Ned Kelly

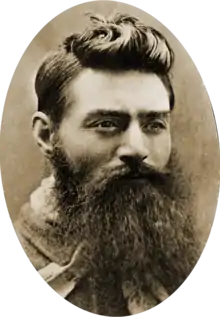

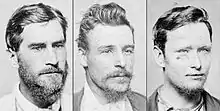

Ned Kelly (December 1854 – 11 November 1880)[lower-alpha 1] was an Australian bushranger, outlaw, gang leader and convicted police murderer. One of the last bushrangers, and by far the most famous, he is best known for wearing a suit of bulletproof armour during his final shootout with the police.

Ned Kelly | |

|---|---|

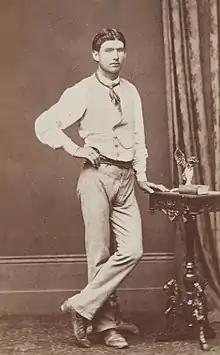

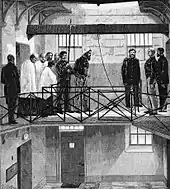

Kelly on 10 November 1880, the day before his execution | |

| Born | December 1854[lower-alpha 1] Beveridge, Colony of Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 11 November 1880 (aged 25) Melbourne, Colony of Victoria, Australia |

| Occupation | Bushranger |

| Criminal status | Executed by hanging |

| Parent(s) |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Conviction(s) | Murder, assault, theft, armed robbery |

| Criminal penalty | Death |

Kelly was born in the then-British colony of Victoria as the third of eight children to Irish parents. His father, a transported convict, died shortly after serving a six-month prison sentence, leaving Kelly, then aged 12, as the eldest male of the household. The Kellys were a poor selector family who saw themselves as downtrodden by the Squattocracy and as victims of persecution by the Victoria Police. While a teenager, Kelly was arrested for associating with bushranger Harry Power, and served two prison terms for a variety of offences, the longest stretch being from 1871 to 1874 on a conviction of receiving a stolen horse. He later joined the "Greta mob", a group of bush larrikins known for stock theft. A violent confrontation with a policeman occurred at the Kelly family's home in 1878, and Kelly was indicted for his attempted murder. Fleeing to the bush, Kelly vowed to avenge his mother, who was imprisoned for her role in the incident. After he, his younger brother Dan, and two associates—Joe Byrne and Steve Hart—shot dead three policemen, the Government of Victoria proclaimed them outlaws.

Kelly and his gang eluded the police for two years, thanks in part to the support of an extensive network of sympathisers. The gang's crime spree included raids on Euroa and Jerilderie, and the killing of Aaron Sherritt, a sympathiser turned police informer. In a manifesto letter, Kelly—denouncing the police, the Victorian government and the British Empire—set down his own account of the events leading up to his outlawry. Demanding justice for his family and the rural poor, he threatened dire consequences against those who defied him. In 1880, when Kelly's attempt to derail and ambush a police train failed, he and his gang, dressed in armour fashioned from stolen plough mouldboards, engaged in a final gun battle with the police at Glenrowan. Kelly, the only survivor, was severely wounded by police fire and captured. Despite thousands of supporters attending rallies and signing a petition for his reprieve, Kelly was tried, convicted and sentenced to death by hanging, which was carried out at the Old Melbourne Gaol. His last words were famously reported to have been, "Such is life".

Historian Geoffrey Serle called Kelly and his gang "the last expression of the lawless frontier in what was becoming a highly organised and educated society, the last protest of the mighty bush now tethered with iron rails to Melbourne and the world".[1] In the century after his death, Kelly became a cultural icon, inspiring numerous works in the arts and popular culture, and is the subject of more biographies than any other Australian. Kelly continues to cause division in his homeland: some celebrate him as Australia's equivalent of Robin Hood, while others regard him as a murderous villain undeserving of his folk hero status.[2] Journalist Martin Flanagan wrote: "What makes Ned a legend is not that everyone sees him the same—it's that everyone sees him. Like a bushfire on the horizon casting its red glow into the night."[3]

Family background and early life

Kelly's father, John Kelly (known as "Red"), was born in 1820 in Moyglass, near Cashel, County Tipperary, Ireland, to Thomas and Mary (née Cody). At the age of 21, he was found guilty of stealing two pigs[4] and was transported on the Prince Regent, arriving at Hobart Town, Van Diemen's Land on 2 January 1842. After he received his Certificate of Freedom on 11 January 1848, Red Kelly moved to Victoria and found work at James Quinn's farm at Wallan Wallan as a bush carpenter. He subsequently turned his attention to gold-digging, at which he was successful and which enabled him to purchase a small freehold for £615 in Beveridge, just north of Melbourne.

On 18 November 1850, at the age of 30, Red Kelly married Ellen Quinn, his employer's 18-year-old daughter, at St Francis Church by Father Gerald Ward.[5] Edward Kelly was his parents' third child,[6] named after Red's closest brother. The exact date of his birth is not known, but a number of lines of evidence, including a 1963 interview with family descendants Paddy and Charles Griffiths, a record from his mother, and a note from a school inspector, all suggest his birth was in December 1854. Ned Kelly was baptised by an Augustinian priest, Charles O'Hea, who also administered last rites to Kelly before his execution.

In 1864, the Kelly family moved to Avenel, near Seymour, where they soon attracted the attention of local police.[7] As a boy Kelly obtained basic schooling and became familiar with the bush. In Avenel he risked his life to save another boy from drowning in Hughes Creek;[8] the boy's family gave him a green sash, which he wore under his armour during his final showdown with police in 1880.[9]

In 1865, Red was imprisoned for having meat in his possession for which he could not account.[6][10] Unable to pay the twenty-five pound fine, he was sentenced to six months with hard labour, served at Kilmore Gaol.[11] Once released, Red drank heavily, which had an ultimately fatal effect on his health. In November 1866 his body started to swell from dropsy and he died at Avenel on 27 December 1866. He and his wife had eight children: Mary Jane (died as an infant aged 6 months), Annie (later Annie Gunn),[12] Margaret (later Margaret Skillion),[13] Ned, Dan, James, Kate and Grace (later Grace Griffiths).[14] The saga surrounding his father and his treatment by the police made a strong impression on the young Kelly. A few years later the family selected 88 acres (360,000 m2) of uncultivated and untitled farmland[15] at Eleven Mile Creek near the Greta area of Victoria.

In the dispute with the established graziers on whose land the Kellys were encroaching, they were suspected many times of cattle or horse stealing,[6] but never convicted. In all, eighteen charges were brought against members of Kelly's immediate family before he was declared an outlaw, while only half that number resulted in guilty verdicts. This is a highly unusual ratio for the time, and led to claims that Kelly's family was unfairly targeted from the time they moved to northeast Victoria. Perhaps the move was necessary because of Kelly's mother's squabbles with family members and her appearances in court over family disputes.[16] Author Antony O'Brien has argued that Victoria's colonial police practices treated arrest as equivalent to proof of guilt.[17]

Rise to notoriety

Bushranging with Harry Power

In 1869, aged fourteen, Kelly met Irish-born Harry Power (alias of Henry Johnson), a transported convict who turned to bushranging in North-Eastern Victoria after escaping Melbourne's Pentridge Prison. The Kellys formed part of his network of sympathisers, and by May 1869, Ned had become his bushranging protégé. At the end of the month, they attempted to steal horses from the Mansfield property of squatter John Rower as part of a plan to rob the Woods Point–Mansfield gold escort. They abandoned the idea and fled back into the bush after Rower shot at them, and Kelly temporarily broke off his association with Power.[18]

Kelly's first brush with the law occurred in mid-October 1869 over an altercation between him and a Chinese pig and fowl dealer from Morses Creek named Ah Fook. According to Fook, as he passed the Kelly family home, Ned brandished a long stick and declared himself a bushranger before robbing him of 10 shillings. Fook then travelled to Benalla to give his account of what happened to Sergeant James Whelan, who was, according to fellow officers, "a perfect encyclopedia of knowledge" about the Kellys and their criminal activities.[19] The next morning, Whelan chased down Kelly in the bush outside Greta and took him to Benalla, where he testified in court the next day that Fook abused his sister Annie for giving him creek water, not rain water, when, as a traveller, he requested a drink. Then, the story went, Fook beat Ned with a stick after he came to his sister's defence. Annie and two family-related witnesses corroborated Ned's story. Given that no other witnesses came forward, the charge was dismissed on 26 October and Kelly was released.[19]

