Retrieved 2017-06-20.

- San Miguel, G. (November 2000). "Ser mestizo en la nueva España a fines del siglo XVIII: Acatzingo, 1792" [To be 'mestizo' in New Spain at the end of the XVIII th century. Acatzingo, 1792]. Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales. Universidad Nacional de Jujuy (in Spanish) (13): 325–342.

- Sherburne Friend Cook; Woodrow Borah (1998). Ensayos sobre historia de la población. México y el Caribe 2. Siglo XXI. p. 223. ISBN 9789682301063. Retrieved September 12, 2017.

- Lerner, Victoria (1968). "Consideraciones sobre la población de la Nueva España (1793-1810): Según Humboldt y Navarro y Noriega" [Considerations on the population of New Spain (1793-1810): According to Humboldt and Navarro and Noriega]. Historia Mexicana (in Spanish). 17 (3): 327–348. JSTOR 25134694.

- Giraudo, Laura (14 June 2018). "Casta(s), 'sociedad de castas' e indigenismo: la interpretación del pasado colonial en el siglo XX" [Casta(s), the 'society of castes' and indigenismo: the interpretation of the colonial past in the 20th century]. Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos (in Spanish). doi:10.4000/nuevomundo.72080.

- Moreno Figueroa, Mónica G. (August 2016). "El archivo del estudio del racismo en México" [An Archive of the Study of Racism in Mexico]. Desacatos (in Spanish) (51): 92–107.

- Federico Navarrete (2016). Mexico Racista. Penguin Random house Grupo Editorial Mexico. p. 89. ISBN 9786073143646. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

- Jiménez, Arturo (8 August 2011). "El Estado no reconoce a los afromexicanos; con los indígenas, son los más discriminados" [The State does not recognize Afro-Mexicans; with indigenous people, they are the most discriminated against]. La Jornada (in Spanish).

- Wang, Sijia; Ray, Nicolas; Rojas, Winston; Parra, Maria V.; Bedoya, Gabriel; Gallo, Carla; Poletti, Giovanni; Mazzotti, Guido; Hill, Kim; Hurtado, Ana M.; Camrena, Beatriz; Nicolini, Humberto; Klitz, William; Barrantes, Ramiro; Molina, Julio A.; Freimer, Nelson B.; Bortolini, Maria Cátira; Salzano, Francisco M.; Petzl-Erler, Maria L.; Tsuneto, Luiza T.; Dipierri, José E.; Alfaro, Emma L.; Bailliet, Graciela; Bianchi, Nestor O.; Llop, Elena; Rothhammer, Francisco; Excoffier, Laurent; Ruiz-Linares, Andrés (21 March 2008). "Geographic Patterns of Genome Admixture in Latin American Mestizos". PLOS Genetics. 4 (3): e1000037. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000037. PMC 2265669. PMID 18369456.

- Rayna Bailey (2010). Immigration and Migration. Infobase Publishing. p. 93. ISBN 9780816071067. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- Silva-Zolezzi, Irma; Hidalgo-Miranda, Alfredo; Estrada-Gil, Jesus; Fernandez-Lopez, Juan Carlos; Uribe-Figueroa, Laura; Contreras, Alejandra; Balam-Ortiz, Eros; del Bosque-Plata, Laura; Velazquez-Fernandez, David; Lara, Cesar; Goya, Rodrigo; Hernandez-Lemus, Enrique; Davila, Carlos; Barrientos, Eduardo; March, Santiago; Jimenez-Sanchez, Gerardo (26 May 2009). "Analysis of genomic diversity in Mexican Mestizo populations to develop genomic medicine in Mexico". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (21): 8611–8616. Bibcode:2009PNAS..106.8611S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903045106. PMC 2680428. PMID 19433783.

- "Genoma destapa diferencias de mexicanos". 2009-06-06.

