Afro-Mexicans

Afro-Mexicans (Spanish: afromexicanos), also known as Black Mexicans (Spanish: mexicanos negros),[2] are Mexicans who have a predominant heritage from Sub-Saharan Africa[3][2] and identify as such. As a single population, Afro-Mexicans includes individuals descended from black slaves brought to Mexico during the colonial era in the transatlantic African slave trade, as well as others of more recent immigrant African descent,[3] including Afro-descended persons from neighboring English, French, and Spanish-speaking countries of the Caribbean and Central America, descendants of fugitive slaves who escaped to Mexico from the Southern United States, and to a lesser extent recent immigrants directly from Africa. Afro-Mexicans are most concentrated in specific, largely isolated communities, including the populations of the Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Guerrero, Veracruz and in some cities in northern Mexico.

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,381,853[1] (2015 intercensus) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Costa Chica of Guerrero, Costa Chica of Oaxaca, Veracruz, Greater Mexico City and small settlements in northern Mexico | |

| Languages | |

| Spanish | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Roman Catholicism, Protestantism), Afro-American religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| West Africans, Afro-Latin Americans and other Mexicans |

According to recent DNA studies, most Mexicans have a small amount of African DNA mixed into the predominant Mexican heritage gene pool, averaging to about 5% African DNA, although most of it is North African and was brought to Mexico as part of the diluted African DNA in Spanish settlers.[4] Therefore Afro-Mexican refers specifically to those Mexicans who have above-average levels of specifically West African ancestry noticeable in their phenotype.

As opposed to other Spanish-speaking countries in Latin America with visible Afro-Latino populations, the history of Africans in Mexico has been lesser known for a number of reasons. Included among these reasons were their small numbers as a proportion of the overall population of Mexico, irregular intermarriage with other Mexican ethnic groups, racism in Mexico and other Latin-American countries, and Mexico's tradition of defining itself as a "Mestizo" country. Although mestizo etymologically means "mixed", the word is widely understood with the specific meaning of "mixed Spanish and Native-Mexican”, because not all Mexicans are Mestizos. A large percentage of European Mexicans, and indigenous Mexicans reside in Mexico.

According to The Atlantic Slave Trade an estimated 200,000 enslaved Africans disembarked in New Spain, which later became modern Mexico.[5] From the beginning, the slaves, who were mostly male, intermarried with indigenous women. In other cases, Spanish colonists raped the female slaves. Spanish colonists created an elaborate racial caste system, classifying people by racial mixture. This system broke down in the very late colonial period; after Independence, the legal notion of race was eliminated.

The creation of a national Mexican identity, especially after the Mexican Revolution, emphasized Mexico's indigenous Amerindians and Spanish European heritage, excluding Africans' history and contributions from Mexico's national consciousness. Although Mexico had a significant number of African slaves during the colonial era, most of the African-descended population were absorbed into the several times larger surrounding Mestizo (mixed European/Amerindian) and indigenous populations through unions among the groups. In 1992, the Mexican government officially recognized African culture as being one of the three major influences on the culture of Mexico, the others being Spanish and Indigenous.[6]

The genetic legacy of Mexico's once significant number of colonial-era African slaves is evidenced in non-Black Mexicans as trace amounts of sub-Saharan African DNA found in the average Mexican. Evidence of this long history of intermarriage with Mestizo and indigenous Mexicans is also expressed in the fact that in the 2015 census, 64.9% (896,829) of Afro-Mexicans also identified as indigenous Amerindian Mexicans. It was also reported that 9.3% of Afro-Mexicans speak an indigenous Mexican language.[7]

About 1.2% of Mexico's population has significant African ancestry, with 1.38 million self-recognized during the 2015 Intercensus Estimate. Numerous Afro-Mexicans in the 21st century are naturalized black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean.[8] The 2015 Intercensus Estimate was the first time in which Afro-Mexicans could identify themselves as such and was a preliminary effort to include the identity before the 2020 census. The question asked on the survey was "Based on your culture, history, and traditions, do you consider yourself black, meaning Afro-Mexican or Afro-descendant?"[9] and came about following various complaints made by civil rights groups and government officials.

Some of their activists, like Benigno Gallardo, do feel their communities lack "recognition and differentiation", by what he calls "mainstream mexican culture". This, however, is mostly due to the small numbers of Afro-descendant individuals relative to the gross Mexican population, and their very defined and isolated communities,[9]

History

Enslaved Africans were brought in large numbers to Spanish America and to Mexico in particular, becoming an integral part of Mexican society. Afro-Mexicans engaged in a variety of economic activities as slaves and as free persons. Mexico never became a society based on slavery, as happened in the Anglo-American southern colonies or Caribbean islands, where plantations utilized large numbers of field slaves. At conquest, central Mexico had a large, hierarchically organized Indian population that provided largely coerced labor. Mexico's economy utilized African slave labor during the colonial period, particularly in Spanish cities as domestic workers, artisans, and laborers in textile workshops (obrajes). Although Mexico has celebrated its mixed indigenous and European roots mestizaje, Africans' presence and contributions have until recently were not part of the national discourse. Increasingly, the historical record has been revised to take account of Afro-Mexicans' long presence in Mexico.

Geographical origins and the Atlantic slave trade

Although the vast majority had their roots in Africa, not all slaves made the trip directly to New Spain, some came from other Spanish territories, particularly the Caribbean. Those from Africa belonged mainly to groups coming from Western Sudan and ethnic Bantu.

The origin of the slaves is known through various documents such as transcripts of sales. Originally the slaves came from Cape Verde and Guinea.[11] Later slaves were also taken from Angola.[12]

To decide the sex of the slaves that would be sent to the New World, calculations that included physical performance and reproduction were performed. At first half of the slaves imported were women and the other half men, but it was later realized that men could work longer without fatigue and that they yielded similar results throughout the month, while women suffered from pains and diseases more easily.[12] Later on, only one third of the total slaves were women.

From the African continent dark skinned slaves were taken; "the first true blacks were extracted from Arguin."[13] Later in the sixteenth century, black slaves came from Bran, biafadas and Gelofe (in Cape Verde). Black slaves were classified into several types, depending on their ethnic group and origin, but mostly from physical characteristics. There were two main groups. The first, called Retintos, also called swarthy, came from Sudan and the Guinean Coast. The second type were amulatados or amembrillados of lighter skin color, when compared with other blacks and were distinguishable by their yellow skin tones.[14]

The demand for slaves came in the early colonial period, especially between 1580 and 1640, when the indigenous population declined due to new infectious diseases.[15] Carlos V began to issue an increasing number of contracts (asientos) between the Spanish Crown and private slavers specifically to bring Africans to Spanish colonies. These slavers made deals with the Portuguese, who controlled the African slave market.[16] Mexico had important slave ports in the New World, sometimes holding slaves brought by Spanish before they were sent to other parts of Latin America and the Caribbean.[17]

According to the genetic testing company 23andMe, the predominant Sub-Saharan ancestry in Mexico is from the Senegambia and Guinea region.[18] This contrasts with the predominant Nigerian ancestry in the United States and parts of the Caribbean.[18]

