Naraka (Jainism)

Naraka (Sanskrit: नरक) is the realm of existence in Jain cosmology characterized by great suffering. Naraka is usually translated into English as "hell" or "purgatory".

| Part of a series on |

| Jainism |

|---|

|

|

|

Naraka differs from the hells of Abrahamic religions as souls are not sent to Naraka as the result of a divine judgment and punishment. Furthermore, the length of a being's stay in a Naraka is not eternal, though it is usually very long—measured in billions of years. A soul is reborn into a Naraka as a direct result of his or her previous karma (actions of body, speech and mind), and resides there for a finite length of time until his karma has achieved its full result. After his karma is used up, he may be reborn in one of the higher worlds as the result of an earlier karma that had not yet ripened.

Types of hells

These realms are situated in the seven lower levels (adho lok) of the universe while the human abode of Jambudvip is in the middle (madhya lok) and the heavenly realms exist above (urdhva loka). These layers together, form the shape of a man with arms akimbo (the familiar 'keyhole' shaped emblem of Jainism), with the human realm of Jambudvip at the waist, adho lok below, urdhva lok above, and siddha lok or siddhashila (the realm of the siddhas) at or above the head. Many Jain temples are built to display this cosmology such Jambudvip in Hastinapur and the fifteen story Trilok Teerth Dham temple in Uttar Pradesh. The seven lower grounds are:

- Ratna prabha.

- Sharkara prabha.

- Valuka prabha.

- Panka prabha.

- Dhuma prabha.

- Tamaha prabha.

- Mahatamaha prabha.

The first ground, owing to a predominance of ratnas or jewels, is called Ratnaprabha. Similarly, the second, owing to a predominance of sarkara or gravel, is called Sarkraprabha. The third owing to a predominance of valuka or sands, is called Valukaprabha. The fourth, owing to an excess of panka or mud, is called Pankaprabha. The fifth, owing to an excess of dhuma or smoke, is called Dhumaprabha. The sixth, owing to a marked possession of tamas or darkness, is called Tamahprabha, while the seventh, owing to a high concentration of mahatamas or dense darkness, is called Mahatamahprabha.[1]

Hellish beings

The hellish beings (Sanskrit: नारकीय, Nārakī) are a type of soul which reside in these various hells. They are born in hells by sudden manifestation.[2] The hellish beings each possess a vaikriya body (protean body which can transform itself and take various forms). They have a fixed life span in the respective hells where they reside. The minimum life span of hellish beings in the first to seventh hellish grounds is 10000 years, 1 sagaropama year (Ocean-measured years which are countless years as per Jain cosmology),[note 1] 3 sagaropama years, 7 sagaropama years, 10 sagaropama years, 17 sagaropama years and 22 sagaropama years respectively. The maximum life span of hellish beings in the first to sixth hellish grounds is 1 sagaropama year, 3 sagaropama years, 7 sagaropama years, 10 sagaropama years, 17 sagaropama years and 22 sagaropama years respectively. They experience five types of sufferings: bodily pain, inauspicious leśyā or soul colouring and pariṇāma or physical transformation, from the nature and location of hells, pain inflicted on one other and torture inflicted by mansion-dwelling demi-gods.

Causes of birth in Hell

In a dialogue between Sudharma Swami and Mahavira in the Jain text Sutrakritanga, Mahavira speaks of various reasons a soul may take birth in hells:[3]

- Sudharma Swami: What is the punishment in the hells? Knowing it, O sage, tell it me who do not know it! How do sinners go to hell?

- Mahavira: I shall describe the truly insupportable pains where there is distress and (the punishment of) evil deeds. Those cruel sinners who, from a desire of (worldly) life, commit bad deeds, will sink into the dreadful hell which is full of dense darkness and great suffering. He who always kills movable and immovable beings for the sake of his own comfort, who injures them, who takes what is not freely given, who does not learn what is to be practised (viz. control). The impudent sinner, who injures many beings without relenting will go to hell; at the end of his life he will sink to the (place of) darkness; head downwards he comes to the place of torture. The prisoners in hell lose their senses from fright, and do not know in what direction to run. Going to a place like a burning heap of coals on fire, and being burnt they cry horribly; they remain there long, shrieking aloud.

According to Jain scripture, Tattvarthasutra, following are the causes for birth in hell:[4]

- Killing or causing pain with intense passion.

- Excessive attachment to things and worldly pleasure with constantly indulging in cruel and violent acts.