- "Chapter 2". Historia de Mexico, Legado Historico Y Pasado Reciente. Table 2.1: Pearson Educación. 2004. ISBN 9789702605232. Retrieved October 1, 2016.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Estados Unidos Mexicanos" (PDF). INEGI. p. 77. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- Schwartz-Marín, Ernesto; Silva-Zolezzi, Irma (December 2010). "'The Map of the Mexican's Genome': overlapping national identity, and population genomics". Identity in the Information Society. 3 (3): 489–514. doi:10.1007/s12394-010-0074-7. S2CID 144786737.

- Buentello‐Malo, Leonora; Peñaloza‐Espinosa, Rosenda I.; Salamanca‐Gómez, Fabio; Cerda‐Flores, Ricardo M. (2008). "Genetic admixture of eight Mexican indigenous populations: Based on five polymarker, HLA-DQA1, ABO, and RH loci". American Journal of Human Biology. 20 (6): 647–650. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20747. PMID 18770527. S2CID 28766515.

- Sosa-Macías, Martha; Elizondo, Guillermo; Flores-Pérez, Carmen; Flores-Pérez, Janet; Bradley-Alvarez, Francisco; Alanis-Bañuelos, Ruth E.; Lares-Asseff, Ismael (May 2006). "CYP2D6 Genotype and Phenotype in Amerindians of Tepehuano Origin and Mestizos of Durango, Mexico". The Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 46 (5): 527–536. doi:10.1177/0091270006287586. PMID 16638736. S2CID 41443294.

- Valdez-Velazquez, Laura L.; Mendoza-Carrera, Francisco; Perez-Parra, Sandra A.; Rodarte-Hurtado, Katia; Sandoval-Ramirez, Lucila; Montoya-Fuentes, Héctor; Quintero-Ramos, Antonio; Delgado-Enciso, Ivan; Montes-Galindo, Daniel A.; Gomez-Sandoval, Zeferino; Olivares, Norma; Rivas, Fernando (16 December 2010). "Renin gene haplotype diversity and linkage disequilibrium in two Mexican and one German population samples". Journal of the Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System. 12 (3): 231–237. doi:10.1177/1470320310388440. PMID 21163863. S2CID 26481247.

- Martinez-Fierro, Margarita L; Beuten, Joke; Leach, Robin J; Parra, Esteban J; Cruz-Lopez, Miguel; Rangel-Villalobos, Hector; Riego-Ruiz, Lina R; Ortiz-Lopez, Rocio; Martinez-Rodriguez, Herminia G; Rojas-Martinez, Augusto (September 2009). "Ancestry informative markers and admixture proportions in northeastern Mexico". Journal of Human Genetics. 54 (9): 504–509. doi:10.1038/jhg.2009.65. PMID 19680268. S2CID 13714976.

- Cerda-Flores, Ricardo; Kshatriya, Gautam; Barton, Sara; Leal-Garza, Carlos; Garza-Chapa, Raul; Schull, William; Chakraborty, Ranajit (27 January 2014). "Genetic Structure of the Populations Migrating from San Luis Potosi and Zacatecas to Nuevo León in Mexico". Human Biology. 63 (3): 309–27. JSTOR 41464178. PMID 2055589.

- Luna-Vazquez, A; Vilchis-Dorantes, G; Paez-Riberos, L.A; Muñoz-Valle, F; González-Martin, A; Rangel-Villalobos, H (September 2003). "Population data of nine STRs of Mexican-Mestizos from Mexico City". Forensic Science International. 136 (1–3): 96–98. doi:10.1016/s0379-0738(03)00254-8. PMID 12969629.

- Lisker, Rubén; Ramírez, Eva; González‐Villalpando, Clicerio; Stern, Michael P. (1995). "Racial admixture in a Mestizo population from Mexico City". American Journal of Human Biology. 7 (2): 213–216. doi:10.1002/ajhb.1310070210. PMID 28557218. S2CID 8177392.

- J.K. Estrada; A. Hidalgo-Miranda; I. Silva-Zolezzi; G. Jimenez-Sanchez. "Evaluation of Ancestry and Linkage Disequilibrium Sharing in Admixed Population in Mexico". ASHG. Archived from the original on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 18 July 2012.

