National anthem

A national anthem is a country's national song. The majority of national anthems are marches or hymns in style. Latin American, Central Asian, and European nations tend towards more ornate and operatic pieces, while those in the Middle East, Oceania, Africa, and the Caribbean use a more simplistic fanfare.[1] Some countries that are devolved into multiple constituent states have their own official musical compositions for them (such as with the United Kingdom, Russia, and the former Soviet Union); their constituencies' songs are sometimes referred to as national anthems even though they are not sovereign states.

| Part of a series on |

| Nationalism |

|---|

|

History

The custom of an officially adopted national anthem became popular in the 19th century.

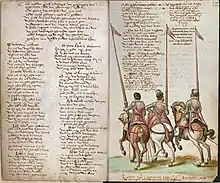

They are often patriotic songs that may have been in existence long before their designation as national anthem. The national anthem of the Netherlands, "Wilhelmus", officially adopted as national anthem in 1932, originates in the 16th century: It was written between 1568 and 1572 during the Dutch Revolt and its current melody variant was composed shortly before 1626, and was a popular orangist march during the 17th century. The Japanese national anthem, "Kimigayo" (adopted 1999), was composed in 1880, but its lyrics are taken from a Heian period (794–1185) poem.[3]

In the early modern period, some European monarchies adopted royal anthems. Some of these anthems have survived into current use. "God Save the King/Queen", first performed in 1619, remains the royal anthem of the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth realms. La Marcha Real, adopted as the royal anthem of the Spanish monarchy in 1770, was adopted as the national anthem of Spain in 1939. Denmark retains its royal anthem, Kong Christian stod ved højen mast (1780) alongside its national anthem (Der er et yndigt land, adopted 1835). In 1802, Gia Long commissioned a royal anthem in the European fashion for the Kingdom of Vietnam.

The first national anthem to be officially adopted was La Marseillaise, for the First French Republic. Composed in 1792, it was officially adopted by the French National Convention in 1796. It was retired in favour of Chant du départ under the First French Empire, and was re-instated in 1830, in the wake of the July Revolution. From this time, it became common for newly formed nations to define national anthems, notably as a result of the Latin American wars of independence, for Argentina (1813), Peru (1821), Brazil (1831) but also Belgium (1830).

Adoption of national anthems prior to the 1930s was mostly by newly formed or newly independent states, such as the First Portuguese Republic (A Portuguesa, 1911), the Kingdom of Greece ("Hymn to Liberty", 1865), the First Philippine Republic (Marcha Nacional Filipina, 1898), Lithuania (Tautiška giesmė, 1919), Weimar Germany (Deutschlandlied, 1922), Republic of Ireland (Amhrán na bhFiann, 1926) and Greater Lebanon ("Lebanese National Anthem", 1927).

The Olympic Charter of 1920 introduced the ritual of playing the national anthems of the gold medal winners. From this time, the playing of national anthems became increasingly popular at international sporting events, creating an incentive for such nations that did not yet have an officially defined national anthem to introduce one.

The United States introduced the patriotic song The Star-Spangled Banner as a national anthem in 1931. Following this, several nations moved to adopt as official national anthem patriotic songs that had already been in de facto use at official functions, such as Mexico (Mexicanos, al grito de guerra, composed 1854, adopted 1943) and Switzerland ("Swiss Psalm", composed 1841, de facto use from 1961, adopted 1981).

By the period of decolonisation in the 1960s, it had become common practice for newly independent nations to adopt an official national anthem. Some of these anthems were specifically commissioned, such as the anthem of Kenya, Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu, produced by a dedicated "Kenyan Anthem Commission" in 1963.[4]

A number of nations remain without an official national anthem. In these cases, there are established de facto anthems played at sporting events or diplomatic receptions. These include the United Kingdom ("God Save the Queen"), Sweden (Du gamla, Du fria) and Norway (Ja, vi elsker dette landet). Countries that have moved to officially adopt their long-standing de facto anthems since the 1990s include: Luxembourg (Ons Heemecht, adopted 1993), South Africa ("National anthem of South Africa", adopted 1997), Israel (Hatikvah, composed 1888, de facto use from 1948, adopted 2004), Italy (Il Canto degli Italiani, adopted 2017).

