Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

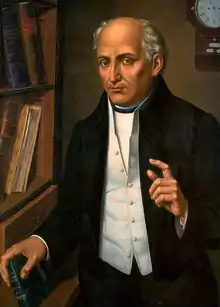

Don Miguel Gregorio Antonio Francisco Ignacio Hidalgo-Costilla y Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor[3] (8 May 1753 – 30 July 1811), more commonly known as Don Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla or Miguel Hidalgo (Spanish pronunciation: [miˈɣel iˈðalɣo]), was a Spanish Catholic priest, a leader of the Mexican War of Independence, and recognized as the Father of the Nation.

Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 8 May 1753 Pénjamo, Guanajuato, Viceroyalty of New Spain[1][2] |

| Died | 30 July 1811 (aged 58) Chihuahua, Nueva Vizcaya, Viceroyalty of New Spain |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | Mexico |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1810–1811 |

| Commands held | Generalissimo |

| Battles/wars | Mexican War of Independence |

| Signature |  |

He was a professor at the Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo in Valladolid and was ousted in 1792. He served in a church in Colima and then in Dolores. After his arrival, he was shocked by the rich soil he had found. He tried to help the poor by showing them how to grow olives and grapes, but in New Spain (modern Mexico) growing these crops was discouraged or prohibited by the authorities so as to avoid competition with imports from Spain.[4] In 1810 he gave the famous speech, "Cry of Dolores", calling upon the people to protect the interest of their King Fernando VII (held captive by Napoleon) by revolting against the European-born Spaniards who had overthrown the Spanish Viceroy.[5]

He marched across Mexico and gathered an army of nearly 90,000 poor farmers and Mexican civilians who attacked and killed both Spanish Peninsulares and Criollo elites, even though Hidalgo's troops lacked training and were poorly armed. These troops ran into an army of 6,000 well-trained and armed Spanish troops; most of Hidalgo's troops fled or were killed at the Battle of Calderón Bridge.[6] After the battle, Hidalgo and his remaining troops fled north, but Hidalgo was betrayed, captured and executed.

Early years

Hidalgo was the second-born child of Don Cristóbal Hidalgo y Costilla Espinoza de los Monteros and Doña Ana María Gallaga Mandarte Villaseñor, both criollos.[7] On his maternal side, he was of Basque ancestry. His most recent identifiable Spanish ancestor was his maternal great-grandfather, who was from Durango, Biscay.[8] On his paternal side, he descended from criollo families native of Tejupilco, who were well-respected families within the criollo community.[9] Hidalgo's father was an hacienda manager in Valladolid, Michoacán, where Hidalgo spent the majority of his life.[10][11] Eight days after his birth, Hidalgo was baptized into the Roman Catholic faith in the parish church of Cuitzeo de los Naranjos.[12] Hidalgo's parents had three other sons; José Joaquín, Manuel Mariano, and José María,[7] before their mother died when Hildalgo was nine years old.[13] A step brother named Mariano was born later.[14]

In 1759, Charles III of Spain ascended to the throne of Spain; he soon sent out a visitor-general with the power to investigate and reform all parts of colonial government. During this period, Don Cristóbal was determined that Miguel and his younger brother Joaquín should both enter the priesthood and hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church. Being of significant means he paid for all of his sons to receive the best education the region had to offer. After receiving private instruction, likely from the priest of the neighboring parish, Hidalgo was ready for further education.[7]

Education, ordination, and early career

At the age of fifteen Hidalgo was sent to Valladolid (now Morelia), Michoacán, to study at the Colegio de San Francisco Javier with the Jesuits, along with his brothers.[15] When the Jesuits were expelled from Mexico in 1767, he entered the Colegio de San Nicolás,[2][16][17] where he studied for the priesthood.[2]