Kelly reconciled with Power in March 1870, and over the next month, the pair committed a series of armed robberies as police scrambled to find them and identify Power's young accomplice. By the end of April, the press had named Kelly as the culprit, and a few days later, he was captured by police and confined to Beechworth Gaol. Kelly fronted court on three separate robbery charges, the first two of which were dismissed as none of the victims could positively identify him. On the third charge, the victims also reportedly failed to identify Kelly, but they were in fact refused a chance to identify him by Superintendents Nicolas and Hare. Instead, Nicolas told the magistrate that Kelly fitted the description and asked for him to be remanded for trial. He was sent to Melbourne where he spent the weekend in a lock-up before being transferred to Kyneton to face court. No evidence was produced in court, and he was released after a month. Historians tend to disagree over this episode: Some see it as evidence of police harassment; others believe that the Kelly family intimidated the witnesses, making them reluctant to give evidence. Another factor in the lack of identification may have been that the witnesses had described Power's accomplice as a "half-caste" (a person of Aboriginal and European descent). However, the police believed this to be the result of Kelly going unwashed.[19]

Power often camped at Glenmore Station, a large property owned by Kelly's maternal grandfather, James Quinn, which sat at the headwaters of the King River. In June 1870, while resting in a mountainside gunyah (bark shelter) that overlooked the property, Power was captured by a police search party. Following Power's arrest, word spread within the community that Kelly had informed on him. Kelly denied the rumour, and in a letter that bears the only surviving example of his handwriting, he pleads with Sergeant James Babington of Kyneton for help, saying that "everyone looks on me like a black snake". The informant turned out to be Kelly's uncle, Jack Lloyd, who received £500 for his assistance.

Reporting on Power's criminal career, the Benalla Ensign wrote:[19]

The effect of his example has already been to draw one young fellow into the open vortex of crime, and unless his career is speedily cut short, young Kelly will blossom into a declared enemy of society.

Horse theft, assault and imprisonment

In October 1870, a hawker, Jeremiah McCormack, accused a friend of the Kellys, Ben Gould, of stealing his horse. Gould wrote an indecent note to give to McCormack's childless wife, that was used to wrap two calves's testicles. Kelly passed it to one of his cousins to give to the woman. When McCormack confronted Kelly later that day, Kelly punched him in the nose, causing McCormack to fall. Kelly was arrested for his part in sending the calves' parts and the note and for assaulting McCormack. He was sentenced to three months' hard labour on each charge.

Kelly was released from Beechworth Gaol on 27 March 1871, five weeks early, and returned to Greta. Three weeks later, horse-breaker Isaiah "Wild" Wright arrived in town on what Kelly later described as a "very remarkable" chestnut mare. Wright visited the Kelly homestead to see his friend Alex Gunn, a Scottish miner who had married Kellys' older sister. Wright intended to ride the borrowed mare back to Mansfield, the home town of its owner, but discovered the next morning it had gone missing. Gunn lent him one of his own horses, promising that, if he found the mare, he would keep it until Wright returned. Soon after Wright departed, the mare was found by Gunn and a neighbour, William (Bricky) Williamson. Kelly then took the mare to Wangaratta, where he stayed for four days. On 20 April 1871, while riding back into Greta, Kelly was intercepted by Constable Edward Hall, who suspected that the horse was stolen. He directed Kelly to the police station on the pretence of having to sign some papers. As Kelly dismounted, Hall tried to grab him by the scruff of the neck, but failed. When Kelly resisted arrest, Hall drew his revolver and tried to shoot him, but it misfired three times. He was then overpowered by Kelly, who later said that he straddled him and dug spurs into his thighs, causing the constable to "[roar] like a big calf attacked by dogs". After subduing Kelly with the assistance of seven bystanders, Hall pistol-whipped him until his head became "a mass of raw and bleeding flesh".[20]

Although Kelly maintained that he did not know the mare belonged to someone other than Wright, he and Gunn were charged with horse stealing. When it was later revealed that Kelly was still imprisoned at Beechworth Gaol when the horse was taken, the charges were downgraded to "feloniously receiving a horse". Kelly and Gunn were sentenced to three years imprisonment with hard labour. Wright escaped arrest for the theft on 2 May following an "exchange of shots" with police, but was arrested the following day at the Kelly homestead and received eighteen months for stealing the horse.

Kelly served his sentence at Beechworth Gaol, then at HM Prison Pentridge near Melbourne. On 25 June 1873, Kelly's good behaviour earned him a transfer to the prison hulk Sacramento, anchored off Williamstown. He returned to Pentridge after several months and was released on 2 February 1874, six months early for good behaviour. That same month, his mother Ellen married an American, George King, with whom she had three children. King, Kelly and Dan Kelly became involved in cattle duffing.[21][22]

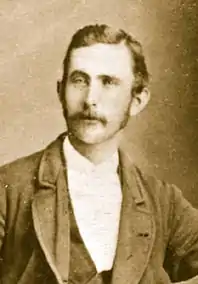

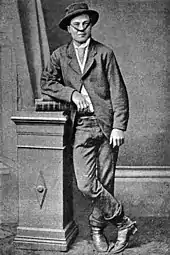

To settle the score with Wright over the chestnut mare, Kelly fought him in a bare-knuckle boxing match at the Imperial Hotel in Beechworth, 8 August 1874. Kelly won after 20 rounds and was declared the unofficial boxing champion of the district.[19] Soon afterwards, a Melbourne photographer took a portrait of Kelly in a boxing pose. Wright became an ardent supporter of Kelly.[23]

On 18 September 1877 in Benalla, Kelly, while drunk, was arrested for riding over a footpath and locked-up for the night. The next day, while he was escorted by four policemen, he absconded and ran, taking refuge in a shoemaker's shop. The police and the shop owner tried to handcuff him but failed. During the struggle Kelly's trousers were ripped off. Trying to get Kelly to submit and taking advantage of his torn trousers, the Irish-born Constable Thomas Lonigan, whom Kelly later murdered at Stringybark Creek, "black-balled" him (grabbed and squeezed his testicles).[24] During the struggle, a miller walked in, and on seeing the behaviour of the police said "You should be ashamed of yourselves." He then tried to pacify the situation and induced Kelly to put on the handcuffs.[25]

Kelly said about the incident, "It was in the course of this attempted arrest Fitzpatrick endeavoured to catch hold of me by the foot, and in the struggle he tore the sole and heel of my boot clean off. With one well-directed blow, I sent him sprawling against the wall, and the staggering blow I then gave him partly accounts to me for his subsequent conduct towards my family and myself."

It is reported that in the aftermath, Kelly ominously foreshadowed the crime that would eventually sentence him to death, and told Lonigan, "Well, Lonigan, I never shot a man yet. But if ever I do, so help me God, you'll be the first."[26]

Kelly was charged with being drunk and assaulting police. He was fined £3 1s, which included damage to the uniforms.[27]

In October 1877, Gustav and William Baumgarten were arrested for supplying stolen horses to Kelly. Gustav was discharged, but William was sentenced to four years jail in 1878, serving time at Pentridge Prison, Melbourne.[28]

Fitzpatrick incident

Fitzpatrick's version of events

On 15 April 1878, Constable Strachan, the officer in charge of the Greta police station, learned that Kelly was at a certain shearing shed and went to apprehend him. As lawlessness was rampant at Greta, it was recognised that the police station could not be left without protection and Constable Alexander Fitzpatrick, who, like the Kelly's, was also of Irish descent, was ordered there for relief duty. Fitzpatrick was aware of a warrant for Dan Kelly for horse stealing and he discussed with his sergeant at Benalla the idea of calling at the Kelly home on the way with the object of arresting Dan Kelly. The sergeant agreed with his actions, but warned him to be careful. He was instructed to proceed to Greta and rode through Wilton en route to Greta, stopping at the hotel there where he had one brandy and lemonade.

Finding Dan not at home, he remained with Kelly's mother and other family members, in conversation, for about an hour. According to Fitzpatrick, upon hearing someone chopping wood, he went to ensure that the chopping was licensed. The man proved to be William "Bricky" Williamson, a neighbour, who said that he needed a licence only if he was chopping on Crown land. (According to Williamson, he was at his own selection a half a mile from the Kelly's).

Fitzpatrick then observed two horsemen making towards the house he had just left. The men proved to be the teenager Dan Kelly and his brother-in-law, Bill Skillion. Fitzpatrick returned to the house and made the arrest. Dan asked to be allowed to have dinner before leaving. The constable consented, and stood near his prisoner. Whilst the constable was standing guard over Dan Kelly, the elder brother, Ned, rushed in and shot him in the left arm, two inches above the wrist, with a revolver. At the same time Ellen Kelly, Ned's mother, attacked Fitzpatrick hitting him over the head with a fire shovel, knocking him senseless.