Usage

National anthems are used in a wide array of contexts. Certain etiquette may be involved in the playing of a country's anthem. These usually involve military honours, standing up/rising, removing headwear etc. In diplomatic situations the rules may be very formal. There may also be royal anthems, presidential anthems, state anthems etc. for special occasions.

They are played on national holidays and festivals, and have also come to be closely connected with sporting events. Wales was the first country to adopt this, during a rugby game against New Zealand in 1905. Since then during sporting competitions, such as the Olympic Games, the national anthem of the gold medal winner is played at each medal ceremony; also played before games in many sports leagues, since being adopted in baseball during World War II.[5] When teams from two nations play each other, the anthems of both nations are played, the host nation's anthem being played last.

In some countries, the national anthem is played to students each day at the start of school as an exercise in patriotism, such as in Tanzania.[6] In other countries the state anthem may be played in a theatre before a play or in a cinema before a movie. Many radio and television stations have adopted this and play the national anthem when they sign on in the morning and again when they sign off at night. For instance, the national anthem of China is played before the broadcast of evening news on Hong Kong's local television stations including TVB Jade.[7] In Colombia, it is a law to play the National Anthem at 6:00 and 18:00 on every public radio and television station, while in Thailand, "Phleng Chat Thai" is played at 08:00 and 18:00 nationwide (the Royal Anthem is used for sign-ons and closedowns instead).

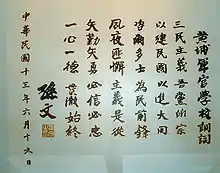

The use of a national anthem outside of its country, however, is dependent on the international recognition of that country. For instance, Taiwan has not been recognized by the International Olympic Committee as a separate nation since 1979 and must compete as Chinese Taipei; its "National Banner Song" is used instead of its national anthem.[8] In Taiwan, the country's national anthem is sung before instead of during flag-rising and flag-lowering, followed by the National Banner Song during the actual flag-rising and flag-lowering. Even within a state, the state's citizenry may interpret the national anthem differently (such as in the United States some view the U.S. national anthem as representing respect for dead soldiers and policemen whereas others view it as honoring the country generally).[9]

Creators

Most of the best-known national anthems were written by little-known or unknown composers such as Claude Joseph Rouget de Lisle, composer of "La Marseillaise" and John Stafford Smith who wrote the tune for "The Anacreontic Song", which became the tune for the U.S. national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner." The author of "God Save the Queen", one of the oldest and most well known anthems in the world, is unknown and disputed.

Very few countries have a national anthem written by a world-renowned composer. Exceptions include Germany, whose anthem "Das Lied der Deutschen" uses a melody written by Joseph Haydn, and Austria, whose national anthem "Land der Berge, Land am Strome" is sometimes credited to Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. The "Anthem of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic" was composed by Aram Khachaturian. The music of the "Pontifical Anthem", anthem of the Vatican City, was composed in 1869 by Charles Gounod, for the golden jubilee of Pope Pius IX's priestly ordination.

The committee charged with choosing a national anthem for the Federation of Malaya (later Malaysia) at independence decided to invite selected composers of international repute to submit compositions for consideration, including Benjamin Britten, William Walton, Gian Carlo Menotti and Zubir Said, who later composed "Majulah Singapura", the national anthem of Singapore. None were deemed suitable. The tune eventually selected was (and still is) the anthem of the constituent state of Perak, which was in turn adopted from a popular French melody titled "La Rosalie" composed by the lyricist Pierre-Jean de Béranger.

A few anthems have words by Nobel laureates in literature. The first Asian laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, wrote the words and music of "Jana Gana Mana" and "Amar Shonar Bangla", later adopted as the national anthems of India and Bangladesh respectively. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson wrote the lyrics for the Norwegian national anthem "Ja, vi elsker dette landet".

Other countries had their anthems composed by locally important people. This is the case for Colombia, whose anthem's lyrics were written by former president and poet Rafael Nuñez, who also wrote the country's first constitution. A similar case is Liberia, the national anthem of which was written by its third president, Daniel Bashiel Warner.

Languages

A national anthem, when it has lyrics (as is usually the case), is most often in the national or most common language of the country, whether de facto or official, there are notable exceptions. Most commonly, states with more than one national language may offer several versions of their anthem, for instance:

- The "Swiss Psalm", the national anthem of Switzerland, has different lyrics for each of the country's four official languages (French, German, Italian and Romansh).