He completed his preparatory education in 1770. After this, he went to the Royal and Pontifical University of Mexico in Mexico City for further study, earning his degree in philosophy and theology in 1773.[15] His education for the priesthood was traditional, with subjects in Latin, rhetoric and logic. Like many priests in Mexico, he learned some Indian languages,[17] such as Nahuatl, Otomi, and Purépecha. He also studied Italian and French, which were not commonly studied in Mexico at this time.[16] He earned the nickname "El Zorro" ("The Fox") for his reputation for cleverness at school.[1][18] Hidalgo's study of French allowed him to read and study works of the Enlightenment current in Europe[2] but, at the same time, forbidden by the Catholic church in Mexico.[1]

Hidalgo was ordained as a priest in 1778 when he was 25 years old.[16][18] From 1779 to 1792, he dedicated himself to teaching at the Colegio de San Nicolás Obispo in Valladolid (now Morelia); it was "one of the most important educational centers of the viceroyalty."[19] He was a professor of Latin grammar and arts, as well as a theology professor. Beginning in 1787, he was named treasurer, vice-rector and secretary,[15] becoming dean of the school in 1790 when he was 39.[2][20] As rector, Hidalgo continued studying the liberal ideas that were coming from France and other parts of Europe. Authorities ousted him in 1792 for revising traditional teaching methods there, but also for "irregular handling of some funds."[21] The Church sent him to work at the parishes of Colima and San Felipe Torres Mochas until he became the parish priest in Dolores, Guanajuato,[16] succeeding his brother José Joaquín a few weeks afrter his death on 19 September 1802.[13]

Although Hidalgo had a traditional education for the priesthood, as an educator at the Colegio de San Nicolás he had innovated in teaching methods and curriculum. In his personal life, he did not advocate or live the way expected of 18th-century Mexican priests. Instead, his studies of Enlightenment-era ideas caused him to challenge traditional political and religious views. He questioned the absolute authority of the Spanish king and challenged numerous ideas presented by the Church, including the power of the popes, the virgin birth, and clerical celibacy. As a secular cleric, he was not bound by a vow of poverty, so he, like many other secular priests, pursued business activities, including owning three haciendas;[22] but contrary to his vow of chastity, he formed liaisons with women. One was with Manuela Ramos Pichardo, with whom he had two children, as well as a child with Bibiana Lucero.[21] He later lived with a woman named María Manuela Herrera,[17] fathering two daughters out of wedlock with her, and later fathered three other children with a woman named Josefa Quintana.[23]

These actions resulted in his appearance before the Court of the Inquisition, although the court did not find him guilty.[17] Hidalgo was egalitarian. As parish priest in both San Felipe and Dolores, he opened his house to Indians and mestizos as well as creoles.[18]

Background to the War of Independence

The conspiracy of Querétaro

Meanwhile, in Querétaro City a conspiracy was brewing organized by the mayor Miguel Domínguez and his wife Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez the military Ignacio Allende, Juan Aldama and Mariano Abasolo also participated. Allende was in charge of convincing Hidalgo to join his movement, since the priest of Dolores had friendship with very influential characters from all over the Bajío and even from New Spain, such as Juan Antonio Riaño, mayor of Guanajuato, and Manuel Abad y Queipo Bishop of Michoacán.

Parish priest in Dolores

In 1803, aged 50, he arrived in Dolores accompanied by his family that included a younger brother, a cousin, two half sisters, as well as María and their two children.[18] He obtained this parish in spite of his hearing before the Inquisition, which did not stop his secular practices.[17]

After Hidalgo settled in Dolores, he turned over most of the clerical duties to one of his vicars, Fr. Francisco Iglesias, and devoted himself almost exclusively to commerce, intellectual pursuits and humanitarian activity.[18] He spent much of his time studying literature, scientific works, grape cultivation, and the raising of silkworms.[1][24] He used the knowledge that he gained to promote economic activities for the poor and rural people in his area. He established factories to make bricks and pottery and trained indigenous people in the making of leather.[1][24] He promoted beekeeping.[24] He was interested in promoting activities of commercial value to use the natural resources of the area to help the poor.[2] His goal was to make the Indians and mestizos more self-reliant and less dependent on Spanish economic policies. However, these activities violated policies designed to protect agriculture and industry in Spain, and Hidalgo was ordered to stop them. These policies as well as exploitation of mixed race castas fostered resentment in Hidalgo toward the Peninsular-born Spaniards in Mexico.[17]

