Far-right politics

Far-right politics, also referred to as the extreme right or right-wing extremism, are politics further on the right of the left–right political spectrum than the standard political right, particularly in terms of anti-communist, authoritarian, ultranationalist, and nativist ideologies and tendencies.[1]

| Part of the Politics series | ||||||

| Party politics | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) | ||||||

| Political spectrum | ||||||

|

||||||

| Party platform | ||||||

| Party organization | ||||||

| Party Leadership | ||||||

|

||||||

| Party system | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Coalition | ||||||

|

|

||||||

| Lists | ||||||

|

| ||||||

Historically used to describe the experiences of fascism and Nazism, today far-right politics includes neo-fascism, neo-Nazism, the Third Position, the alt-right, racial supremacism, and other ideologies or organizations that feature aspects of ultranationalist, chauvinist, xenophobic, theocratic, racist, homophobic, transphobic, or reactionary views.[2]

Far-right politics can lead to oppression, political violence, forced assimilation, ethnic cleansing, and genocide against groups of people based on their supposed inferiority, or their perceived threat to the native ethnic group, nation, state, national religion, dominant culture, or ultraconservative traditional social institutions.[3]

Overview

Concept and worldview

The core of the far right's worldview is organicism, the idea that society functions as a complete, organized and homogeneous living being. Adapted to the community they wish to constitute or reconstitute (whether based on ethnicity, nationality, religion or race), the concept leads them to reject every form of universalism in favor of autophilia and alterophobia, or in other words the idealization of a "we" excluding a "they".[4] The far right tends to absolutize differences between nations, races, individuals or cultures since they disrupt their efforts towards the utopian dream of the "closed" and naturally organized society, perceived as the condition to ensure the rebirth of a community finally reconnected to its quasi-eternal nature and re-established on firm metaphysical foundations.[5][6]

As they view their community in a state of decay facilitated by the ruling elites, far-right members portray themselves as a natural, sane and alternative elite, with the redemptive mission of saving society from its promised doom. They reject both their national political system and the global geopolitical order (including their institutions and values, e.g. political liberalism and egalitarian humanism) which are presented as needing to be abandoned or purged of their impurities, so that the "redemptive community" can eventually leave the current phase of liminal crisis to usher in the new era.[4][6] The community itself is idealized through great archetypal figures (the Golden Age, the savior, decadence and global conspiracy theories) as they glorify irrationalistic and non-materialistic values such as the youth or the cult of the dead.[4]

Political scientist Cas Mudde argues that the far right can be viewed as a combination of four broadly defined concepts, namely exclusivism (e.g. racism, xenophobia, ethnocentrism, ethnopluralism, chauvinism, or welfare chauvinism), anti-democratic and non-individualist traits (e.g. cult of personality, hierarchism, monism, populism, anti-particracy, an organicist view of the state), a traditionalist value system lamenting the disappearance of historic frames of reference (e.g. law and order, the family, the ethnic, linguistic and religious community and nation as well as the natural environment) and a socioeconomic program associating corporatism, state control of certain sectors, agrarianism and a varying degree of belief in the free play of socially Darwinistic market forces. Mudde then proposes a subdivision of the far-right nebula into moderate and radical leanings, according to their degree of exclusionism and essentialism.[7][8]

Definition and comparative analysis

The Encyclopedia of Politics: The Left and the Right states far-right politics include "persons or groups who hold extreme nationalist, xenophobic, racist, religious fundamentalist, or other reactionary views." While the term far right is typically applied to fascists and neo-Nazis, it has also been used to refer to these to the right of mainstream right-wing politics.[9]

According to political scientist Lubomír Kopeček, "[t]he best working definition of the contemporary far right may be the four-element combination of nationalism, xenophobia, law and order, and welfare chauvinism proposed for the Western European environment by Cas Mudde."[10] Relying on those concepts, far-right politics includes yet is not limited to aspects of authoritarianism, anti-communism[10] and nativism.[11] Claims that superior people should have greater rights than inferior people are often associated with the far right, as they have historically favored a social Darwinistic or elitist hierarchy based on the belief in the legitimacy of the rule of a supposed superior minority over the inferior masses.[12] Regarding the socio-cultural dimension of nationality, culture and migration, one far-right position is the view that certain ethnic, racial or religious groups should stay separate, based on the belief that the interests of one's own group should be prioritized.[13]

According to Kopeček, in comparing the Western European and post-Communist Central European far-right, "[t]he Central European far right was also typified by a strong anti-Communism, much more markedly than in Western Europe", allowing for "a basic ideological classification within a unified party family, despite the heterogeneity of the far right parties." Kopeček concludes that a comparison of Central European far-right parties with those of Western Europe shows that "these four elements are present in Central Europe as well, though in a somewhat modified form, despite differing political, economic, and social influences."[10]

In the American and more general Anglo-Saxon environment, the most common term is radical right. Kopeček writes that "it has a much broader and different meaning than in the German environment. It is influenced by the older tradition of American nativism (anti-immigration sentiment), populism, and hostility to central government combined with ultra-nationalism, anti-communism, Christian Fundamentalism, and militaristic orientation."[10] Jodi Dean argues that "the rise of far-right anti-communism in many parts of the world" should be interpreted "as a politics of fear, which utilizes the disaffection and anger generated by capitalism. [...] Partisans of far right-wing organizations, in turn, use anti-communism to challenge every political current which is not embedded in a clearly exposed nationalist and racist agenda. For them, both the USSR and the European Union, leftist liberals, ecologists, and supranational corporations – all of these may be called 'communist' for the sake of their expediency."[14]

Modern debates

Terminology

According to Jean-Yves Camus and Nicolas Lebourg, the modern ambiguities in the definition of far-right politics lie in the fact that the concept is generally used by political adversaries to "disqualify and stigmatize all forms of partisan nationalism by reducing them to the historical experiments of Italian Fascism [and] German National Socialism."[15] While the existence of such a political position is widely accepted among scholars, figures associated with the far-right rarely accept this denomination, preferring terms like "national movement" or "national right".[16] There is also debate about how appropriate the labels neo-fascist or neo-Nazi are. In the words of Mudde, "the labels Neo-Nazi and to a lesser extent neo-Fascism are now used exclusively for parties and groups that explicitly state a desire to restore the Third Reich or quote historical National Socialism as their ideological influence."[17]

One issue is whether parties should be labelled radical or extreme, a distinction that is made by the Federal Constitutional Court of Germany when determining whether or not a party should be banned. An extremist party opposes liberal democracy and the constitutional order while a radical one accepts free elections and the parliament as legitimate structures.[nb 1] After a survey of the academic literature, Mudde concluded in 2002 that the terms "right-wing extremism", "right-wing populism", "national populism", or "neo-populism" were often used as synonyms by scholars, in any case with "striking similarities", except notably among a few authors studying the extremist-theoretical tradition.[nb 2] The label "radical right" is also used in the American tradition, although it has a broader meaning in the United States than in Europe.[nb 3]

Relation to right-wing politics

Another question is what the label "right" implies when it is applied to the extreme right, given the fact that many parties that were originally labeled right-wing extremist tended to advance neoliberal and free market agendas as late as the 1980s, but they now advocate economic policies which are more traditionally associated with the left such as anti-globalization, nationalization and protectionism. One approach, drawing on the writings of Norberto Bobbio, argues that attitudes towards equality are what distinguish the left from the right and they allow these parties to be positioned on the right of the political spectrum.[18]

Aspects of far-right ideology can be identified in the agenda of some contemporary right-wing parties, in particular the idea that superior persons should dominate society while undesirable elements should be purged which in extreme cases resulted in genocides.[19] Charles Grant, director of the Centre for European Reform in London, distinguishes between fascism and right-wing nationalist parties which are often described as far right such as the National Front in France.[20] Mudde notes that the most successful European far-right parties in 2019 were "former mainstream right-wing parties that have turned into populist radical right ones."[21] According to historian Mark Sedgwick, "[t]here is no general agreement as to where the mainstream ends and the extreme starts, and if there ever had been agreement on this, the recent shift in the mainstream would challenge it."[22]

Proponents of the horseshoe theory interpretation of the left–right spectrum identify the far left and the far right as having more in common with each other as extremists than each of them has with centrists or moderates.[23] However, the horseshoe theory does not enjoy support within academic circles[24] and has received criticism,[24][25][26] including the view that it has been centrists who have supported far-right and fascist regimes that they prefer in power over socialist ones.[27]

