Mongolia under Qing rule

Mongolia under Qing rule was the rule of the Qing dynasty over the Mongolian steppe, including the Outer Mongolian 4 aimags and Inner Mongolian 6 leagues from the 17th century to the end of the dynasty. "Mongolia" here is understood in the broader historical sense (see Greater Mongolia and Mongolian Plateau). The last Mongol Khagan Ligden saw much of his power weakened in his quarrels with the Mongol tribes, was defeated by the Later Jin dynasty, and died soon afterwards. His son Ejei Khan gave Hong Taiji the imperial authority, ending the rule of Northern Yuan dynasty then centered in Inner Mongolia by 1635. However, the Khalkha Mongols in Outer Mongolia continued to rule until they were overrun by the Dzungar Khanate in 1690, and they submitted to the Qing dynasty in 1691.

| Mongolia under Qing rule | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regions of the Qing dynasty | |||||||||||||||

| 1635–1911 | |||||||||||||||

Imperial Seal

| |||||||||||||||

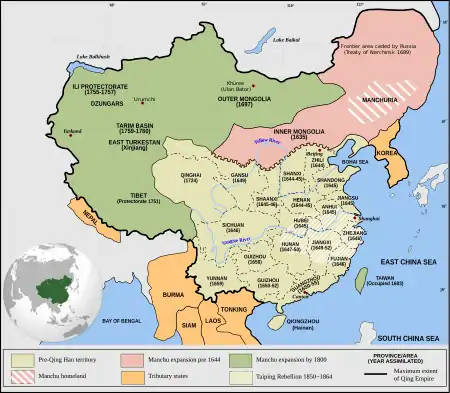

Outer Mongolia and Inner Mongolia within the Qing Empire, c. 1820. | |||||||||||||||

| Anthem | |||||||||||||||

| National anthem: 《普天樂》 "pǔ tiān yuè" (English: "Pu Tian Yue") (1878–1896) Royal anthem: 《李中堂乐》 "lǐ zhōng táng yuè" (English: "Tune of Li Zhongtang") (1896–1906) 《颂龙旗》 "Sòng lóng qí" (English: "Praise the Dragon Flag") (1906–1911) 《鞏金甌》 "Gong Jin'ou" (English: "Cup of Solid Gold") (1911) | |||||||||||||||

| Capital | Uliastai (Outer Mongolia)[note 1] Hohhot (Inner Mongolia) | ||||||||||||||

| • Type | Qing hierarchy | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Khalkha jirum | ||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||

| 1635 | |||||||||||||||

• The surrender of the northern Khalkha. | 1691 | ||||||||||||||

• Outer Mongolia declares its independence from the Qing dynasty | December 1911 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| History of Mongolia |

|---|

The Manchu-led Qing dynasty had ruled Inner and Outer Mongolia for over 200 years. During this period Qing rulers established separate administrative structures to govern each region. While the empire maintained firm control in both Inner and Outer Mongolia, the Mongols in Outer Mongolia (which is further from the capital Beijing) enjoyed more degree of autonomy,[1] and also retained their own language and culture during this period.[2]

History

The Khorchin Mongols allied with Nurhaci and the Jurchens in 1626, submitting to his rule for protection against the Khalkha Mongols and Chahar Mongols. 7 Khorchin nobles died at the hands of Khalkha and Chahars in 1625. This started the Khorchin alliance with the Qing.[3]

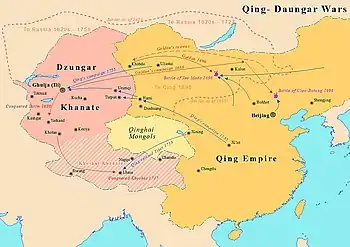

During the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, most regions inhabited by ethnic Mongols, notably Outer and Inner Mongolia became part of the Qing Empire. Even before the dynasty began to take control of China proper in 1644, the escapades of Ligden Khan had driven a number of Mongol tribes to ally with the Later Jin. The Later Jin conquered a Mongol tribe in the process of war against the Ming. Nurhaci's early relations with the Mongols tribes was mainly an alliance.[4][5] After Ligden's defeat and death his son had to submit to the Later Jin, and when the Qing dynasty was founded the following year, most of what is now called Inner Mongolia already belonged to the new state. The Khalkha Mongols in Outer Mongolia joined in 1691 when their defeat by the Dzungars left them without a chance to remain independent. The Khoshud in Qinghai were conquered in 1723/24. The Dzungars were finally destroyed, and their territory conquered, in 1756/57 during the Dzungar genocide. The last Mongols to join the empire were the returning Torgud Kalmyks at the Ili in 1771.