Fitzpatrick stated that all except Kelly's mother had been armed with revolvers, that Kelly had shot him in the left wrist, and that Ellen Kelly had hit him on the helmet with a coal shovel.

On regaining consciousness, he was compelled by Ned Kelly to extract the bullet from his arm with a knife, so that it might not be used as evidence; and on promising to make no report against his assailants, he was allowed to depart. He had ridden away about a mile when he found that two horsemen were pursuing, but by spurring his horse into a gallop he escaped to the Winton hotel where he was assisted inside by the manager. He was offered a brandy and lemonade which he refused, but later accepted one drink. On regaining safety, he no longer considered the promise which he had made to the criminals as binding but reported the affair to his superior officer, when he reached Benalla accompanied by the hotel manager who rode with him.

Kelly's version of events

"The witness which can prove Fitzpatrick's falsehood can be found by advertising and if this is not done immediately horrible disasters shall follow. Fitzpatrick shall be the cause of greater slaughter to the rising generation than St. Patrick was to the snakes and toads in Ireland. For had I robbed, plundered, ravished and murdered everything I met my character could not be painted blacker than it as present but thank God my conscience is as clear as the snow in Peru".

— Kelly in a letter sent to Superintendent John Sadleir and parliamentarian Donald Cameron, December 1878[29]

In an interview three months before his execution, Kelly said that at the time of the incident, he was 200 miles from home, and according to him, his mother had asked Fitzpatrick if he had a warrant, and Fitzpatrick said that he had only a telegram, to which his mother said that Dan need not go. Fitzpatrick then said, pulling out a revolver, "I will blow your brains out if you interfere". His mother replied, "You would not be so handy with that popgun of yours if Ned were here". Dan then said, trying to trick Fitzpatrick, "There is Ned coming along by the side of the house". While he was pretending to look out of the window for Ned, Dan cornered Fitzpatrick, took the revolver and claimed that he had released Fitzpatrick unharmed.

Kelly asserted that he was not present, and that Fitzpatrick's wounds were self-inflicted. Kenneally, who interviewed the remaining Kelly brother, Jim Kelly, and Kelly cousin and gang providore Tom Lloyd, in addition to closely examining the 1881 report by the Royal Commission on the Police Force of Victoria, wrote that Fitzpatrick was drunk when he arrived at the Kellys, that while he was waiting for Dan, he made a pass at Kate, and Dan threw him to the floor. In the ensuing struggle, Fitzgerald drew his revolver, Ned appeared, and with his brother seized the constable, disarming him, but not before he struck his wrist against the projecting part of the door lock, an injury he claimed to be a gunshot wound.

After Ned Kelly was captured, he was asked by a journalist if Fitzpatrick tried to take liberties with his sister, Kate Kelly, he said "No, that is a foolish story; if he or any other policeman tried to take liberties with my sister, Victoria would not hold him". Kelly also admitted to having shot Fitzpatrick after his capture. Under oath, during Kelly's trial in Melbourne, Senior Constable Kelly described a conversation he had with Ned Kelly immediately after he had been captured at Glenrowan. “Between 3 and 6 the same morning had another conversation with prisoner in the presence of Constable Ryan. Gave him some milk and water. Asked him if Fitzpatrick’s statement was correct. Prisoner said, “Yes, I shot him”.

Trial

Williamson and Skillion were arrested for their part in the affair. Kelly and Dan were nowhere to be found, but Ellen was taken into custody, along with her baby, Alice. At the Benalla Court, on 17 May 1878, Williamson, Skillion and Ellen Kelly, while on remand, were charged with aiding and abetting attempted murder. The three appeared on 9 October 1878 before Judge Redmond Barry and charged with attempted murder. Despite Fitzpatrick's doctor reporting a smell of alcohol on the constable and his inability to confirm the wrist wound was caused by a bullet, Fitzpatrick's evidence was accepted by the police, the judge, and the jury. The three were convicted on Fitzpatrick's evidence. Fitzpatrick's evidence would later be corroborated by Williamson when he was interviewed in prison by Captain Frederick Standish. Mrs Kelly, Skillion and Williamson were tried and convicted of accessory to attempted murder against Fitzpatrick. Skillion and Williamson both received sentences of six years and Ellen three years of hard labour. Barry stated that if Kelly were present he would "give him 15 years". Frank Harty, a successful and well-known farmer in the area, offered to pay Ellen Kelly's bail upon which bail was immediately refused.

Ellen Kelly's sentence was considered unfair even by people who had no cause to be Kelly sympathizers. Alfred Wyatt, a police magistrate headquartered in Benalla, told the commission later that "I thought the sentence upon that old woman, Mrs Kelly, a very severe one." Enoch Downes, a truant officer, recounted to the commission in 1881 that while speaking to Joe Byrne's mother, he said that he did not believe in the sentence and "if policy had been used or consideration for the mother shown that two or three months would have been ample". When Kelly was executed, his mother was still in prison.

Stringybark Creek police murders

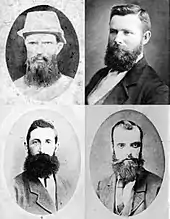

After the sentences were handed down in Benalla Police Court, both Ned and Dan Kelly doubted that they could convince the police of their story.[30] So they went into hiding, where they were later joined by friends Joe Byrne and Steve Hart.

The police had received information that the Kelly gang were in the Wombat Ranges, at the head of the King River. On 25 October 1878, two police parties were secretly dispatched—one from Greta, consisting of five men, with Sergeant Steele in command,[31] and one from Mansfield with four men, with the intention of executing a pincer movement.[32]

Sergeant Kennedy from the Mansfield party set off to search for the Kellys, accompanied by Constables McIntyre, Lonigan, and Scanlan. All were in civilian dress.[33] The police set up a camp on a disused diggings near two miners huts at Stringybark Creek in a heavily timbered area, a site suggested by Kennedy in a letter to Superintendent Sadleir, before the party had assembled, because of the distance between Mansfield and the King River and because the area was "so impenetrable".[34]

Early the next day, Kennedy and Scanlan went down to the creek to explore, leaving McIntyre to attend to camp duty. At about noon Lonigan heard a strange noise down by the creek and McIntyre went to investigate, hoping that it could be some kangaroos that he could shoot for dinner. Instead, he shot and killed some parrots which he cooked for dinner. (Unaware at the time, the sound of the shots alerted the bushrangers to their location.) At about 5pm, McIntyre was at the fire making tea, with Lonigan by him, when they were suddenly surprised by the Kelly gang with the cry, "Bail up, hold up your arms". McIntyre testified that Kelly took his fowling piece (shotgun), and that all the gang members were armed.[35] (Kelly stated that only two had guns.) Having left his revolver at the tent door, McInytre held up his hands as directed. Almost immediately Kelly shifted his aim from McIntyre to Lonigan and fired. Kelly shot him in the temple.[31] He fell to the ground and said, "Oh Christ, I am shot". He died a few seconds later. Kelly remarked, "What a pity; what made the fool run?"[31] Kelly had McIntyre searched and, when they found that he was unarmed, let him drop his hands. They took Lonigan and McIntyre's revolvers, and helped themselves to articles from the tent. Kelly talked to McIntyre and expressed his wonder that the police should have been so foolhardy as to look for him in the ranges. It was evident that he knew the exact state of the camp, the number of police and the description of the horses. He asked where the other two were, and told McIntyre he would kill him if he lied. McIntyre revealed their whereabouts and pleaded for their lives:

I told [Kelly] that they were both countrymen and co-religionists of his own. ... I thought he might be possessed of some of that patriotic-religious feeling which is such a bond of sympathy amongst the Irish people. My opinion is that he possessed none of this feeling. On the question of religion I believe he was apathetic, and like a great many young bushmen he prided himself more on his Australian birth than he did upon his extraction from any particular race. A favourite expression of his was: 'I will let them see what one native [native-born Australian] can do.'

McIntyre asked whether he was to be shot. Kelly replied, "No, why should I want to shoot you? Could I not have done it half an hour ago if I had wanted?" He added, "At first I thought you were Constable Flood. If you had been, I would have roasted you in the fire".[36] Kelly asked if the police came out to shoot him. "No", replied McIntyre, "we came to apprehend you". "What", asked Kelly, "brings you out here at all? It is a shame to see fine big strapping fellows like you in a lazy loafing billet like policemen".