Nature of support

Jens Rydgren describes a number of theories as to why individuals support far-right political parties and the academic literature on this topic distinguishes between demand-side theories that have changed the "interests, emotions, attitudes and preferences of voters" and supply-side theories which focus on the programmes of parties, their organization and the opportunity structures within individual political systems.[28] The most common demand-side theories are the social breakdown thesis, the relative deprivation thesis, the modernization losers thesis and the ethnic competition thesis.[29]

The rise of far-right parties has also been viewed as a rejection of post-materialist values on the part of some voters. This theory which is known as the reverse post-material thesis blames both left-wing and progressive parties for embracing a post-material agenda (including feminism and environmentalism) that alienates traditional working class voters.[30][31] Another study argues that individuals who join far-right parties determine whether those parties develop into major political players or whether they remain marginalized.[32]

Early academic studies adopted psychoanalytical explanations for the far right's support. The 1933 publication The Mass Psychology of Fascism by Wilhelm Reich argued the theory that fascists came to power in Germany as a result of sexual repression. For some far-right parties in Western Europe, the issue of immigration has become the dominant issue among them, so much so that some scholars refer to these parties as "anti-immigrant" parties.[33]

Intellectual history

Background

The French Revolution in 1789 created a major shift in political thought by challenging the established ideas supporting hierarchy with new ones about universal equality and freedom.[34] The modern left–right political spectrum also emerged during this period. Democrats and proponents of universal suffrage were located on the left side of the elected French Assembly, while monarchists seated farthest to the right.[16]

The strongest opponents of liberalism and democracy during the 19th century, such as Joseph de Maistre and Friedrich Nietzsche, were highly critical of the French Revolution.[34] Those who advocated a return to the absolute monarchy during the 19th century called themselves "ultra-monarchists" and embraced a "mystic" and "providentialist" vision of the world where royal dynasties were seen as the "repositories of divine will". The opposition to liberal modernity was based on the belief that hierarchy and rootedness are more important than equality and liberty, with the latter two being dehumanizing.[35]

Emergence

In the French public debate following the Bolshevik Revolution, far right was used to describe the strongest opponents of the far left, i.e. those who supported the events occurring in Russia.[5] A number of thinkers on the far right nonetheless claimed an influence from an anti-Marxist and anti-egalitarian definition of socialism, based on a military comradeship that rejected Marxist class analysis, or what Oswald Spengler had called a "socialism of the blood", sometimes described by scholars as a form of "socialist revisionism".[36] They included Charles Maurras, Benito Mussolini, Arthur Moeller van den Bruck and Ernst Niekisch.[37][38][39] Those thinkers eventually split along nationalist lines from the original communist movement, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels contradicting nationalist theories with the idea that "the working men [had] no country."[40] The main reason for that ideological confusion can be found in the consequences of the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, which according to Swiss historian Philippe Burrin had completely redesigned the political landscape in Europe by diffusing the idea of an anti-individualistic concept of "national unity" rising above the right and left division.[39]

As the concept of "the masses" was introduced into the political debate through industrialization and the universal suffrage, a new right-wing founded on national and social ideas began to emerge, what Zeev Sternhell has called the "revolutionary right" and a foreshadowing of fascism. The rift between the left and nationalists was furthermore accentuated by the emergence of anti-militarist and anti-patriotic movements like anarchism or syndicalism, which shared even less similarities with the far right.[40] The latter began to develop a "nationalist mysticism" entirely different from that on the left, and antisemitism turned into a credo of the far right, marking a break from the traditional economic "anti-Judaism" defended by parts of the far left, in favour of a racial and pseudo-scientific notion of alterity. Various nationalist leagues began to form across Europe like the Pan-German League or the Ligue des Patriotes, with the common goal of a uniting the masses beyond social divisions.[41][42]

Völkisch and revolutionary right

_-_Fondo_Mar%C3%ADn-Kutxa_Fototeka.jpg.webp)

The Völkisch movement emerged in the late 19th century, drawing inspiration from German Romanticism and its fascination for a medieval Reich supposedly organized into a harmonious hierarchical order. Erected on the idea of "blood and soil", it was a racialist, populist, agrarian, romantic nationalist and an antisemitic movement from the 1900s onward as a consequence of a growing exclusive and racial connotation.[43] They idealized the myth of an "original nation", that still could be found at their times in the rural regions of Germany, a form of "primitive democracy freely subjected to their natural elites."[38] Thinkers led by Arthur de Gobineau, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Alexis Carrel and Georges Vacher de Lapouge distorted Darwin's theory of evolution to advocate a "race struggle" and an hygienist vision of the world. The purity of the bio-mystical and primordial nation theorized by the Völkischen then began to be seen as corrupted by foreign elements, Jewish in particular.[43]

Translated in Maurice Barrès' concept of "the earth and the dead", these ideas influenced the pre-fascist "revolutionary right" across Europe. The latter had its origin in the fin de siècle intellectual crisis and it was, in the words of Fritz Stern, the deep "cultural despair" of thinkers feeling uprooted within the rationalism and scientism of the modern world.[44] It was characterized by a rejection of the established social order, with revolutionary tendencies and anti-capitalist stances, a populist and plebiscitary dimension, the advocacy of violence as a means of action and a call for individual and collective palingenesis.[45]

Contemporary thought

The key thinkers of contemporary far-right politics are claimed by Mark Sedgwick to share four key elements, namely apocalyptism, fear of global elites, belief in Carl Schmitt's friend-enemy distinction and the idea of metapolitics.[46] The apocalyptic strain of thought begins in Oswald Spengler's The Decline of the West and is shared by Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist. It continues in The Death of the West by Pat Buchanan as well as in the fears of Islamization of Europe.[46] Related to it is the fear of global elites, who are seen as responsible for the decline.[46] Ernst Jünger was concerned about rootless cosmopolitan elites while de Benoist and Buchanan oppose the managerial state and Curtis Yarvin is against "the Cathedral".[46] Schmitt's friend-enemy distinction has inspired the French Nouvelle Droite idea of ethnopluralism which has become highly influential on the alt-right when combined with American racism.[46]

In a 1961 book deemed influential in the European far-right at large, French neo-fascist writer Maurice Bardèche introduced the idea that fascism could survive the 20th century under a new metapolitical guise adapted to the changes of the times. Rather than trying to revive doomed regimes with their single party, secret police or public display of Caesarism, Bardèche argued that its theorists should promote the core philosophical idea of fascism regardless of its framework,[6] i.e. the concept that only a minority, "the physically saner, the morally purer, the most conscious of national interest", can represent best the community and serve the less gifted in what Bardèche calls a new "feudal contract".[47]

Another influence on contemporary far-right thought has been the Traditionalist School which included Julius Evola and has influenced Steve Bannon and Aleksandr Dugin, advisors to Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin as well as the Jobbik party in Hungary.[48][49][50]

History by country

Rwanda

A number of far-right extremist and paramilitary groups carried out the Rwandan genocide under the racial supremacist ideology of Hutu Power, developed by journalist and Hutu supremacist Hassan Ngeze.[51] On 5 July 1975, exactly two years after the 1973 Rwandan coup d'état, the far right National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development (MRND) was founded under president Juvénal Habyarimana. Between 1975 and 1991, the MRND was the only legal political party in the country. It was dominated by Hutus, particularly from Habyarimana's home region of Northern Rwanda. An elite group of MRND party members who were known to have influence on the President and his wife Agathe Habyarimana are known as the akazu, an informal organization of Hutu extremists whose members planned and lead the 1994 Rwandan genocide.[52][53]

Interahamwe

The Interahamwe was formed around 1990 as the youth wing of the MRND and enjoyed the backing of the Hutu Power government. The Interahamwe were driven out of Rwanda after Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front victory in the Rwandan Civil War in July 1994 and are considered a terrorist organisation by many African and Western governments. The Interahamwe and splinter groups such as the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda continue to wage an insurgency against Rwanda from neighboring countries, where they are also involved in local conflicts and terrorism. The Interahamwe were the main perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide, during which an estimated 500,000 to 1,000,000 Tutsi, Twa and moderate Hutus were killed from April to July 1994 and the term Interahamwe was widened to mean any civilian bands killing Tutsi.[54][55]

