National Bolshevism

National Bolshevism (Russian: Национал-большевизм, German: Nationalbolschewismus), whose supporters are known as National Bolsheviks (Russian: Национал-большевики), NatBols or NazBols (Russian: Нацболы),[1] is a political movement that combines elements of fascism and Bolshevism.[2][3]

| Part of the Politics and elections and Politics series on |

| Neo-fascism |

|---|

|

|

Notable proponents of National Bolshevism in Germany included Ernst Niekisch (1889–1967), Heinrich Laufenberg (1872–1932), and Karl Otto Paetel (1906–1975). In Russia, Nikolay Ustryalov (1890–1937) and his followers, the Smenovekhovtsy used the term.

Notable modern advocates of the movement include Aleksandr Dugin and Eduard Limonov, who led the unregistered and banned National Bolshevik Party (NBP) in the Russian Federation[4] as well as the Nazbol Party of the USNR.

German National Bolshevism

National Bolshevism as a term was first used to describe a current in the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) and then the Communist Workers' Party of Germany (KAPD) which wanted to ally the insurgent communist movement with dissident nationalist groups in the German army who rejected the Treaty of Versailles.[5] They were led by Heinrich Laufenberg and Fritz Wolffheim and were based in Hamburg. Their expulsion from the KAPD was one of the conditions that Karl Radek explained was necessary if the KAPD was to be welcomed to the Third Congress of the Third International. However, the demand that they withdraw from the KAPD would probably have happened anyway. Radek had dismissed the pair as National Bolsheviks, the first recorded use of the term in a German context.[6]

Radek subsequently courted some of the radical nationalists he had met in prison to unite with the Bolsheviks in the name of National Bolshevism. He saw in a revival of National Bolshevism a way to "remove the capitalist isolation" of the Soviet Union.[2]

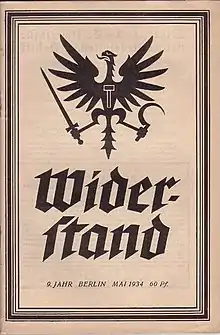

During the 1920s, a number of German intellectuals began a dialogue which created a synthesis between radical nationalism (typically referencing Prussianism) and Bolshevism as it existed in the Soviet Union. The main figure in this was Ernst Niekisch of the Old Social Democratic Party of Germany, who edited the Widerstand journal.[7]

A National Bolshevik tendency also existed with the German Youth Movement, led by Karl Otto Paetel. Paetel had been a supporter of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), but became disillusioned with them as he did not feel they were truly committed to revolutionary activity or socialist economics. His 1930-formed movement, the Group of Social Revolutionary Nationalists, sought to forge a third way between the NSDAP and the KPD, emphasising both nationalism and socialist economics.[8] He was especially active in a largely unsuccessful attempt to win over a section of the Hitler Youth to his cause.[9]

Although members of the NSDAP under Adolf Hitler did not take part in Niekisch's National Bolshevik project and usually presented Bolshevism in exclusively negative terms as a Jewish conspiracy, in the early 1930s there was a parallel tendency within the NSDAP which advocated similar views. This was represented by what has come to be known as Strasserism. A group led by Hermann Ehrhardt, Otto Strasser and Walther Stennes broke away in 1930 to found the Combat League of Revolutionary National Socialists, commonly known as the Black Front.[10]

After the Second World War, the Socialist Reich Party was established, which combined neo-Nazi ideology with a foreign policy critical of the United States and supportive of the Soviet Union, which funded the party.[11][12]

Russian National Bolshevism

Russian Civil War

As the Russian Civil War dragged on, a number of prominent Whites switched to the Bolshevik side because they saw it as the only hope for restoring greatness to Russia. Amongst these was Professor Nikolai Ustrialov, initially an anti-communist, who came to believe that Bolshevism could be modified to serve nationalistic purposes. His followers, the Smenovekhovtsy (named after a series of articles he published in 1921) Smena vekh (Russian: change of milestones), came to regard themselves as National Bolsheviks, borrowing the term from Niekisch.[13]

Similar ideas were expressed by the Evraziitsi party and the pro-monarchist Mladorossi. Joseph Stalin's idea of socialism in one country was interpreted as a victory by the National Bolsheviks.[13] Vladimir Lenin, who did not use the term National Bolshevism, identified the Smenovekhovtsy as a tendency of the old Constitutional Democratic Party who saw Russian communism as just an evolution in the process of Russian aggrandisement. He further added that they were a class enemy and warned against communists believing them to be allies.[14]