McIntyre asked what they would do if he induced his comrades to surrender. Kelly stated, "I'll shoot no man if he holds up his hands", and that he would detain them all night, as he wanted a sleep, and let them go next morning without their guns or horses. McIntyre said that he would induce them to surrender if Kelly kept his word, and added that one of the two had many children. Kelly said, "You can depend on us". Kelly stated that Fitzpatrick was the cause of all this; that his mother and the rest had been unjustly "lagged" at Beechworth. He told McIntyre to leave the police force. McIntyre agreed, saying that he had thought about it for some time due to bad health. Ned asked McIntyre why their search party was carrying so much ammunition. McIntyre replied that it was to shoot kangaroos.[37]

At about 5:30pm Kelly then heard the approach of Kennedy and Scanlan, and the four gang members concealed themselves, some behind logs, and one in the tent. They forced McIntyre to sit on a log, and Kelly threatened, "Mind, I have a rifle for you if you give any alarm". Kennedy and Scanlan rode into the camp. McIntyre went forward and said, "Sergeant, I think you had better dismount and surrender, as you are surrounded". Kelly at the same time called out, "Put up your hands". Kennedy appeared to think it was Lonigan who called out, and that a jest was intended, for he smiled and put his hand on his revolver case. He was instantly fired at,[31] but not hit. Kennedy then realised the hopelessness of his position, jumped off his horse, and begged for his life, "It's all right, stop it, stop it". Scanlan's horse was disturbed and he tried to dismount but fell to the ground, and was on all fours. As he rose Kelly shot him in the right chest killing him almost instantly.

McIntyre, believing that the gang intended to shoot the whole party,[31] fled on Kennedy's horse. Several shots were fired at McIntyre as he dashed down the creek but none reached him, the rifles apparently being empty by that stage and only the revolvers available. Ned later wrote that he never intended to kill McIntyre "as I did not like to shoot him after he had surrendered".[38] McIntyre galloped through the scrub for two miles, and then his horse, evidently wounded, became exhausted. Suffering from a severe fall during his escape and with his clothes in tatters, McIntyre concealed himself in a wombat hole until dark, taking note of the direction of the setting sun. At about midnight, he set about to strike the Benalla road by trekking west, guided by a star. After crossing a number of streams, his feet became chafed, and had to walk with one of his boots off. After a rest, and using a match to illuminate a small compass, he travelled about 20 miles until he reached a farmhouse outside Mansfield, on Sunday afternoon. He then travelled by buggy to Mansfield and then directly to the residence of Sub-Inspector Pewtress.[39]

Two hours after McIntyre reported the murder of the troopers, Pewtress set out for camp, accompanied by McIntyre, Constable Allwood, Dr Reynolds, and five townspeople. They had only two rifles. They reached the camp with the assistance of a guide, Mr. Monk, at 2 am. There they found the bodies of Scanlan and Lonigan, as well as the tent burnt and possessions looted or destroyed. The post-mortem, by Dr Reynolds, showed that Lonigan had received four wounds, one through the eyeball. Scanlan's body had four shot-marks with the fatal wound caused by a rifle ball which went clean through the lungs. Ned later refuted this, saying "the coroner should be consulted".[40]

No trace had yet been discovered of Kennedy, and the same day as Scanlan and Lonigan's funeral, another failed search party was launched. His body was found a few days later by Henry G. Sparrow, several hundred metres north-west from the campsite, near Germans Creek.[41] The site of Kennedys' murder was claimed to be rediscovered in 2006.[42]

Outlawed under the Felons' Apprehension Act

In response to the public outrage at the murder of police officers, the reward was raised to £500, and on 31 October 1878, the Victorian Parliament passed the Felons' Apprehension Act, coming into effect on 1 November 1878, which outlawed the gang[43] and made it possible for anyone to shoot them: there was no need for the outlaws to be arrested or for there to be a trial upon apprehension (the act was based on the 1865 act passed in New South Wales which declared Ben Hall and his gang outlaws).[44][45] The act also penalized anyone who harboured, gave "any aid, shelter or sustenance" to the outlaws or withheld or gave false information about them to the authorities.[46] Punishment was "imprisonment with or without hard labour for such period not exceeding fifteen years".[46] With this new act in place, on 4 November 1878, warrants were issued against the four members of the Kelly gang. The deadline for their voluntary surrender was set at 12 November 1878.

Euroa raid

At midday on 9 December 1878, the Kelly gang held up Younghusband's Station, at Faithful's Creek, near the town of Euroa.[47] Ned assured the people that they had nothing to fear and only asked for food for themselves and their horses. An employee named Fitzgerald, who was eating dinner at the time, looked at Ned toying nonchalantly with a revolver, and said, "Well, of course, if the gentlemen want any refreshment they must have it".[48] The other three outlaws, having attended to the horses, joined Ned in imprisoning the men in a storeroom. No interference was offered to the women.[49] Late in the afternoon the manager of the station, Mr. McCauley, returned and was promptly held up.

Near sunset, hawker James Gloster arrived at the station to camp for the night. Earlier, he brushed off warnings that the place was held up by the Kelly gang, and when accosted by Ned, responded angrily and attempted to get a revolver from his wagon. Ned threatened to shoot him, saying it would be easy to do so if the hawker "did not keep a civil tongue in his head". Gloster asked the bushranger who he was. He responded: "I am Ned Kelly, the son of Red Kelly, and a better man never stood in two shoes." McCauley persuaded Gloster to surrender, and the pair joined the other prisoners in the storeroom. The Kellys stole new suits and a revolver from Gloster's stock as they wanted to look presentable at the bank. They offered the hawker money for them to which he refused. After sunset the hostages were allowed some fresh air.[50] Time passed quietly until 2 am, and at that hour the outlaws gave a peculiar whistle, and Hart and Byrne rushed from the building. McCauley was surrounded by the bushrangers and Kelly said, "You are armed, we have found a lot of ammunition in the house".[51] After this episode the outlaws retired to sleep.

The following afternoon, leaving Byrne in charge of the hostages, the other three axed the telegraph poles and cut the wires to sever the town's police link to Benalla. Three or four railway men endeavoured to interfere, but they too were taken hostage. The bushrangers then went to the bank with a small cheque drawn by McCauley. The bank having closed before their arrival, Ned forced the clerk to open it and cash the cheque. After taking £700 in notes, gold, and silver, Ned forced the manager to open the safe, from which the bushrangers got £1,500 in paper, £300 in gold, about £300 worth of gold dust and nearly £100 worth of silver. The reported total amount stolen was 68 £10 notes, 67 £5 notes, 418 £1 notes, £500 in sovereigns, about £90 in silver; and a 30oz ingot of gold.[52] The outlaws were polite and considerate to Scott's wife. Scott himself invited the outlaws to drink whisky with him, which they did. The whole party went to Younghusband's where the rest of the hostages were. The evening seems to have passed quite pleasantly. McCauley remarked to Kelly that the police might come along, which would mean a fight. Kelly replied, "I wish they would, for there is plenty of cover here".[53] In the evening, tea was prepared, and at half-past 8, the outlaws warned the hostages not to move for three hours, informing them that they were going. Just before they left, Kelly noticed that a Mr. McDougall was wearing a watch, and asked for it. McDougall replied that it was a gift from his dead mother. Kelly declared that he wouldn't take it under any consideration, and very soon afterwards the four of the outlaws left. What is unusual is that these stirring events happened without the people in the town knowing of anything.[54] The hostages left the station after five hours.[55]

Kelly sympathisers held

In January 1879 police under the command of Captain Standish, Superintendent Hare, and Officer Sadleir arrested all known Kelly friends and purported sympathisers, a total of 23 people, including Tom Lloyd[56] and Wild Wright, and held them without charge in Beechworth Gaol[57] for over three months. According to Hare:

All the responsible men in charge of different stations who had been a long time in Benalla—the detectives and officers—were all collected at Benalla by Captain Standish's orders. They ... all went into a room, and were asked the names of the persons in the district whom they considered to be sympathisers. I had nothing to do with it, merely listening and taking down names that fell from the mouths of men.[58]

Public opinion was turning against the police on the matter, and on 22 April 1879 the remainder of the sympathisers were released. None were given money or transported back to their home towns; all had to find their way back "25, 30, and even 50 miles" on their own.[59] The treatment of the 23 men caused resentment of the government's abuse of power that led to condemnation in the media and a groundswell of support for the gang that was a factor in their evading capture for so long.