Coalition for the Defence of the Republic

Other far-right groups and paramilitaries involved included the anti-democratic segregationist Coalition for the Defence of the Republic (CDR), which called for complete segregation of Hutus from Tutsis. The CDR had a paramilitary wing known as the Impuzamugambi. Together with the Interahamwe militia, the Impuzamugambi played a central role in the Rwandan genocide.[56][51]

Herstigte Nasionale Party

The far right in South Africa emerged as the Herstigte Nasionale Party (HNP) in 1969, formed by Albert Hertzog as breakaway from the predominant right-wing South African National Party, an Afrikaner ethno-nationalist party that implemented the racist, segregationist program of apartheid, the legal system of political, economic and social separation of the races intended to maintain and extend political and economic control of South Africa by the White minority.[57][58][59] The HNP was formed after the South African National Party re-established diplomatic relations with Malawi and legislated to allow Māori players and spectators to enter the country during the 1970 New Zealand rugby union team tour in South Africa.[60] The HNP advocated for a Calvinist, racially segregated and Afrikaans-speaking nation.[61]

Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging

In 1973, Eugène Terre'Blanche, a former police officer founded the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (Afrikaner Resistance Movement), a South African neo-Nazi paramilitary organisation, often described as a white supremacist group.[62][63][64] Since its founding in 1973 by Eugène Terre'Blanche and six other far-right Afrikaners, it has been dedicated to secessionist Afrikaner nationalism and the creation of an independent Boer-Afrikaner republic in part of South Africa. During negotiations to end apartheid in South Africa in the early 1990s, the organization terrorized and killed black South Africans.[65]

Togo

Togo has been ruled by members of the Gnassingbé family and the far-right military dictatorship formerly known as the Rally of the Togolese People since 1969. Despite the legalisation of political parties in 1991 and the ratification of a democratic constitution in 1992, the regime continues to be regarded as oppressive. In 1993, the European Union cut off aid in reaction to the regime's human-rights offenses. After's Eyadema's death in 2005, his son Faure Gnassingbe took over, then stood down and was re-elected in elections that were widely described as fraudulent and occasioned violence that resulted in as many as 600 deaths and the flight from Togo of 40,000 refugees.[66] In 2012, Faure Gnassingbe dissolved the RTP and created the Union for the Republic.[67][68][69]

Human rights

Throughout the reign of the Gnassingbé family, Togo has been extremely oppressive. According to a United States Department of State report based on conditions in 2010, human rights abuses are common and include "security force use of excessive force, including torture, which resulted in deaths and injuries; official impunity; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrests and detention; lengthy pretrial detention; executive influence over the judiciary; infringement of citizens' privacy rights; restrictions on freedoms of press, assembly, and movement; official corruption; discrimination and violence against women; child abuse, including female genital mutilation (FGM), and sexual exploitation of children; regional and ethnic discrimination; trafficking in persons, especially women and children; societal discrimination against persons with disabilities; official and societal discrimination against homosexual persons; societal discrimination against persons with HIV; and forced labor, including by children."[70]

Brazil

Prior to World War II, Nazis had been making and distributing propaganda among ethnic Germans in Brazil. The Nazi regime built close ties with Brazil through the estimated 100 thousand native Germans and 1 million German descendants living in Brazil at the time.[71] In 1928, the Brazilian section of the Nazi Party was founded in Timbó, Santa Catarina. This section reached 2,822 members and was the largest section of the Nazi Party outside Germany.[72][73][74] About 100 thousand born Germans and about one million descendants lived in Brazil at that time.[75]

During the 1920s and 1930s, a local brand of religious fascism appeared known as integralism a green-shirted paramilitary organization with uniformed ranks, highly regimented street demonstrations and rhetoric against Marxism and liberalism.[76][77] After Germany's defeat in World War II, many Nazi war criminals fled to Brazil and hid among the German-Brazilian communities. The most famous case was Josef Mengele, a doctor who became known as the "Angel of Death" at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Mengele performed horrific medical experiments. Mengele drowned in Bertioga, on the coast of São Paulo state, without ever having been recognized.[78]

The far right has continued to operate throughout Brazil[79] and a number of far-right parties existed in the modern era including Patriota, the Brazilian Labour Renewal Party, the Party of the Reconstruction of the National Order, the National Renewal Alliance and the Social Liberal Party as well as death squads such as the Command for Hunting Communists. President of Brazil Jair Bolsonaro is a member of the Alliance for Brazil, a far-right nationalist political group that aims to become a political party.[80][81][82] Bolsonaro has been widely described by numerous media organizations as far right.[83]

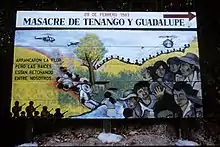

Central American death squads

In Guatemala, the far-right[84][85] government of Carlos Castillo Armas utilized death squads after coming to power in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état.[84][85] Along with other far-right extremists, Castillo Armas started the National Liberation Movement (Movimiento de Liberación Nacional, or MLN). The founders of the party described it as the "party of organized violence".[86] The new government promptly reversed the democratic reforms initiated during the Guatemalan Revolution and the agrarian reform program (Decree 900) that was the main project of president Jacobo Arbenz Guzman and which directly impacted the interests of both the United Fruit Company and the Guatemalan landowners.[87]

Mano Blanca, otherwise known as the Movement of Organized Nationalist Action, was set up in 1966 as a front for the MLN to carry out its more violent activities,[88][89] along with many other similar groups, including the New Anticommunist Organization and the Anticommunist Council of Guatemala.[86][90] Mano Blanca was active during the governments of colonel Carlos Arana Osorio and general Kjell Laugerud García and was dissolved by general Fernando Romeo Lucas Garcia in 1978.[91]

Armed with the support and coordination of the Guatemalan Armed Forces, Mano Blanca began a campaign described by the United States Department of State as one of "kidnappings, torture, and summary execution."[89] One of the main targets of Mano Blanca was the Revolutionary Party, an anti-communist group that was the only major reform oriented party allowed to operate under the military-dominated regime. Other targets included the banned leftist parties.[89] Human rights activist Blase Bonpane described the activities of Mano Blanca as being an integral part of the policy of the Guatemalan government and by extension the policy of the United States government and the Central Intelligence Agency.[87][92] Overall, Mano Blanca was responsible for thousands of murders and kidnappings, leading travel writer Paul Theroux to refer to them as "Guatemala's version of a volunteer Gestapo unit".[93]

Death squads in El Salvador

During the Salvadoran Civil War, far-right death squads known in Spanish by the name of Escuadrón de la Muerte, literally "Squadron of Death, achieved notoriety when a sniper assassinated Archbishop Óscar Romero while he was saying Mass in March 1980. In December 1980, three American nuns and a lay worker were gangraped and murdered by a military unit later found to have been acting on specific orders. Death squads were instrumental in killing thousands of peasants and activists. Funding for the squads came primarily from right-wing Salvadoran businessmen and landowners.[94]

El Salvadorian death squads indirectly received arms, funding, training and advice during the Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations.[95] Some death squads such as Sombra Negra are still operating in El Salvador.[96]

Death squads in Honduras

Honduras also had far-right death squads active through the 1980s, the most notorious of which was Battalion 3–16. Hundreds of people, teachers, politicians and union bosses were assassinated by government-backed forces. Battalion 316 received substantial support and training from the United States through the Central Intelligence Agency.[97] At least nineteen members were School of the Americas graduates.[98][99] As of mid-2006, seven members, including Billy Joya, later played important roles in the administration of President Manuel Zelaya.[100]

Following the 2009 Honduran constitutional crisis, former Battalion 3–16 member Nelson Willy Mejía Mejía became Director-General of Immigration[101][102] and Billy Joya was de facto President Roberto Micheletti's security advisor.[103] Napoleón Nassar Herrera, another former Battalion 3–16 member,[100][104] was high Commissioner of Police for the north-west region under Zelaya and under Micheletti, even becoming a Secretary of Security spokesperson "for dialogue" under Micheletti.[105][106] Zelaya claimed that Joya had reactivated the death squad, with dozens of government opponents having been murdered since the ascent of the Michiletti and Lobo governments.[103]