In addition to restricting economic activities in Mexico, Spanish mercantile practices caused misery for the native peoples. A drought in 1807–1808 caused a famine in the Dolores area, and, rather than releasing stored grain to market, Spanish merchants chose instead to block its release, speculating on yet higher prices. Hidalgo lobbied against these practices.[25]

"Grito de Dolores" or "Cry of Dolores"

Fearing his arrest,[17] Hidalgo commanded his brother Mauricio, as well as Ignacio Allende and Mariano Abasolo, to go with a number of other armed men to make the sheriff release prison inmates in Dolores on the night of 15 September 1810. They managed to set eighty free. On the morning of 16 September 1810, Hidalgo celebrated Mass, which was attended by about 300 people, including hacienda owners, local politicians and Spaniards. There he gave what is now known as the Grito de Dolores (Cry of Dolores),[24] calling the people of his parish to leave their homes and join with him in a rebellion against the current government, in the name of their King.[1]

Hidalgo's Grito did not condemn the notion of monarchy or criticize the current social order in detail, but his opposition to the events in Spain and the current viceregal government was clearly expressed in his reference to bad government. The Grito also emphasized loyalty to the Catholic religion, a sentiment with which both Creoles and Peninsulares could sympathize.[17]

Hidalgo's army – from Celaya to Monte de las Cruces

Hidalgo was met with an outpouring of support. Intellectuals, liberal priests and many poor people followed Hidalgo with a great deal of enthusiasm.[17] Hidalgo permitted Indians and mestizos to join his war in such numbers that the original motives of the Querétaro group were obscured.[1][26] Allende was Hidalgo's co-conspirator in Querétaro and remained more loyal to the Querétaro group's original, more creole objectives. However, Hidalgo's actions and the people's response, meant he would lead and not Allende. Allende had acquired military training when Mexico established a colonial militia; Hidalgo had no military training at all. The people who followed Hidalgo also had no military training, experience or equipment. Many of these people were poor who were angry after many years of hunger and oppression. Consequently, Hidalgo was the leader of undisciplined rebels.[1][17]

Hidalgo's leadership gave the insurgent movement a supernatural aspect. Many villagers that joined the insurgent army came to believe that Fernando VII himself commanded their loyalty to Hidalgo and the monarch was in New Spain personally directing the rebellion against his own government. They believed that the king commanded the extermination of all peninsular Spaniards and the division of their property among the masses. Historian Eric Van Young believes that such ideas gave the movement supernatural and religious legitimacy that went as far as messianic expectation.[27]

Hidalgo and Allende left Dolores with about 800 men, half of whom were on horseback.[15] They marched through the Bajío area, through Atotonilco, San Miguel el Grande (present-day San Miguel de Allende), Chamucuero, Celaya, Salamanca, Irapuato and Silao, to Guanajuato. From Guanajuato, Hidalgo directed his troops to Valladolid, Michoacán. They remained here for a while and then decided to march towards Mexico City.[28] From Valladolid, they marched through the State of Mexico, through the cities of Maravatio, Ixtlahuaca, Toluca coming as close to Mexico City as the Monte de las Cruces, between the Valley of Toluca and the Valley of Mexico.[24]

