Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands

The Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands are a chain of barrier islands in the Gulf of Mexico along the coasts of Mississippi and Alabama enclosing the Mississippi Sound. The major islands are Cat Island, Ship Island, Horn Island, Petit Bois Island, and Dauphin Island. The islands are separated by wide inlets, several of which have been channelized to form the shipping channels for Gulf coast ports. The shapes and sizes of the islands have changed significantly since the 1800s, with the islands generally shrinking and shifting westward, especially after major tropical cyclones. Most of the islands are uninhabited. Much of the Mississippi portion of the chain is included in the Gulf Islands National Seashore.

The Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands and associated tidal inlets in 2007. Before 2019 Ship Island was divided into two smaller islands. | |

Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Gulf of Mexico |

| Coordinates | 30.2°N 88.6°W |

| Total islands | 5 |

| Major islands | Cat Island, Ship Island, Horn Island, Petit Bois Island, Dauphin Island |

| Length | 70 mi (110 km) |

| Administration | |

| States | Mississippi, Alabama |

Geography

The Mississippi–Alabama barrier island chain sits 10 to 14 miles (16 to 23 km) offshore from the Mississippi Gulf Coast and runs parallel to the coast for 70 miles (113 km),[1] roughly from the Bay of St. Louis to Mobile Bay, separating the Mississippi Sound from the Gulf of Mexico. The five main barrier islands, listed from west to east, are Cat Island, Ship Island (both in Harrison County, Mississippi), Horn Island, Petit Bois Island (both in Jackson County, Mississippi), and Dauphin Island (in Mobile County, Alabama).[2]:2 The only significant settlement on the island chain is the town of Dauphin Island, Alabama, which occupies the eastern half of that island; the rest of the islands are uninhabited. Portions of the four Mississippi islands have been included in the Gulf Islands National Seashore since its establishment in 1971.[3]:5

The islands have sandy beaches on both their Gulf and Sound shores; the Gulf side beaches are wider and have finer sands due to the greater wave energy they face. The interiors include areas of sand flats, coastal marshes, dune fields, and brackish ponds.[3]:9 The islands are separated by wide inlets, several of which have been channelized through regular dredging to form deep-draft shipping channels. Ship Island Pass (between Cat Island and Ship Island) includes the shipping channel for Gulfport, Mississippi; Dog Keys Pass (between Ship Island and Horn Island) includes the channel for Biloxi, Mississippi; Horn Island Pass (between Horn Island and Petit Bois Island) includes the channel for Pascagoula, Mississippi; Petit Bois Pass (between Petit Bois Island and Dauphin Island) has not been channelized; finally, the mouth of Mobile Bay, east of Dauphin Island, includes the channel for Mobile, Alabama.[2]:21–23

Geomorphology

The barrier islands are the above-water portions of a nearly continuous sand bar that runs the length of the Mississippi Sound. The bar is thought to have begun forming after about 2500 BCE as the Gulf's mean sea level fell after the Holocene climatic optimum.[2]:2–3 The sand is primarily composed of white quartz, with a medium grain size.[3]:6 The shapes and sizes of the islands have changed significantly since the 1800s, with the islands generally shrinking and drifting westward, in the direction of the predominant longshore current.[2]:1 This littoral current brings sand to the islands from sources to the east, but in recent centuries the chain has generally lost sand on balance over time. This is thought to be a result of a general weakening of the longshore current,[1] together with the effects of man-made shipping channels (especially the Mobile Ship Channel), which function as sediment traps and subtract from the chain's sediment budget.[2]:22–24 The imbalance between sediment erosion and deposition has resulted in the progressive retreat of the islands' shorelines, though the change has not been as rapid among the Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands as among the nearby barrier islands of Louisiana.[4]

Recurring major tropical cyclones have periodically altered the islands' shapes through wind, waves, and accompanying storm surges.[2]:10 Although severe storms often noticeably disrupt the morphologies and ecosystems of the islands on the timescale of days, vegetation and land area normally recover gradually over a period of years following a major weather event.[5] The gradual sea level rise in the Gulf during the past century has contributed to the decrease in land area of the island chain, but the effect is not thought to have been large compared with the influence of the removal of sediment from the system through the dredging of shipping channels.[2]:22–24

Ecology

The interiors of the islands are vegetated, with pine forests on the higher ridges and marsh vegetation in the lower swales.[2]:3–4 The larger islands are inhabited by terrestrial animals such as raccoons and feral pigs, semiaquatic animals such as nutria, resident birds such as osprey, and migratory birds in season.[6] The chain's sandy beaches serve as nesting grounds for Atlantic ridley sea turtles.[3]:18 Along the island chain's north shore are extensive seagrass meadows, including such species as turtle grass, manatee grass, shoal grass, star grass, and wigeon grass. These seagrass beds provide food and habitats for a variety of aquatic fauna, including penaeid shrimp, blue crab, spotted seatrout, and other shellfish and finfish.[7]:77

