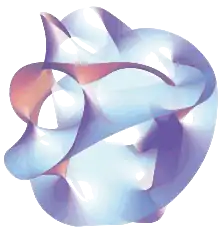

Monstrous moonshine

In mathematics, monstrous moonshine, or moonshine theory, is the unexpected connection between the monster group M and modular functions, in particular, the j function. The term was coined by John Conway and Simon P. Norton in 1979.

| String theory |

|---|

|

| Fundamental objects |

| Perturbative theory |

| Non-perturbative results |

| Phenomenology |

| Mathematics |

It is now known that lying behind monstrous moonshine is a vertex operator algebra called the moonshine module (or monster vertex algebra) constructed by Igor Frenkel, James Lepowsky, and Arne Meurman in 1988, having the monster group as symmetries. This vertex operator algebra is commonly interpreted as a structure underlying a two-dimensional conformal field theory, allowing physics to form a bridge between two mathematical areas. The conjectures made by Conway and Norton were proven by Richard Borcherds for the moonshine module in 1992 using the no-ghost theorem from string theory and the theory of vertex operator algebras and generalized Kac–Moody algebras.

History

In 1978, John McKay found that the first few terms in the Fourier expansion of the normalized J-invariant (sequence A014708 in the OEIS),

with and τ as the half-period ratio could be expressed in terms of linear combinations of the dimensions of the irreducible representations of the monster group M (sequence A001379 in the OEIS) with small non-negative coefficients. Let = 1, 196883, 21296876, 842609326, 18538750076, 19360062527, 293553734298, ... then,

(Since there can be several linear relations between the such as , the representation may be in more than one way.) McKay viewed this as evidence that there is a naturally occurring infinite-dimensional graded representation of M, whose graded dimension is given by the coefficients of J, and whose lower-weight pieces decompose into irreducible representations as above. After he informed John G. Thompson of this observation, Thompson suggested that because the graded dimension is just the graded trace of the identity element, the graded traces of nontrivial elements g of M on such a representation may be interesting as well.

Conway and Norton computed the lower-order terms of such graded traces, now known as McKay–Thompson series Tg, and found that all of them appeared to be the expansions of Hauptmoduln. In other words, if Gg is the subgroup of SL2(R) which fixes Tg, then the quotient of the upper half of the complex plane by Gg is a sphere with a finite number of points removed, and furthermore, Tg generates the field of meromorphic functions on this sphere.

Based on their computations, Conway and Norton produced a list of Hauptmoduln, and conjectured the existence of an infinite dimensional graded representation of M, whose graded traces Tg are the expansions of precisely the functions on their list.

In 1980, A. Oliver L. Atkin, Paul Fong and Stephen D. Smith produced strong computational evidence that such a graded representation exists, by decomposing a large number of coefficients of J into representations of M. A graded representation whose graded dimension is J, called the moonshine module, was explicitly constructed by Igor Frenkel, James Lepowsky, and Arne Meurman, giving an effective solution to the McKay–Thompson conjecture, and they also determined the graded traces for all elements in the centralizer of an involution of M, partially settling the Conway–Norton conjecture. Furthermore, they showed that the vector space they constructed, called the Moonshine Module , has the additional structure of a vertex operator algebra, whose automorphism group is precisely M.

Borcherds proved the Conway–Norton conjecture for the Moonshine Module in 1992. He won the Fields Medal in 1998 in part for his solution of the conjecture.

The monster module

The Frenkel–Lepowsky–Meurman construction starts with two main tools:

- The construction of a lattice vertex operator algebra VL for an even lattice L of rank n. In physical terms, this is the chiral algebra for a bosonic string compactified on a torus Rn/L. It can be described roughly as the tensor product of the group ring of L with the oscillator representation in n dimensions (which is itself isomorphic to a polynomial ring in countably infinitely many generators). For the case in question, one sets L to be the Leech lattice, which has rank 24.

- The orbifold construction. In physical terms, this describes a bosonic string propagating on a quotient orbifold. The construction of Frenkel–Lepowsky–Meurman was the first time orbifolds appeared in conformal field theory. Attached to the –1 involution of the Leech lattice, there is an involution h of VL, and an irreducible h-twisted VLmodule, which inherits an involution lifting h. To get the Moonshine Module, one takes the fixed point subspace of h in the direct sum of VL and its twisted module.

Frenkel, Lepowsky, and Meurman then showed that the automorphism group of the moonshine module, as a vertex operator algebra, is M. Furthermore, they determined that the graded traces of elements in the subgroup 21+24.Co1 match the functions predicted by Conway and Norton (Frenkel, Lepowsky & Meurman (1988)).