After conquering the Ming, the Qing identified their state as Zhongguo (中國, the term for "China" in modern Chinese), and referred to it as "Dulimbai Gurun" in the Manchu language. When the Qing conquered Dzungaria in 1759, they proclaimed that the new land which formerly belonged to the Dzungar Mongols was now absorbed into "China" (Dulimbai Gurun) in a Manchu language memorial.[6][7][8] The Qing expounded on their ideology that they were bringing together the "outer" non-Han Chinese like the Inner Mongols, Eastern Mongols, Oirat Mongols, and Tibetans together with the "inner" Han Chinese, into "one family" united in the Qing state.[9] The Manchu language version of the Convention of Kyakhta (1768), a treaty with the Russian Empire concerning criminal jurisdiction over bandits, referred to people from the Qing as "people from the Central Kingdom (Dulimbai Gurun)",[10][11][12][13] and the usage of "Chinese" (Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) in the convention certainly referred to the Mongols.[14] In the Manchu official Tulisen's Manchu language account of his meeting with the Torghut Mongol leader Ayuki Khan, it was mentioned that the Torghut Mongols were unlike the Russians but were instead like the "people of the Central Kingdom" (中國之人; Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) such as the Manchus.[15] Nevertheless, due to the different ways of legitimization for different peoples in the Qing Empire, some non-Han people such as the Mongols considered themselves as subjects of the Qing state but outside China or Khitad.

From the early years, the Manchus' relations with the neighboring Mongol tribes had been crucial in the dynasty development. Nurhaci had exchanged wives and concubines with the Khalkha Mongols since 1594, and also received titles from them in the early 17th century. He also consolidated his relationship with portions of the Khorchin and Kharachin populations of eastern Mongols. They recognized Nurhaci as Khan, and in return leading lineages of those groups were titled by Nurhaci and married with his extended family. Nurhaci chose to variously emphasize either differences or similarities in lifestyles with the Mongols for political reasons.[16] Nurhaci said to the Mongols that "The languages of the Chinese and Koreans are different, but their clothing and way of life is the same. It is the same with us Manchus (Jušen) and Mongols. Our languages are different, but our clothing and way of life is the same." Later Nurhaci indicated that the bond with the Mongols was not based in any real shared culture, rather it was for pragmatic reasons of "mutual opportunism", when he said to the Mongols: "You Mongols raise livestock, eat meat and wear pelts. My people till the fields and live on grain. We two are not one country and we have different languages."[17] As Nurhaci formally declared independence from the Ming dynasty and proclaimed the Later Jin in 1616, he gave himself a Mongolian-style title, consolidating his claim to the Mongolian traditions of leadership. The banners and other Manchu institutions are examples of productive hybridity, combining "pure" Mongolian elements (such as the script) and Han Chinese elements. Intermarriage with Mongolian noble families had significantly cemented the alliance between the two peoples. Hong Taiji further expanded the marriage alliance policy; he used the marriage ties to draw in more of the twenty-one Inner Mongolian tribes that joined the alliance with the Manchus. Despite the growing intimacy of Manchu-Mongol ties, Ligdan Khan, the last Khan from the Chakhar, resolutely opposed the growing Manchu power and viewed himself as the legitimate representative of the Mongolian imperial tradition. But after his repeated losses in battle to the Manchus in the 1620s and early 1630s, as well as his own death in 1634, his son Ejei Khan eventually submitted to Hong Taiji in 1635 and the Yuan seal is also said to be handed in to latter, ending the Northern Yuan. Ejei Khan was given the title of Prince (Qin Wang, 親王). The surrendered Inner Mongols were divided into separate administrative banners. Soon afterwards the Manchus founded the Qing dynasty and became the ruler of China proper.

Ejei Khan died in 1661 and was succeeded by his brother Abunai. After Abunai showed disaffection with Manchu Qing rule, he was placed under house arrested in 1669 in Shenyang and the Kangxi Emperor gave his title to his son Borni. Abunai then bid his time and then he and his brother Lubuzung revolted against the Qing in 1675 during the Revolt of the Three Feudatories, with 3,000 Chahar Mongol followers joining in on the revolt. The Qing then crushed the rebels in a battle on April 20, 1675, killing Abunai and all his followers. Their title was abolished, all Chahar Mongol royal males were executed even if they were born to Manchu Qing princesses, and all Chahar Mongol royal females were sold into slavery except the Manchu Qing princesses. The Chahar Mongols were then put under the direct control of the Qing Emperor unlike the other Inner Mongol leagues which maintained their autonomy.