- Martínez-Cortés, Gabriela; Salazar-Flores, Joel; Gabriela Fernández-Rodríguez, Laura; Rubi-Castellanos, Rodrigo; Rodríguez-Loya, Carmen; Velarde-Félix, Jesús Salvador; Franciso Muñoz-Valle, José; Parra-Rojas, Isela; Rangel-Villalobos, Héctor (September 2012). "Admixture and population structure in Mexican-Mestizos based on paternal lineages". Journal of Human Genetics. 57 (9): 568–574. doi:10.1038/jhg.2012.67. PMID 22832385. S2CID 2876124.

- Price, Alkes L.; Patterson, Nick; Yu, Fuli; Cox, David R.; Waliszewska, Alicja; McDonald, Gavin J.; Tandon, Arti; Schirmer, Christine; Neubauer, Julie; Bedoya, Gabriel; Duque, Constanza; Villegas, Alberto; Bortolini, Maria Catira; Salzano, Francisco M.; Gallo, Carla; Mazzotti, Guido; Tello-Ruiz, Marcela; Riba, Laura; Aguilar-Salinas, Carlos A.; Canizales-Quinteros, Samuel; Menjivar, Marta; Klitz, William; Henderson, Brian; Haiman, Christopher A.; Winkler, Cheryl; Tusie-Luna, Teresa; Ruiz-Linares, Andrés; Reich, David (June 2007). "A Genomewide Admixture Map for Latino Populations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 80 (6): 1024–1036. doi:10.1086/518313. PMC 1867092. PMID 17503322.

- Hernández-Gutiérrez, S.; Hernández-Franco, P.; Martínez-Tripp, S.; Ramos-Kuri, M.; Rangel-Villalobos, H. (30 June 2005). "STR data for 15 loci in a population sample from the central region of Mexico". Forensic Science International. 151 (1): 97–100. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2004.09.080. PMID 15935948.

- Cerda‐Flores, Ricardo M.; Villalobos‐Torres, Maria C.; Barrera‐Saldaña, Hugo A.; Cortés‐Prieto, Lizette M.; Barajas, Leticia O.; Rivas, Fernando; Carracedo, Angel; Zhong, Yixi; Barton, Sara A.; Chakraborty, Ranajit (2002). "Genetic admixture in three mexican mestizo populations based on D1S80 and HLA-DQA1 Loci". American Journal of Human Biology. 14 (2): 257–263. doi:10.1002/ajhb.10020. PMID 11891937. S2CID 31830084.

- Loya Méndez, Yolanda; Reyes Leal, G; Sánchez González, A; Portillo Reyes, V; Reyes Ruvalcaba, D; Bojórquez Rangel, G (1 February 2015). "Variantes genotípicas del SNP-19 del gen de la CAPN 10 y su relación con la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 en una población de Ciudad Juárez, México" [SNP-19 genotypic variants of CAPN 10 gene and its relation to diabetes mellitus type 2 in a population of Ciudad Juarez, Mexico]. Nutrición Hospitalaria (in Spanish). 31 (2): 744–750. doi:10.3305/nh.2015.31.2.7729. PMID 25617558.

- J.K. Estrada; A. Hidalgo-Miranda; I. Silva-Zolezzi; G. Jimenez-Sanchez. "Evaluation of Ancestry and Linkage Disequilibrium Sharing in Admixed Population in Mexico". ASHG. Archived from the original on September 13, 2014. Retrieved July 18, 2012.

- "Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals" table 1, Plosgenetics, 25 September 2014. Retrieved on 9 May 2017.