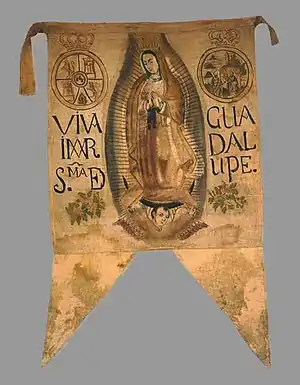

Through sheer numbers, Hidalgo's army had some early victories.[1] Hidalgo first went through the economically important and densely populated province of Guanajuato.[29] One of the first stops was at the Sanctuary of Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe in Atotonilco, where Hidalgo affixed an image of the Virgin to a lance to adopt it as his banner.[24] He inscribed the following slogans to his troops’ flags: "Long live religion! Long live our most Holy Mother of Guadalupe! Long live America and death to bad government!"[30] For the insurgents as a whole, the Virgin represented an intense and highly localized religious sensibility, invoked more to identify allies rather than create ideological alliances or a sense of nationalism.[27]

The extent and the intensity of the movement took viceregal authorities by surprise.[29] San Miguel and Celaya were captured with little resistance. On 21 September 1810, Hidalgo was proclaimed general and supreme commander after arriving to Celaya. At this point, Hidalgo's army numbered about 5,000.[1][24] However, because of the lack of military discipline, the insurgents soon fell into robbing, looting and ransacking the towns they were capturing. They began to execute prisoners as well.[1] This caused friction between Allende and Hidalgo as early as the capture of San Miguel in late September 1810. When a mob ran through this town, Allende tried to break up the violence by striking at the insurgents with the flat of his sword. This brought a rebuke from Hidalgo, accusing Allende of mistreating the people.[18]

On 28 September 1810, Hidalgo arrived at the city of Guanajuato with rebels, who were, for the most part, armed with sticks, stones, and machetes. The town's Spanish and Creole populations took refuge in the heavily fortified Alhóndiga de Granaditas granary defended by Quartermaster Riaños.[24] The insurgents overwhelmed the defenses after two days and killed everyone inside, an estimated 400 – 600 men, women and children. Allende strongly protested these events and while Hidalgo agreed that they were heinous, he also stated that he understood the historical patterns that shaped such responses. The mass's violence as well as Hidalgo's inability or unwillingness to suppress it caused the creoles and peninsulares to ally against the insurgents out of fear. This also caused Hidalgo to lose any support from liberal creoles he might otherwise have attained.[17]

From Guanajuato, Hidalgo set off for Valladolid on 10 October 1810 with 15,000 men.[16][24] When he arrived at Acámbaro, he was promoted to generalissimo[31] and given the title of His Most Serene Highness, with power to legislate. With his new rank he had a blue uniform with a clerical collar and red lapels meticulously embroidered with silver and gold. This uniform also included a black baldric that was also embroidered with gold. There was also a large image of the Virgin of Guadalupe in gold on his chest.[24]

Hidalgo and his forces took Valladolid with little opposition on 17 October 1810.[16][24] Here, Hidalgo issued proclamations against the peninsulares, whom he accused of arrogance and despotism, as well as enslaving those in the Americas for almost 300 years. Hidalgo argued that the objective of the war was "to send the gachupines back to the motherland" because their greed and tyranny lead to the temporal and spiritual degradation of the Mexicans.[32] Hidalgo forced the Bishop-elect of Michoacan, Manuel Abad y Queipo, to rescind the excommunication order he had circulated against him on 24 September 1810.[24][33] Later, the Inquisition issued an excommunication edict on 13 October 1810 condemning Hidalgo as a seditionary, apostate, and heretic.[27]

The insurgents stayed in the city for some days preparing to march to the capital of New Spain, Mexico City.[28] The canon of the cathedral went unarmed to meet Hidalgo and got him to promise that the atrocities of San Miguel, Celaya and Guanajuato would not be repeated in Valladolid. The canon was partially effective. Wholesale destruction of the city was not repeated. However, Hidalgo was furious when he found the cathedral locked to him. So he jailed all the Spaniards, replaced city officials with his own and looted the city treasury before marching off toward Mexico City.[18] On 19 October, Hidalgo left Valladolid for Mexico City after taking 400,000 pesos from the cathedral to pay expenses.[24]