The Khalkha Mongols were more reluctant to come under Qing rule, only submitting to the Kangxi Emperor after they came under an invasion from the Oirat Mongol Dzungar Khanate under its leader Galdan.

The three khans of Khalkha in Outer Mongolia had established close ties with the Qing dynasty since the reign of Hong Taiji, but had remained effectively self-governing. While Qing rulers had attempted to achieve control over this region, the Oyirods to the west of Khalkha under the leadership of Galdan were also actively making such attempts. After the end of the war against the Three Feudatories, the Kangxi Emperor was able to turn his attentions to this problem and tried diplomatic negotiations. But Galdan ended up with attacking the Khalkha lands, and Kangxi's responded by personally leading Eight Banner contingents with heavy guns into the field against Galdan's forces, eventually defeating the latter. In the meantime Kangxi organized a congress of the rulers of Khalkha and Inner Mongolia in Duolun in 1691, at which the Khalkha khans formally declared allegiance to him. The war against Galdan essentially brought the Khalkhas to the empire, and the three khans of the Khalkha were formally inducted into the inner circles of the Qing aristocracy by 1694. Thus, by the end of the 17th century the Qing dynasty had put both Inner and Outer Mongolia under its control.

The Oirat Khoshut Upper Mongols in Qinghai rebelled against the Qing during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor but were crushed and defeated.

Khalkha Mongol rebels under Prince Chingünjav had plotted with the Dzungar leader Amursana and led a rebellion against the Qing at the same time as the Dzungars. The Qing crushed the rebellion and executed Chingünjav and his entire family.

Mongols were forbidden by the Qing from crossing the borders of their banners, even into other Mongol Banners and from crossing into neidi (the Han Chinese 18 provinces) and were given serious punishments if they did in order to keep the Mongols divided against each other to benefit the Qing.[18] Mongol pilgrims wanting to leave their banner's borders for religious reasons such as pilgrimage had to apply for passports to give them permission.[19]

Despite officially prohibiting Han Chinese settlement on the Manchu and Mongol lands, by the 18th century the Qing decided to settle Han refugees from northern China who were suffering from famine, floods, and drought into Manchuria and Inner Mongolia so that Han Chinese farmed 500,000 hectares in Manchuria and tens of thousands of hectares in Inner Mongolia by the 1780s.[20]

The Banner organization was implemented among the Inner Mongols and the title of Jasagh was granted to the leader of the banners to weaken autonomy.[21] The Banners replaced the tribal and clan structure and had the effect of dividing the Mongols, Mongol Princes used Chinese architecture to build their palaces.[22] Mongol nobles and the Qing sold to Han Chinese farmers Horqin's grasslands.[23] The Princes were controlled by the Qing, Han merchants lending caused Mongols to go into debt and monasteries were filling with Mongol males which occurred alongside a shrinking Mongol population. Han farmers leased Mongol Banner lands after the lands were taken as remittance for the debt of Mongol Princes' by Han merchants, the Qing government was petitioned by the Mongol Jasak prince of eastern Inner Mongolia's Ghorlos's Front Banner to legalize the Han settlers in the area in 1791.[24]

A group of Han Chinese during the Qing dynasty called "Mongol followers" immigrated to Inner Mongolia who worked as servants for Mongols and Mongol princes and married Mongol women. Their descendants continued to marry Mongol women and changed their ethnicity to Mongol as they assimilated into the Mongol people, an example of this were the ancestors of Li Shouxin. They distinguished themselves apart from "true Mongols" 真蒙古.[25][26][27]

In addition to sending Han exiles convicted of crimes to Xinjiang to be slaves of Banner garrisons there, the Qing also practiced reverse exile, exiling Inner Asian (Mongol, Russian and Muslim criminals from Mongolia and Inner Asia) to China proper where they would serve as slaves in Han Banner garrisons in Guangzhou. Russian, Oirats and Muslims (Oros. Ulet. Hoise jergi weilengge niyalma) such as Yakov and Dmitri were exiled to the Han banner garrison in Guangzhou.[28] In the 1780s after the Muslim rebellion in Gansu started by Zhang Wenqing 張文慶 was defeated, Muslims like Ma Jinlu 馬進祿 were exiled to the Han Banner garrison in Guangzhou to become slaves to Han Banner officers.[29] The Qing code regulating Mongols in Mongolia sentenced Mongol criminals to exile and to become slaves to Han bannermen in Han Banner garrisons in China proper.[30]