Jerilderie raid

According to a Coonamble resident who encountered the Kellys at Glenrowan, Ned had heard that an individual named Sullivan had given evidence, and that he had travelled by train from Melbourne to Rutherglen. The Kelly gang then followed him there, but was told that he went to Uralla across the border in New South Wales. By the time they got to Uralla, Sullivan had left for Wagga Wagga. They followed him there but lost sight of him. Kelly thought that he might have travelled to Hay, so they took off in that direction but later gave up their chase. On their return home, they passed through Jerilderie, and the gang then decided to rob the bank.[60]

According to J.J. Kenneally, however, the gang arrived at Jerilderie having crossed the Murray River at Burramine. The group had heard of a crossing there, from where they could swim their horses but did not know where the landing place was on the opposite side of the river, so had Tom Lloyd investigate (the river was guarded by border police). After unsuccessfully trying to cross on his own, Lloyd employed the help of an owner of a hotel nearby, who pulled him across in a boat with Lloyd's horse paddling behind. After reporting the trip back to the rest of the gang, the group appropriated the boat to get across in two trips. Dan Kelly and Steve Hart reached Davidson's Hotel two miles south of Jerilderie on Saturday 2 February 1879 in time for tea, while the others waited in another area.[61]

At about midnight on 8 February, the gang surrounded the Jerilderie Police Station. Ned rode to the front and shouted for the policemen to come out, claiming there was a drunken brawl at Davidson's Hotel. Constables George Devine and Henry Richards emerged and asked the stranger for more information. Once Ned established there were no other policemen inside, the gang held them up and locked them in a cell.[62] Mary, Devine's wife, and their children were kept hostage inside the house as Ned stole all the firearms and ammunition. After this, he let them return to sleep, and with the rest of the gang stayed in the dining room until morning.[62]

There was a chapel in the courthouse, 100 yards from the barracks. Mrs Devine's duty was to prepare the courthouse for mass. The next day, Sunday, she was allowed to do so, but was accompanied by one of the Kellys. At about 10 am Kelly remained in the courthouse and helped Mrs Devine prepare the altar and dust the forms.[63] When this was done Kelly escorted her back to the barracks, where the door was closed and the blinds pulled to give the impression that the Devines were out. Hart and Dan Kelly, dressed in police uniform, walked to and from the stables during the day without attracting notice.

On Monday morning Byrne brought two horses to be shod, but the blacksmith suspected something strange in his manner, so he noted the horse's brands (according to Kenneally, the blacksmith was struck by the quality of these so-called police horses and thus noted their brands; according also to this version, the shoeing of the horses was charged to the government of New South Wales).[64] About 10 am the Kellys, with their hostage Constable Richards, went from the barracks, closely followed on horseback by Hart and Byrne. They all went to the Royal Hotel, where Cox, the landlord, told Richards that his companions were the Kellys. Ned Kelly said they wanted rooms at the Royal, and revealed his intentions to rob the bank. Hart and Byrne rode to the back and told the groom to stable their horses, but not to give them any feed. Hart went into the kitchen of the hotel, a few yards from the back entrance to the bank. Byrne then entered the rear of the bank, when he met the accountant, Mr Living, who told him to use the front entrance. Byrne displayed his revolver and induced him to surrender. Kenneally wrote, "The shock caused Living to stutter and it has been alleged that he stuttered for the rest of his life".[65] Byrne then walked him and Mackie, the junior accountant, into the bar, where Dan Kelly was on guard. Ned Kelly secured the bank manager, Mr Tarleton, who was ordered to open the safes. When this was done, he was put in with the others. All were liberated at a quarter to three.

After the manager had been secured, Ned Kelly took Living back to the bank and asked him how much money they had. Living admitted to between £600 and £700. Living then handed him the teller's cash, £691. Kelly asked if they had more money, and Living answered "No". Kelly tried to open the safe's treasure drawer, and one of the keys was given to him; but he needed the second key. Byrne wanted to break it open with a sledgehammer, but Kelly got the key from the teller and found £1650, making for a total of £2141 stolen from the bank. Kelly noticed a deed-box. The group then went to the hotel where Kelly burned three or four bank books containing mortgage documents, in an effort to erase the debts and create losses for the banks, though not realizing that some had copies held by the titles office in Sydney.[66][67]

Before leaving the hotel, Kelly made a speech to the hostages, mainly on the Fitzpatrick incident and the Stringybark killings. He then placed his revolver on the bar and announced, "Anyone here may take it and shoot me dead, but if I'm shot, Jerilderie shall swim in its own blood."[19] As the hotel's "roughs" cheered Kelly on, he learned that Hart had earlier stolen a watch from a local Methodist clergyman, Reverend J. B. Gribble, and forced him to return it.[19] The bushrangers then went to some of the other hotels, treating everyone civilly, and had drinks. Hart took a new saddle from the saddler's. Two splendid police horses were taken, and other horses were wanted, but the residents claimed that they belonged to women, and McDougall in order to keep his race mare "protested that he was a comparatively poor man"[68] and Kelly relented. The telegraph operators were also incarcerated. Byrne took possession of the office, and destroyed all the telegrams sent that day and cut all the wires.[69] The group left about 7 pm in an unknown direction. The disarmed and unhorsed police had no other means of following the gang.

Jerilderie Letter

I wish to acquaint you with some of the occurrences of the present past and future.

— Opening line of the Jerilderie Letter[70]

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Months prior to arriving in Jerilderie, Kelly composed a lengthy letter with the aim of tracing his path to outlawry, justifying his actions, and outlining the alleged injustices he and his family suffered at the hands of the police. He also decries the treatment of poor selector families by Victoria's Squattocracy, and, in "an escalating promise of revenge and retribution", invokes "a mythical tradition of Irish rebellion" against what he calls "the tyrannism of the English yoke".[71] Dictated to Byrne, it is known as the Jerilderie Letter, and is a handwritten document of 56 pages and 7,391 words. While holding up Jerilderie, Kelly gave the letter, which he called "a bit of my life", to Edwin Living, a local bank accountant, and demanded that he deliver it to the editor of the Jerilderie and Urana Gazette for publication.[72] Due to political suppression, only excerpts were published in the press, based on a copy transcribed by John Hanlon, owner of the Eight Mile Hotel in Deniliquin. The entire letter was rediscovered and published in 1930.[71]

The letter was Kelly's second attempt at writing a chronicle of his life and times. The first, known as the Cameron Letter, was sent to Donald Cameron, a member of the Victorian Parliament, in December 1878. Shorter than the Jerilderie Letter, it too was intended for a wide readership, but only a synopsis was published in the press.[73]

The original Jerilderie Letter was donated to the State Library of Victoria in 2000,[70] and Hanlon's transcript is held at Canberra's National Museum of Australia.[74] According to historian Alex McDermott, "Kelly inserts himself into history, on his own terms, with his own voice. ... We hear the living speaker in a way that no other document in our history achieves".[75] It has been interpreted as a proto-republican manifesto;[76] for others, it is a "murderous, ... maniacal rant",[77] and "a remarkable insight into Kelly's grandiosity".[78] Noted for its unorthodox grammar, the letter reaches "delirious poetics",[71] Kelly's language being "hyperbolic, allusive, hallucinatory ... full of striking metaphors and images".[70] His invective and sense of humour are also present; in one well-known passage, he calls the Victorian police "a parcel of big ugly fat-necked wombat headed, big bellied, magpie legged, narrow hipped, splaw-footed sons of Irish bailiffs or English landlords".[79] The letter closes:[80]

neglect this and abide by the consequences, which shall be worse than the rust in the wheat of Victoria or the druth of a dry season to the grasshoppers in New South Wales I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warning. but I am a widows son outlawed and my orders must be obeyed.

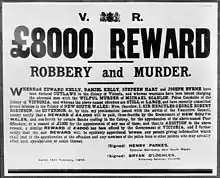

Reward increase and disappearance

In response to the Jerilderie raid, the New South Wales Government and several banks collectively issued £4,000 for the gang's capture, dead or alive, the largest reward offered in the colony since £5,000 was placed on the heads of the outlawed Clarke brothers in 1867.[81] The Victorian Government matched the offer for the Kelly gang, bringing the total amount to £8,000, bushranging's largest ever reward.[82] The Board of Officers, which included Captain Standish, Superintendents Hare and Sadleir, centralized all decisions about any search for the Kelly gang. The reward money had a demoralizing effect on them: "The capture of the Kellys was desired by these officers, but they were very jealous as to where they themselves would come in when the reward money would be allotted. This led to very serious quarrels among the heads..."[82]

From early March 1879 to June 1880, nothing was heard of the gang's whereabouts. As Thomas Aubrey wrote in his 1953 Mirror article,

In the months after Jerilderie, public opinion turned sharply against Commissioner Standish and the 300 officers and men of the police and artillery corps who crowded into the towns of North-Eastern Victoria. Critics were quick to point out that the brave constables took good care to remain in the towns leaving the outlaws almost complete freedom of the bush, their natural home.[83]

Amid low public confidence in the ability of the police, wrote Thomas Aubrey, "many believed that the gang had already made their escape to another colony while their pursuers wandered about Victoria receiving, but never earning, double pay and considerable 'danger' money". In the meantime, the gang were comfortably camped in the hills near the Kelly farm at Eleven Mile Creek, where they discussed police efforts and plans for their future.[83]

