Name of Estonia

The name of Estonia (Estonian: Eesti [ˈeːsʲti] (![]() listen)) has complicated origins. It has been connected to Aesti, first mentioned by Tacitus around 98 AD. The name's modern geographical meaning comes from Eistland, Estia and Hestia in the medieval Scandinavian sources. Estonians adopted it as endonym in the mid-19th century, previously referring themselves generally as maarahvas, meaning "land people" or "country folk".

listen)) has complicated origins. It has been connected to Aesti, first mentioned by Tacitus around 98 AD. The name's modern geographical meaning comes from Eistland, Estia and Hestia in the medieval Scandinavian sources. Estonians adopted it as endonym in the mid-19th century, previously referring themselves generally as maarahvas, meaning "land people" or "country folk".

Etymology

Origins

The name has a colourful history, but there is no consensus on which places and peoples it has referred to at different periods.[1] Roman historian Tacitus in his Germania (ca. 98 AD), mentioned Aestiorum gentes "Aestian tribes", and some historians believe that he was directly referring to Balts while others have proposed that the name applied to the whole Eastern Baltic.[2] The word Aesti mentioned by Tacitus might derive from Latin Aestuarii meaning "Estuary Dwellers".[3] Later geographically vague mentions include Aesti by Jordanes from the 6th century and Aisti by Einhard from the early 7th century. The last mention generally considered to be applying primarily to the southern parts of the Eastern-Baltic is Eastlanda in a description of Wulfstan’s travels from the 9th century.[4] In the following centuries, views of the Eastern Baltic became more complex, and in the 11th century, Adam of Bremen mentions three islands, with Aestland being the northernmost.[5]

The Scandinavian sagas referring to Eistland were the earliest sources to use the name in its modern meaning.[6] The sagas were composed in the 13th century on the basis of earlier oral tradition by historians like Snorri Sturluson. Estonia appears as Aistland in Gutasaga and as Eistland in Ynglinga saga, Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar, Haralds saga hárfagra, and Örvar-Odds saga.[7] In Sweden, the Frugården runestone from the 11th century mentions Estlatum "Estonian lands". The first mostly reliable chronicle data comes from Gesta Danorum by the 12th century historian Saxo Grammaticus, referring to Estonia as Hestia, Estia and its people as Estonum.[8][9] The toponym Estland/Eistland has been connected to Old Norse eist, austr meaning "the east".[10] The 12th century Arab geographer al-Idrisi from Sicily, who presumably had help of some informant at Jutland in Denmark, describes Astalānda, probably referring to Estonia and the Livonian regions of Latvia.[11] From Scandinavian the name spread to German and later, following the rise of the Catholic Church, reached Latin, with Henry of Latvia in his Heinrici Cronicon Lyvoniae (ca. 1229 AD) naming the region Estonia and its inhabitants Estones.[12][13]

Adoption by Estonians

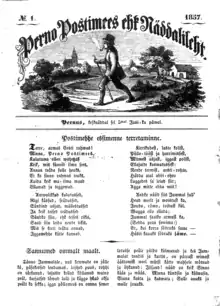

The endonym maarahvas, literally meaning "land people" or "country folk", was used up until the mid-19th century.[14] Its origins are unclear; there is a hypothesis of it originating from the prehistoric period, but no supporting evidence has been found. Another proposed explanation relates to its being a medieval loan-translation from German Landvolk.[13][14][15] Although the name had been used earlier, Johann Voldemar Jannsen played a major role in popularisation of Eesti rahvas "Estonian people" among the Estonians themselves, during the Estonian national awakening.[16] The first number of his newspaper Perno Postimees in 1857 started with "Terre, armas Eesti rahwas!" meaning "Hello, dear Estonian people!".[17]

In other languages

Esthonia was a common alternative English spelling. In 1922, in response to a letter by Estonian diplomat Oskar Kallas raising the issue, the Royal Geographical Society agreed that the correct spelling was Estonia. Formal adoption took place at the government level only in 1926, with the United Kingdom and United States then adopting the spelling Estonia. In the same year this spelling was officially endorsed by the Estonian government, alongside Estonie in French, and Estland in German, Danish, Dutch, Norwegian, and Swedish.[18]

In Finnish Estonia is known as Viro, originating from the historic independent county Virumaa. In a similar vein, the corresponding Latvian word Igaunija derives from Ugandi County.[19]

References

- Kasik 2011, p. 11

- Mägi 2018, pp. 144-145

- Theroux 2011, p. 22

- Mägi 2018, pp. 145-146

- Mägi 2018, p. 148

- Tvauri 2012, p. 31

- Tvauri 2012, pp. 29-31

- Tvauri 2012, pp. 31-32

- Kasik 2011, p. 12

- Mägi 2018, p. 144

- Mägi 2018, p. 151

- Rätsep 2007, p. 11

- Tamm, Kaljundi & Jensen 2016, pp. 94-96

- Beyer 2011, pp. 12-13

- Paatsi 2012, pp. 2-3

- Paatsi 2012, pp. 20-21

- Paatsi 2012, p. 1

- Loit 2008, pp. 144-146

- Theroux 2011, p. 22

Bibliography

- Beyer, Jürgen (2011). "Are Folklorists Studying the Tales of the Folk?" (PDF). Folklore. Taylor & Francis. 122 (1). doi:10.1080/0015587X.2011.537132. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Loit, Aleksander (2008). "Esthonia – Estonia?". Tuna (in Estonian). 38 (1). ISSN 1406-4030. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Mägi, Marika (2018). In Austrvegr: The Role of the Eastern Baltic in Viking Age Communication across the Baltic Sea. BRILL. ISBN 9789004363816.

- Kasik, Reet (2011). Stahli mantlipärijad. Eesti keele uurimise lugu (in Estonian). Tartu University Press. ISBN 9789949196326.

- Paatsi, Vello (2012). ""Terre, armas eesti rahwas!": Kuidas maarahvast ja maakeelest sai eesti rahvas, eestlased ja eesti keel". Akadeemia (in Estonian). 24 (2). ISSN 0235-7771. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Rätsep, Huno (2007). "Kui kaua me oleme olnud eestlased?" (PDF). Oma Keel (in Estonian). 14. Retrieved 21 January 2020.

- Tamm, Marek; Kaljundi, Linda; Jensen, Carsten Selch (2016). Crusading and Chronicle Writing on the Medieval Baltic Frontier: A Companion to the Chronicle of Henry of Livonia. Routledge. ISBN 9781317156796.

- Theroux, Alexander (2011). Estonia: A Ramble Through the Periphery. Fantagraphics Books. ISBN 9781606994658.

- Tvauri, Andres (2012). Laneman, Margot (ed.). The Migration Period, Pre-Viking Age, and Viking Age in Estonia. Tartu University Press. ISBN 9789949199365. ISSN 1736-3810. Retrieved 21 January 2020.