Conquest and early colonial eras

Africans were brought to Mexico by Spanish conquerors and were auxiliaries in the conquest. One is shown in Codex Azcatitlan as part of the entourage of conqueror Hernán Cortés. In the account of the conquest of Mexico compiled by Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún, Nahua informants noted the presence of Africans with kinky, curly hair in contrast to the straight "yellow" and black hair of the Spaniards.[19] Mexican anthropologist Gonzalo Aguirre Beltrán counted six blacks who took part in the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. Notable among them was Juan Garrido, a free black soldier born in Africa, Christianized in Portugal, who participated in the conquest of Tenochtitlan and Western Mexico.[20] The slave of another conquistador, Pánfilo de Narváez, has been blamed for the transmission of smallpox to Nahuas in 1520. Early slaves were likely personal servants or concubines of their Spanish masters, who had been brought to Spain first and came with the conquistadors.[16][21]

While a number of indigenous people were enslaved during the conquest period, indigenous slavery as an institution was forbidden by the crown except in the cases of rebellion. Indigenous labor was coerced in the early period, mobilized by the encomienda, private grants to individual Spaniards, was the initial workforce, with black overseers often supervising indigenous laborers. Franciscan Toribio de Benavente Motolinia (1482-1568), who arrived in Mexico in 1524 to evangelize the Nahuas, considered blacks the "Fourth Plague" (in the manner of Biblical plagues) on Mexican Indians. He wrote "In the first years these black overseers were so absolute in their maltreatment of the Indians, over-loading them, sending them far from their land and giving them many other tasks that many Indians died because of them and at their hands, which is the worst feature of the situation."[22] In Yucatán, there were regulations attempting to prevent blacks presence in indigenous communities.[23] In Puebla, 1536 municipal regulations attempted to prevent blacks from going into the open-air market tianguis and harming indigenous women there, mandating fines and fifty lashes in the plaza.[24] In Mexico City in 1537, a number of blacks were accused of rebellion. They were executed in the main plaza (zócalo) by hanging, an event recorded in an indigenous pictorial and alphabetic manuscript.[25]

Once the military phase of conquest was completed in central Mexico, Spanish colonists in Puebla de los Angeles, which was the second largest Spanish settlement in Mexico, sought enslaved African women for domestic work, such as cooks and laundresses. Ownership of domestic slaves was a status symbol for Spaniards and the dowries of wealthy Spanish women included enslaved Africans.[26]

Legal status in the colonial era

Blacks classified as part of the "Republic of Spaniards" (República de Españoles), that is the Hispanic sector of Europeans, Africans, and mixed-race castas, while the indigenous were members of the "Republic of Indians" (República de Indios), and under the protection of the Spanish crown. Although there was coming to be an association between blackness and enslavement, there were Africans who achieved the formal status of vecino (resident, citizen), a designation of great importance in colonial society. In Puebla de los Angeles, a newly founded settlement for Spaniards, a small number black men achieved this status. One free black, the town crier Juan de Montalvo, was well established and in Puebla, with connections to the local Spanish elites. Others were known to hold land and engage in the local real estate market.[27]

Free blacks and mulattoes (descendants of Europeans and Africans) were subject to the payment of tribute to the crown, as were Indians, but in contrast to Indians, free blacks and mulattoes were subject to the jurisdiction of the Holy Office of the Inquisition. Legal freedom could be achieved by manumission, with liberty purchased by the enslaved person. A 1585 deed of emancipation (Carta de libertad) in Mexico City shows that the formerly enslaved woman, Juana, (a negra criolla, i.e., born in Mexico), paid her owner for her freedom with the help of Juana's husband Andrés Moreno. The price of liberty was the large sum of 200 gold pesos. Her former owner, Doña Inéz de León, declared that "it is my will that [Juana] shall be free now and for all time and not subject to servitude. And as such person she may and shall go in whatever parts and places she desires; and may appear in judgment and collect and receive her property and manage and administer her estate; and may make wills and codicils and name heirs and executors; and may act and dispose of her person in whatsoever a free person, born of free parents may and must do."[28]

Slave resistance

Although the vast majority of Africans did not overtly resist their enslavement,[29] a few did, contesting their condition by rebellion and fleeing masters. Black slave rebellions occurred in Mexico as in other parts of the Americas, with one in Veracruz in 1537 and another in the Spanish capital of Mexico City. Runaway slaves were called cimarrones, who mostly fled to the highlands between Veracruz and Puebla, with a number making their way to the Costa Chica region in what are now Guerrero and Oaxaca.[21][30] Runaways in Veracruz formed settlements called palenques which would fight off Spanish authorities. The most famous of these was led by Gaspar Yanga, who fought the Spanish for forty years until the Spanish recognized their autonomy in 1608, making San Lorenzo de los Negros (today Yanga) the first community of free blacks in the Americas.[21][30]

Free Black communities in colonial Mexico

By the 17th century, the free Black population already outnumbered the enslaved population, despite slavery being at its greatest extent in the colony during this time.[31] Creoles and mulattos occupied a legible social presence in Mexico by 1600. Most enslaved Africans were reportedly "from the land of Angola," who reconfigured African culture in colonial Mexico while complimenting the existing presence of creoles. Scholar Herman L. Bennet records that 17th century colonial Mexico was "home to the most diverse Black population in the Americas."[32] Mexico City, built on the ruins of the Mexica capital city of Tenochtitlán became the center for diverse communities, all of which served the wealthy Spaniards as "artisans, domestic servants, day laborers, and slaves." This population included "impoverished Spaniards, conquered but differentiated Indians, enslaved Africans (ladinos, individuals who were linguistically conversant in Castilian, and bozales, individuals directly from Guinea, or Africa, who were unable to speak Castilian), and the new hybrid populations (mestizos, mulatos, and zambos, persons with both Indian and African heritage)." Catholic Spaniards instituted ecclesiastical raids beginning in 1569 upon these communities in order to maintain order and ensure the gendered and conjugal norms that they, including persons of African descent, "could assume in the Christian commonwealth."[33]

Since there were no official census records in the 17th century, the exact size of the free Black population in Mexico remains unknown, although Bennet concludes, based on numerous sources of the period, that there was an "extensive free Black presence early in the 17th century."[34] In the 17th century, because of forced indoctrination instituted by Spanish colonizers, Christian beliefs, rituals, and practices were already becoming normalized by a substantial population of Black creoles in colonial Mexico, similar to the Indigenous and mestizo population – "it sought to distance Indians and Africans from their former collectivities, traditions, and pasts that had sanctioned their former selves. Such distancing was both a stated and implicit objective of masters and colonial authorities."[35] In 1640, the regular slave trade to colonial Mexico ended.[32]

The Mexican nationalist movement, which fueled the Mexican War of Independence from 1810 to 1821, was predicated on the ideological notion that Mexico possessed a unique cultural tradition – a notion which was denied by European imperial elites who asserted that Mexico lacked any basis for nationhood – and resulted in the purposeful erasure of a Black presence from Mexico's history. Scholar Herman L. Bennet states that "the demands of a previous political movement should no longer sanction the ideological practices that historically excluded the Black past and presently confines it to the margins of history," likening this erasure to an act of "ethnic cleansing."[36]