National Synarchist Union

The largest far-right party in Mexico is the National Synarchist Union. It was historically a movement of the Roman Catholic extreme right, in some ways akin to clerical fascism and Falangism, strongly opposed to the left-wing and secularist policies of the Institutional Revolutionary Party and its predecessors that governed Mexico from 1929 to 2000 and 2012 to 2018.[107][108]

United States

"Extreme right", "far-right" and "ultra-right" are labels used to describe "militant forms of insurgent revolutionary right ideology and separatist ethnocentric nationalism" such as Christian Identity, the Creativity Movement, the Ku Klux Klan, the National Socialist Movement and the National Alliance.[109] These groups share conspiracist views of power which are overwhelmingly antisemitic and reject pluralist democracy in favour of an organic oligarchy that would unite the perceived homogeneously-racial Völkish nation.[109]

Radical right

Starting in the 1870s and continuing through the late 19th century, numerous white supremacist paramilitary groups operated in the South, with the goal of organizing against and intimidating supporters of the Republican Party. Examples of such groups included the Red Shirts and the White League. The Second Ku Klux Klan, which was formed in 1915, combined Protestant fundamentalism and moralism with right-wing extremism. Its major support came from the urban south, the midwest and the Pacific Coast.[110] While the Klan initially drew upper middle class support, its bigotry and violence alienated these members and it came to be dominated by less educated and poorer members.[111]

The Ku Klux Klan claimed that there was a secret Catholic army within the United States loyal to the Pope, that one million Knights of Columbus were arming themselves and that Irish-American policemen would shoot Protestants as heretics. They claimed that the Catholics were planning to take Washington and put the Vatican in power and that all presidential assassinations had been carried out by Catholics. The prominent Klan leader D. C. Stephenson believed in the antisemitic canard of Jewish control of finance, claiming that international Jewish bankers were behind the World War I and planned to destroy economic opportunities for Christians. Other Klansmen in the Jewish Bolshevism conspiracy theory and claimed that the Russian Revolution and communism were controlled by Jews. They frequently reprinted parts of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and New York City was condemned as an evil city controlled by Jews and Catholics. The objects of the Klan fear tended to vary by locale and included African Americans as well as American Catholics, Jews, labour unions, liquor, Orientals and Wobblies. They were also anti-elitist and attacked "the intellectuals", seeing themselves as egalitarian defenders of the common man.[112] During the Great Depression, there were a large number of small nativist groups, whose ideologies and bases of support were similar to those of earlier nativist groups. However, proto-fascist movements such as Huey Long's Share Our Wealth and Charles Coughlin's National Union for Social Justice emerged which differed from other right-wing groups by attacking big business, calling for economic reform and rejecting nativism. Coughlin's group later developed a racist ideology.[113]

During the Cold War and the Red Scares, the far right "saw spies and communists influencing government and entertainment. Thus, despite bipartisan anticommunism in the United States, it was the right that mainly fought the great ideological battle against the communists."[114] The John Birch Society, founded in 1958, is a prominent example of a far-right organization mainly concerned with anti-communism and the perceived threat of communism. Neo-Nazi Robert Jay Matthews of the white supremacist group The Order came to support the John Birch Society, especially when conservative icon Barry Goldwater from Arizona ran for the presidency on the Republican Party ticket. Far-right conservatives consider John Birch to be the first casualty of the Cold War.[115] In the 1990s, many conservatives turned against then-president George H. W. Bush, who pleasured neither Republican Party's more moderate and far-right wings. As result, Bush was primared by Pat Buchanan. The 1994 United States elections resulted in major gains for Republicans when angry white men, enraged by advantages given to women and minorities, gained control of the United States Congress. The Republican Party's "Contract with America" established a far-right agenda for the next two years. In the 2000s, critics of President George W. Bush's conservative unilateralism argued it can be traced to both Vice President Dick Cheney who embraced the policy since the early 1990s and to far-right Congressmen who won their seats during the conservative revolution of 1994.[10]

Although small militias had existed throughout the latter half of the 20th century, the groups became more popular during the early 1990s, after a series of standoffs between armed citizens and federal government agents such as the 1992 Ruby Ridge siege and 1993 Waco Siege. These groups expressed concern for what they perceived as government tyranny within the United States and generally held constitutionalist, libertarian and right-libertarian political views, with a strong focus on the Second Amendment gun rights and tax protest. They also embraced many of the same conspiracy theories as predecessor groups on the radical right, particularly the New World Order conspiracy theory. Examples of such groups are the Oath Keepers and the Three Percenters. A minority of militia groups such as the Aryan Nations and the Posse Comitatus were white nationalists and saw militia and patriot movements as a form of white resistance against what they perceived to be a liberal and multiculturalist government. Militia and patriot organizations were involved in the 2014 Bundy standoff[116][117] and the 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.[118][119]

_crop.jpg.webp)

After the September 11 attacks in 2001, the counter-jihad movement, supported by groups such as Stop Islamization of America and individuals such as Frank Gaffney and Pamela Geller, began to gain traction among the American right. The counter-jihad members were widely dubbed Islamophobic for their vocal condemnation of the Islamic faith and their belief that there was a significant threat posed by Muslims living in America. Its proponents believed that the United States was under threat from "Islamic supremacism", accusing the Council on American-Islamic Relations and even prominent conservatives such as Suhail A. Khan and Grover Norquist of supporting radical Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood. The alt-right emerged during the 2016 United States presidential election cycle in support of the Donald Trump's presidential campaign. It draws influence from paleoconservatism, paleolibertarianism, white nationalism, the manosphere and the Identitarian and neoreactionary movements. The alt-right differs from previous radical right movements due to its heavy internet presence on websites such as 4chan.[120]

Uyoku dantai

In 1996, the National Police Agency estimated that there were over 1,000 extremist right-wing groups in Japan, with about 100,000 members in total. These groups are known in Japanese as Uyoku dantai. While there are political differences among the groups, they generally carry a philosophy of anti-leftism, hostility towards China, North Korea and South Korea and justification of Japan's role in World War II. Uyoku dantai groups are well known for their highly visible propaganda vehicles fitted with loudspeakers and prominently marked with the name of the group and propaganda slogans. The vehicles play patriotic or wartime-era songs. Activists affiliated with such groups have used Molotov cocktails and time bombs to intimidate moderate politicians and public figures, including former Deputy Foreign Minister Hitoshi Tanaka and Fuji Xerox Chairman Yotaro Kobayashi. An ex-member of a right-wing group set fire to Liberal Democratic Party politician Koichi Kato's house. Koichi Kato and Yotaro Kobayashi had spoken out against Koizumi's visits to Yasukuni Shrine.[121] Openly revisionist, Nippon Kaigi is considered "the biggest right-wing organization in Japan."[122][123]

Croatia

Individuals and groups in Croatia that employ far-right politics are most often associated with the historical Ustaše movement, hence they have connections to neo-Nazism and neo-fascism. That World War II political movement was an extremist organization at the time supported by the German Nazis and the Italian Fascists. The association with the Ustaše has been called neo-Ustashism by Slavko Goldstein.[124]

Estonia

Estonia's most significant far-right movement was the Vaps movement. Its ideological predecessor Valve Liit was founded by Admiral Johan Pitka and later banned for maligning the government. Vaps begun as the Union of Participants in the Estonian War of Independence, founded in 1921. The organization originally aimed to better the position of the veterans, but it became politicized quickly Vaps soon turned into a mass fascist movement.[125] The organisation advocated a fascist government government in Estonia,[126][127][128] and welcomed Hitler's rise to power, even though they later tried to distance themselves from Nazism.[126][129] In 1933, Estonians voted on Vaps' proposed changes to the constitution such as empowering the role of the State Elder and the changes were accepted with roughly 75% of Estonians voting in favor of the changes. In 1933, Vaps won 47 of the 87 seats in Tallinn municipal council while they won 33 out of 65 in Tartu. In 1934, Vaps candidate Andres Larka collected 62,000 votes for his election to the office of the State Elder while the incumbent Konstantin Päts collected meager 8,500. The Vaps were also predicted to win supermajority in the Parliament. However, the State Elder Konstantin Päts declared state of emergency and imprisoned the leadership of the Vaps. In 1935, all political parties were banned. In 1935, the Vaps coup attempt was discovered, which lead to the banning of the Blues-and-Blacks, the Finnish Patriotic People's Movement's youth wing that had been secretly aiding and arming them. Mysterious death of the Vaps leader Artur Sirk followed soon, leading many to speculate he had been killed by Päts' agents. The Blues-and-Blacks was reorganized as the Blackshirts and continued operating in Finland, unlike its fellow Estonian movement.[130][131]