- The national anthem of Canada, "O Canada", has official lyrics in both English and French which are not translations of each other, and is frequently sung with a mixture of stanzas, representing the country's bilingual nature. The song itself was originally written in French.

- "The Soldier's Song", the national anthem of Ireland, was originally written and adopted in English, but an Irish translation, although never formally adopted, is nowadays almost always sung instead, even though only 10.5% of Ireland speaks Irish natively.[10]

- The current South African national anthem is unique in that five of the country's eleven official languages are used in the same anthem (the first stanza is divided between two languages, with each of the remaining three stanzas in a different language). It was created by combining two songs together and then modifying the lyrics and adding new ones.

- One of the two official national anthems of New Zealand, "God Defend New Zealand", is now commonly sung with the first verse in Māori ("Aotearoa") and the second in English ("God Defend New Zealand"). The tune is the same but the words are not a direct translation of each other.

- "God Bless Fiji" has lyrics in English and Fijian which are not translations of each other. Although official, the Fijian version is rarely sung, and it is usually the English version that is performed at international sporting events.

- Although Singapore has four official languages, with English being the current lingua franca, the national anthem, "Majulah Singapura" is in Malay and by law can only be sung with its original Malay lyrics, despite the fact that Malay is a minority language in Singapore. This is because Part XIII of the Constitution of the Republic of Singapore declares, “the national language shall be the Malay language and shall be in the Roman script […]”

- There are several countries that do not have official lyrics to their national anthems. One of these is the "Marcha Real", the national anthem of Spain. Although it originally had lyrics those lyrics were discontinued after governmental changes in the early 1980s after Francisco Franco's dictatorship ended. In 2007 a national competition to write words was held, but no lyrics were chosen.[11] Other national anthems with no words include "Inno Nazionale della Repubblica", the national anthem of San Marino, that of Bosnia and Herzegovina, that of Russia from 1990 to 2000, and that of Kosovo, entitled "Europe".

- The national anthem of India, "Jana Gana Mana", the official lyrics are in Bengali; they were adapted from a poem written by Rabindranath Tagore.

- Despite the most common language in Wales being English, the Welsh National anthem "Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau" is sung in the Welsh language.

- The national anthem of Finland, "Maamme", was first written in Swedish and only later translated to Finnish. It is nowadays sung in both languages as there is a Swedish speaking minority of about 6% in the country. The national anthem of Estonia, "Mu isamaa, mu õnn ja rõõm" have similar melody with Finnish "Maamme", but only with different lyrics.[12]

See also

References

- Burton-Hill, Clemency (21 October 2014). "World Cup 2014: What makes a great national anthem?". BBC.com. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- M. de Bruin, "Het Wilhelmus tijdens de Republiek", in: L.P. Grijp (ed.), Nationale hymnen. Het Wilhelmus en zijn buren. Volkskundig bulletin 24 (1998), p. 16-42, 199–200; esp. p. 28 n. 65.

- Japan Policy Research Institute JPRI Working Paper No. 79.

- "Kenya". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Musical traditions in sports". SportsIllustrated.

- "Tanzania: Dons Fault Court Over Suspension of Students (Page 1 of 2)". allAfrica.com. 17 June 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2014.

- "Identity: Nationalism confronts a desire to be different". Financial Times. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Yomiuri Shimbun Foul cried over Taiwan anthem at hoop tourney. Published 6 August 2007

- "How national anthem became essential part of sports". USA TODAY. Retrieved 27 September 2017.

- "Census of Population 2016 – Profile 10 Education, Skills and the Irish Language - CSO - Central Statistics Office". Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- "Spain: Lost for words - The Economist". The Economist. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- YLE News: Why Finns don't want to change their national anthem

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to National anthem. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: National anthems |

Wikidata has the property:

|

- NationalAnthems.me, national anthems of every country in the world (and historical national anthems) with streaming audio, lyrics, information and links

- National Anthems (mp3 files)

- National Anthems of India in Hindi

- Nationalanthems.info, lyrics and history of national anthems

- Recordings of countries' anthems (mp3 files)

- Recordings of countries' anthems around the world by the United States Navy Band