Miao Rebellion (1795–1806)

The Miao Rebellion of 1795–1806 was an anti-Qing uprising in Hunan and Guizhou provinces, during the reign of the Jiaqing Emperor. It was catalyzed by tensions between local populations and Han Chinese immigrants. Bloodily suppressed, it served as the antecedent to the much larger uprising of Miao Rebellion (1854–73).

| Miao Rebellion 1795–1806 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Miao Rebellions | |||||||

Battle of Lancaoping (1795) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Qing dynasty | Miao | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Shi Sanbao Shi Liudeng | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| at least 20 000 soldiers | |||||||

The term "Miao", as the anthropologist Norma Diamond explains, does not mean only the antecedents of today's Miao national minority; it is a term, which had been used by the Chinese to describe various indigenous, mountain tribes of Guizhou and other south-western provinces of China, which shared similar cultural traits.[1] They consisted of 40–60% population of the province.[2]

Background and causes

The Qing Dynasty used tyranny rather than forced assimilation towards their non-Chinese inhabitants. In the south-west, since 15th century, in provinces of Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi and Sichuan, the most common way of rule was through semi-independent local chieftains, called tusi, on whom the emperor bestowed titles, demanding only taxes and peace in their territories.[1]

However, Han Chinese immigration was forcing the original inhabitants out of the best lands; Guizhou's territory, although sparsely populated, consists mainly of high mountains, which offer little arable land.[3] The Chinese state "followed" the immigrants, establishing its structures, first military, then civil, and displacing semi-independent tusi with regular administration over time. This practice, called gaitu guiliu, led to conflicts.[1][4]

The uprising was one of the long series dating back to Ming dynasty's conquest of the area. Whenever tensions reached a critical point, the people rose in revolt. Each rebellion, bloodily put down, left simmering hatred, and problems which were rather suppressed than solved. Basic questions of misrule, official abuse, extortion, over-taxation and land-grab remained. Mass Chinese immigration put a strain on scarce resources, but officials preyed on rather than administered the population. The quality of the officialdom in Guizhou and neighbouring areas remained very low.[4] Great uprisings took place in Ming times, and during Qing dynasty in 1735–36, 1796–1806, and last and the largest in 1854-1873.

The uprising and its aftermath

The previous rebellion of 1736 had been met with harsh measures, with the effect of the second half of the 18th century being relatively calm, i.e. the numerous local incidents were not enough to challenge governmental authority. However, the officials were unnerved by heterodox sects spreading their teachings among both Han and Miao. In 1795 the tensions reached the point of explosion and the Miaos, led by Shi Liudeng and Shi Sanbao, rose again.[2]

Hunan was the main area of fighting, with some taking place in Guizhou. The Qing dynasty sent banner troops, Green Standard battalions and mobilized local militias and self-defence units. The lands of rebellious Miao were confiscated, to punish them and to increase the power of state; this action, however, provoked further conflicts, because new Han landowners ruthlessly exploited their Miao tenants. On the pacified territories forts and military colonies were set up, and Miao and Chinese territories were separated by the wall with watchtowers. Still, it took eleven years to finally quell the rebellion.[2] Relocating Green Standard troops from Hubei to Hunan in 1795, to deal with the Miao, facilitated the White Lotus Rebellion, because of the diminished control in the northern province.[5]

Military action was followed by the policy of forced assimilation: traditional dress was forbidden and an ethnic segregation policy enforced. Nevertheless, the deep causes of unrest remained unchanged and the tensions grew again, until in 1854 they exploded in the largest of Miao uprisings. Relatively few of Hunan Miao, "pacified" in 1795–1806, participated in the rebellions of the 1850s.[6]

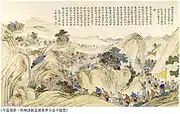

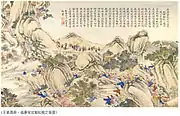

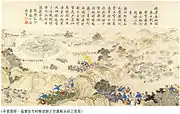

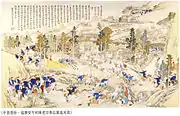

Gallery

Notes

- Norma Diamond (1995). "Defining the Miao: Ming, Qing, and Contemporary Views". In Stevan Harrell (ed.). Cultural Encounters on China's Ethnic Frontiers. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0-295-97528-8.

- Elleman, Bruce A. (2001). "The Miao Revolt (1795–1806)". Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795-1989. London: Routledge. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-415-21474-2.

- Robert D. Jenks (1994). Insurgency and Social Disorder in Guizhou: The "Miao" Rebellion, 1854-1873. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 19–20, 25. ISBN 0-8248-1589-0.

Guizhou had an overall population density ... rather low ... Han encroachment on Miao land was considered to be a serious problem by almost all officials in the nineteenth century ... [Immigrants] intensified the competition for land, which was already scarce ... poor soil and mountainous terrain.

- John K. Fairbank; Denis Twitchett (1978). The Cambridge History of China. Late Ch'ing 1800–1911, Part 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 132–133. ISBN 978-0-521-21447-6.

- Kuhn, Philip A. (1980). Rebellion and Its Enemies in Late Imperial China. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. pp. 53. ISBN 0-674-74954-5.

- Robert D. Jenks (1994). Insurgency and Social Disorder in Guizhou: The "Miao" Rebellion, 1854-1873. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. p. 67. ISBN 0-8248-1589-0.

Once again the measures taken against the Miao were draconian, but they were applied largely in western Hunan rather than in Guizhou. They included forced assimilation (e.g., the Miao were ordered to wear Chinese dress instead of tribal dress), ... and the construction of a long wall with manned watchtowers to insure that Miao and Han remained segregated ... it did achieve results in western Hunan, for very few of the Miao there participated in the rebellions of the Xianfeng-Tongzhi period.