During World War II, the Estonian Self-Administration was a collaborationist pro-Nazi government set up in Estonia, headed by Vaps member Hjalmar Mäe.[132] In the 21st century, the coalition-governing Conservative People's Party of Estonia been described as far right.[133] The neo-Nazi terrorist organization Feuerkrieg Division was found and operates in the country.[134] Some members of the Conservative Party allegedly have links to the Feuerkrieg Division.[135][136][137] The party's youth organisation Blue Awakening is the main organizer of the annual torchlight march through Tallinn on 24 February, Independence Day of Estonia. The event has been harshly criticized by the Simon Wiesenthal Center that described it as "Nuremberg-esque" and likened the ideology of the participants to that of the Estonian nazi collaborators.[138][139]

Finland

In Finland, the far right was strongest in 1920–1940 when the Academic Karelia Society, Lapua Movement, Patriotic People's Movement and Vientirauha operated in the country and had hundreds of thousands of members.[140] In addition to these dominant far-right organizations, smaller Nazi parties operated as well, among them the Finnish People's Organization (SKJ) led by Jäger-Captain Arvi Kalsta and Thorvald Oljemark with 20,000 members and the Blue Cross with 12,000 members. Even the Swedish-speaking Finns had their own Nazi organization, the People's Community Society led by the former governor Admiral Hjalmar von Bonsdorff and the Black Guard led by Örnulf Tigerstedt.[141][142][143] The groups exercised considerable political power, pressuring the government to outlaw communist parties and newspapers and expel Freemasons from the armed forces.[144][145] The groups also attacked left-wing events and politicians systematically, resulting in deaths. Minister of the Interior Heikki Ritavuori was assassinated for supposedly being too lenient towards communists.[146][144] Conservative and White Guard authorities supported the far right to a large extent. The social-democratic politician Onni Happonen was arrested by police who then turned him over to a fascist lynch mob to be killed.[147]

During the Cold War, all partied deemed fascist were banned according to the Paris Peace Treaties and all former fascist activists had to find new political homes.[148] Despite Finlandization, many continued in public life. Yrjö Ruutu, the leader of a Nazi party competing with the SKJ, joined the Finnish People's Democratic League. Juhani Konkka, the party secretary and editor-in-chief of the party newspaper National Socialist , abandoned politics and became an accomplished translator, receiving a cultural award of the Soviet Union.[149] Three former members of the Waffen SS served as ministers of defense, among them Finnish SS Battalion officers Sulo Suorttanen and Pekka Malinen as well as Mikko Laaksonen, a soldier in the Maschinengewehr-Ski-Bataillon "Finnland" consisting of pro-Nazi Finns who rejected the peace treaty.[150] During the Cold War, far-right activism was limited to small illegal groups like the clandestine neo-Nazi occultist group led by Pekka Siitoin, who made headlines after arson and bombing of the printing houses of the Communist Party of Finland. The Nordic Realm Party (NRP) also had some supporters,[151][152] with Seppo Seluska convicted of the torture and murder of a gay Jew.[153][154][155]

The skinhead culture gained momentum during the late 1980s and peaked during the late 1990s. In 1991, Finland received a number of Somali immigrants who became the main target of Finnish skinhead violence in the following years, including four attacks using explosives and a racist murder. Asylum seeker centres were attacked in Joensuu as skinheads would force their way into an asylum seeker centre and start shooting with shotguns. At worst, Somalis were assaulted by 50 skinheads at the same time.[156][157]

In 2013, the Simon Wiesenthal Centre asked president Niinistö to condemn a neo-Nazi newspaper circulated to some 660,000 households. The newspaper published articles denying the Holocaust and articles such as "Zionist terrorism" and "CNN, Goldman Sachs and Zionist Control" translated from David Duke.[158][159][160] The most prominent neo-Nazi group was the Nordic Resistance Movement, which is tied to multiple murders, attempted murders and assaults of political enemies was found in 2006 and proscribed in 2019.[161] The second biggest Finnish party, the Finns Party, has been described as far right.[162][163][164][165]

The NRM and other far-right nationalist parties organized an annual torch march demonstration in Helsinki on the Finnish independence day which ends at the Hietaniemi cemetery where members visit the tomb of Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim and the monument to the Finnish SS Battalion. The event was protested by antifascists, leading to counterdemonstrators being violently assaulted by NRM members who acted as security. The demonstration attracted close to 3,000 participants according to the estimates of the police and hundreds of officers patrol Helsinki to prevent violent clashes.[166][167][168][169] The march was attended and promoted by the Finns Party while it was condemned by left-wing parties. Iiris Suomela of the Green League characterized it as "obviously neo-Nazi" and expressed her disappointment in it being attended by such a large number of people.[170]

France

The largest far-right party in Europe is the French anti-immigration party National Rally, formally known as the National Front.[171][172] The party was founded in 1972, uniting a variety of French far-right groups under the leadership of Jean-Marie Le Pen.[173] Since 1984, it has been the major force of French nationalism.[174] Jean-Marie Le Pen's daughter Marine Le Pen was elected to succeed him as party leader in 2012. Under Jean-Marie Le Pen's leadership, the party sparked outrage for hate speech, including Holocaust denial and Islamophobia.[175][176]

Germany

In 1945, the Allied powers took control of Germany and banned the swastika, Nazi Party and the publication of Mein Kampf. Explicitly Nazi and neo-Nazi organizations are banned in Germany.[177] In 1960, the West German parliament voted unanimously to "make it illegal to incite hatred, to provoke violence, or to insult, ridicule or defame 'parts of the population' in a manner apt to breach the peace." German law outlaws anything that "approves of, glorifies or justifies the violent and despotic rule of the National Socialists."[177] Section 86a of the Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code) outlaws any "use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations" outside the contexts of "art or science, research or teaching". The law primarily outlaws the use of Nazi symbols, flags, insignia, uniforms, slogans and forms of greeting.[178] In the 21st century, the German far right consists of various small parties and two larger groups, namely Alternative for Germany and Pegida.[177][179][180][181]

Metaxism

The far right in Greece first came to power under the ideology of Metaxism, a proto-fascist ideology developed by dictator Ioannis Metaxas.[182] Metaxism called for the regeneration of the Greek nation and the establishment of an ethnically homogeneous state.[183] Metaxism disparaged liberalism, and held individual interests to be subordinate to those of the nation, seeking to mobilize the Greek people as a disciplined mass in service to the creation of a "new Greece".[183]

The Metaxas government and its official doctrines are often to conventional totalitarian-conservative dictatorships such as Francisco Franco's Spain or António de Oliveira Salazar's Portugal.[182][184] The Metaxist government derived its authority from the conservative establishment and its doctrines strongly supported traditional institutions such as the Greek Orthodox Church and the Greek Royal Family; essentially reactionary, it lacked the radical theoretical dimensions of ideologies such as Italian Fascism and German Nazism.[182][184]

Axis occupation of Greece and aftermath

The Metaxis regime came to an end after the Axis powers invaded Greece. The Axis occupation of Greece began in April 1941.[185] The occupation ruined the Greek economy and brought about terrible hardships for the Greek civilian population.[186] The Jewish population of Greece was nearly eradicated. Of its pre-war population of 75–77,000, only around 11–12,000 survived, either by joining the resistance or being hidden.[187] Following the short-lived interim government of Georgios Papandreou, the far right again seized power in Greece during the 1967 Greek coup d'état murdering Papandreou and replacing the interim government with the far right, United States-backed Greek junta. The Junta was a series of far-right military juntas that ruled Greece from 1967 to 1974. The dictatorship was characterised by right-wing cultural policies, restrictions on civil liberties and the imprisonment, torture and exile of political opponents. The junta's rule ended on 24 July 1974 under the pressure of the Turkish invasion of Cyprus, leading to the Metapolitefsi ("regime change") to democracy and the establishment of the Third Hellenic Republic.[188][189]