Co-option of National Bolshevism

Ustrialov and others sympathetic to the Smenovekhovtsy cause, such as Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy and Ilya Ehrenburg, were eventually able to return to the Soviet Union and following the co-option of aspects of nationalism by Stalin and his ideologue Andrei Zhdanov enjoyed membership of the intellectual elite under the designation non-party Bolsheviks.[15][16] Similarly. B. D. Grekov's National Bolshevik school of historiography, a frequent target under Lenin, was officially recognised and even promoted under Stalin, albeit after accepting the main tenets of Stalinism.[17] Indeed, it has been argued that National Bolshevism was the main impetus for the revival of patriotism as an official part of state ideology in the 1930s.[18][19]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn vs. Eduard Limonov

The term National Bolshevism has sometimes been applied to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and his brand of anti-communism.[20] However, Geoffrey Hosking argues in his History of the Soviet Union that Solzhenitsyn cannot be labelled a National Bolshevik since he was thoroughly anti-Stalinist and wished a revival of Russian culture that would see a greater role for the Russian Orthodox Church, a withdrawal of Russia from its role overseas and a state of international isolationism.[20] Solzhenitsyn and his followers, known as vozrozhdentsy (revivalists), differed from the National Bolsheviks, who were not religious in tone (although not completely hostile to religion) and who felt that involvement overseas was important for the prestige and power of Russia.[20]

There was open hostility between Solzhenitsyn and Eduard Limonov, the head of Russia's unregistered National Bolshevik Party. Solzhenitsyn had described Limonov as "a little insect who writes pornography" and Limonov described Solzhenitsyn as a traitor to his homeland who contributed to the downfall of the Soviet Union. In The Oak and the Calf, Solzhenitsyn openly attacked the notions that the Russians were "the noblest in the world" and that "tsarism and Bolshevism [...] [were] equally irreproachable", defining this as the core of the National Bolshevism to which he was opposed.[21]

National Bolshevik Party

The current National Bolshevik Party (NBP) was founded in 1992 as the National Bolshevik Front, an amalgamation of six minor groups.[23] The party has always been led by Eduard Limonov. Limonov and Dugin sought to unite far-left and far-right radicals on the same platform.[24] With Dugin viewing national-bolsheviks as a point between communist and fascists, and forced to act in the peripheries of each group. The group's early policies and actions show some alignment and sympathy with radical nationalist groups, albeit while still holding to the tenets of a form of Marxism that Dugin defined as "Marx minus Feuerbach, i. e. minus evolutionism and sometimes appearing inertial humanism.", but a split occurred in the 2000s which changed this to an extent. This led to the party moving further left in Russia's political spectrum, and lead to members of the party denouncing Dugin and his group as fascists.[25] Dugin subsequently developed close ties to the Kremlin and served as an adviser to senior Russian official Sergey Naryshkin.[26][27]

Initially opposed to Vladimir Putin, Limonov at first somewhat liberalized the NBP and joined forces with leftist and liberal groups in Garry Kasparov's United Civil Front to fight Putin.[28] However, he later expressed more supportive views of Putin following the 2014 pro-Russian unrest in Ukraine.[29][30][31]

Other countries

The Franco-Belgian Parti Communautaire National-Européen shares National Bolshevism's desire for the creation of a united Europe as well as many of the NBP's economic ideas. French political figure Christian Bouchet has also been influenced by the idea.[32]

In 1944, Indian nationalist leader Subhas Chandra Bose called for "a synthesis between National Socialism and communism" to take root in India.[33]

That same year, the new leadership of the Israeli paramilitary organization Lehi declared its support for National Bolshevism, a break from the group's fascist outlook under its previous leader Avraham Stern.[34]

Some have described the Serbian Radical Party, the Bulgarian Attack party, the Slovenian National Party and the Greater Romania Party as "National Bolshevik" for blending much of their respective countries' far-right rhetoric with traditional left-wing stances such as socialised economies, anti-imperialism and defense of historical communist rule. The Serbian Radical Party in particular has given support to leaders such as Muammar Gaddafi,[35] Saddam Hussein[36] and current Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro.[37] The Greater Romania Party on the other hand was founded by Corneliu Vadim Tudor, described as the "Court Poet of Nicolae Ceaușescu",[38] and has been seen as a continuation of the latter's ideology with a right-wing veneer.

See also

- Black Front

- Eurasia Party

- Fascism

- The Fourth Political Theory, a book by Aleksandr Dugin

- Juche

- Marxism–Leninism

- National Bolshevik Front

- Nazi-Maoism

- Neo-socialism

- Neo-Sovietism

- Neo-Stalinism

- Nouvelle Droite

- Radical centrism

- Revisionism (Marxism)

- Right-wing socialism

- Russian nationalism

- Sankarism

- Strasserism

- Syncretic politics

- Third International Theory

- Third Position

- Titoism

Footnotes

- Russian Nationalism, Foreign Policy and Identity Debates in Putin's Russia: New Ideological Patterns after the Orange Revolution. Columbia University Press. 2014. p. 147. ISBN 9783838263250. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- Von Klemperer, Klemens (1951). "Towards a Fourth Reich? The History of National Bolshevism in Germany". Review of Politics. 13 (2): 191–210. doi:10.1017/S0034670500047422. JSTOR 1404764.