Inner Mongols and Khalkha Mongols rarely knew their ancestors past 4 generations and Mongol tribal society was not organized among patrilineal clans contrary to what was commonly though, but included unrelated people at the base unit of organization.[31] The Qing tried but failed to promote the Chinese Neo-Confucian ideology of organizing society along patrimonial clans among the Mongols.[32]

Governance

For the administration of Mongol regions, a bureau of Mongol affairs was founded, called Monggol jurgan in Manchu. By 1638 it had been renamed to Lifan Yuan, though it is sometimes translated in English as the "Court of Colonial Affairs" or the "Board for the Administration of Outlying Regions". This office reported to the Qing emperor and would eventually be responsible not only for the administration of Inner and Outer Mongolia, but also oversaw the appointments of Ambans in Tibet and Xinjiang, as well as Qing relations with Russia. Apart from day-to-day work, the office also edited its own statutes and a code of law for Outer Mongolia.

Unlike Tibet, Mongolia during the Qing period did not have any overall indigenous government. In Inner Mongolia, the empire maintained its presence through the Qing military forces based along Mongolia's southern and eastern frontiers, and the region was under tight control. In Outer Mongolia, the entire territory was technically under the jurisdiction of the military governor of Uliastai, a post only held by Qing bannermen, although in practice by the beginning of the 19th century the Amban at Urga had general supervision over the eastern part of the region, the tribal domains or aimags of the Tushiyetu Khan and Sechen Khan, in contrast to the domains of the Sayin Noyan Khan and Jasaghtu Khan located in the west, under the supervision of the governor at Uliastai. While the military governor of Uliastai originally had direct jurisdiction over the region around Kobdo in westernmost Outer Mongolia, the region later became an independent administrative post. The Qing government administered both Inner and Outer Mongolia in accordance with the Collected Statutes of the Qing dynasty (Da Qing Hui Dian) and their precedents. Only in internal disputes the Outer Mongols or the Khalkhas were permitted to settle their differences in accordance with the traditional Khalkha Code. To the Manchus, the Mongol link was martial and military. Originally as "privileged subjects", the Mongols were obligated to assist the Qing court in conquest and suppression of rebellion throughout the empire. Indeed, during much of the dynasty the Qing military power structure drew heavily on Mongol forces to police and expand the empire.

The Mongolian society consisted essentially of two classes, the nobles and the commoners. Every member of the Mongolian nobility held a rank in the Qing aristocracy, and there were ten ranks in total, while only the banner princes ruled with temporal power. In acknowledgement of their subordination to the Qing dynasty, the banner princes annually presented tributes consisting of specified items to the Emperor. In return, they would receive imperial gifts intended to be at least equal in value to the tribute, and thus the Qing court did not consider the presentation of tribute to be an economic burden to the tributaries. The Mongolian commoners, on the other hand, were for the most part banner subjects who owed tax and service obligations to their banner princes as well as the Qing government. The banner subjects each belonged to a given banner, which they could not legally leave without the permission of the banner princes, who assigned pasturage rights to his subjects as he saw fit, in proportion to the number of adult males rather than in proportion to the amount of livestock that to graze.