Afro-Mexicans and the Catholic Church

Catholicism shaped life among the vast majority of Africans in colonial society. Enslaved blacks were simultaneously members of the Christian community and chattel, private property of their owners. In general, the church did not take a stance against African slavery as institution, although Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas later in life campaigned against their forced serviture, and the second archbishop of Mexico, Alonso de Montúfar argued against it. Montúfar condemned the transatlantic slave trade and sought its cessation and viewed the benefits of incorporating Africans into Christianity as slave not equal to the cost to rending their ties to family in Africa. His pleas and condemnations were ignored.[37][38]

Church records of baptisms, marriages, burials, and of the Inquisition indicate a high level of the church's formal engagement with Africans. Enslaved and free Africans were full members of the church. As the African population was increased with the importation of unacculturated slaves (bozales), white elites became concerned with controlling slaves' behavior and maintaining Christian orthodoxy. With the establishment of the Inquisition in 1571, Africans appeared before the tribunal in disproportionate numbers. Although Frank Tannenbaum posits that the church intervened in master-slave relations for humanitarian reasons,[39] Herman L. Bennett argues that the church was more interested in regulating and controlling Africans in the religious sphere.[40] When the Spanish crown allowed bozales to be imported to its overseas territories, it saw Christian marriage as a way to control the enslaved. The church intervened in favor of enslaved individuals over the objections of their masters in marital choice and conjugal rights. Slaves learned how to shape these religious protections to challenge masters' authority through canon law, thereby undermining masters' absolute control over their enslaved property. For the church, the slaves' Christian identity was more important than their status as chattel. Baptismal and marriage records provide information about ties within the Afro-Mexican community between parents, god parents, and witnesses to the sacraments.[41]

Blacks and afromestizos formed and joined religious confraternities, lay brotherhoods under the supervision of the church, which became religious and social spaces to reinforce ties of individuals to larger community. These organized groups of lay men and women, were sanctioned by the Roman Catholic Church, gave their activities legitimacy in Spanish colonial society. These black confraternities were often funded by Spaniards and by the church hierarchy.,[43] were actually largely supported by Spaniards, going so far as to even fund many of them.[44] And although this support of the confraternities on the part of Spaniards and the Church was indeed an attempt to maintain moral control over the Black African population,[45] the members of the confraternities were able to use these brotherhoods and sisterhoods to maintain and develop their existing identities. A notable example of this is the popularity of choosing African saints, such as St. Efigenia, as the patron of the confraternity, a clear claim of African legitimacy for all Black Africans.[46]

African descent people found in these confraternities ways to maintain parts of their African culture alive through the use of what was socially available to them. Particularly in the baroque Christianity popular at the time and the festivals that took place in this spiritual environment, mainly public religious festivals. This fervor culminated in acts of flagellation, especially around the time of holy week, as a sign of great humility and willing suffering, which in turn, brought an individual closer to Jesus. This practice would eventually diminish and face criticism from Bishops due to the fact that often the anonymity and violent nature of this public act of piety could lead, and may have led, to indiscriminate violence. The participation in processions are another quite important and dramatic way that these confraternities expressed their piety. This was a way for the Black community to show off their material wealth that had been acquired through the confraternity, usually in the form of saint statues, candles, carved lambs with silver diadems, and other various valuable religious artifacts.[47]

The use of an African female saint, St Ephigenia, is also a claim to the legitimacy of a distinctly female identity.[48] This is significant because the Afro-Mexican confraternity offered a space where typical Spanish patriarchy could be flipped. The confraternities offered women a place where they could adopt leadership positions and authority through positions of mayordomas and madres in the confraternity, often even holding founder's status.[49] Status as a member of a confraternity also gave black women a sense of respectability in the eyes of Spanish society. Going as far, in some cases, as to grant legal privileges when being examined and tried by the Inquisition.[50] They also took up the responsibility of providing basic medical services as nurses.[51] Women were often in charge of acquiring funding for the confraternity through limosnas (alms), a form of charity, because they were, evidently, better at it than the men. That being said, some Spanish heritage women that were wealthy decided to fund some of these confraternities directly.[51] This establishment of wealth also led to a shift in tendencies in female empowerment and involvement in confraternities in the 18th century. This shift was essentially a Hispanicization of the male members of the confraternity which may have involved an adoption of the Spanish system of patriarchy. This pattern, roughly in the 18th century, led to a policing of female members in order to better comply with Spanish gender norms.[52] The Hispanicization of the confraternities gradually led from a transfer in racial title from de negros, "of Blacks," to despues españoles, "later Spanish."[53] This is in large part due to the fact that "Socioeconomic factors had become more important than race in determining rank by the end of the eighteenth century".[54]

Religious institutions also owned black slaves, including the landed estates of the Jesuits[55] as well as urban convents and individual nuns.[56]

Economic activity

Important economic sectors such as sugar production and mining relied heavily on slave labor during that time.[15] After 1640, slave labor became less important but the reasons are not clear. The Spanish Crown cut off contacts with Portuguese slave traders after Portugal gained its independence. Slave labor declined in mining as the high profit margins allowed the recruitment of wage labor. In addition, the indigenous and mestizo population increased, and with them the size of the free labor force.[15] In the later colonial period, most slaves continued to work in sugar production but also in textile mills, which were the two sectors that needed a large, stable workforce. Neither could pay enough to attract free laborers to its arduous work. Slave labor remained important to textile production until the later 18th century when cheaper English textiles were imported.[15]

Although integral to certain sectors of the economy through the mid-18th century, the number of slaves and the prices they fetched fell during the colonial period. Slave prices were highest from 1580 to 1640 at about 400 pesos. It decreased to about 350 pesos around 1650, staying constant until falling to about 175 pesos for an adult male in 1750. In the latter 18th century, mill slaves were phased out and replaced by indigenous, often indebted, labor. Slaves were nearly non-existent in the late colonial census of 1792.[15] While banned shortly after the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence, the practice did not definitively end until 1829.[21]

Afro-Mexicans and race mixture

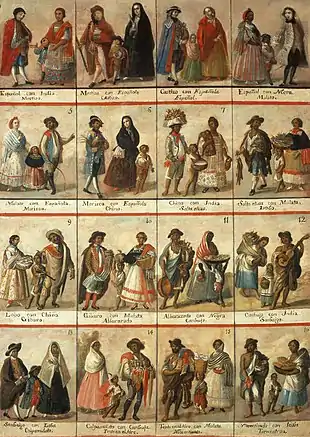

From early in the colonial period, African and African-descended people had offspring with Europeans or indigenous people. This led to an elaborate set of racial terms for mixtures which appeared during the 18th century. The offspring of mixed-race couples was divided into three general groups: Mestizo for (Spanish) White/indigenous, Mulatto for (Spanish) White/black and Lobo "wolf" or Zambo, sometimes used as a synonym; and Zambaigo for black/indigenous. However, there was overlap in these categories which recognized black mestizos. Black mestizos account for less than .5 percent of the Mexican population as of today. In addition, skin tone further divided the mestizo and mulatto categories. This loose hierarchical system of classification is sometimes called the sistema de castas, although its existence has recently been questioned as a 20th century ideological construct. Las castas paintings were produced during the 18th centuries, commissioned by the King of Spain to reflect Mexican society at that time. They portray the three races, European, indigenous and African and their complicated mixing. They are based on family groups, with parents and children labeled according to their caste. They have 16 squares in a hierarchy.