Borcherds' proof

Richard Borcherds' proof of the conjecture of Conway and Norton can be broken into the following major steps:

- One begins with a vertex operator algebra V with an invariant bilinear form, an action of M by automorphisms, and with known decomposition of the homogeneous spaces of seven lowest degrees into irreducible M-representations. This was provided by Frenkel–Lepowsky–Meurman's construction and analysis of the Moonshine Module.

- A Lie algebra , called the monster Lie algebra, is constructed from V using a quantization functor. It is a generalized Kac–Moody Lie algebra with a monster action by automorphisms. Using the Goddard–Thorn "no-ghost" theorem from string theory, the root multiplicities are found to be coefficients of J.

- One uses the Koike–Norton–Zagier infinite product identity to construct a generalized Kac–Moody Lie algebra by generators and relations. The identity is proved using the fact that Hecke operators applied to J yield polynomials in J.

- By comparing root multiplicities, one finds that the two Lie algebras are isomorphic, and in particular, the Weyl denominator formula for is precisely the Koike–Norton–Zagier identity.

- Using Lie algebra homology and Adams operations, a twisted denominator identity is given for each element. These identities are related to the McKay–Thompson series Tg in much the same way that the Koike–Norton–Zagier identity is related to J.

- The twisted denominator identities imply recursion relations on the coefficients of Tg, and unpublished work of Koike showed that Conway and Norton's candidate functions satisfied these recursion relations. These relations are strong enough that one only needs to check that the first seven terms agree with the functions given by Conway and Norton. The lowest terms are given by the decomposition of the seven lowest degree homogeneous spaces given in the first step.

Thus, the proof is completed (Borcherds (1992)). Borcherds was later quoted as saying "I was over the moon when I proved the moonshine conjecture", and "I sometimes wonder if this is the feeling you get when you take certain drugs. I don't actually know, as I have not tested this theory of mine." (Roberts 2009, p. 361)

More recent work has simplified and clarified the last steps of the proof. Jurisich (Jurisich (1998), Jurisich, Lepowsky & Wilson (1995)) found that the homology computation could be substantially shortened by replacing the usual triangular decomposition of the Monster Lie algebra with a decomposition into a sum of gl2 and two free Lie algebras. Cummins and Gannon showed that the recursion relations automatically imply the McKay Thompson series are either Hauptmoduln or terminate after at most 3 terms, thus eliminating the need for computation at the last step.

Generalized moonshine

Conway and Norton suggested in their 1979 paper that perhaps moonshine is not limited to the monster, but that similar phenomena may be found for other groups.[lower-alpha 1] While Conway and Norton's claims were not very specific, computations by Larissa Queen in 1980 strongly suggested that one can construct the expansions of many Hauptmoduln from simple combinations of dimensions of irreducible representations of sporadic groups. In particular, she decomposed the coefficients of McKay-Thompson series into representations of subquotients of the Monster in the following cases:

- T2B and T4A into representations of the Conway group Co0

- T3B and T6B into representations of the Suzuki group 3.2.Suz

- T3C into representations of the Thompson group Th = F3

- T5A into representations of the Harada–Norton group HN = F5

- T5B and T10D into representations of the Hall–Janko group 2.HJ

- T7A into representations of the Held group He = F7

- T7B and T14C into representations of 2.A7

- T11A into representations of the Mathieu group 2.M12

Queen found that the traces of non-identity elements also yielded q-expansions of Hauptmoduln, some of which were not McKay–Thompson series from the Monster. In 1987, Norton combined Queen's results with his own computations to formulate the Generalized Moonshine conjecture. This conjecture asserts that there is a rule that assigns to each element g of the monster, a graded vector space V(g), and to each commuting pair of elements (g, h) a holomorphic function f(g, h, τ) on the upper half-plane, such that:

- Each V(g) is a graded projective representation of the centralizer of g in M.

- Each f(g, h, τ) is either a constant function, or a Hauptmodul.

- Each f(g, h, τ) is invariant under simultaneous conjugation of g and h in M, up to a scalar ambiguity.

- For each (g, h), there is a lift of h to a linear transformation on V(g), such that the expansion of f(g, h, τ) is given by the graded trace.

- For any , is proportional to .

- f(g, h, τ) is proportional to J if and only if g = h = 1.

This is a generalization of the Conway–Norton conjecture, because Borcherds's theorem concerns the case where g is set to the identity.