By the end of the eighteenth century, Mongolian nomadism had significantly decayed. The old days of nomad power and independence were gone. Apart from China's industrial and technical advantage over the steppe, three main factors combined to reinforce the decline of the Mongol's once-glorious military power and the decay of the nomadic economy. The first was the administrative unit of the banners, which the Qing rulers employed to divide the Mongols and sever their traditional lines of tribal authority; no prince could expand and acquire predominant power, and each of the separate banners was directly responsible to the Qing administration. If a banner prince made trouble, the Qing government had the power to dismiss him immediately without worrying about his lineage. The second important factor in the taming of the once powerful Mongols was the "Yellow Hat" school of the Tibetan Buddhism. The monasteries and lamas under the authority of the reincarnating lama resident in the capital Beijing were exempt from taxes and services and enjoyed many privileges. The Qing government wanted to tie the Mongols to the empire and it was Qing policy to fuse Tibetan Buddhism with Chinese religious ideas insofar as Mongolian sentiment would allow. For example, the Chinese god of war, the Guandi, was now equated with a figure which had long been identified with the Tibetan and Mongolian folk hero Geser Khan. While the Mongolian population was shrinking, the number of monasteries was growing. In both Inner and Outer Mongolia, about half of the male population became monks, which was even higher than Tibet where only about one third of male population were monks. The third factor in Mongolia's social and economic decline was an outgrowth of the previous factor. The building of monasteries had open Mongolia to the penetration of Chinese trade. Previously Mongolia had little internal trade other than non-market exchanges on a relatively limited scale, and there was no Mongolian merchant class. The monasteries greatly aided the Han Chinese merchants to establish their commercial control throughout Mongolia and provided them with direct access to the steppe. While the Han merchants frequently provoked the anger of the monasteries and the laity for several reasons, the net effect of the monasteries' role was support for Chinese trade. Nevertheless, the empire did make various attempts to restrict the activities of these Han merchants such as the implementation of annual licensing, because it had been the Qing policy to keep the Mongols as a military reservoir, and it was considered that the Han Chinese trade penetration would undermine this objective, although in many cases such attempts had little effects.

The first half of the 19th century saw the heyday of the Qing order. Both Inner and Outer Mongolia continued to supply the Qing armies with cavalry, although the government had tried to keep the Outer Mongols apart from the empire's wars in that century. Since the dynasty placed the Mongols well under its control, the government no longer feared of them. At the same time, as the ruling Manchus had become increasingly sinicized and population pressure in China proper emerged, the dynasty began to abandon its earlier attempts to block Han Chinese trade penetration and settlement in the steppe. After all, Han Chinese economic penetration served the dynasty's interests, because it not only provided support of the government's Mongolian administrative apparatus, but also bound the Mongols more tightly to the rest of empire. The Qing administrators, increasing in league with Han Chinese trading firms, solidly supported Chinese commerce. There was little that ordinary Mongols, who remained in the banners and continued their lives as herdsmen, could do to protect themselves against the growing exactions that banner princes, monasteries, and Han creditors imposed upon them, and ordinary herdsmen had little resource against exorbitant taxation and levies. In the 19th century, agriculture had been spread in the steppe and pastureland was increasingly converted to agricultural use. Even during the 18th century growing number of Han settlers had already illegally begun to move into the Inner Mongolian steppe and to lease land from monasteries and banner princes, slowing diminishing the grazing areas for the Mongols' livestock. While alienation of pasture in this way was largely illegal, the practice continued unchecked. By 1852, Han Chinese merchants had deeply penetrated Inner Mongolia, and the Mongols had run up unpayable debts. The monasteries had taken over substantial grazing lands, and monasteries, merchants and banner princes had leased many pasture lands to Han Chinese as farmland, although there was also popular resentment against oppressive taxation, Han settlement, shrinkage of pasture, as well as debts and abuse of the banner princes' authority. Many impoverished Mongols also began to take up farming in the steppe, renting farmlands from their banner princes or from Han merchant landlords who had acquired them for agriculture as settlement for debts. Anyway, the Qing attitude towards Han Chinese colonization of Mongolian lands grew more and more favorable under pressure of events, particularly after the Amur Annexation by Russia in 1860. This would reach a peak during the early 20th century, under the name of "New Policies" or "New Administration" (xinzheng).

Tibetan Buddhism

After the invitation of the 3rd Dalai Lama to Mongolia and conversion of Altan Khan, king of the Tümed Mongols in 1578, nearly all Mongols had become Buddhist within 50 years, including tens of thousands of monks, almost all followers of the Gelug school and loyal to the Dalai Lama. During Hong Taiji's campaign against the last Mongol khan Ligdan Khan, he took on more and more the trappings of a universal king, including the sponsorship of the Tibetan Buddhism that the Mongols believed in. In private however, he viewed the belief in the Buddhist faith by the Mongols with disdain and thought to be destructive to Mongol identity; he said "The Mongolian princes are abandoning the Mongolian language; their names are all in imitation of the lamas".[33] The Manchu leaders themselves like Hung Taiji did not personally believe in Tibetan Buddhism and did not want to convert, in fact the words "incorrigibles" and liars" were used to describe the Lamas by Hung Taiji,[34] however Hung Taiji patronized Buddhism in order to exploit the Tibetans and Mongols belief in the religion.[35] According to the Manchu historian Jin Qicong, Buddhism was used by Qing rulers to control Mongolians and Tibetans; it was of little relevance to ordinary Manchus in the Qing dynasty.[36]