Some genetic tests show that an average Mexican has about 4% sub-Saharan African ancestry, indicating that the Afro-Mexican population "disappeared" because it was absorbed into the larger Mexican gene pool.[57] Other studies show that African admixture in modern day Mexicans largely reflects the African admixture already present in Spanish settlers.[4]

Gallery of Afro-Mexican casta paintings

Castas painting showing the various race combinations.

Castas painting showing the various race combinations. Español, Negra, Mulatta José Joaquín Magón.

Español, Negra, Mulatta José Joaquín Magón. From Español and Negra, Mulato. Anon. 18th c. Mexico.

From Español and Negra, Mulato. Anon. 18th c. Mexico. De Español y Mulata, Morisca. Anon. 18th c. Mexico.

De Español y Mulata, Morisca. Anon. 18th c. Mexico. Lobo y Mestiza, Cambujo. Anon. 18th c.

Lobo y Mestiza, Cambujo. Anon. 18th c. De Chino y Mulata, Alvarazada. Anon. 18th c.

De Chino y Mulata, Alvarazada. Anon. 18th c. De Mestizo y Albarazada, Barsina. Anon. 18th c.

De Mestizo y Albarazada, Barsina. Anon. 18th c..jpg.webp) From Mulata and Español, Morisca, Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz. 18th c. Mexico.

From Mulata and Español, Morisca, Juan Patricio Morlete Ruiz. 18th c. Mexico. "From male Spaniard and Mulatta: Morisca". Miguel Cabrera, 18th c. Mexico.

"From male Spaniard and Mulatta: Morisca". Miguel Cabrera, 18th c. Mexico. Las castas mexicanas. Ignacio Maria Barreda. 1777.

Las castas mexicanas. Ignacio Maria Barreda. 1777.

Afro-Mexicans and Mexican independence

The armed insurgency for independence broke out in September 1810 was led by the American Spanish secular priest Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. Hidalgo did not articulate a coherent program for independence, but in an early proclamation condemned slavery and the slave trade, and called for the abolition of tributes, which were paid by Indians, blacks, mulattoes and castas. He mandated in November 1810 that "slave masters must, whether Americans [New World-born] or Europeans, give [their slaves] liberty within ten days, on pain of death that their lack of observance of this article will apply to them."[58] Hidalgo was captured, defrocked, and executed in 1811, but his former seminary student, secular priest José María Morelos continued the insurgency for independence. He did articulate a program for independence in the Sentimientos de la Nación at the 1813 Congress of Chilpancingo that also called for the abolition of slavery, an institution which was already practically defunct. Point 15 is "That prohibit slavery forever, as the distinction of caste, being all equal and only vice and virtue distinguish an American from the other." Morelos like Hidalgo was captured and killed, but the struggle for independence continued in the "hot country" of southern Mexico under Vicente Guerrero, who is controversially portrayed as having African roots in modern Mexico. Royalist officer Agustín de Iturbide had fought the insurgents changed his allegiance, but now fought for independence. He gained the trust of Guerrero and the Plan de Iguala, named for the city in the hot country where it was proclaimed, laid out the aims of the insurgency, calling for independence, the primacy of Catholicism, and monarchy, with point 12 mandating "All inhabitants of the Empire, without any distinction other than merit and virtue, are citizens fit for whatever employment they choose." The alliance Guerrero and Iturbide led to the formation of the Army of the Three Guarantees. Spanish imperial rule collapsed, and Mexico gained its independence in September 1821. Despite political independence, abolition of slavery did not come about until Guerrero became President of Mexico in 1829.[59]

Conflict with the U.S. over the expansion of slavery

Although Mexico did not abolish slavery immediately after independence, the expansion of Anglo-American settlement in Texas with their black slaves became a point of contention between the U.S. and Mexico. The northern territory had been claimed by the Spanish Empire but not settled beyond a few missions. The Mexican government saw a solution to the problem of Indian attacks in the north by inviting immigration by U.S. Americans. Rather than settling in the territory contested by northern Indian groups, the Anglo-Americans and their black slaves established farming in eastern Texas, contiguous to U.S. territory in Louisiana. Mexican President Anastasio Bustamante, concerned that the U.S. would annex Texas, sought to limit Anglo-American immigration in 1830 and mandate no new slaves in the territory.[60][61] Texas slave-owner and settler Stephen F. Austin viewed slavery as absolutely necessary to the success of the settlement, and managed to get an exemption from the law. Texas rebelled against the central Mexican government of Antonio López de Santa Anna, gaining its de facto independence in 1836. The Texas Revolution meant the continuation of black slavery and when Texas was annexed to the U.S. in 1845, it entered the Union as a slave state. However, Mexico refused to acknowledge the independence of the territory until after the Mexican American War (1846-1848), and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo drew the border between the two countries. After the ignominious defeat by the U.S., Mexican President José Joaquín de Herrera sent a bill to congress to create the state of Guerrero, named after the mixed-race hero of independence, from parts of Michoacan, Puebla, and Mexico, in the hot country where the insurgent leader held territory. Mexico became a destination for some Black slaves and mixed-race Black Seminoles fleeing enslavement in the U.S. They were free once they crossed into Mexican territory. [62]

Demography

.jpg.webp)

According to the 2015 Encuesta Intercensal, there were 1,381,853 Mexicans that self-identified as Afro-descendants, or 1.2% of the country's population.[1] This is the first time that the government of Mexico has asked citizens whether they identify as Afro-Mexican. Places with large Afro-Mexican communities are: Costa Chica of Guerrero, Costa Chica of Oaxaca and Veracruz. While Northern Mexico has some towns with a minority of Mexicans of African descent. Afro-descendants can be found throughout the country, however they are numerically insignificant in some states. There are also recent immigrants of African and Caribbean origin.[8]

Afro-Mexican population in the Costa Chica

The Costa Chica ("small coast" in Spanish) extends from Acapulco to the town of Puerto Ángel in Oaxaca in Mexico's Pacific coast. The Costa Chica is not well known to travelers, with few attractions, especially where Afro-Mexicans live. Exceptions to this are the beaches of Marquelia and Punta Maldonado in Guerrero and the wildlife reserve in Chacahua, Oaxaca.[63] The area was very isolated from the rest of Mexico, which prompted runaway slaves to find refuge here. However, this has changed to a large extent with the building of Fed 200 which connects the area to Acapulco and other cities on the Pacific coast.[64] African identity and physical features are stronger here than elsewhere in Mexico as the slaves here did not intermarry to the extent that others did. Not only are black skin and African features more prominent, there are strong examples of African-based song, dance and other art forms.[65][66] Until recently, homes in the area were round mud and thatch huts, the construction of which can be traced back to what are now the Ghana and Ivory Coast.[63] Origin tales often center on slavery. Many relate to a shipwreck (often a slave ship) where the survivors settle here or that they are the descendants of slaves freed for fighting in the Mexican War of Independence.[17][67] The region has a distinct African-influenced dance called the Danza de los Diablos (Dance of the Devils) which is performed for Day of the Dead. They dance in the streets with wild costumes and masks accompanied by rhythmic music. It is considered to be a syncretism of Mexican Catholic tradition and West African ritual. Traditionally the dance is accompanied by a West African instrument called a bote, but it is dying out as the younger generations have not learned how to play it.[17][67]