In the 21st century, the dominant far-right party in Greece is the neo-Nazi[190][191][192][193][194][195][196] and Mataxist inspired[197][198][199][200][201] Golden Dawn.[202][203][204][205][206] At the May 2012 Greek legislative election, Golden Dawn won a number of seats in the Greek parliament, the party received 6.92% of the vote.[207][208] Founded by Nikolaos Michaloliakos, Golden Dawn had its origins in the movement that worked towards a return to right-wing military dictatorship in Greece. Following an investigation into the 2013 murder of Pavlos Fyssas, an anti-fascist rapper, by a supporter of the party,[209] Michaloliakos and several other Golden Dawn parliamentarians and members were arrested and held in pre-trial detention on suspicion of forming a criminal organization.[210] The trial began on 20 April 2015[211] and is ongoing as of 2019. Golden Dawn later lost all of its remaining seats in the Greek Parliament in the 2019 Greek legislative election.[212] A 2020 survey showed the party's popularity plummeting to just 1.5%, down from 2.9% in previous year's elections.[213]

Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was an Axis power during World War II. By 1944, Hungary was in secret negotiations with the Allies. Upon discovering these secret negotiations Germany invaded Hungary in March 1944, effectively sabotaging the attempts to jump out of the war until the Budapest Offensive started later that same year.[214]

Jobbik

Hungary's largest far-right organisation is the Movement for a Better Hungary, commonly known as Jobbik, a radical Hungarian nationalist party.[215][216][217] The party describes itself as "a principled, conservative and radically patriotic Christian party", whose "fundamental purpose" is the protection of "Hungarian values and interests".[218] In 2014, the party has been described as an "anti-Semitic organization" by The Independent and a "neo-Nazi party" by the president of the European Jewish Congress.[219]

Italy

The far right has maintained a continuous political presence in Italy since the fall of Mussolini. The neo-fascist party Italian Social Movement (1946–1995), influenced by the previous Italian Social Republic (1943–1945), became one of the chief reference points for the European far-right from the end of World War II until the late 1980s.[220]

Silvio Berlusconi and his Forza Italia party dominated politics from 1994. According to some scholars, it gave neo-fascism a new respectability.[221] Caio Giulio Cesare Mussolini, great-grandson of Benito Mussolini, stood for the 2019 European Parliament election as a member of the far right Brothers of Italy party.[221] In 2011, it was estimated that the neo-fascist CasaPound party had 5,000 members.[222] The name is derived from the fascist poet Ezra Pound. It has also been influenced by the Manifesto of Verona, the Labour Charter of 1927 and social legislation of fascism.[223] There has been collaboration between CasaPound and the identitarian movement.[224]

The European migrant crisis has become an increasingly divisive issue in Italy.[225] Interior Minister Matteo Salvini has been courting far-right voters. His Northern League party has become an anti-immigrant, nationalist movement. Both parties are using Mussolini nostalgia to further their aims.[221]

Netherlands

Despite being neutral, the Netherlands was invaded by Nazi Germany on 10 May 1940 as part of Fall Gelb.[226] About 70% of the country's Jewish population were killed during the occupation, a much higher percentage than comparable countries such as Belgium and France.[227] Most of the south of the country was liberated in the second half of 1944. The rest, especially the west and north of the country still under occupation, suffered from a famine at the end of 1944 known as the Hunger Winter. On 5 May 1945, the whole country was finally liberated by the total surrender of all German forces. Since the end of World War II, the Netherlands has had a number of small far-right groups and parties, the largest and most successful being the Party for Freedom lead by Geert Wilders.[228] Other far-right Dutch groups include the neo-Nazi Dutch Peoples-Union (1973–present),[229] the Centre Party (1982–1986), the Centre Party '86 (1986–1998), the Dutch Block (1992–2000), New National Party (1998–2005) and the ultranationalist National Alliance (2003–2007).[230][231]

Poland

Following the collapse of Communist Poland, the far-right ideology became visible. The pan-Slavic and neopagan Polish National Union political party at its peak was one of the larger groups active in the early 1990s, numbering then some 4,000 members and making international headlines for its antisemitism and anti-Catholicism. The National Revival of Poland, being a marginal political party under the leadership of Adam Gmurczyk, operates since the late 1980s. It is a member of European National Front and a co-founder of International Third Position. The organization Association for Tradition and Culture "Niklot" was founded in 1998 by Tomasz Szczepanski, a former NOP member, promoting Slavic supremacy and neopaganism. Since the mid-1990s, the ultra-Catholic Radio Maryja station has been on air with an anti-modernist, nationalist and xenophobic program.[232]

The All-Polish Youth and National Radical Camp were recreated in 1989 and 1993, respectively becoming Poland's most prominent far-right organizations. In 1995, the Anti-Defamation League estimated the number of far-right and white power skinheads in Poland at 2,000, the fifth highest number after Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic and the United States.[233] Since late 2000s, native white power skinhead, white supremacy and neo-Nazi groups largely were absorbed into more casual and better organized Autonome Nationalisten. On the political level, the biggest victories achieved so far by the far right were in the 2001, 2005, 2015 and 2019 elections. The League of Polish Families won 38 seats in 2001 and 34 in 2005. In 2015, entering parliament from the list of Kukiz'15, the far right National Movement gained five seats out of Kukiz's forty-two. In April 2016, the National Movement leadership decided to break-off with Kukiz'15, but only one parliamentarian followed the party's instructions. The ones that decided to stay with Kukiz'15, together with few other Kukiz's parliamentarians, formed parliamentary nationalist association called National Democracy (Endecja).[234]

In 2019, the Confederation Liberty and Independence had the best performance of any far-right coalition to date, earning 1,256,953 votes which was 6.81% of the total vote in an election that saw a historically high turnout. Together, the coalition (although de-jure a party) earned eleven seats, distributed as five for KORWiN, five for National Movement and one for Confederation of the Polish Crown. Members of far-right groups make up a significant portion of those taking part in the annual Independence March in central Warsaw which started in 2009 to mark Independence Day. About 60,000 were in the 2017 march marking the 99th anniversary of independence, with placards such as "Clean Blood" seen on the march.[235]

Greater Romania Party

The preimenant far-right party in Romania is the Greater Romania Party, founded in 1991 by Tudor, who was formerly known as a "court poet" of Communist dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu[236] and his literary mentor, the writer Eugen Barbu, one year after Tudor launched the România Mare weekly magazine, which remains the most important propaganda tool of the PRM. Tudor subsequently launched a companion daily newspaper called Tricolorul. The historical expression Greater Romania refers to the idea of recreating the former Kingdom of Romania which existed during the interwar period. Having been the largest entity to bear the name of Romania, the frontiers were marked with the intent of uniting most territories inhabited by ethnic Romanians into a single country and it is now a rallying cry for Romanian nationalists. Due to internal conditions under Communist Romania after World War II, the expression's use was forbidden in publications until after the Romanian Revolution in 1989. The party's initial success was partly attributed to the deep rootedness of Ceaușescu's national communism in Romania.[237]

Both the ideology and the main political focus of the Greater Romania Party are reflected in frequently strongly nationalistic articles written by Tudor. The party has called for the outlawing of the ethnic Hungarian party, the Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania, for allegedly plotting the secession of Transylvania.[238]

Serbia

The far right in Serbia mostly focuses on national and religious factors and it refers to any manifestation of far-right politics in the Republic of Serbia. Today a large number of far-right groups operate in Serbia including the Serbian Radical Party, Serbian Party Oathkeepers, Leviathan Movement, Serbian Right and the explicitly neo-Nazi Nacionalni stroj (National Alignment). Nacionalni stroj was banned in Serbia in 2012.[239][240][241]

United Kingdom

The British far-right rose out of the fascist movement. In 1932, Oswald Mosley founded the British Union of Fascists (BUF) which was banned during World War II.[242] Founded in 1954 by A. K. Chesterton, the League of Empire Loyalists became the main British far-right group at the time. It was a pressure group rather than a political party, and did not contest elections. Most of its members were part of the Conservative Party and were known for politically embarrassing stunts at party conferences.[243] Other fascist parties included the National Front (NF), the White Defence League and the National Labour Party who eventually merged to form the British National Party (BNP).[244]