The Tibetan Buddhism was adored by the Qing court. The long association of the Manchu rulership with the Bodhisattva Manjusri and his own interest in Tibetan Buddhism gave credence to the Qianlong Emperor's patronage of Tibetan Buddhist art and patronage of translations of the Buddhist canon. The accounts in court records and Tibetan language sources affirm his personal commitment. He quickly learned to read the Tibetan language and studied Buddhist texts assiduously. His beliefs are reflected in the Tibetan Buddhist imagery of his tomb, perhaps the most personal and private expression of an emperor's life. He supported the Yellow Church (the Tibetan Buddhist Gelukpa sect) to "maintain peace among the Mongols" since the Mongols were followers of the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama of the Yellow Church, and Qianlong had this explanation placed in the Yonghe Temple in Beijing on a stele entitled "Lama Shuo" (on Lamas) in 1792, and he also said it was "merely in pursuance of Our policy of extending Our affection to the weak." which led him to patronize the Yellow Church.[37] Mark Elliott concludes that these actions delivered political benefits but "meshed seamlessly with his personal faith."

Qianlong turned the Palace of Harmony (Yonghegong) into a Tibetan Buddhist temple for Mongols in 1744 and had an edict inscribed on a stele to commemorate it in Tibetan, Mongolian, Chinese, and Manchu, with most likely Qianlong having first wrote the Chinese version before the Manchu.[38]

The Khalkha nobles' power was deliberately undermined by Qianlong when he appointed the Tibetan Ishi-damba-nima of the Lithang royal family of the eastern Tibetans as the 3rd reincarnated Jebtsundamba instead of the Khalkha Mongol which they wanted to be appointed.[39] The decision was first protested against by the Outer Mongol Khalkha nobles and then the Khalkhas sought to have him placed at a distance from them at Dolonnor, but Qianlong snubbed both of their requests, sending the message that he was putting an end to Outer Mongolian autonomy.[40] The decision to make Tibet the only place where the reincarnation came from was intentional by the Qing to curtail the Mongols.[41]

The Bogda Khan Mountain had silk, candles, and incense sent to it from Urga by the two Qing ambans.[42]

The Jebtsundamba and Panchen Lama were referred to as bogda by the Mongols.[43]

Annually Mongol nobles had to pay a visit to the Qing Emperor who was referred to as "Bogda Khan", in Beijing.[44]

The term "Bogda Khan" or "Bogda Khakan" was used by the Mongols to refer to the Emperor (Hwang-ti).[45]

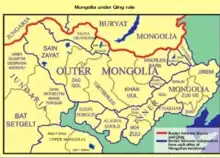

Administrative divisions

Mongolia during Qing period was divided into two main parts: Inner (Manchu: Dorgi) Mongolia and Outer (Manchu: Tülergi) Mongolia. The division affected today's separation of modern Mongolia and Inner Mongolian Autonomous Region of China. In addition to the Outer Mongolian 4 aimags and Inner Mongolian 6 leagues, there were also large areas such as the Khobdo frontier and the guard post zone along the Russian border where Qing administration exercised more direct control.

Inner Mongolia[46] Inner Mongolia's original 24 Aimags were torn apart and replaced by 49 khoshuus (banners) which would later be organized into six chuulgans (leagues, assemblies). The eight Chakhar khoshuus and the two Tümed khoshuus around Guihua were directly administered by the Qing government.

- Jirim league

- Josotu league

- Juu Uda league

- Shilingol league

- Ulaan Chab league

- Ihe Juu league

Plus, followings were directly controlled by the Qing emperor.

- Chakhar 8 khoshuu

- Guihua (Hohhot) Tümed 2 khoshuu

Outer Mongolia

- Khalkha

- Secen Khan aimag 23 khoshuu

- Tüsheetu Khan aimag 20 khoshuu

- Sain Noyon Khan aimag 24 khoshuu

- Zasagtu Khan aimag 19 khoshuu

- Khövsgöl[47]

- Tannu Uriankhai

- Kobdo Territory 30 khoshuu

- Ili 13 khoshuu (in modern-day Xinjiang)

- Khökh Nuur 29 khoshuu (Qinghai)

West Hetao Mongolia

- Ejine khoshuu (modern day Ejina banner in Alxa aimag, Inner Mongolia)

- Alasha khoshuu (modern day Alxa left and right banners in Alxa aimag, Inner Mongolia)

Culture in Mongolia under Qing rule

While the majority of the Mongolian population during this period was illiterate, the Mongols did produce some excellent literature. Literate Mongols in the 19th century produced many historical writings in both Mongolian and Tibetan and considerable work in philology. This period also saw many translations from Chinese and Tibetan fiction.