There are a number of "pueblos negros" or black towns in the region such as Corralero and El Ciruelo in Oaxaca, and the largest being Cuajinicuilapa in Guerrero. The latter is home to a museum called the Museo de las Culturas Afromestizos which documents the history and culture of the region.[17][67]

The Afro-Mexicans here live among mestizos (indigenous/white) and various indigenous groups such as the Amuzgos, Mixtecs, Tlalpanecs and Chatinos .[63] Terms used to denote them vary. White and mestizos in the Costa Chica call them "morenos" (dark-skinned) and the indigenous call them "negros" (black). A survey done in the region determined that the Afro-Mexicans in this region themselves preferred the term "negro," although some prefer "moreno" and a number still use "mestizo."[21][17][68] Relations between Afro-Mexican and indigenous populations are strained as there is a long history of hostility.[63][64][69][70]

Afro-Mexican population in Veracruz

Like the Costa Chica, the state of Veracruz has a number of pueblos negros, notably the African named towns of Mandinga, Matamba, Mozambique and Mozomboa as well as Chacalapa, Coyolillo, Yanga and Tamiahua.[65][66][71] The town of Mandinga, about forty five minutes south of Veracruz city, is particularly known for the restaurants that line its main street.[66] Coyolillo hosts an annual Carnival with Afro-Caribbean dance and other African elements.[72]

However, tribal and family group were separated and dispersed to a greater extent around the sugar cane growing areas in Veracruz. This had the effect of intermarriage and the loss or absorption of most elements of African culture in a few generations.[66][73] This intermarriage means that while Veracruz remains "blackest" in Mexico's popular imagination, those with black skin are mistaken for those from the Caribbean and/or not "truly Mexican". The total population of people of African Descent including people with one or more black ancestors is 4 percent, the third highest of any Mexican state.[17]

The phenomena of runaways and slave rebellions began early in Veracruz with many escaping to the mountainous areas in the west of the state, near Orizaba and the Puebla border. Here groups of escaped slaves established defiant communities called "palenques" to resist Spanish authorities.[30][74] The most important Palenque was established in 1570 by Gaspar Yanga and stood against the Spanish for about forty years until the Spanish were forced to recognize it as a free community in 1609, with the name of San Lorenzo de los Negros. It was renamed Yanga in 1932.[30][75] Yanga was the first municipality of freed slaves in the Americas. However, the town proper has almost no people of obvious African heritage. Such people live in the smaller, more rural communities.[75]

Because African descendants dispersed widely into the general population, African and Afro-Cuban influence can be seen in Veracruz's music dance, improvised poetry, magical practices and especially food.[66][71][73] Veracruz son music, known as son jarocho and best known through the popularity of the hit "La Bamba" shows a mixture of Andalusian, Canary Islander and African influence.[76][30] Veracruz cooking commonly contains Spanish, indigenous and African ingredients and cooking techniques.[66] One defining African influence is the use of peanuts. Even though peanuts are native to the Americas, there is little evidence of their widespread use in the pre-Hispanic period. Peanuts were brought to Africa by the Europeans and the Africans adopted them, using them in stews, sauces and many other dishes. The slaves that came later would bring this new cooking with the legume to Mexico.[66] They can be found in regional dishes such as encacahuatado, an alcoholic drink called the torito, candies (especially in Tlacotalpan), salsa macha and even in mole poblano from the neighboring state of Puebla.[73] This influence can be seen as far west as Puebla, where peanuts are an ingredient in mole poblano.[66] Another important ingredient introduced by African cooking is the plantain, which came from Africa via the Canary Islands. In Veracruz, they are heavily used breads, empanadas, desserts, mole, barbacoa and much more. One other defining ingredient in Veracruz cooking is the use of starchy tropical roots, called viandas. They include cassava, malanga, taro and sweet potatoes.[66][73]

Afro-Mexican population in northern Mexico

Towns in north Mexico especially in Coahuila and along the country's border with Texas, also have Afro-Mexican populations and presence. Some enslaved and free Black Americans migrated into northern Mexico in the 19th century from the United States.[17] A few of the routes of the Underground Railroad led to Mexico.[77] One particular group was the Mascogos, a branch of Black Seminoles, originally from Florida, who escaped enslavement and free Black Americans intermingled with Seminole natives. Many of them settled in and around the town of El Nacimiento, Coahuila, where their descendants remain.[30]

Afro-Mexicans by state

| State | % Afro-Mexicans | Afro-Mexican population | % Partial Afro-Mexicans | % Total Afro-descendants | Total Afro-descendant population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mexico | 1.16% | 1,386,556 | 0.5% | 1.66% | 1,984,210 |