With the decline of the British Empire becoming inevitable, British far-right parties turned their attention to internal matters. The 1950s had seen an increase in immigration to the UK from its former colonies, particularly India, Pakistan, the Caribbean and Uganda. Led by John Bean and Andrew Fountaine, the BNP opposed the admittance of these people to the UK. A number of its rallies such as one in 1962 in Trafalgar Square ended in race riots. After a few early successes, the party got into difficulties and was destroyed by internal arguments. In 1967 it joined forces with John Tyndall and the remnants of Chesterton's League of Empire Loyalists to form Britain's largest far-right organisation, the National Front (NF).[245] The BNP and the NF supported extreme loyalism in Northern Ireland, and attracted Conservative Party members who had become disillusioned after Harold Macmillan had recognised the right to independence of the African colonies and had criticised Apartheid in South Africa.[246]

Some Northern Irish loyalist paramilitaries have links with far-right and neo-Nazi groups in Britain, including Combat 18,[247][248] the British National Socialist Movement[249] and the NF.[250] Since the 1990s, loyalist paramilitaries have been responsible for numerous racist attacks in loyalist areas.[251] During the 1970s, the NF's rallies became a regular feature of British politics. Election results remained strong in a few working-class urban areas, with a number of local council seats won, but the party never came anywhere near winning representation in parliament. Since the 1970s, the NF's support has been in decline whilst Nick Griffin and the BNP have grown in popularity. Around the turn of the 21st century, the BNP won a number of councillor seats. The party continued its anti-immigration policy[252] and a damaging BBC documentary led to Griffin being charged with incitement to racial hatred, although he was acquitted.[253]

Australia

Coming to prominence in Sydney with the formation of the New Guard (1931) and the Centre Party (1933), the far right has played a part in Australian political discourse since the second world war.[254] These proto-fascist groups were monarchist, anti-communist and authoritarian in nature. Early far-right groups were followed by the explicitly fascist Australia First Movement (1941).[255][256] The far right in Australia went on to acquire more explicitly racial connotations during the 1960s and 1970s, morphing into self-proclaimed Nazi, fascist and antisemitic movements, organisations that opposed non-white and non-Christian immigration such as the neo-Nazi National Socialist Party of Australia (1967) and the militant white supremacist group National Action (1982).[257][258][259]

Since the 1980s, the term has mainly been used to describe those who express the wish to preserve what they perceive to be Judeo-Christian, Anglo-Australian culture and those who campaign against Aboriginal land rights, multiculturalism, immigration and asylum seekers. Since 2001, Australia has seen the development of modern neo-Nazi, neo-fascist or alt-right groups such as the True Blue Crew, the United Patriots Front, Fraser Anning's Conservative National Party and the Antipodean Resistance.[260]

New Zealand

A small number of far-right organisations have existed in New Zealand since World War II, including the Conservative Front, the New Zealand National Front and the National Democrats Party.[261][262] Far-right parties in New Zealand lack significant support, with their protests often dwarfed by counter protest.[263] After the Christchurch mosque shootings in 2019, the National Front "publicly shut up shop"[264] and largely went underground like other far-right groups.[265]

Nationalist Vanua Tako Lavo Party

The Nationalist Vanua Tako Lavo Party was a far-right political party which advocated Fijian ethnic nationalism.[266] In 2009, party leader Iliesa Duvuloco was arrested for breaching the military regime's emergency laws by distributing pamphlets calling for an uprising against the military regime.[267] In January 2013, the military regime introduced regulations that essentially de-registered the party.[268][269]

Online

A number of far-right internet pages and forums are focused on and frequented by the far right. These include Stormfront and Iron March.

Stormfront

Stormfront is the oldest and most prominent neo-Nazi website,[270] described by the Southern Poverty Law Center and other media organizations as the "murder capital of the internet".[271] In August 2017, Stormfront was taken offline for just over a month when its registrar seized its domain name due to complaints that it promoted hatred and that some of its members were linked to murder. The Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law claimed credit for the action after advocating for Stormfront's web host, Network Solutions, to enforce its Terms of Service agreement which prohibits users from using its services to incite violence.[272]

Iron March

Iron March was a fascist web forum, founded by Russian nationalist Alexander "Slavros" Mukhitdinov founded in 2011. An unknown individual uploaded a database of Iron March users to the Internet Archive in November 2019 and multiple neo-Nazi users were identified, including an ICE detention center captain and several active members of the United States Armed Forces.[273][274] As of mid 2018, the Southern Poverty Law Center linked Iron March to nearly 100 murders.[275][273] Mukhitdinov remained a murky figure at the time of the leaks.[276]

Right-wing terrorism

Right-wing terrorism is terrorism motivated by a variety of far right ideologies and beliefs, including anti-communism, neo-fascism, neo-Nazism, racism, xenophobia and opposition to immigration. This type of terrorism has been sporadic, with little or no international cooperation.[277] Modern right-wing terrorism first appeared in western Europe in the 1980s and it first appeared in Eastern Europe following the dissolution of the Soviet Union.[278]

Right-wing terrorists aim to overthrow governments and replace them with nationalist or fascist-oriented governments.[277] The core of this movement includes neo-fascist skinheads, far-right hooligans, youth sympathisers and intellectual guides who believe that the state must rid itself of foreign elements in order to protect rightful citizens.[278] However, they usually lack a rigid ideology.[278]

According to Cas Mudde, far-right terrorism and violence in the West have been generally perpetrated in recent times by individuals or groups of individuals "who have at best a peripheral association" with politically relevant organizations of the far right. Nevertheless, Mudde follows, "in recent years far-right violence has become more planned, regular, and lethal, as terrorists attacks in Christchurch (2019), Pittsburgh (2018), and Utøya (2011) show."[21]

See also

References

- Other names:

- (Mudde 2002, p. 11)

- (Ignazi 2003)

- Baker, Peter (28 May 2016). "Rise of Donald Trump Tracks Growing Debate Over Global Fascism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- Aubrey, Stefan M. (2004). The New Dimension of International Terrorism. Zurich: vdf Hochschulverlag AG. p. 45. ISBN 3-7281-2949-6.

- Kopeček, Lubomír (2007). "The Far Right in Europe". Středoevropské politické studie. Central and Eastern European Online Library. IX (4): 280–293. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- (Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 21)

- Hilliard, Robert L.; Keith, Michael C. (1999). Waves of Rancor: Tuning in the Radical Right. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. p. 43.

- Fascism and Nazism:

alt-right, white supremacy:

- "Ctrl-Alt-Delete: The origins and ideology of the Alternative Right". Political Research Associates. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- Carlisle, Rodney. The Encyclopedia of Politics: The Left and the Right, Volume 2: The Right. Thousand Oaks, California, United States; London, England; New Delhi, India: Sage Publications, 2005. p. 693.

- Phipps, Alison (1 April 2019). "The Fight Against Sexual Violence". Soundings. 71 (71): 62–74. doi:10.3898/SOUN.71.05.2019.

- Ethnic persecution, forced assimilation, cleansing, etc.:

- Golder, Matt (11 May 2016). "Far Right Parties in Europe". Annual Review of Political Science. 19 (1): 477–497. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-042814-012441.

- Hilliard, Robert L.; Keith, Michael C. (1999). Waves of Rancor: Tuning in the Radical Right. Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe. p. 38.

- "Far Right Parties in Europe" (PDF).

- (Davies & Lynch 2002, p. 264)

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 22.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 21.

- Bar-On 2016, p. xiii.

- Mudde, Cas. "The Extreme Right Party Family: An Ideological Approach" (PhD diss., Leiden University, 1998).

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, pp. 44–45.

- Carlisle 2005, p. 694.

- Kopeček, Lubomír (2007). "The Far Right in Europe". Středoevropské politické studie. International Institute of Political Science, Masaryk University in Brno. IX (4): 280–293. Retrieved 21 December 2020 – via Central and Eastern European Online Library.

- Hilliard, Robert L. and Michael C. Keith, Waves of Rancor: Tuning in the Radical Right (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe 1999, p. 43.

- Woshinsky 2008, pp. 154–155.