- Ruiz-Linares, Andrés; Adhikari, Kaustubh; Acuña-Alonzo, Victor; Quinto-Sanchez, Mirsha; Jaramillo, Claudia; Arias, William; Fuentes, Macarena; Pizarro, María; Everardo, Paola; de Avila, Francisco; Gómez-Valdés, Jorge; León-Mimila, Paola; Hunemeier, Tábita; Ramallo, Virginia; Silva de Cerqueira, Caio C.; Burley, Mari-Wyn; Konca, Esra; de Oliveira, Marcelo Zagonel; Veronez, Mauricio Roberto; Rubio-Codina, Marta; Attanasio, Orazio; Gibbon, Sahra; Ray, Nicolas; Gallo, Carla; Poletti, Giovanni; Rosique, Javier; Schuler-Faccini, Lavinia; Salzano, Francisco M.; Bortolini, Maria-Cátira; Canizales-Quinteros, Samuel; Rothhammer, Francisco; Bedoya, Gabriel; Balding, David; Gonzalez-José, Rolando (25 September 2014). "Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals". PLOS Genetics. 10 (9): e1004572. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004572. PMC 4177621. PMID 25254375.

- Martinez-Marignac, Veronica L.; Valladares, Adan; Cameron, Emily; Chan, Andrea; Perera, Arjuna; Globus-Goldberg, Rachel; Wacher, Niels; Kumate, Jesús; McKeigue, Paul; O'Donnell, David; Shriver, Mark D.; Cruz, Miguel; Parra, Esteban J. (1 February 2007). "Admixture in Mexico City: implications for admixture mapping of Type 2 diabetes genetic risk factors". Human Genetics. 120 (6): 807–819. doi:10.1007/s00439-006-0273-3. PMID 17066296. S2CID 18304529.

- Juárez-Cedillo, Teresa; Zuñiga, Joaquín; Acuña-Alonzo, Victor; Pérez-Hernández, Nonanzit; Rodríguez-Pérez, José Manuel; Barquera, Rodrigo; Gallardo, Guillermo J.; Sánchez-Arenas, Rosalinda; García-Peña, Maria del Carmen; Granados, Julio; Vargas-Alarcón, Gilberto (June 2008). "Genetic admixture and diversity estimations in the Mexican Mestizo population from Mexico City using 15 STR polymorphic markers". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 2 (3): e37–e39. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2007.08.017. PMID 19083813.

- Kosoy, Roman; Nassir, Rami; Tian, Chao; White, Phoebe A.; Butler, Lesley M.; Silva, Gabriel; Kittles, Rick; Alarcon‐Riquelme, Marta E.; Gregersen, Peter K.; Belmont, John W.; Vega, Francisco M. De La; Seldin, Michael F. (2009). "Ancestry informative marker sets for determining continental origin and admixture proportions in common populations in America". Human Mutation. 30 (1): 69–78. doi:10.1002/humu.20822. PMC 3073397. PMID 18683858.

- Rubi‐Castellanos, Rodrigo; Martínez‐Cortés, Gabriela; Francisco Muñoz‐Valle, José; González‐Martín, Antonio; Cerda‐Flores, Ricardo M.; Anaya‐Palafox, Manuel; Rangel‐Villalobos, Héctor (July 2009). "Pre‐Hispanic Mesoamerican demography approximates the present‐day ancestry of Mestizos throughout the territory of Mexico". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 139 (3): 284–294. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20980. PMID 19140185.

- Johnson, Nicholas A.; Coram, Marc A.; Shriver, Mark D.; Romieu, Isabelle; Barsh, Gregory S.; London, Stephanie J.; Tang, Hua (15 December 2011). "Ancestral Components of Admixed Genomes in a Mexican Cohort". PLOS Genetics. 7 (12): e1002410. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002410. PMC 3240599. PMID 22194699.

- Kumar, Satish; Bellis, Claire; Zlojutro, Mark; Melton, Phillip E; Blangero, John; Curran, Joanne E (2011). "Large scale mitochondrial sequencing in Mexican Americans suggests a reappraisal of Native American origins". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 11 (1): 293. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-293. PMC 3217880. PMID 21978175.

- "La cocina del virreinato". CONACULTA. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- "Traditional Mexican cuisine – ancestral, ongoing community culture, the Michoacán paradigm". UNESCO. Retrieved January 13, 2015.