Hüree Soyol (Hüree culture)

During Qing era, Hüree (modern day Ulaanbaatar, capital of Mongolia) was home for rich culture. Hüree style songs constitute a large amount of the Mongolian traditional culture; some examples include "Alia Sender", "Arvan Tavnii Sar", "Tsagaan Sariin Shiniin Negen", "Zadgai Tsagaan Egule" and many more.

Scholarship in Mongolia during Qing period

Many books including chronicles and poems were written by the Mongols during the Qing period. Notable ones include:

- Altan Tobchi (Golden Chronicle) by Lubsandanzan

- Höh Sudar (The Blue Sutra) by Borjigin Vanchinbaliin Injinashi

See also

Notes

- It was the de facto capital of Outer Mongolia because the Qing Amban located its headquarters in Uliastai to keep eye on the Khalkhas and the Oirats.

References

Citations

- The Cambridge History of China, vol10, pg49

- Paula L. W. Sabloff- Modern mongolia: reclaiming Genghis Khan, p. 32.

- Elverskog, Johan (2006). Our Great Qing: The Mongols, Buddhism, And the State in Late Imperial China (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 14. ISBN 0824830210.

- Marriage and inequality in Chinese society By Rubie Sharon Watson, Patricia Buckley Ebrey, p.177

- Tumen jalafun jecen akū: Manchu studies in honour of Giovanni Stary By Giovanni Stary, Alessandra Pozzi, Juha Antero Janhunen, Michael Weiers

- Dunnell 2004, p. 77.

- Dunnell 2004, p. 83.

- Elliott 2001, p. 503.

- Dunnell 2004, pp. 76-77.

- Cassel 2011, p. 205.

- Cassel 2012, p. 205.

- Cassel 2011, p. 44.

- Cassel 2012, p. 44.

- Zhao 2006, pp. 14.

- Perdue 2009, p. 218.

- Perdue 2009, p. 127.

- Peterson 2002, p. 31.

- Bulag 2012, p. 41.

- Charleux, Isabelle (2015). Nomads on Pilgrimage: Mongols on Wutaishan (China), 1800-1940. BRILL. p. 15. ISBN 978-9004297784.

- Reardon-Anderson, James (Oct 2000). "Land Use and Society in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia during the Qing Dynasty". Environmental History. 5 (4): 506. doi:10.2307/3985584. JSTOR 3985584.

- Rawski 1998, p. 67.

- Black 1991, p. 47.

- Elvin 1998, p. 241.

- Twitchett 1978, p. 356.

- Tsai, Wei-chieh (June 2017). MONGOLIZATION OF HAN CHINESE AND MANCHU SETTLERS IN QING MONGOLIA, 1700–1911 (PDF) (Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Central Eurasian Studies, Indiana University). ProQuest LLC. p. 7.

- Liu, Xiaoyuan (2006). Reins of Liberation: An Entangled History of Mongolian Independence, Chinese Territoriality, and Great Power Hegemony, 1911-1950 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0804754268.

- BORJIGIN, BURENSAIN. “The Complex Structure of Ethnic Conflict in the Frontier: Through the Debates around the 'Jindandao Incident' in 1891.” Inner Asia, vol. 6, no. 1, 2004, pp. 41–60. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/23615320.

- Porter, David. "Ethnic and Status Identity in Qing China: The Hanjun Eight Banners." PhD Diss. Harvard University, 2008. pp. 227-229

- Porter, pp. 226-227

- Porter, p. 226

- Sneath, David (2007). The Headless State: Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, and Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner Asia (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-0231511674.

- Sneath, David (2007). The Headless State: Aristocratic Orders, Kinship Society, and Misrepresentations of Nomadic Inner Asia (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. pp. 105, 106. ISBN 978-0231511674.

- Wakeman Jr. 1986, p. 203.

- The Cambridge History of China: Pt. 1 ; The Ch'ing Empire to 1800. Cambridge University Press. 1978. pp. 64–. ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- The Cambridge History of China: Pt. 1 ; The Ch'ing Empire to 1800. Cambridge University Press. 1978. pp. 65–. ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- Jin, Qicong (2009). 金启孮谈北京的满族 (Jin Qicong Talks About Beijing Manchus). Zhonghua Book Company. p. 95. ISBN 978-7101068566.