In February 1879, Captain Standish made a request to the Queensland Police Commissioner, David Thompson Seymour, to send a section of Native Police troopers to Victoria to aid in the search for the Kelly Gang. The request was granted with sub-Inspector Stanhope O'Connor, constable Tom King and six Aboriginal troopers named Sambo, Barney, Johnny, Jimmy, Jack and Hero, being deployed to Victoria.[84] O'Connor and his troopers, at the time of the request, were in active service in the Cooktown region conducting punitive expeditions against Indigenous communities and had recently massacred thirty people near Cape Bedford.[85] The ability of the Native Police troopers to locate Kelly was hampered early on with Sambo dying from pneumonia not long after arriving at the police barracks in Benalla.[86] Furthermore, Standish was fearful that if the Queensland contingent were to locate Kelly quickly, they would make the Victorian police appear incompetent, so he obstructed and withheld information from O'Connor's force.[87]

In late March 1879, Kelly's sisters Kate and Margaret asked the captain of the Victoria Cross how much he would charge to take "four or five gentlemen friends" to California from Queenscliff. On 31 March, an unidentified man arranged an appointment with the captain at the General Post Office to give a definite answer for the cost. The captain contacted police, who placed a large number of detectives and plain-clothes police throughout the building, but the man failed to appear. There is no evidence that Kelly's sisters were enquiring on behalf of the gang, and was reported in the Argus as "without foundation".[88]

According to Tom Lloyd, the gang "frequently discussed their plans for the future", and he suggested they go to Queensland one at a time where they could join up again. He felt that "a few years in the tropical climate" would render them unrecognizable. The gang came to the conclusion however that they would be forever estranged there and would lack the kind of whole-hearted support they had been getting in Victoria, and that their best recourse was to resolve their issues with the Victoria and New South Wales state governments.[89]

In late 1879, Kelly agreed to be interviewed in person by journalist J. F. Archibald of the Sydney Daily Telegraph, but it fell through when the newspaper refused to run the story.[90] On 9 February 1880, the Felons' Apprehension Act 1878 lapsed with the dissolution of the Berry Parliament, and the gang's outlaw status and their arrest warrants expired with it. While Ned and Dan still had prior warrants outstanding for the attempted murder of Fitzpatrick, technically Hart and Byrne were free men although the police could still re-issue the murder warrants.[91]

In April 1880 a "Notice of Withdrawal of Reward" was posted by the government. It stated that after 20 July 1880 the Government would "absolutely cancel and withdraw the offer for the reward".[92]

Glenrowan affair

Murder of Aaron Sherritt

... I look upon Ned Kelly as an extraordinary man; there is no man in the world like him, he is superhuman.

— Aaron Sherritt to Superintendent Hare[19]

During the Kelly outbreak, police watch parties monitored houses belonging to relatives of the gang, including that of Byrne's mother in the Woolshed Valley, near Beechworth. The police used the house of her neighbour, former Greta mob member and lifelong friend of Byrne, Aaron Sherritt, as a base of operations, sleeping in it during the day and keeping watch from nearby caves at night. Sherritt accepted police payments for camping with the watch parties and for providing information on the bushrangers' activities.[19] While many policemen suspected him of being a double agent for the gang, a detective, Michael Ward, planned to bring the bushrangers out of hiding by spreading rumours that Sherritt's true loyalties lay with the police.[93] Convinced that he was a traitor, the gang decided to murder Sherritt as part of their own plan, one that they boasted would "astonish not only the Australian colonies, but the whole world".[94]

On 26 June 1880, Dan and Byrne rode into the Woolshed Valley. That evening, they kidnapped Anton Wick, a German-born market gardener who lived near Sherritt, reassuring him that he would not be hurt if he obeyed their orders. While Dan went to the front door of Sherritt's hut, Byrne forced Wick to knock on the back door and call out. "What do you want?" asked Sherritt. Prompted by Byrne, Wick replied that he had lost his way. Sherritt opened the door and joked with his neighbour as Belle Sherritt, his wife, told him to give directions. As Sherritt raised his arm to point the way, he hesitated, saying, "Who's that?" Byrne then fired two shots and Sherritt staggered back, having been hit in the neck, severing his jugular. Byrne followed Sherritt into the hut and fired again, hitting him in the chest. Sherritt collapsed and died within a few minutes.[83] As he bled out, his wife and her mother, Ellen Barry, screamed in terror. Byrne told them, "That bastard will never put me away again."[95]

After ordering Ellen to unlock the front door for Dan, Byrne used Belle as a human shield as he fired into the bedroom where he knew four policemen were hiding: Robert Alexander, Henry Armstrong, Thomas Dowling and William Duross. Byrne sent Belle in to tell them to come out, but they pulled her to the floor. The outlaws then took Ellen outside and Byrne placed kindling around the hut, promising to "roast" everyone inside. He asked Ellen for kerosene, but she pleaded with him, saying, "For God's sake, my girl's in there." "Then get her out and bring those bloody traps with her," replied Byrne. Ellen went back inside, but she too was pulled to the floor.[95] The outlaws yelled more threats, then released Wick and rode off.[96]

Superintendent Hare later wrote:

It was doubtless a most fortunate occurrence that Aaron was shot by the outlaws; it was impossible to have reclaimed him, and the Government of the colony would not have assisted him in any way, and he would have gone back to his old course of life, and probably become a bushranger himself.[97]

Siege and shootout

The gang estimated that the policemen inside Sherritt's hut would relay news of his murder to Beechworth by early Sunday morning, prompting a special police train to be sent up from Melbourne. They also surmised that the train would collect reinforcements in Benalla before continuing through Glenrowan, a small town in the Warby Ranges. There, the gang planned to wreck the train and shoot dead any survivors, then ride to an unpoliced Benalla where they would rob the banks, set fire to the courthouse, blow up the police barracks, release anyone imprisoned in the gaol, and "generally play havoc with the entire town" before returning to the bush.[98] While Byrne and Dan were in the Woolshed Valley, Ned and Hart tried, but failed, to damage the track at Glenrowan, so they forced line-repairers camped nearby to finish the job. The outlaws selected a sharp curve in the line that ran across a deep ravine, and told their captives that they were going to "send the train and its occupants to hell".[99]

The bushrangers took over Glenrowan without meeting resistance from the locals, and imprisoned them at Ann Jones' Glenrowan Inn, while the other hotel in town, McDonnell's Railway Hotel, was used to stable the gang's stolen horses, one of which carried a tin of blasting powder and fuses. Their packhorses also carried suits of bullet-repelling armour, each complete with a helmet and weighing about 44 kilograms (97 lb). The gang made these suits with the intention of further robbing banks.[100] The police had been informed by their spies about the armour, but dismissed these claims as tall tales.[83]

By Sunday afternoon, the gang had gathered a total of 62 hostages at the hotel. As the hours passed without any sight of the train, the gang insisted that drinks be provided to the townspeople and that music be played.[101] They danced with hostages while the landlady's son sang bushranger ballads, including one about the Kelly gang.[102] Dan and Byrne became fairly drunk; Ned, however, abstained from drinking, and instead staged hop, step and jump and other games with the hostages, who were also encouraged by the bushrangers to amuse themselves with card games.[103] One hostage later testified, "[Ned] did not treat us badly—not at all".[102]

At about 10 pm, Ned and Byrne captured Glenrowan's lone constable, Bracken, with the assistance of hostage Thomas Curnow, a local schoolmaster who sought to gain the gang's trust in order to thwart their plans. Believing that Curnow was a sympathiser, Ned let him and his wife return home, but warned them to "go quietly to bed and not to dream too loud", as one of the gang would visit during the night. Back at the hotel, Kelly grew increasingly anxious over the train's non-arrival. The delay was caused by the fact that the policemen in Sherritt's hut waited until daylight to emerge and give the alarm, and news of the murder did not reach Melbourne until Sunday afternoon. Only at 1 am on Monday did a police train carrying troopers, native trackers and several journalists steam into Benalla to collect reinforcements. Upon hearing the train's approach at 3 am, Curnow, despite Kelly's warning, rushed to the line and warned the pilot train to stop by raising a lit candle behind a red scarf. He told the driver of the gang's plan. The trains then slowly made their way to Glenrowan.