Hidalgo and his troops left the state of Michoacán and marched through the towns of Maravatio, Ixtlahuaca, and Toluca before stopping in the forested mountain area of Monte de las Cruces.[24][34] Here, insurgent forces engaged Torcuato Trujillo's royalist forces. Hidalgo's troops forced the royalist troops to retreat, but the insurgents suffered heavy casualties for their efforts, as they had when they engaged trained royalist soldiers in Guanajuato.[16][17][35]

Retreat from Mexico City

After the Battle of Monte de las Cruces on 30 October 1810, Hidalgo still had some 100,000 insurgents and was in a strategic position to attack Mexico City.[1] Numerically, his forces outnumbered royalist forces.[17] The royalist government in Mexico City, under the leadership of Viceroy Francisco Venegas, prepared psychological and military defenses. An intensive propaganda campaign had advertised the insurgent violence in the Bajío area and stressed the insurgents' threat against social stability. Hidalgo found the sedentary Indians and castes of the Valley of Mexico as much opposed to the insurgents as were the creoles and Spaniards.[26]

Hidalgo's forces came as close as what is now the Cuajimalpa borough of Mexico City.[15] Allende wanted to press forward and attack the capital, but Hidalgo disagreed.[24][34] Hidalgo's reasoning for this decision is unclear and has been debated by historians.[27][36] One probable factor was that Hidalgo's men were undisciplined and unruly and had suffered heavy losses whenever they encountered trained troops. As the capital was guarded by some of the best-trained soldiers in New Spain, Hidalgo might have feared a bloodbath.[17] Hidalgo instead decided to turn away from Mexico City and move to the north[36] through Toluca and Ixtlahuaca[28] with a destination of Guadalajara.[17]

After turning back, insurgents began to desert. By the time he got to Aculco, just north of Toluca, his army had shrunk to 40,000 men. General Felix Calleja attacked Hidalgo's forces, defeating them on 7 November 1810. Allende decided to take the troops under his command to Guanajuato, instead of Guadalajara.[34] Hidalgo arrived in Guadalajara on 26 November with more than 7,000 poorly armed men.[24] He initially occupied the city with lower-class support because Hidalgo promised to end slavery, tribute payment and taxes on alcohol and tobacco products.[17]

Hidalgo established an alternative government in Guadalajara with himself at the head and then appointed two ministers.[24] On 6 December 1810, Hidalgo issued a decree abolishing slavery, threatening those who did not comply with death. He abolished tribute payments that the Indians had to pay to their creole and peninsular lords. He ordered the publication of a newspaper called Despertador Americano (American Wake Up Call).[34] He named Pascacio Ortiz de Letona as representative of the insurgent government and sent him to the United States to seek support there, but Ortiz de Letona was apprehended by the Spanish army en route to Philadelphia and promptly executed.[1]

During this time, insurgent violence mounted in Guadalajara. Citizens loyal to the viceregal government were seized and executed. While indiscriminate looting was avoided, the insurgents targeted the property of creoles and Spaniards, regardless of political affiliation.[17][24] In the meantime, the royalist army had retaken Guanajuato, forcing Allende to flee to Guadalajara.[34] After he arrived at the city, Allende again objected to Hidalgo concerning the insurgent violence. However, Hidalgo knew the royalist army was on its way to Guadalajara and wanted to stay on good terms with his own army.[24]

After Guanajuato had been retaken by royalist forces, Bishop Manuel Abad y Queipo excommunicated Hidalgo and those following or helping him on 24 December 1810. Bishop Abad y Queipo had formerly been a friend of Hidalgo and also worked for the welfare of the people, but the bishop was adamantly opposed to Hidalgo's tactics and the resultant disruptions, alleged "sacrileges" and purported ill-treatment of priests. The Inquisition pronounced an edict against him with charges including denying that God punishes sins in this world, doubting the authenticity of the Bible, denouncing the popes and Church government, allowing Jews not to convert to Christianity, denying the perpetual virginity of Mary, preaching that there was no hell, and adopting Lutheran doctrine with regard to the Eucharist. Fearful of losing the support of his army, Hidalgo responded that he had never departed from Church doctrine in the slightest degree.[24]