Like the Conway–Norton conjecture, Generalized Moonshine also has an interpretation in physics, proposed by Dixon–Ginsparg–Harvey in 1988 (Dixon, Ginsparg & Harvey (1989)). They interpreted the vector spaces V(g) as twisted sectors of a conformal field theory with monster symmetry, and interpreted the functions f(g, h, τ) as genus one partition functions, where one forms a torus by gluing along twisted boundary conditions. In mathematical language, the twisted sectors are irreducible twisted modules, and the partition functions are assigned to elliptic curves with principal monster bundles, whose isomorphism type is described by monodromy along a basis of 1-cycles, i.e., a pair of commuting elements.

Modular moonshine

In the early 1990s, the group theorist A. J. E. Ryba discovered remarkable similarities between parts of the character table of the monster, and Brauer characters of certain subgroups. In particular, for an element g of prime order p in the monster, many irreducible characters of an element of order kp whose kth power is g are simple combinations of Brauer characters for an element of order k in the centralizer of g. This was numerical evidence for a phenomenon similar to monstrous moonshine, but for representations in positive characteristic. In particular, Ryba conjectured in 1994 that for each prime factor p in the order of the monster, there exists a graded vertex algebra over the finite field Fp with an action of the centralizer of an order p element g, such that the graded Brauer character of any p-regular automorphism h is equal to the McKay-Thompson series for gh (Ryba (1996)).

In 1996, Borcherds and Ryba reinterpreted the conjecture as a statement about Tate cohomology of a self-dual integral form of . This integral form was not known to exist, but they constructed a self-dual form over Z[1/2], which allowed them to work with odd primes p. The Tate cohomology for an element of prime order naturally has the structure of a super vertex algebra over Fp, and they broke up the problem into an easy step equating graded Brauer super-trace with the McKay-Thompson series, and a hard step showing that Tate cohomology vanishes in odd degree. They proved the vanishing statement for small odd primes, by transferring a vanishing result from the Leech lattice (Borcherds & Ryba (1996)). In 1998, Borcherds showed that vanishing holds for the remaining odd primes, using a combination of Hodge theory and an integral refinement of the no-ghost theorem (Borcherds (1998), Borcherds (1999)).

The case of order 2 requires the existence of a form of over a 2-adic ring, i.e., a construction that does not divide by 2, and this was not known to exist at the time. There remain many additional unanswered questions, such as how Ryba's conjecture should generalize to Tate cohomology of composite order elements, and the nature of any connections to generalized moonshine and other moonshine phenomena.

Conjectured relationship with quantum gravity

In 2007, E. Witten suggested that AdS/CFT correspondence yields a duality between pure quantum gravity in (2+1)-dimensional anti de Sitter space and extremal holomorphic CFTs. Pure gravity in 2+1 dimensions has no local degrees of freedom, but when the cosmological constant is negative, there is nontrivial content in the theory, due to the existence of BTZ black hole solutions. Extremal CFTs, introduced by G. Höhn, are distinguished by a lack of Virasoro primary fields in low energy, and the moonshine module is one example.

Under Witten's proposal (Witten (2007)), gravity in AdS space with maximally negative cosmological constant is AdS/CFT dual to a holomorphic CFT with central charge c=24, and the partition function of the CFT is precisely j-744, i.e., the graded character of the moonshine module. By assuming Frenkel-Lepowsky-Meurman's conjecture that moonshine module is the unique holomorphic VOA with central charge 24 and character j-744, Witten concluded that pure gravity with maximally negative cosmological constant is dual to the monster CFT. Part of Witten's proposal is that Virasoro primary fields are dual to black-hole-creating operators, and as a consistency check, he found that in the large-mass limit, the Bekenstein-Hawking semiclassical entropy estimate for a given black hole mass agrees with the logarithm of the corresponding Virasoro primary multiplicity in the moonshine module. In the low-mass regime, there is a small quantum correction to the entropy, e.g., the lowest energy primary fields yield ln(196883) ~ 12.19, while the Bekenstein–Hawking estimate gives 4π ~ 12.57.

Later work has refined Witten's proposal. Witten had speculated that the extremal CFTs with larger cosmological constant may have monster symmetry much like the minimal case, but this was quickly ruled out by independent work of Gaiotto and Höhn. Work by Witten and Maloney (Maloney & Witten (2007)) suggested that pure quantum gravity may not satisfy some consistency checks related to its partition function, unless some subtle properties of complex saddles work out favorably. However, Li–Song–Strominger (Li, Song & Strominger (2008)) have suggested that a chiral quantum gravity theory proposed by Manschot in 2007 may have better stability properties, while being dual to the chiral part of the monster CFT, i.e., the monster vertex algebra. Duncan–Frenkel (Duncan & Frenkel (2009)) produced additional evidence for this duality by using Rademacher sums to produce the McKay–Thompson series as 2+1 dimensional gravity partition functions by a regularized sum over global torus-isogeny geometries. Furthermore, they conjectured the existence of a family of twisted chiral gravity theories parametrized by elements of the monster, suggesting a connection with generalized moonshine and gravitational instanton sums. At present, all of these ideas are still rather speculative, in part because 3d quantum gravity does not have a rigorous mathematical foundation.