Around this time, Kelly decided to let the townspeople return home, but Ann Jones told them to stay to hear the outlaw lecture. Byrne interrupted the conversation, alerting the group about the train's arrival. The gang prepared for action and hurried to dress in their armour. Bracken meanwhile told the hostages to lie low, and escaped to the railway station to explain the situation to the police. Superintendent Hare led six constables and five native trackers towards the hotel where the armour-clad outlaws waited for them on the verandah. As the police approached the police commander Superintendent Hare noticed a single figure standing on the verandah, who immediately opened fire on the police. The police returned fire and the other three gang members all dressed in their armour joined Ned Kelly. In the first volley, Supt Hare was hit in the left wrist, and Ned Kelly was wounded in the left hand and arm and he received a shot to his right foot that entered at the toes and exited at his heel.

The police and the gang fired at each other for about a quarter of an hour. During a lull, Superintendent Hare returned to the railway station with a shattered left wrist from one of the first shots fired. He bled profusely, and Tom Carrington, artist for the Australasian Sketcher, used his handkerchief to compress the wound. Hare then ordered O'Connor and his men to surround the hotel, and later attempted to return to battle, but gradually lost so much blood that he had to be sent to Benalla for treatment.

The Royal Commission found that Ned Kelly having retreated into the hotel after the first volley almost certainly walked out the back door for about 150 metres leading his horse. At about 100 metres he dropped his rifle and continued where he lay down behind a log until just after 7 am in the morning.

The police, trackers and civilian volunteers surrounded the hotel throughout the night, and the firing continued intermittently. At about 5 am, nine reinforcements under Superintendent Sadleir arrived from Benalla, followed soon after by Sergeant Steele, of Wangaratta, with six more policemen, for a total of about 30 men. Around this stage, Byrne made a toast while drinking whiskey at the bar, saying, "Many more years in the bush for the Kelly gang!" Moments later, a stray bullet passed through a small gap in his armour and severed his femoral artery, and he bled out within minutes. Before daylight, Senior-Constable Kelly found a revolving rifle and a silk cap lying in the bush, about 100 yards from the hotel. The rifle was covered with blood and a pool of blood lay near it. They believed it to belong to one of the bushrangers, hinting that they had escaped. They proved to be those of Ned Kelly himself. At daybreak, the women and children among the hostages were allowed to depart. They were challenged as they approached the police line, to ensure that the outlaws were not attempting to escape in disguise.

Last stand and capture

In the dim light of dawn, Kelly, dressed in his armour and armed with three handguns, rose out of the bush and attacked the police from their rear.[104] Several members of the scattered police line returned fire but to no effect as Kelly moved steadily through the morning mist towards the hotel, his armour repelling bullets. The size and shape of the armour made him appear inhuman to the police, and his apparent invulnerability caused onlookers to react with "superstitious awe".[105] Constable Arthur, the first policeman to encounter Kelly, recalled: "I was completely astonished, and could not understand what the object I was firing at was." One trooper exclaimed that it was a bunyip and could not be killed. A civilian volunteer cried out that it was the Devil. Journalist Tom Carrington wrote:[106]

With the steam rising from the ground, it looked for all the world like the ghost of Hamlet's father with no head, only a very long thick neck ... It was the most extraordinary sight I ever saw or read of in my life, and I felt fairly spellbound with wonder, and I could not stir or speak.

Kelly began laughing as he shot at and taunted the police, and called out to the remaining outlaws to recommence firing, which they did.[107] This "strange contest" continued for almost ten minutes. Kelly, weakened by blood loss, managed to advance 50 or so yards, at times stopping to change weapons or regain his composure after taking a bullet to the armour, the sensation being "like blows from a man's fist".[108] After diving to the ground to avoid one of Kelly's shots, Sergeant Steele realised that the figure's legs were unprotected. He shot at them twice with his shotgun, tearing apart Kelly's hip and thigh. The outlaw staggered, then collapsed against a fallen tree and moaned, "I'm done, I'm done".[107] Steele went to disarm him, but Kelly fired once more, blowing the sergeant's hat off and burning the side of his face.[109] Several others assisted Steele in removing the armour, and expressed shock upon discovering that it was Kelly. He became quiet, shot in the left foot, left leg, right hand, left arm and twice in the region of the groin, although no bullet had penetrated his armour. He was carried to the railway station, placed in a guard's van and then taken to the stationmaster's office, where a doctor dressed his wounds.[110][111]

In the meantime the siege continued. The female hostages confirmed that Dan and Hart were still alive in the hotel. They kept shooting from the rear of the building during the morning. At 10 am, a white flag or handkerchief was held out at the front door, and immediately afterwards about 30 male hostages emerged, while Dan and Hart defended the back door. The police ordered the hostages to lie down and were checked, one by one. Two of hostages were arrested for being known Kelly sympathisers.[110]

Fire and aftermath

By afternoon, Dan and Hart had ceased shooting. Unwilling to allow his men to storm the hotel, Superintendent Sadleir telegraphed to Melbourne for an artillery cannon to be sent up by special train to obliterate the outlaws. A 12-pounder Armstrong gun made it as far as Seymour when Sadleir decided to set fire to the hotel instead, and received permission from the Chief Secretary, Robert Ramsay. Under cover of fire, Senior Constable Charles Johnson, of Violet Town, placed a bundle of burning straw at the hotel's west side. Kate Kelly, Ned and Dan's sister, appeared on the scene around this time. She endeavoured to make way to her brothers, but the police ordered her to stop.[112]

A light westerly wind carried the flames into the hotel and it rapidly caught alight. Matthew Gibney, a priest from Western Australia, entered the burning structure in an attempt to rescue anyone inside.[113] He discovered the bodies of Dan and Hart, who he surmised had committed suicide. Whether they died in a suicide pact, or by other means, remains a mystery.[114] Caught hours earlier in police crossfire, hostage Martin Cherry, an old platelayer of the district, was found dying from a groin wound and promptly taken outside where Gibney gave him the last sacrament. Cherry succumbed within half an hour.[110][115] Another hostage, quarryman George Metcalf, was shot in the face, and died from the wound several months later. While he claimed it was an injury from police fire, more recent research indicates that Ned accidentally shot him the day prior to the siege.[116]

During the siege, John Jones, the 13-year-old son of the hotel's landlady, was shot in the hip by police crossfire,[117] dying the following day at Wangaratta Hospital. His elder sister, Jane, received a head wound during the siege from a stray bullet, and later died from a lung infection that her mother believed was hastened by the injury,[118] bringing the civilian death toll to four. Another three civilians were wounded by police fire: Charles Rawlins, a volunteer with the police; Michael Reardon, son of the line-repairer who tore up the tracks;[119] and Bridget Reardon, Michael's baby sister.[120] An Aboriginal tracker also had a narrow escape with a bushranger's bullet grazing his forehead.[112] Superintendent Hare retired from the force following the shootout, and, owing to his bullet wound, received an additional allowance of £100 per annum. He was appointed a Police Magistrate.

All that remained standing of the hotel was the lamp-post and the signboard.[110] Byrne's body was strung up in Benalla as a curiosity. His friends asked for the body, but the police instead secretly interred it at night in an unmarked grave in Benalla Cemetery.[121] The charred remains of Dan and Hart were taken to Greta and buried by their families in unmarked graves in the local cemetery, 30 km (19 mi) east of Benalla.[122]

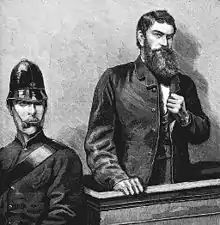

Trial and execution

Kelly survived to stand trial on 19 October 1880 in Melbourne before Sir Redmond Barry, the judge who had earlier sentenced Kelly's mother to three years in prison for the attempted murder of Fitzpatrick.[123] Mr Smyth and Mr Chomley appeared for the crown and Mr Bindon for the prisoner.[124] The trial was adjourned to 28 October, when Kelly was presented on the charge murdering Constable Lonigan and Const. Scanlan. He was never charged with the murder of Sgt. Kennedy. He was charged with the various bank robberies, the murder of Sherritt, resisting arrest at Glenrowan and with a long list of minor charges.[125] He was convicted of the wilful murder of Lonigan and sentenced to death by hanging. After handing down the sentence, Barry concluded with the customary words, "May God have mercy on your soul", to which Kelly replied, "I will go a little further than that, and say I will see you there where I go".[126]

On 3 November, the Executive Council of Victoria decided that Kelly was to be hanged eight days later, 11 November, at the Old Melbourne Gaol.[127] In the week leading up to the execution, thousands turned out at street rallies across Melbourne demanding a reprieve for Kelly, and on 8 November, a petition for clemency with over 32,000 signatures, some of which were of a suspicious nature, was presented to the governor's private secretary. The Executive Council announced soon after that the hanging would proceed as scheduled.[128]