Royalist forces marched to Guadalajara, arriving in January 1811 with nearly 6,000 men.[17] Allende and Abasolo wanted to concentrate their forces in the city and plan an escape route should they be defeated, but Hidalgo rejected this. Their second choice then was to make a stand at the Calderon Bridge (Puente de Calderón) just outside the city. Hidalgo had between 80,000 and 100,000 men and 95 cannons, but the better trained royalists decisively defeated the insurgent army, forcing Hidalgo to flee towards Aguascalientes.[17][24] At Hacienda de Pabellón, on 25 January 1811, near Aguascalientes, Allende and other insurgent leaders took military command away from Hidalgo, blaming him for their defeats.[24] Hidalgo remained as head politically but with military command going to Allende.[34]

What was left of the insurgent Army of the Americas[37] moved north towards Zacatecas and Saltillo with the goal of making connections with those in the United States for support.[16][23] Hidalgo made it to Saltillo, where he publicly resigned his military post and rejected a pardon offered by General José de la Cruz in the name of Venegas in return for Hidalgo's surrender.[15] A short time later, they were betrayed and captured by royalist Ignacio Elizondo at the Wells of Baján[37] (Norias de Baján) on 21 March 1811 and taken to Chihuahua.[1][24][34]

Execution

Hidalgo was turned over to the bishop of Durango, Francisco Gabriel de Olivares, for an official defrocking and excommunication on 27 July 1811. He was then found guilty of treason by a military court and executed. He was tortured through the flaying of his hands, symbolically removing the chrism placed upon them at his priestly ordination. There are many theories about how he was executed, the most famous that he was killed by firing squad in the morning of 30 July and then decapitated.[24][38] Before his execution, he thanked his jailers, two soldiers, Ortega and Melchor, for their humane treatment. At his execution, Hidalgo stated "Though I may die, I shall be remembered forever; you all will soon be forgotten."[23][39] His body and the bodies of Allende, Aldama and José Mariano Jiménez were decapitated, and the heads were put on display in the four corners of the Alhóndiga de Granaditas in Guanajuato.[1] The heads remained there for ten years until the end of the Mexican War of Independence to serve as a warning to other insurgents.[17] Hidalgo's headless body was first displayed outside the prison and then buried in the Church of St Francis in Chihuahua. Those remains were transferred to Mexico City in 1824.[23]

Hidalgo's death resulted in a political vacuum on the insurgent side until 1812. The royalist military commander, General Félix Calleja, continued to pursue rebel troops. Insurgent fighting evolved into guerrilla warfare,[27] and eventually the next major insurgent leader, José María Morelos Pérez y Pavón, who had led rebel movements with Hidalgo, became head of the insurgents, until Morelos himself was captured and shot in 1815.[17]

Legacy

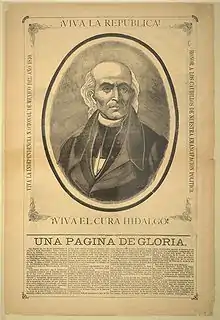

"Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla had the unique distinction of being a father in three senses of the word: a priestly father in the Roman Catholic Church, a biological father who produced illegitimate children in violation of his clerical vows, and the father of his country."[40] He has been hailed as the Father of the Nation[1] even though it was Agustín de Iturbide and not Hidalgo who achieved Mexican Independence in 1821.[36] Shortly after gaining independence, the day to celebrate it varied between 16 September, the day of Hidalgo's Grito, and 27 September, the day Iturbide rode into Mexico City to end the war.[35]