Mathieu moonshine

In 2010, Tohru Eguchi, Hirosi Ooguri, and Yuji Tachikawa observed that the elliptic genus of a K3 surface can be decomposed into characters of the N = (4,4) superconformal algebra, such that the multiplicities of massive states appear to be simple combinations of irreducible representations of the Mathieu group M24. This suggests that there is a sigma-model conformal field theory with K3 target that carries M24 symmetry. However, by the Mukai–Kondo classification, there is no faithful action of this group on any K3 surface by symplectic automorphisms, and by work of Gaberdiel–Hohenegger–Volpato, there is no faithful action on any K3 sigma-model conformal field theory, so the appearance of an action on the underlying Hilbert space is still a mystery.

By analogy with McKay–Thompson series, Cheng suggested that both the multiplicity functions and the graded traces of nontrivial elements of M24 form mock modular forms. In 2012, Gannon proved that all but the first of the multiplicities are non-negative integral combinations of representations of M24, and Gaberdiel–Persson–Ronellenfitsch–Volpato computed all analogues of generalized moonshine functions, strongly suggesting that some analogue of a holomorphic conformal field theory lies behind Mathieu moonshine. Also in 2012, Cheng, Duncan, and Harvey amassed numerical evidence of an umbral moonshine phenomenon where families of mock modular forms appear to be attached to Niemeier lattices. The special case of the A124 lattice yields Mathieu Moonshine, but in general the phenomenon does not yet have an interpretation in terms of geometry.

Origin of the term

The term "monstrous moonshine" was coined by Conway, who, when told by John McKay in the late 1970s that the coefficient of (namely 196884) was precisely one more than the degree of the smallest faithful complex representation of the monster group (namely 196883), replied that this was "moonshine" (in the sense of being a crazy or foolish idea).[lower-alpha 2] Thus, the term not only refers to the monster group M; it also refers to the perceived craziness of the intricate relationship between M and the theory of modular functions.

Related observations

The monster group was investigated in the 1970s by mathematicians Jean-Pierre Serre, Andrew Ogg and John G. Thompson; they studied the quotient of the hyperbolic plane by subgroups of SL2(R), particularly, the normalizer Γ0(p)+ of the Hecke congruence subgroup Γ0(p) in SL(2,R). They found that the Riemann surface resulting from taking the quotient of the hyperbolic plane by Γ0(p)+ has genus zero if and only if p is 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, 17, 19, 23, 29, 31, 41, 47, 59 or 71. When Ogg heard about the monster group later on, and noticed that these were precisely the prime factors of the size of M, he published a paper offering a bottle of Jack Daniel's whiskey to anyone who could explain this fact (Ogg (1974)).

Notes

- Conway, J. and Norton, S. "Monstrous Moonshine", Table 2a, p.330, http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.103.3704&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- World Wide Words: Moonshine

Sources

- Borcherds, R. E. (1998), "Modular Moonshine III", Duke Mathematical Journal, 93 (1): 129–154, doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-98-09305-X.

- Borcherds, R. E. (1999), "The Fake Monster Formal Group", Duke Mathematical Journal, 100 (1): 139–165, arXiv:math/9805123, doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-99-10005-6.

- Borcherds, R. E.; Ryba, A. J. E. (1996), "Modular Moonshine II", Duke Mathematical Journal, 83 (2): 435–459, doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-96-08315-5.

- Borcherds, Richard (1992), "Monstrous Moonshine and Monstrous Lie Superalgebras" (PDF), Invent. Math., 109: 405–444, Bibcode:1992InMat.109..405B, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.165.2714, doi:10.1007/bf01232032, MR 1172696.

- Conway, John Horton; Norton, Simon P. (1979). "Monstrous Moonshine". Bull. London Math. Soc. 11 (3): 308–339. doi:10.1112/blms/11.3.308. MR 0554399..

- Cummins, C. J.; Gannon, T (1997). "Modular equations and the genus zero property of moonshine functions". Invent. Math. 129 (3): 413–443. Bibcode:1997InMat.129..413C. doi:10.1007/s002220050167..