| Aguascalientes | 0.05% | 656 | 0.35% | 0.4% | 5,250 |

| Baja California | 0.22% | 7,294 | 0.31% | 0.53% | 17,573 |

| Baja California Sur | 1.55% | 11,036 | 0.72% | 2.27% | 16,163 |

| Campeche | 0.39% | 3,509 | 0.76% | 1.15% | 10,349 |

| Coahuila | 0.09% | 2,659 | 0.28% | 0.37% | 10,933 |

| Colima | 0.11% | 782 | 0.47% | 0.58% | 4,125 |

| Chiapas | 0.08% | 4,174 | 0.33% | 0.41% | 24,309 |

| Chihuahua | 0.08% | 2,845 | 0.25% | 0.33% | 11,734 |

| Durango | 0.01% | 175 | 0.64% | 0.65% | 11,405 |

| Guanajuato | 0.03% | 1,756 | 0.31% | 0.34% | 19,902 |

| Guerrero | 6.50% | 229,661 | 1.11% | 7.61% | 268,880 |

| Hidalgo | 0.07% | 2,000 | 0.54% | 0.61% | 17,435 |

| Jalisco | 0.78% | 61,189 | 0.35% | 1.13% | 88,646 |

| Estado de México | 1.88% | 304,327 | 0.45% | 2.33% | 377,171 |

| Mexico City | 1.80% | 160,535 | 0.53% | 2.33% | 207,804 |

| Michoacán | 0.08% | 3,667 | 0.51% | 0.59% | 27,048 |

| Morelos | 0.42% | 7,996 | 0.49% | 0.91% | 17,324 |

| Nayarit | 0.06% | 708 | 0.24% | 0.30% | 3,543 |

| Nuevo Leon | 1.49% | 76,280 | 0.36% | 1.85% | 94,710 |

| Oaxaca | 4.95% | 196,410 | 0.94% | 5.89% | 233,708 |

| Puebla | 0.12% | 7,402 | 0.47% | 0 .59% | 36,396 |

| Querétaro | 0.12% | 2,446 | 0.38% | 0.50% | 10,191 |

| Quintana Roo | 0.56% | 8,408 | 0.71% | 1.27% | 19,069 |

| San Luis Potosí | 0.04% | 1,087 | 0.51% | 0.55% | 14,948 |

| Sinaloa | 0.04% | 1,186 | 0.24% | 0.28% | 8,305 |

| Sonora | 0.06% | 1,710 | 0.30% | 0.36% | 10,261 |

| Tabasco | 0.11% | 2,634 | 0.92% | 1.03% | 24,671 |

| Tamaulipas | 0.29% | 9,980 | 0.36% | 0.65% | 22,371 |

| Tlaxcala | 0.06% | 763 | 0.44% | 0.50% | 6,364 |

| Veracruz | 3.28% | 266,090 | 0.79% | 4.07% | 330,178 |

| Yucatán | 0.12% | 2,516 | 0.89% | 1.01% | 21,181 |

| Zacatecas | 0.02% | 315 | 0.32% | 0.34% | 5,369 |

| Source: INEGI (2015)[78] | |||||

Notable Afro-Mexicans

The majority of Mexico's native Afro-descendants are Afromestizos, i.e. "mixed-race". Individuals of exclusively black ancestry make up a very low percentage of the total Mexican population, the majority being recent immigrants. The following list is of notable Afro-Mexicans, a noteworthy portion of which are the descendants of recent black immigrants to Mexico from Africa, the Caribbean and elsewhere in the Americas. Mexico employs jus soli when granting citizenship, meaning that any individual born on Mexican territory will be granted citizenship regardless of his or her parent's immigration status.

Colonial-era figures

- Juan Garrido (1487-1550) - Spanish black conquistador of Mexico of Congolese origin.

- Juan Valiente (1505-1553) - Spanish black conquistador and resident of Puebla.

- Juan Roque (died 1623) - Wealthy and prominent Afro-Mexican of New Spain known for his will and testament

- Gaspar Yanga (born 1545) - founder of the first free African township in the Americas, in 1609[79]

Politics

- Vicente Guerrero (1782-1831) - has been portrayed as Afromestizo although this is disputed. Mexican President and abolitionist[80]

- Joaquín Hendricks Díaz (born 1951) - former governor of Quintana Roo

- Fidel Herrera (born 1949) - former governor of Veracruz

- René Juárez Cisneros (born 1956) - former governor of Guerrero

- Pío Pico (1801-1894) - last Mexican governor of Alta California[81]

Entertainment

- Álvaro Carrillo - composer/songwriter[82]

- Jean Duverger - dancer, singer, and sportscaster of French-Haitian descent (Mexico-born)

- Abraham Laboriel, Sr. - musician of Honduran Garifuna origin; one of the most recorded bass guitarists in popular music

- Johnny Laboriel - rock and roll singer of Honduran Garifuna origin[83]

- Kalimba Marichal - Mexican singer and actor born to Afro-Cuban parents.

- Toña la Negra - singer of partial Haitian origin.[84]

- Lupita Nyong'o - Kenyan-Mexican actress (Mexico-born)

- Alejandra Robles - Singer and dancer from the Costa Chica of Oaxaca with Afro-Mexican descent via her paternal grandfather.

Visual arts

- Elizabeth Catlett - African-American artist (naturalized Mexican)

- Juan Correa - 18th-century Mexican painter who was the son of a dark-skinned (possibly Mulato) Spaniard from Cadiz and an Afro-Mexican woman.

- Julia López - painter from the Costa Chica of Guerrero

- Leonel Maciel - artist of mixed African, Asian and indigenous roots

Sports

- Alfredo Amézaga - baseball player

- Melvin Brown - Jamaican-Mexican footballer (Mexico-born)

- Tomás Campos - footballer

- Adrián Chávez - footballer (African-American father)

- François Endene - Cameroonian-Mexican footballer (naturalized Mexican)

- Omar Flores - footballer

- Edoardo Isella - Honduran-Mexican footballer (Mexico-born)

- El Hijo del Fantasma-wrestler

- Joao Maleck - Cameroonian-Mexican footballer (Mexico-born)

- Roberto Nurse - Panamanian-Mexican footballer (Mexico-born)

- Jorge Orta - baseball player

- Carlos Alberto Peña - footballer

- Marvin Piñón - footballer

- Johnny Rodz- wrestler (Mexican father)

- James de la Rosa - boxer

- Juan de la Rosa - boxer

- Giovani dos Santos - footballer (Afro-Brazilian father)*

- Jonathan dos Santos - footballer (Afro-Brazilian father)

Fictional figures

The comic character Memín Pinguín, whose magazine has been available in Latin America, the Philippines, and the United States newsstands for more than 60 years, is an Afro-Cuban. The Mexican government issued a series of five stamps in 2005 honoring the Memín comic-book series. The issue of these stamps was considered racist by some groups in the United States and praised by the Mexican audience who remember growing up with the magazine.

Gallery

Performance of the Danza de los Diablos, associated with the Afro-Mexican population of the Costa Chica.

Performance of the Danza de los Diablos, associated with the Afro-Mexican population of the Costa Chica.

.jpg.webp) An Afromestizo from the coast of Oaxaca holding a Pelota mixteca.

An Afromestizo from the coast of Oaxaca holding a Pelota mixteca. Girls in Punta Maldonado, Cuajinicuilapa, Guerrero.

Girls in Punta Maldonado, Cuajinicuilapa, Guerrero. Woman getting ready for the Carnival in Coyolillo, Actopan, Veracruz.

Woman getting ready for the Carnival in Coyolillo, Actopan, Veracruz.

See also

Further reading

- Aguirre Beltrán, Gonzalo, La población negra de México, 1519-1810: Estudio etnohistórico. Mexico 1946.

- Alberro, Solange, "Juan de Morga and Gertrudis de Escobar: Rebellious Slaves." In Struggle and Survival in Colonial America, eds. David G. Sweet and Gary B. Nash. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1981.

- Arce, B. Christine. Mexico's Nobodies: The Cultural Legacy of the Soldadera and Afro-Mexican Women. Albany: State University of New York Press 2016.

- Archer, Christon. "Pardos, Indians, and the Army of New Spain: Inter-relationships and Conflicts, 1780-1810." Journal of Latin American Studies 6:2(1974), 231-55.

- Bennett, Herman L. Africans in Colonial Mexico: Absolutism, Christianity, and Afro-Creole Consciousness, 1570-1640. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 2003.

- Bowser, Frederick. "The Free Person of Color in Mexico City and Lima," in Race and Slavery in the Western Hemisphere: Quantitative Studies, 331-368. Eds. Stanley Engerman and Eugene D. Genovese. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1975.

- Boyd-Bowman, Peter. "Negro Slaves in Colonial Mexico." The Americas 26(no.2) Oct. 1969), pp. 134-151.