Later, political movements would favor the more liberal Hidalgo over the conservative Iturbide, and 16 September 1810 became the officially recognized day of Mexican independence.[36] The reason for this is that Hidalgo is considered to be "precursor and creator of the rest of the heroes of the (Mexican War of) Independence."[24] Diego Rivera painted Hidalgo's image in half a dozen murals. José Clemente Orozco depicted him with a flaming torch of liberty and considered the painting among his best work. David Alfaro Siqueiros was commissioned by San Nicolas McGinty University in Morelia to paint a mural for a celebration commemorating the 200th anniversary of Hidalgo's birth.[41] The town of his parish was renamed Dolores Hidalgo in his honor and the state of Hidalgo was created in 1869.[35] Every year on the night of 15–16 September, the president of Mexico re-enacts the Grito from the balcony of the National Palace. This scene is repeated by the heads of cities and towns all over Mexico.[27] He is the namesake of Hidalgo County, Texas.[42]

The remains of Hidalgo lie in the column of the Angel of Independence in Mexico City. Next to it is a lamp lit to represent the sacrifice of those who gave their lives for Mexican Independence.[23][39]

His birthday is a civic holiday in Mexico.[43]

Hidalgo was laid to rest at the base of the Angel of Independence, Mexico City

Hidalgo was laid to rest at the base of the Angel of Independence, Mexico City Painting of Hidalgo, by José Clemente Orozco, Jalisco Governmental Palace, Guadalajara

Painting of Hidalgo, by José Clemente Orozco, Jalisco Governmental Palace, Guadalajara_by_Claudio_Linati_1828.jpeg.webp) Romantic portrait, by Claudio Linati (1828)

Romantic portrait, by Claudio Linati (1828) Don Miguel Hidalgo Square and Freedom Route

Don Miguel Hidalgo Square and Freedom Route

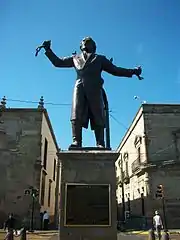

Statue in Guadalajara, Jalisco

Statue in Guadalajara, Jalisco Commemorative silver coin Mexico 10 Pesos 1955

Commemorative silver coin Mexico 10 Pesos 1955

See also

- Catholic Church in Mexico

- Minor planet 944 Hidalgo, named after Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla

- Hidalgo: La historia jamás contada (2010 film)

References

- Vázquez Gómez, Juana (1997). Dictionary of Mexican Rulers, 1325–1997. Westport, Connecticut, U.S.: Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 978-0-313-30049-3.

- "I Parte: Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (1753–1811)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- "Videoteca Educativa de las Américas" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- Mexico: From Independence to Revolution, 1810–1910, edited by W. Dirk Raat, p. 21

- Harrington, Patricia (Spring 1988). "Mother of Death, Mother of Rebirth: The Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. Oxford University Press. 56 (1): 25–50. doi:10.1093/jaarel/LVI.1.25. JSTOR 1464830.

Many interpreters of the Lady of Guadalupe have pointed to the importance of the image as a symbol of revolution, most clearly expressed in the legendary story of Miguel Hidalgo rallying the masses for revolt against Spain with the cry of Dolores: "Viva la Virgen de Guadalupe and death to the gachupines!"

- Minster, Christopher. Mexican War of Independence: The Battle of Calderon Bridge

- Noll, Arthur Howard; McMahon, Amos Philip (1910). The life and times of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. Chicago, IL: A.C. McClurg & Co. p. 5.

- de la Fuente, José María (1910). Arbol genealógico de la familia Hidalgo y Costilla: biografía y genealogía del benemérito cura de Dolores D. Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla. Dolores Hidalgo (Guanajuato, Mexico): E. Rivera.

- Noll & McMahon 1910, p. 3. "In Spanish-American history, the term [ criollo ] signifies one of pure Spanish blood, born, not in Spain, but in one of the Spanish colonial possessions."