- Dixon, L.; Ginsparg, P.; Harvey, J. (1989), "Beauty and the Beast: superconformal symmetry in a Monster module", Comm. Math. Phys., 119 (2): 221–241, Bibcode:1988CMaPh.119..221D, doi:10.1007/bf01217740.

- Du Sautoy, Marcus (2008), Finding Moonshine, A Mathematician's Journey Through Symmetry, Fourth Estate, ISBN 978-0-00-721461-7

- Duncan, John F. R.; Frenkel, Igor B. (2012), Rademacher sums, moonshine and gravity, arXiv:0907.4529, Bibcode:2009arXiv0907.4529D.

- Frenkel, Igor B.; Lepowsky, James; Meurman, Arne (1988). Vertex Operator Algebras and the Monster. Pure and Applied Math. Volume 134. Academic Press. MR 0996026..

- Gannon, Terry (2000), "Monstrous Moonshine and the Classification of Conformal Field Theories", in Saclioglu, Cihan; Turgut, Teoman; Nutku, Yavuz (eds.), Conformal Field Theory, New Non-Perturbative Methods in String and Field Theory, Cambridge Mass: Perseus Publishing, ISBN 0-7382-0204-5 (Provides introductory reviews to applications in physics).

- Gannon, Terry (2006a). "Monstrous Moonshine: The first twenty-five years". Bull. London Math. Soc. 38 (1): 1–33. arXiv:math.QA/0402345. doi:10.1112/S0024609305018217. MR 2201600..

- Gannon, Terry (2006b), Moonshine beyond the Monster: The Bridge Connecting Algebra, Modular Forms and Physics, ISBN 978-0-521-83531-2.

- Harada, Koichiro (1999), Monster Iwanami Pub., (The first book about the Monster Group written in Japanese), Iwanami Pub, ISBN 4-00-006055-4 (The first book about the Monster Group written in Japanese).

- Harada, Koichiro (2010), 'Moonshine' of Finite Groups, European Mathematical Society, ISBN 978-3-03719-090-6, MR 2722318

- Jurisich, E.; Lepowsky, J.; Wilson, R.L. (1995). "Realizations of the Monster Lie Algebra". Selecta Math. New Series. 1: 129–161. arXiv:hep-th/9408037. doi:10.1007/bf01614075.

- Jurisich, Elizabeth (1998). "Generalized Kac–Moody Lie algebras, free Lie algebras, and the structure of the Monster Lie algebra". Jour. Pure and Appl. Algebra. 126 (1–3): 233–266. arXiv:1311.3258. doi:10.1016/s0022-4049(96)00142-9.

- Li, Wei; Song, Wei; Strominger, Andrew (21 July 2008), "Chiral gravity in three dimensions", Journal of High Energy Physics, 2008 (4): 082, arXiv:0801.4566, Bibcode:2008JHEP...04..082L, doi:10.1088/1126-6708/2008/04/082.

- Maloney, Alexander; Song, Wei; Strominger, Andrew (2010), "Chiral gravity, log gravity, and extremal CFT", Phys. Rev. D, 81 (6): 064007, arXiv:0903.4573, Bibcode:2010PhRvD..81f4007M, doi:10.1103/physrevd.81.064007.

- Maloney, Alexander; Witten, Edward (2010), "Quantum Gravity Partition Functions In Three Dimensions", J. High Energy Phys., 2010 (2): 29, arXiv:0712.0155, Bibcode:2010JHEP...02..029M, doi:10.1007/JHEP02(2010)029, MR 2672754.

- Ogg, Andrew P. (1974), "Automorphismes de courbes modulaires" (PDF), Seminaire Delange-Pisot-Poitou. Theorie des nombres, tome 16, no. 1 (1974–1975), exp. no. 7 (in French), MR 0417184.

- Roberts, Siobhan (2009), King of Infinite Space: Donald Coxeter, the Man Who Saved Geometry, Bloomsbury Publishing USA, p. 361, ISBN 978-080271832-7.

- Ronan, Mark (2006), Symmetry and the Monster, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-280723-6 (Concise introduction for the lay reader).

- Ryba, A. J. E. (1996), "Modular Moonshine?", in Mason, Geoffrey; Dong, Chongying (eds.), Moonshine, the Monster, and related topics, Contemporary Mathematics, 193, Providence, RI: American Mathematical Society, pp. 307–336

- Witten, Edward (22 June 2007), Three-Dimensional Gravity Revisited, arXiv:0706.3359, Bibcode:2007arXiv0706.3359W.

External links

- Moonshine Bibliography at the Wayback Machine (archived December 5, 2006)