- Bristol, Joan Cameron.Christians, Blasphemers, and Witches: Afro-Mexican Ritual Practice in the Seventeenth Century. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2007.

- Carroll, Patrick J. Blacks in Colonial Veracruz. Austin: University of Texas Press 1991.

- Cope, R. Douglas. The Limits of Racial Domination. Madison: University of Wisconsin Pree 1994.

- Davidson, David. "Negro Slave Control and Resistance in Colonial Mexico, 1519-1650". Hispanic American Historical Review 46(3) 1966, 237-43.

- Deans-Smith, Susan. "'Dishonor in the hands of Indians, Spaniards, and Blacks': The (racial) politics of painting in early modern Mexico." In Race and classification. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2009.

- Gerhard, Peter. "A Black Conquistador in Mexico." Hispanic American Historical Review 58:3(1978), 451-9.

- Gutiérrez Brockington, Lolita. The Leverage of Labor: Managing the Cortés Haciendas in Tehuantepec, 1588-1688. Durham: Duke University Press 1989.

- Konrad, Herman W. A Jesuit Hacienda in Colonial Mexico: Santa Lucía, 1576-1767. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1980. (a chapter devoted to black slaves).

- Lewis, Laura A. "Colonialism and its Contradictions: Indians, Blacks and Social Power in Sixteenth and Seventeenth-Century Mexico" Journal of Historical Sociology Volume 9, Issue 4, pages 410–431, December 1996

- Lewis, Laura A. "Blacks, Black Indians, Afromexicans: the Dynamics of Race, Nation, and Identity in a Mexican Moreno Community (Guerrero)". American Ethnologist vol. 27, no. 4. 2000, pp. 898-926.

- Love, Edgar L. "Marriage Patterns of Persons of African Descent in a Colonial Mexico City Parish," Hispanic American Historical Review 51:4(1971), 79-91.

- Martínez, María Elena. 2004. "The Black Blood of New Spain: Limpieza De Sangre, Racial Violence, and Gendered Power in Early Colonial Mexico". The William and Mary Quarterly 61 (3). Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture: 479–520. doi:10.2307/3491806.

- Palmer, Colin A. Slaves of the White God: Blacks in Mexico, 1570-1650. Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1976.

- Proctor, Frank T. III. Damned Notions of Liberty: Slavery, Culture, and Power in Colonial Mexico, 1640-1769. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2010.

- Restall, Matthew. "Black Conquistadors: Armed Africans in Early Spanish America." The Americas vol. 57: 2, Oct. 2000 pp. 171–205.

- Restall, Matthew, ed. Beyond Black and Red: African-native Relations in Colonial Latin America. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2005.

- Schwaller, Robert. Géneros de Gente in Early Colonial Mexico: Defining Racial Difference. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press 2016.

- Seed, Patricia. 1982. "Social Dimensions of Race: Mexico City, 1753". Hispanic American Historical Review 62 (4). Duke University Press: 569–606. doi:10.2307/2514568.

- Sierra Silva, Pablo Miguel. Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico: Puebla de los Angeles 1531-1706. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018.

- Super, John C. "Miguel Hernández: Master of Mule Trains," In Struggle and Survival in Colonial America, eds. David G. Sweet and Gary B. Nash. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press 1981.

- Taylor, William B., "The Foundation of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe de los Morenos de Amapa," The Americas, 26 (1970):439-446.

- Vaughn, Bobby and Ben Vinson III,eds. Afroméxico. El pulso de la población negra en México: Una historia recodada, olvidada y vuelta a recorder. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica 2004.

- Vinson, Ben III. Bearing Arms for His Majesty: The Free-Colored Militia in Colonial Mexico. Stanford: Stanford University Press 2001.

- Vinson, Ben III. Before Mestizaje: The Frontiers of Race and Caste in Colonial Mexico. New York: Cambridge University Press 2018.

- von Germeten, Nicole. Black Blood Brothers: Confraternities and Social Mobility for Afro Mexicans. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 2006.

References

- "Principales resultados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015 Estados Unidos Mexicanos" (PDF). INEGI. p. 77. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 December 2015. Retrieved 9 December 2015.

- Archibold, Randal C. (2014-10-25). "Negro? Prieto? Moreno? A Question of Identity for Black Mexicans". New York Times. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- "Afromexicanos, un rostro olvidado de México que pide ser reconocido". CNN México. Retrieved November 1, 2014.

- https://expansion.mx/actualidad/2009/06/04/genoma-destapa-diferencias-de-mexicanos

- Sluyter, Andrew (2012). Black Ranching Frontiers: African Cattle Herders of the Atlantic World, 1500-1900. Yale University Press. p. 240. ISBN 9780300179927. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- "Africa's Lost Tribe In Mexico". New African. January 10, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- "Página no encontrada" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-12-10.

- "Documento Informativo sobre Discriminación Racial en México" (PDF). CONAPRED. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-22. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- De Castro, Rafa Fernandez (December 15, 2015). "Mexico 'discovers' 1.4 million black Mexicans—they just had to ask". Fusion. Retrieved October 18, 2016.

- "El Fuerte de San Juan de Ulúa y Yanga, en Veracruz, son declarados Sitios de Memoria de la Esclavitud". Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Hostoria. 7 December 2017. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Ibidem, p.29

- Tatiana Mendez, 2009, Escuela de Trabajo Social UNAM.

- Ibidem., p.113

- Aguirre Beltrán, 1989 p.166

- Frank T. Proctor III. Afro-Mexican Slave Labor in the Obrajes de Paños of New Spain, Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (PDF) (Report). University of Western Ontario. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 21, 2018. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Vaughn, Bobby (January 1, 2006). "Blacks In Mexico - A Brief Overview". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Ariane Tulloch. Afro-Mexicans: A short study on Identity (PDF) (MA). University of Kansas. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- "Reports for Caribbean and Latin American Customers". 23andMe Blog. 15 May 2019. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex, Book XII. Charles Dibble and Arthur J.O. Anderson, translators. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press 1975:19, 21.

- Gerhard, Peter. "A Black Conquistador in Mexico," Hispanic American Historical Review 58:3 (1978)

- Lovell Banks, Taunya (2005). "Mestizaje and the Mexican mestizo self: No hay sangre negra, so there is no blackness". Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal. 15 (199). Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Toribio de Benavente Motolinia. History of the Indians of New Spain. Translated by Elizabeth Andros Foster. Westport: Greenwood Press 1973:40-41.

- Yucatan Before and After the Conquest by Friar Diego de Landa. Translated by William Gates Dover Publications 1978, pp. 158, 159.

- Sierra Silva, Urban slavery, pp.27-28.

- Codex Telleriano-Remensis, translated and edited by Eloise Quiñones Keber. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1992:275.

- Sierra Silva, Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico, p.42-44.

- Sierra Silva, Urban Slavery, pp. 30-31.

- Clemence, Stella Risley, "Deed of Emancipation of a Negro Woman Slave, dated Mexico, September 14, 1585," Hispanic American Historical Review (10) 1930 pp.55-57.