- Widfeldt, Anders, "A fourth phase of the extreme right? Nordic immigration-critical parties in a comparative context". In: NORDEUROPAforum (2010:1/2), 7–31, Edoc.hu

- Kuligowski, Piotr; Moll, Łukasz; Szadkowski, Krystian (2019). "Anti-Communisms: Discourses of Exclusion". Praktyka teoretyczna. Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. 1 (31): 7–13. Retrieved 21 December 2020 – via Central and Eastern European Online Library.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, pp. 1–2; Mudde 2002, p. 10 agrees and notes that "the term is not only used for scientific purposes but also for political purposes. Several authors define right-wing extremism as a sort of anti-thesis against their own beliefs [...]."

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, pp. 1–2.

- Mudde 2002, p. 12.

- Bobbio, Norberto (1997). Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction. Translated by Cameron, Allan. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-06246-5.

- Woshinsky 2008, p. 156.

- Baker, Peter (28 May 2016). "Rise of Donald Trump Tracks Growing Debate Over Global Fascism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- Mudde 2019.

- Sedgwick, Mark (2019). Key Thinkers of the Radical Right: Behind the New Threat to Liberal Democracy. Oxford University Press. pp. xiii. ISBN 978-0-19-087760-6.

- William Safire. Safire's Political Dictionary. Oxford, England, UK: Oxford University Press, 2008. p. 385.

- Berlet, Chip; Lyons, Matthew N. (2000). Right-Wing Populism in America: Too Close for Comfort. New York: Guilford Press. p. 342.

- Filipović, Miroslava; Đorić, Marija (2010). "The Left or the Right: Old Paradigms and New Governments". Serbian Political Thought. 2 (1–2): 121–144. doi:10.22182/spt.2122011.8.

- Pavlopoulos, Vassilis (20 March 2014). Politics, economics, and the far right in Europe: a social psychological perspective. The Challenge of the Extreme Right in Europe: Past, Present, Future. Birkbeck, University of London.

- Choat, Simon (12 May 2017) "'Horseshoe theory' is nonsense – the far right and far left have little in common". The Conversation. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Rydgren, J. (2007) The Sociology of the Radical Right, Annual Review of Sociology, pp. 241–63

- Rydgren, J. (2007) The Sociology of the Radical Right, Annual Review of Sociology, p. 247

- Bornschier, Simon. (2010). Cleavage politics and the populist right the new cultural conflict in Western Europe. Temple University Press. OCLC 748925475.

- Merkel, P. and Weinberg, L. (2004) Right-wing Extremism in the Twenty-first Century, Frank Cass Publishers: London, pp 52–53

- Art, David (2011). Inside the Radical Right. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139498838.

- Allen, Trevor J. (8 July 2015). "All in the party family? Comparing far right voters in Western and Post-Communist Europe". Party Politics. 23 (3): 274–285. doi:10.1177/1354068815593457. ISSN 1354-0688. S2CID 147793242.

- Beiner, Ronald Verfasser. (12 March 2018). Dangerous Minds : Nietzsche, Heidegger, and the Return of the Far Right. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8122-9541-2. OCLC 1148094406.

- Beiner, Ronald Verfasser. (12 March 2018). Dangerous Minds : Nietzsche, Heidegger, and the Return of the Far Right. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-8122-9541-2. OCLC 1148094406.

- Bar-On, Tamir (7 December 2011), Backes, Uwe; Moreau, Patrick (eds.), "Intellectual Right – Wing Extremism – Alain de Benoist's Mazeway Resynthesis since 2000", The Extreme Right in Europe (1 ed.), Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, pp. 333–358, doi:10.13109/9783666369223.333, ISBN 9783525369227

- Woods, Roger (25 March 1996). The Conservative Revolution in the Weimar Republic. Springer. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9780230375857.

- Stéphane François (24 August 2009). "Qu'est ce que la Révolution Conservatrice ?". Fragments sur les Temps Présents (in French). Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, pp. 7–8.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, pp. 9–10.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, pp. 11–12.

- Dupeux, Louis (1994). "La nouvelle droite " révolutionnaire-conservatrice " et son influence sous la république de Weimar". Revue d'Histoire Moderne & Contemporaine. 41 (3): 474–75. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1994.1732.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, pp. 16–18.

- Stern, Fritz R. (1974). The Politics of Cultural Despair: A Study in the Rise of the Germanic Ideology. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520026438.

- Camus & Lebourg 2017, p. 19.

- Key thinkers of the radical right : behind the new threat to liberal democracy. Sedgwick, Mark J. New York, NY. 4 January 2019. ISBN 978-0-19-087760-6. OCLC 1060182005.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Desbuissons, Ghislaine (1990). "Maurice Bardèche, écrivain et théoricien fasciste?". Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine (in French). 37 (1): 148–159. doi:10.3406/rhmc.1990.1531. ISSN 0048-8003. JSTOR 20529642.

- Teitelbaum, Benjamin R. (21 April 2020). War for Eternity: The Return of Traditionalism and the Rise of the Populist Right. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-14-199204-4.

- Teitelbaum, Benjamin R. (21 April 2020). War for Eternity: The Return of Traditionalism and the Rise of the Populist Right. Penguin Books Limited. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-14-199204-4.

- Teitelbaum, Benjamin R. (21 April 2020). War for Eternity: The Return of Traditionalism and the Rise of the Populist Right. Penguin Books Limited. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-14-199204-4.

- Saha, Santosh C, ed. (2008). Ethnicity and sociopolitical change in Africa and other developing countries: a constructive discourse in state building (first ed.). Lexington Books. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-7391-2332-4.

- Aspegren, Lennart (2006). Never again?: Rwanda and the World. Human Rights Law: From Dissemination to Application — Essays in Honour of Göran Melander. The Raoul Wallenberg Institute human rights library. 26. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 173. ISBN 9004151818.

- Des Forges, Alison (March 1999). Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda – History → The Army, the Church and the Akazu. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1-56432-171-1.

- Reyntjens, Filip (21 October 2014). "Rwanda's Untold Story. A reply to "38 scholars, scientists, researchers, journalists and historians"". African Arguments.

- Des Forges, Alison (March 1999). Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda – The Organization → The Militia. New York: Human Rights Watch. ISBN 1-56432-171-1.

- "Rwanda genocide of 1994". Encyclopedia Britanica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. p. 3. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- "The End of Apartheid". Archive: Information released online prior to January 20, 2009. United States Department of State. 2009. Archived from the original on 5 February 2009. Retrieved 5 February 2009.

- "The prohibition of the African National Congress, the Pan-Africanist Congress, the South African Communist Party and a number of subsidiary organizations is being rescinded". www.cvet.org.za. CVET - Community Video Education Trust. 2 February 1990.

Organizations: Nationalist Party

- sahoboss (30 March 2011). "National Party (NP)".

- Brotz, Howard (1977). The Politics of South Africa: Democracy and Racial Diversity. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. p. 45. ISBN 9780192156716.

- Du Toit, Brian M. (1991). "The Far Right in Current South African Politics". The Journal of Modern African Studies. Cambridge University Press. 29 (4=): 627–67. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00005693. ISSN 1469-7777. JSTOR 161141.

- Turpin-Petrosino, Carolyn (2013). The Beast Reawakens: Fascism's Resurgence from Hitler's Spymasters to Today's Neo-Nazi Groups and Right-Wing Extremists. Taylor and Francis. ISBN 9781134014248.

There are hate groups in South Africa. Perhaps among the most organized is the Afrikaner Resistance Movement or AWB (Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging). Included in its ideological platform are neo-Nazism and White supremacy.

- "South Africa's neo-Nazis drop revenge vow". CNN. 5 April 2010.

- Clark, Nancy; Worger, William (2013). South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid. Routledge. p. xx. ISBN 9781317861652.

Terre'Blanche, Eugene (1941–2010): Began career in the South African police. In 1973 founded the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging as a Nazi-inspired militant right-wing movement upholding white supremacy.

- "Amnesty decision". Truth and Reconciliation Commission. 1999. Retrieved 22 April 2007.

- "Togo profile". BBC News. Retrieved 11 January 2013.

- "Togo : le RPT est mort, que vive l'Unir" (in French). Radio France Internationale. 15 April 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Yvette Attiogbé (14 April 2012). "The Dissolution of the RPT – It is Official". togo-online.co.uk. Archived from the original on 9 August 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Folly Mozolla (15 April 2012). "Faure Gnassingbé has created his party Union pour la République (UNIR) in Atakpamé". togo-online.co.uk. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 28 April 2012.