- Van Ree, Erik (4 August 2010). "The concept of 'National Bolshevism': An interpretative essay" (PDF). Journal of Political Ideologies. 6 (3): 289–307. doi:10.1080/13569310120083017. S2CID 216092681.

- "Court Upholds Registration Ban Against National Bolshevik Party"

- Pierre Broué, Ian Birchall, Eric D. Weitz, John Archer, The German Revolution, 1917–1923, Haymarket Books, 2006, pp. 325–326.

- Timothy S. Brown, Weimar Radicals: Nazis and Communists Between Authenticity and Performance, Berghahn Books, 2009, p. 95.

- Martin A. Lee, The Beast Reawakens, Warner Books, 1998, p. 315.

- Brown, Weimar Radicals, pp. 31-32

- Brown, Weimar Radicals, p. 134.

- Robert Lewis Koehl, The SS: A History 1919–1945, Tempus Publishing, 2004, pp. 61–63.

- T. H. Tetens, The New Germany and the Old Nazis (London: Secker & Warburg, 1962), p. 78.

- "Encyclopedia of modern worldwide extremists and extremist groups", Stephen E. Atkins. Greenwood Publishing Group, 2004. ISBN 0-313-32485-9, ISBN 978-0-313-32485-7. pp. 273-274

- Lee, The Beast Reawakens, p. 316.

- Speech by Vladimir Lenin on 27 March 1922 in V. Lenin, On the Intelligentsia, Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1983, pp. 296–299.

- S. V. Utechin, Russian Political Thought: A Concise and Comprehensive History, JM Dent & Sons, 1964, pp. 254–255

- Krausz, Tamas (3 April 2008). "National bolshevism ‐ past and present". Contemporary Politics. 1 (2): 114–120. doi:10.1080/13569779508449884.

- Utechin, Russian Political Thought, p. 255.

- Utechin, Russian Political Thought, p. 241.

- Brandenberger, David (2002). National Bolshevism: Stalinist Mass Culture and the Formation of Modern Russian National Identity, 1931-1956. Bookshelf. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674009066.

- G. Hosking, A History of the Soviet Union, London: Fontana, 1990, pp. 421–2

- A. Solzhenitsyn, The Oak and the Calf, 1975, pp. 119–129.

- A. Dugin. "Fascism is limitless and red"

- M. A. Lee, The Beast Reawakens, 1997, p. 314.

- Rogatchevski, Andrei; Steinholt, Yngvar (21 October 2015). "Pussy Riot's Musical Precursors? The National Bolshevik Party Bands, 1994–2007". Popular Music and Society. 39 (4): 448–464. doi:10.1080/03007766.2015.1088287. S2CID 192339798.

- Yasmann, Victor (29 April 2005). "Russia: National Bolsheviks, The Party Of 'Direct Action'". Radio Free Europe Radio Liberty. Retrieved 15 November 2018.

For this mobilization, the NBP used a bizarre mixture of totalitarian and fascist symbols, geopolitical dogma, leftist ideas, and national-patriotic demagoguery.

- John Dunlop (January 2004). "Aleksandr Dugin's Foundations of Geopolitics". Demokratizatsiya. 12 (1): 41. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014.

- Shaun Walker (23 March 2014). "Ukraine and Crimea: what is Putin thinking?". The Guardian.

- Remnick, David (1 October 2007). "The Tsar's Opponent". The New Yorker. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- Kravtsova, Yekaterina (10 March 2014). "Ukraine crisis: Crimea is just the first step, say Moscow's pro-Putin demonstrators". Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- "Famous Kremlin Critic Changes Course, Says Putin Not a Monster (Limonov)". 12 October 2015. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Bershidsky, Leonid (30 December 2014). "Putin Goes Medieval on the Russian Opposition". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2 December 2016 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- G. Atkinson (August 2002). "Nazi shooter targets Chirac". Searchlight.

- Shanker Kapoor, Ravi (2017), "There is No Such Thing As Hate Speech", Bloomsbury Publishing

- Robert S. Wistrich, David Ohana. The Shaping of Israeli Identity: Myth, Memory, and Trauma, Issue 3. London, England, UK; Portland, Oregon, USA: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd., 1995. Pp. 88.

- "SRS holds rally in support of Gaddafi". B92.net. 10 April 2011. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

- http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/01/24/AR2007012401340.html

- (21 February 2019) "Venezuela strengthens relations of solidarity and cooperation with the Republic of Serbia"

- "Corneliu Vadim Tudor: Court poet to Nicolae Ceausescu who became an extreme nationalist figure after the fall of communism in Romania". The Independent. 17 September 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National Bolshevism. |