- Elisabeth Benard, "The Qianlong Emperor and Tibetan Buddhism," in Dunnell & Elliott & Foret & Millward 2004, pp. 123-4.

- Berger 2003, p. 34.

- Berger 2003, p. 26.

- Berger 2003, p. 17.

- John Man (4 August 2009). The Great Wall: The Extraordinary Story of China's Wonder of the World. Da Capo Press, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-7867-3177-0.

- Isabelle Charleux (29 June 2015). Nomads on Pilgrimage: Mongols on Wutaishan (China), 1800-1940. BRILL. pp. 59–. ISBN 978-90-04-29778-4.

- International Association for Tibetan Studies. Seminar (2007). The Mongolia-Tibet Interface: Opening New Research Terrains in Inner Asia : PIATS 2003 : Tibetan Studies : Proceedings of the Tenth Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Oxford, 2003. BRILL. pp. 212–. ISBN 978-90-04-15521-3.

- Johan Elverskog (2006). Our Great Qing: The Mongols, Buddhism, And the State in Late Imperial China. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-0-8248-3021-2.

- Michie Forbes Anderson Fraser (1924). Tanggu meyen and other Manchu reading lessons: Romanised text and English translation side by side. Luzac & co. p. 182.

- Michael Weiers (editor) Die Mongolen. Beiträge zu ihrer Geschichte und Kultur, Darmstadt 1986, p. 416ff

- Ch. Banzragch, Khövsgöl aimgiin tüükh, Ulaanbaatar 2001, p. 244 (map)

Sources

- Berger, Patricia Ann (2003). Empire of Emptiness: Buddhist Art and Political Authority in Qing China (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0824825638. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Cassel, Par Kristoffer (2011). Grounds of Judgment: Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth-Century China and Japan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199792122. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Cassel, Par Kristoffer (2012). Grounds of Judgment: Extraterritoriality and Imperial Power in Nineteenth-Century China and Japan (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199792054. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dvořák, Rudolf (1895). Chinas religionen ... Volume 12, Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Aschendorff (Druck und Verlag der Aschendorffschen Buchhandlung). ISBN 978-0199792054. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Dunnell, Ruth W.; Elliott, Mark C.; Foret, Philippe; Millward, James A (2004). New Qing Imperial History: The Making of Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134362226. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Elliott, Mark C. (2001). The Manchu Way: The Eight Banners and Ethnic Identity in Late Imperial China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804746847. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Elverskog, Johan. Our Great Qing: The Mongols, Buddhism and the State in Late Imperial China. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2006.

- Hauer, Erich (2007). Corff, Oliver (ed.). Handwörterbuch der Mandschusprache. Volume 12, Volume 15 of Darstellungen aus dem Gebiete der nichtchristlichen Religionsgeschichte (illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447055284. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Lopez, Donald S. (1999). Prisoners of Shangri-La: Tibetan Buddhism and the West (reprint, revised ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226493114. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Millward, James A. (1998). Beyond the Pass: Economy, Ethnicity, and Empire in Qing Central Asia, 1759-1864 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0804729338. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Perdue, Peter C (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia (reprint ed.). Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674042025. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Peterson, Willard J. (2002). the Cambridge History of China, the Ch'ing dynasty to 1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24334-6.

- Reardon-Anderson, James (Oct 2000). "Land Use and Society in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia during the Qing Dynasty". Environmental History. 5 (4): 503–530. doi:10.2307/3985584. JSTOR 3985584.

- WAKEMAN JR., FREDERIC (1986). GREAT ENTERPRISE. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520048041. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Wu, Shuhui (1995). Die Eroberung von Qinghai unter Berücksichtigung von Tibet und Khams 1717 - 1727: anhand der Throneingaben des Grossfeldherrn Nian Gengyao. Volume 2 of Tunguso Sibirica (reprint ed.). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447037563. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Zhao, Gang (January 2006). "Reinventing China Imperial Qing Ideology and the Rise of Modern Chinese National Identity in the Early Twentieth Century". Modern China. 32 (1): 3–30. doi:10.1177/0097700405282349. JSTOR 20062627. S2CID 144587815.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mongolia 1691-1911. |

.svg.png.webp)

.png.webp)