- Bennett, Herman L. Colonial Blackness: A History of Afro-Mexico. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 2009

- Gonzales, Patrisia; Roberto Rodríguez (January 1, 1996). "African Roots Stretch Deep Into Mexico". Mexconnect. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Bennett, Herman L. (2009). Colonial Blackness: A History of Afro-Mexico. Indiana University Press. p. 11. ISBN 9780253223319.

- Bennet 2009, p. 18-19.

- Bennet 2009, p. 23.

- Bennet 2009, p. 26.

- Bennet 2009, p. 32-36.

- Bennet 2009, p. 15.

- Sierra Silva, Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico, pp. 40-42

- Lucena Salmoral, Manuel. Regulación de la esclavitud negra en las colonias de América española (1503-1886): Documentos para su estudio (Alcalá: University of Alcalá de Henares, 2005), pp. 52-53

- Tannenbaum, Frank. Slave and Citizen: The Negro in the Americas. New York: Vintage 1946

- Bennett, Herman L. Africans in Colonial Mexico: Absolutism, Christianity, and Afro-Creole Consciousness, 1570-1640. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 2003.

- Bennett, Herman L. and Andrew B. Fisher, "Africans in Colonial Mexico: Absolutism, Christianity, and Afro-Creole Consciousness". African Diaspora Archeology Newsletter, vol. 8, no. 5, article 13.

- Luna García, Sandra Nancy. "Espacios de convivencia y conflicto. Las cofradías de la población de origen africano en Ciudad de México, siglo XVII". Trashumante. Revista Americana de Historia Social (in Spanish). pp. 032–052. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- Von Germeten, Nicole (2006). Black Blood Brothers: Confraternities and Social Mobility for Afro Mexicans. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida. p. 14.

- Von Germeten. Black Blood Brothers. p. 12.

- Von Germeten. Black Blood Brothers. pp. 16–17.

- Von Germeten. Black Blood Brothers. p. 20.

- Von Germeten, Nicole. "Black Brotherhoods and Sisterhoods: Participatory Christianity in New Spain's Mining Towns". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Von Germeten. Black Blood Brothers. p. 20.

- Von Germeten. Black Blood Brothers. pp. 41–43.

- Von Germeten. Black Blood Brothers. p. 42.

- Von Germeten. Black Blood Brothers. p. 43.

- Von Germeten. "Black Brotherhoods and Sisterhoods: Participatory Christianity in New Spain's Mining Towns". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Von Germeten. "Black Brotherhoods and Sisterhoods: Participatory Christianity in New Spain's Mining Towns". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Von Germeten. Black Blood Brothers. p. 125.

- Konrad, Herman W. A Jesuit Hacienda in Colonial Mexico: Santa Lucía, 1576–1767. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1980.

- Sierra Silva, Urban Slavery in Colonial Mexico, pp. 76-106.

- "Your Regional Ancestry: Reference Populations".

- Tena Ramírez, Felipe. Leyes Fundamentals de México 1808-1957. Mexico: Editorial Porrúa 1957:21-22.

- Vincent, Theodore G. The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Mexico's First Black Indian President. University of Florida Press 2001.

- Menchaca, Martha. Recovering History, Constructing Race: The Indian, Black, and White Roots of Mexican Americans. Austin: University of Texas Press 2001.

- Henderson, Timothy J. A glorious defeat: Mexico and its war with the United States. New York: Macmillan 2007.

- Cornell, Sarah E. "Citizens of Nowhere: Fugitive Slaves and Free African Americans in Mexico, 1833–1857." Journal of American History, Volume 100, Issue 2, September 2013, Pages 351–374, https://doi.org/10.1093/jahist/jat253

- Vaughn, Bobby (September 1, 1998). "Mexico's Black heritage: the Costa Chica of Guerrero and Oaxaca". Mexconnect newsletter. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Jo Tuckman (July 6, 2005). "Mexico's forgotten race steps into spotlight". The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- "Relations between Hispanic and African Americans in the U.S. today seen through the prism of the "Memin Pinguin" Controversy". American Studies Today Online. Liverpool: American Studies Resources Centre John Moores University. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Hursh Graber, Karen (September 1, 2008). "Immigrant Cooking in Mexico: The Afromestizos of Veracruz". Mexconnect magazine. ISSN 1028-9089. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- "Mexico's Dance of the Devils". The World. November 19, 2010. Archived from the original on April 23, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Rodríguez, Nemesio J. "De afromestizo a pueblos negro: hacia la construcción de un sujeto sociopolítico en la Costa Chica" [From Afromestizo to pueblos negros: towards a construction of a sociopolitcal subject in the Costa Chica] (in Spanish). Mexico City: UNAM. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Khaaliq, Hakeem (July 14, 2014). "¿Quiénes son los afro-mexicanos?" [Who are the Black Mexicans?] (in Spanish). Univision. Retrieved July 15, 2014.

- Muhammad Ali, Queen (April 19, 2014). "Invisible Mexico Exhibit by Nation19 Magazine / APDTA". Nation19 Magazine.

- "Afromestizaje prevalece en Veracruz" [Afromestizaje prevails in Veracruz]. Radio y Television Veracruz (in Spanish). Veracruz. October 7, 2011. Archived from the original on December 20, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- "En Coyolillo, Carnaval de cultura y tradición afromestiza" [In Coyolillo, Carnival of Afromestiza culture and tradition]. Diario AZ (in Spanish). Veracruz. February 22, 2012. Archived from the original on February 19, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- Zarela Martínez (September 12, 2001). "The African Face of Veracruz". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- "The African Presence in México: From Yanga to the Present". Oakland Museum of California. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012. Retrieved April 26, 2012.

- Alexis Okeowo (September 15, 2009). "Blacks in Mexico: A Forgotten Minority". Time. Retrieved April 27, 2012.

- https://sites.google.com/site/muremex/son-jarocho

- "Aboard the Underground Railroad". National Park Service. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Tabulados de la Encuesta Intercensal 2015". INEGI. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. ed. Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion. Greenwood Press: Westport, Connecticut. 2007.

- Vincent, Theodore G (2001). The Legacy of Vicente Guerrero, Mexico's First Black Indian President. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-2422-6.

- "'Black Angelenos': Pride and Prejudice". Daily News of Los Angeles. July 31, 1988. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2011-03-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) | accessdate=March 9, 2011

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-12-18. Retrieved 2011-02-06.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "African Presence in the Americas". Oakland Tribune, The. February 18, 2010. Retrieved October 20, 2010.

External links

- Afromexicanos from Oaxaca Población Siglo XXI, a magazine published by the Government of Oaxaca

- Afrodescendientes en México, una historia de silencio y discriminación from CONAPRED

- Black Mexico: Nineteenth-Century Discourses of Race and Nation (Dissertation for Ph.D. in History from Brown University)

- From Curing to Witchcraft: Afro-Mexicans and the Mediation of Authority at Project MUSE

- Afro-Mexico: Dancing between Myth and Reality at Project MUSE

- Genetic relationship of a Mexican Afromestizo population through the analysis of the 3' haplotype of the beta globin gene in betaA chromosomes

- Black Seminole Indians from the Handbook of Texas Online (includes information on the mascogos of Mexico)