The day before his execution, Kelly had his photographic portrait taken as a keepsake for his family, and he was granted farewell interviews with relatives. His mother's last words to him were reported to be, "Mind you die like a Kelly".[129] The following morning, John Castieau, the Governor of the Gaol, informed Kelly that the hour of execution had been fixed at 10 am. Kelly's leg-irons were removed, and after a short time he was marched out. He was submissive on the way, and when passing the gaol's flower beds, remarked, "What a nice little garden", but said nothing further until reaching the Press room, where he remained until the arrival of chaplain Dean Donaghy. Accounts differ about Kelly's last words. Some newspaper reporters wrote that it was "Such is life", while other newspapers recorded that this was his response when Castieau told him of the intended hour of his execution, earlier that day.[130] The Argus wrote that Kelly's last words were, "Ah, well, I suppose it has come to this", as the rope was placed round his neck.[131] According to another account, Kelly intended to make a speech, but "made no audible sound".[130] The warden later wrote that Kelly, when prompted to say his last words, mumbled something indiscernible.[130]

Armour

Aftermath and lessons

In March 1881, the Victorian Government approved a Royal Commission into the conduct of the Victoria Police during the Kelly Outbreak.[132] Over the next six months, the commission, chaired by Francis Longmore, held 66 meetings, examined 62 witnesses, and visited towns throughout "Kelly Country". While its report found that the police had acted properly in relation to the criminality of the Kellys, it exposed widespread corruption and shattered a number of police careers in addition to that of Chief Commissioner Frederick Standish.[133] Numerous other officers, including senior staff, were reprimanded, demoted or suspended. It concluded with a list of 36 recommendations for reform.[123] Kelly hoped that his death would lead to an investigation into police conduct, and although the report did not exonerate him or his gang, its findings were said to strip the authorities "of what scanty rags of reputation the Kellys had left them."[134]

The £8,000 reward money was divided among various claimants with £6,000 going to members of the Victoria Police, Superintendent Hare receiving the lion's share of £800. Curnow complained about his payout of £550, and the following year it was upgraded to £1,000. Seven Aboriginal trackers involved in the siege were each awarded £50, but their money was given to the Victorian and Queensland governments for safekeeping, the Reward Board's argument being, "It would not be desirable to place any considerable sum of money in the hands of persons unable to uses it."[135]

Writers such as Boxhall (The Story of Australian Bushrangers, 1899) and Henry Giles Turner (History of the Colony of Victoria, 1904) describe the Kelly Outbreak as simply a spate of criminality. Two of those involved, Superintendents Hare and Sadleir,[136] and later, in the late 20th century, Penzig (1988) wrote legitimising narratives about law and order and moral justification.

Others, commencing with Kenneally (1929), McQuilton (1979) and Jones (1995), perceived the Kelly Outbreak and the problems of Victoria's Land Selection Acts post-1860s as interlinked. McQuilton identified Kelly as the "social bandit" who was caught up in unresolved social contradictions—that is, the selector–squatter conflicts over land—and that Kelly gave the selectors the leadership they lacked. O'Brien (1999) identified a leaderless rural malaise in Northeastern Victoria as early as 1872–73, around land, policing and the Impounding Act.

Though the Kelly Gang was destroyed in 1880, for almost seven years a serious threat of a second outbreak existed because of major problems around land settlement and selection.

McQuilton suggested that two police officers involved in the pursuit of the Kelly Gang – John Sadleir,[137] author of Recollections of a Victorian Police Officer, and Inspector W.B. Montford – averted the Second Outbreak by coming to understand that the unresolved social contradiction in Northeastern Victoria was about land, not crime, and by their good work in aiding small selectors. This scenario was disputed by Dr Doug Morrissey in his book Ned Kelly, Selectors, Squatters and Stock Thieves. (2018)

Kelly's mother outlived him by several decades and died, aged 95, on 27 March 1923.[138]

Remains and graves

In line with the practice of the day, no records were kept regarding the disposal of an executed person's remains. Kelly was buried in the "old men's yard", just inside the walls of Old Melbourne Gaol.[139]

Dissection

A newspaper reported that Kelly's body was dissected by medical students who removed his head and organs for study.[140] Dissection outside of a coronial enquiry was illegal. Public outrage at the rumour raised real fears of public disorder, leading the commissioner of police to write to the gaol's governor, who denied that a dissection had taken place.[141] (Saw cuts on a piece of his occipital bone recovered in 2011 confirm that a dissection had been done.)

Grave robbery

In 1929, Melbourne Gaol was closed for routine demolition, and the bodies in its graveyard were uncovered during the demolition works. During the recovery of the bodies, spectators and workers stole skeletal parts and skulls from a number of graves, including one marked with an arrow and the initials "E. K."[142] in the belief they belonged to Ned Kelly.[143] The E.K. marked grave was situated by itself, and on the opposite side of the yard where the rest of the graveyard was situated.[144] The site foreman, Harry Franklin, retrieved the skull from the E.K. marked grave and gave it to the police. As no provision had been made for the disposal of the remains, Franklin had the bodies reburied in Pentridge prison at his own expense.[141] The skull from the E.K. marked grave, which had been stored at the Victorian Penal Department was taken to Canberra for research by the first director of the Australian Institute of Anatomy (Sir Colin Mackenzie) in 1934. For a period of time it was lost, but was later found while cleaning out an old safe in 1952.[145] In 1971, the Institute gave it to the National Trust.

Theft of skull

In 1972 the skull was put on display at the Old Melbourne Gaol until it was stolen on 12 December 1978.[146] An investigation in 2010 proved that the displayed skull was in fact the one recovered in April 1929.[141]

Historical and forensic investigation of remains

On 9 March 2008, it was announced that Australian archaeologists believed they had found Kelly's grave on the site of Pentridge Prison.[147] The bones were uncovered at a mass grave and Kelly's are among those of 32 felons who had been executed by hanging. Jeremy Smith, a senior archaeologist with Heritage Victoria, said that "We believe we have conclusively found the burial site but that is very different from finding the remains". Ellen Hollow, Kelly's then 62-year-old grand-niece, offered to supply her own DNA to help identify Kelly's bones.[148]

On the anniversary of Kelly's hanging, 11 November 2009, Tom Baxter handed the skull in his possession to police and it was historically and forensically tested along with the Pentridge remains. The skull was compared to a cast of the skull that had been stolen from the Old Melbourne Gaol in 1978 and proved to be a match. The skull was then compared to that in a newspaper photograph of worker Alex Talbot holding the skull recovered in 1929 which showed a close resemblance. Talbot was known to have taken a tooth from the skull as a souvenir and a media campaign to find the whereabouts of the tooth led to Talbot's grandson coming forward. The tooth was found to belong to the skull confirming it was indeed the skull recovered in 1929. In 2004, before the skull was handed to police, a cast of the skull was made and compared to the death masks of those executed at Old Melbourne Gaol which eliminated all but two. The two were those of Kelly and Ernest Knox, who had been executed in March 1894 (headstone marked E.K., 19–3–94) and buried near Frederick Deeming (headstone marked with the initials A.W. and a D underneath). In April 1929, the skulls of the E.K. marked grave (which was thought at the time to belong to Kelly) and Frederick Deeming were looted from the excavated graves.[149] The death mask of Knox and a facial reconstruction of a cast of the skull were a close match.[150]

In 2010 and 2011, the Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine performed a series of craniofacial super-imposition, CT scanning, anthropology and DNA tests on the skull recovered from the E.K. marked grave and concluded it was not Kelly's.[151] In 2014, the remains of Frederick Deeming's brother was exhumed from Bebington cemetery and tissue samples were obtained from the femur bone. A DNA profile was successfully obtained from the samples and compared with a DNA profile that had been previously obtained from the skull that was stolen from the Old Melbourne Gaol. The DNA profiles did not match, conclusively proving that the skull is not Deeming's.[152][153] It is now accepted that the skull recovered in 1929 and later displayed in the Old Melbourne Gaol was not Kelly's or Deeming's.[141]

Forensic pathologists also examined the bones from Pentridge, which were much decayed and jumbled with the remains of others, making identification difficult. The collar bone was found to be the only bone that had survived in all the skeletons and these were all DNA tested against that of Leigh Oliver. A match to Kelly was found and the associated skeleton turned out to be one of the most complete. Kelly's remains were additionally identified by partially healed right foot, right knee and left elbow injuries matching those caused by the bullet wounds at Glenrowan as recorded by the gaol's surgeon in 1880 and by the fact that his head was missing, likely removed for phrenological study. A section from the back of a skull (the occipital) was recovered from the grave that bore saw cuts that matched those present on several neck vertebrae indicating that the skull section belonged to the skeleton and that an illegal dissection had been performed.[141]