- Vowless and unrestrained life.[5]

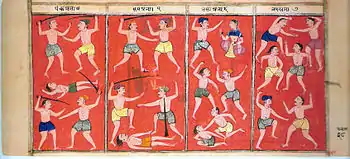

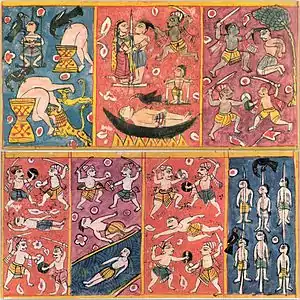

Description of tortures of hell

In a dialogue between Sudharma and Mahavira the Jain text Sutrakritanga, Mahavira describes various tortures and sufferings in hells:[6]

- They cross the horrible Vaitarani, being urged on by arrows, and wounded with spears. The punishers pierce them with darts; they go in the boat, losing their memory; others pierce them with long pikes and tridents, and throw them on the ground. Some, round whose neck big stones are tied, are drowned in deep water. Others again roll about in the Kadambavâlukâ (river) or in burning chaff, and are roasted in it. And they come to the great impassable hell, full of agony, called Asûrya (i.e. where the sun does not shine), where there is great darkness, where fires, placed above, below, and all around, are blazing. There, as in a cave, being roasted on the fire, he is burned, having lost the reminiscence (of his sins) and consciousness of everything else; always suffering (he comes) to that miserable hot place that is ever ready (for the punishment of evildoers) There the cruel punishers have lighted four fires, and roast the sinners; they are roasted there like fishes put on the fire alive.

- The prisoners in hell come to the dreadful place called Santakshana (i.e. cutting), where the cruel punishers tie their hands and feet, and with axes in their hands cut them like wooden planks. And they turn the writhing victims round, and stew them, like living fishes, in an iron caldron filled with their own blood, their limbs covered with ordure, their heads smashed.

In Hell beings have a life span of innumerable years and are not easily killed even though they endure great torture. Even if they are killed they immediately take birth and are then repeatedly killed. This is described as thus:

- They are not reduced to ashes there, and they do not die of their enormous pains; undergoing this punishment, the miserable men suffer for their misdeeds. And there in the place, where there is constant shivering, they resort to a large burning fire; but they find no relief in that place of torture; the tormentors torture them still. There is heard everywhere the noise of painfully uttered cries even as in the street of a town. Those whose bad Karman takes effect (viz. the punishers), violently torment again and again those whose bad Karman takes effect also (viz. the punished).

- They deprive the sinner of his life; I shall truly tell you how this is done. The wicked (punishers) remind by (similar) punishment (their victims) of all sins they had committed in a former life. Being killed they are thrown into a hell which is full of boiling filth. There they stay eating filth, and they are eaten by vermin. And there is an always crowded, hot place, which men deserve for their great sins, and which is full of misery. (The punishers) put them in shackles, beat their bodies, and torment them (by perforating) their skulls with drills. They cut off the sinner's nose with a razor, they cut off both his ears and lips; they pull out his tongue a span's length and torment (him by piercing it) with sharp pikes. There the sinners dripping (with blood) whine day and night even as the dry leaves of a palm-tree (agitated by the wind). Their blood, matter, and flesh are dropping off while they are roasted, their bodies being besmeared with natron. Have you heard of the large, erected caldron of more than man's size, full of blood and matter, which is extremely heated by a fresh fire, in which blood and matter are boiling? The sinners are thrown into it and boiled there, while they utter horrid cries of 'Agony; they are made to drink molten lead and copper when they are thirsty, and they shriek still more horribly. Those evildoers who have here forfeited their souls' (happiness) for the sake of small (pleasures), and have been born in the lowest births during hundred thousands of million years will stay in this (hell). Their punishment will be adequate to their deeds. The wicked who have committed crimes will atone for them, deprived of all pleasant and lovely objects, by dwelling in the stinking crowded hell, a scene of pain, which is full of flesh.

Notes

- As per the Jain cosmology Sirsapahelika is the highest measurable number in Jainism which is 10^194 years. Higher than that is palyopama (pit measured years) which is explained by an analogy of a pit. Accordingly, a hollow pit of 8 x 8 x 8 miles tightly filled with hair particles of seven day old newly born. [A single hair from the above cut into eight pieces seven times = 2,097,152 Particles]. 1 Particle emptied after every 100 years, the time taken to empty the whole pit = 1 Palyopama. (1 Palyopama = countless years.) Hence palyopama is at least greater than 10^194 years. Sagrapoma is 10 Quadrillion Palyopama, that means a Sagrapoma is more than 10^210 Years

References

- Sanghvi, Sukhlal (1974). Commentary on Tattvārthasūtra of Vācaka Umāsvāti. trans. by K. K. Dixit. Ahmedabad: L. D. Institute of Indology. pp. 133–134.

- Sanghvi, Sukhlal (1974). Commentary on Tattvārthasūtra of Vācaka Umāsvāti. trans. by K. K. Dixit. Ahmedabad: L. D. Institute of Indology. pp. 107

- Jacobi, Hermann (1895). F. Max Müller (ed.). The Sūtrakritanga. Sacred Books of the East vol.45, Part 2. Oxford: The Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-7007-1538-X. verse SK:5.1.1-6

- Sanghvi, Sukhlal (1974) pp.250-52

- refer Mahavrata for the vows and restraints in Jainism

- Jacobi 1895, p. verse SK:5.1.8-27.

Sources

- Jacobi, Hermann (1895), F. Max Müller (ed.), The Sūtrakritanga, Sacred Books of the East vol.45, Part 2, Oxford: The Clarendon Press, ISBN 0-7007-1538-X