Islands

Cat Island

Cat Island runs for 3.5 miles (6 km) along the western end of the Mississippi Sound, south of Gulfport. This island has maintained a relatively stable morphology since surveys began, partly due to its relatively high interior elevation. It has a T-shape, with northward and southward spits extending out from its eastern end. Since surveys began, the southward spit has experienced more erosion than the northward one, and all parts of the island have narrowed.[2]:8–9

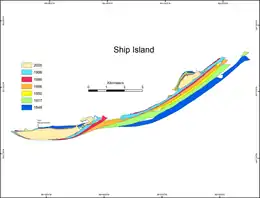

Ship Island

Ship Island runs for 7 miles (11 km) along the western part of the Mississippi Sound, south of Biloxi. This island has experienced major morphological changes over the past two centuries, with its eastern spit rapidly receding, and its narrow central segment shifting toward the mainland. The island's central portion has been repeatedly breached by major storms, most recently by Hurricane Camille in 1969;[2]:8 the so-called "Camille Cut" between the western and eastern portions of the island was filled by the United States Army Corps of Engineers in 2019.[8]

Horn Island

Horn Island runs for 13 miles (21 km) along the central part of the Mississippi Sound. Since surveys began, the island's east end has receded through erosion, while its west end has grown through spit formation at the down-current end. The east end has lost more land than the west has gained, and the island has generally narrowed over the same period.[2]:7

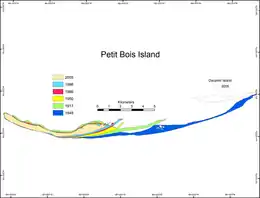

Petit Bois Island

Petit Bois Island runs for 6 miles (10 km) along the eastern part of the Mississippi Sound, south of Pascagoula. This island has undergone the most dramatic morphological changes in the island chain during the past two centuries. The wider triangular segment that now forms the island's eastern end was its extreme western end as recently as the 1840s, but, as with neighboring Horn Island, the eastern spit has receded rapidly, while a new western tail has grown more slowly.[2]:6–7

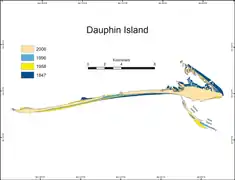

Dauphin Island

Dauphin Island runs for 15 miles (24 km) at the east end of the Mississippi Sound and marks the western edge of the mouth of Mobile Bay. The eastern quarter of the island is wider and more elevated, while the western end is narrow and more prone to disturbance by storms. The east end includes the town of Dauphin Island. Since surveys began, the long western tail has generally lengthened, due to sand deposition from the longshore drift, and shifted toward the mainland, due to erosion on the Gulf shore and overwash during major storms.[2]:5–6

Island maps

Cat Island

Cat Island Ship Island

Ship Island Horn Island

Horn Island Petit Bois Island

Petit Bois Island Dauphin Island

Dauphin Island

References

- Rucker, James B.; Snowden, Jesse O. (1990). "Barrier Island Evolution and Reworking by Inlet Migration along the Mississippi–Alabama Gulf Coast". GCAGS Transactions. American Association of Petroleum Geologists. 40: 745–753. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Morton, Robert A. (2007). "Historical Changes in the Mississippi–Alabama Barrier Islands and the Roles of Extreme Storms, Sea Level, and Human Activities" (PDF). USGS Publications Warehouse. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- "Geologic Resource Evaluation Scoping Summary, Gulf Islands National Seashore". Integrated Resource Management Applications. United States National Park Service. 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- Shabica, Stephen V.; Dolan, Robert; May, Suzette; May, Paul (September 1983). "Shoreline erosion rates along barrier islands of the north central gulf of Mexico". Environmental Geology. 5 (3): 115–126. Bibcode:1983EnGeo...5..115S. doi:10.1007/BF02381269. S2CID 128663473.

- Carter, Gregory A.; Otvos, Ervin G.; Anderson, Carlton P.; Funderburk, William R.; Lucas, Kelly L. (November 15, 2018). "Catastrophic storm impact and gradual recovery on the Mississippi–Alabama barrier islands, 2005–2010: Changes in vegetated and total land area, and relationships of post-storm ecological communities with surface elevation". Geomorphology. Elsevier. 321: 72–86. Bibcode:2018Geomo.321...72C. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2018.08.020.

- Skelton, Zan (1983). "Planning a Visit to the Barrier Islands" (PDF). Mississippi Department of Marine Resources. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- Moncreiff, Cynthia A. (June 2007). "Mississippi Sound and the Gulf Islands". In Handley, L.; Altsman, D.; DeMay, R. (eds.). Seagrass Status and Trends in the Northern Gulf of Mexico: 1940–2002 (PDF). USGS Publications Warehouse. United States Geological Survey. pp. 77–86. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Perez, Mary (September 25, 2019). "Camille Cut is no more. A look at new changes to the barrier islands of the Mississippi Coast". Biloxi Sun Herald. Retrieved October 14, 2020.