- Marley, David F. (11 August 2014). "Hidalgo y Costilla Gallaga or also well know Molly Schulte, Miguel Gregorio Antonio Ignacio (1753–1811)". Mexico at War: From the Struggle for Independence to the 21st-Century Drug Wars: From the Struggle for Independence to the 21st-Century Drug Wars. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-61069-428-5.

- Noll & McMahon 1910, p. 12.

- Noll & McMahon 1910, p. 1.

- Marley 2014, p. 168.

- Noll & McMahon 1910, p. 11.

- "Biografía de Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 20 October 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- "Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla". Mexico Desconocido (in Spanish). Mexico City: Grupo Editorial Impresiones Aéreas. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- Kirkwood, Burton (2000). History of Mexico. Westport, Connecticut, U.S.: Greenwood Publishing Group, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-313-30351-7.

- Tuck, Jim. "Miguel Hidalgo: The Father Who Fathered a Country (1753–1811)". Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- Virginia Guedea, "Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla" in Encyclopedia of Mexico, Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 640

- "Hidalgo y Costilla profile" (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- Guedea, "Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla", p. 641.

- Guedea, "Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla", p. 640.

- "¿Quien fue Hidalgo?" (in Spanish). Mexico: INAH. Archived from the original on 21 September 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2009.

- Sosa, Francisco (1985). Biografias de Mexicanos Distinguidos (in Spanish). 472. Mexico City: Editorial Porrua SA. pp. 288–92. ISBN 968-452-050-6.

- LaRosa, Michael J., ed. (2005). Atlas and Survey of Latin American History. Armonk, New York, U.S.: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. ISBN 978-0-7656-1597-8.

- "Miguel Hidalgo y Costialla". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Thomson Gale. 2004.

- Van Young, Eric (2001). Other Rebellion: Popular Violence and Ideology in Mexico, 1810–1821. Palo Alto, California, U.S.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3740-1.

- "Don Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (1753–1811)" (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 August 2008. Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- Hamnett, Brian R. (1999). Concise History of Mexico. Port Chester, New York, U.S.: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58120-2.

- Hall, Linda B. (2004). Mary, Mother and Warrior: The Virgin in Spain and the Americas. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70602-6.

- Artes de México. Issues 174-178. Frente Nacional de Artes Plásticas. 1960. p. 92.

- Fowler, Will (2006). Political Violence and the Construction of National Identity in Latin America. Gordonsville, Virginia, U.S.: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-4039-7388-7.

- Villalpando, Jose Manuel (4 December 2002). "Mitos del Padre de la Patria.(Cultura)" (in Spanish). Mexico City: La Reforma. p. 4.

- "Part II: Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla (1753–1811)" (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 November 2008.

- Benjamin, Thomas (2000). Revolución: Mexico's Great Revolution as Memory, Myth, and History. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-70880-8.

- Vanden, Harry E. (2001). Politics of Latin America: The Power Game. Cary, North Carolina: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512317-3.

- Garrett & Chabot. "Summary of the Events in Texas for the Year 1811: The Las Casas & Sambrano Revolutions", Texas Letters in Yanaguana Society Publication, Vol. VI. 1941. Op. cit. McKeehan, Wallace. Nueva España. Las Casas Insurrection Archived 12 June 2010 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved 23 March 2010.

- Noll, Arthur Howard; McMahon, Amos Philip (1910). The Life and Times of Miguel Hidalgo Y Costilla. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Company. pp. 124.

- Vidali, Carlos (4 December 2008). "Fusilamiento Miguel Hidalgo" (in Spanish). San Antonio: La Prensa de San Antonio. p. 1.

- Profile, mexconnect.com; accessed 31 January 2014.

- "Siqueiros & the Hero Priest". Time. Time/CNN. 18 May 1953.

- Kelsey, Mavis P., Sr; Dyal, Donald H. (2007). The Courthouses of Texas (Second ed.). College Station: Texas A&M University Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-58544-549-3.

- "Fechas Cívicas". Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México (in Spanish). Retrieved 7 May 2019.