Neurosarcoidosis

Neurosarcoidosis (sometimes shortened to neurosarcoid) refers to a type of sarcoidosis, a condition of unknown cause featuring granulomas in various tissues, in this type involving the central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). Neurosarcoidosis can have many manifestations, but abnormalities of the cranial nerves (a group of twelve nerves supplying the head and neck area) are the most common. It may develop acutely, subacutely, and chronically. Approximately 5–10 percent of people with sarcoidosis of other organs (e.g. lung) develop central nervous system involvement. Only 1 percent of people with sarcoidosis will have neurosarcoidosis alone without involvement of any other organs. Diagnosis can be difficult, with no test apart from biopsy achieving a high accuracy rate. Treatment is with immunosuppression.[1] The first case of sarcoidosis involving the nervous system was reported in 1905.[2][3]

| Neurosarcoidosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Besnier-Boeck-Schaumann disease |

| |

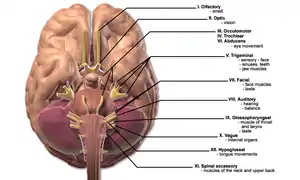

| This condition affects the cranial nerves | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

| Diagnostic method | Biopsy |

| Treatment | immunosuppression |

Signs and symptoms

Neurological

Abnormalities of the cranial nerves are present in 50–70 percent of cases. The most common abnormality is involvement of the facial nerve, which may lead to reduced power on one or both sides of the face (65 percent resp 35 percent of all cranial nerve cases), followed by reduction in visual perception due to optic nerve involvement. Rarer symptoms are double vision (oculomotor nerve, trochlear nerve or abducens nerve), decreased sensation of the face (trigeminal nerve), hearing loss or vertigo (vestibulocochlear nerve), swallowing problems (glossopharyngeal nerve) and weakness of the shoulder muscles (accessory nerve) or the tongue (hypoglossal nerve). Visual problems may also be the result of papilledema (swelling of the optic disc) due to obstruction by granulomas of the normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulation.[1]

Seizures (mostly of the tonic-clonic/"grand mal" type) are present in about 15 percent and may be the presenting phenomenon in 10 percent.[1]

Meningitis (inflammation of the lining of the brain) occurs in 3–26 percent of cases. Symptoms may include headache and nuchal rigidity (being unable to bend the head forward). It may be acute or chronic.[1]

Accumulation of granulomas in particular areas of the brain can lead to abnormalities in the function of that area. For instance, involvement of the internal capsule would lead to weakness in one or two limbs on one side of the body. If the granulomas are large, they can exert a mass effect and cause headache and increase the risk of seizures. Obstruction of the flow of cerebrospinal fluid, too, can cause headaches, visual symptoms (as mentioned above) and other features of raised intracranial pressure and hydrocephalus.[1]

Involvement of the spinal cord is rare, but can lead to abnormal sensation or weakness in one or more limbs, or cauda equina symptoms (incontinence to urine or stool, decreased sensation in the buttocks).[1]

Endocrine

Granulomas in the pituitary gland, which produces numerous hormones, is rare but leads to any of the symptoms of hypopituitarism: amenorrhoea (cessation of the menstrual cycle), diabetes insipidus (dehydration due to inability to concentrate the urine), hypothyroidism (decreased activity of the thyroid) or hypocortisolism (deficiency of cortisol).[1]

Mental and other

Psychiatric problems occur in 20 percent of cases; many different disorders have been reported, e.g. depression and psychosis. Peripheral neuropathy has been reported in up to 15 percent of cases of neurosarcoidosis.[1]

Other symptoms due to sarcoidosis of other organs may be uveitis (inflammation of the uveal layer in the eye), dyspnoea (shortness of breath), arthralgia (joint pains), lupus pernio (a red skin rash, usually of the face), erythema nodosum (red skin lumps, usually on the shins), and symptoms of liver involvement (jaundice) or heart involvement (heart failure).[1]

Pathophysiology

Sarcoidosis is a disease of unknown cause that leads to the development of granulomas in various organs. While the lungs are typically involved, other organs may equally be affected. Some subforms of sarcoidosis, such as Löfgren syndrome, may have a particular precipitant and have a specific course. It is unknown which characteristics predispose sarcoidosis patients to brain or spinal cord involvement.[1]

Diagnosis

Right image: MRI brain with contrast showing near resolution of enhancement after treatment.

The diagnosis of neurosarcoidosis often is difficult. Definitive diagnosis can only be made by biopsy (surgically removing a tissue sample). Because of the risks associated with brain biopsies, they are avoided as much as possible. Other investigations that may be performed in any of the symptoms mentioned above are computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain, lumbar puncture, electroencephalography (EEG) and evoked potential (EP) studies. If the diagnosis of sarcoidosis is suspected, typical X-ray or CT appearances of the chest may make the diagnosis more likely; elevations in angiotensin-converting enzyme and calcium in the blood, too, make sarcoidosis more likely. In the past, the Kveim test was used to diagnose sarcoidosis. This now obsolete test had a high (85 percent) sensitivity, but required spleen tissue of a known sarcoidosis patient, an extract of which was injected into the skin of a suspected case.[1]

Only biopsy of suspicious lesions in the brain or elsewhere is considered useful for a definitive diagnosis of neurosarcoid. This would demonstrate granulomas (collections of inflammatory cells) rich in epithelioid cells and surrounded by other immune system cells (e.g. plasma cells, mast cells). Biopsy may be performed to distinguish mass lesions from tumours (e.g. gliomas).[1]

MRI with gadolinium enhancement is the most useful neuroimaging test. This may show enhancement of the pia mater or white matter lesions that may resemble the lesions seen in multiple sclerosis.[1]

Lumbar puncture may demonstrate raised protein level, pleiocytosis (i.e. increased presence of both lymphocytes and neutrophil granulocytes) and oligoclonal bands. Various other tests (e.g. ACE level in CSF) have little added value.[1]

Criteria

Some recent papers propose to classify neurosarcoidosis by likelihood:[1]

- Definite neurosarcoidosis can only be diagnosed by plausible symptoms, a positive biopsy and no other possible causes for the symptoms

- Probable neurosarcoidosis can be diagnosed if the symptoms are suggestive, there is evidence of central nervous system inflammation (e.g. CSF and MRI), and other diagnoses have been excluded. A diagnosis of systemic sarcoidosis is not essential.

- Possible neurosarcoidosis may be diagnosed if there are symptoms not due to other conditions but other criteria are not fulfilled.

Treatment

Neurosarcoidosis, once confirmed, is generally treated with glucocorticoids such as prednisolone. If this is effective, the dose may gradually be reduced (although many patients need to remain on steroids long-term, frequently leading to side-effects such as diabetes or osteoporosis). Methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, cyclophosphamide, pentoxifylline, thalidomide and infliximab have been reported to be effective in small studies. In patients unresponsive to medical treatment, radiotherapy may be required. If the granulomatous tissue causes obstruction or mass effect, neurosurgical intervention is sometimes necessary. Seizures can be prevented with anticonvulsants, and psychiatric phenomena may be treated with medication usually employed in these situations.[1]

Prognosis

Of the phenomena occurring in neurosarcoid, only facial nerve involvement is known to have a good prognosis and good response to treatment. Long-term treatment is usually necessary for all other phenomena.[1] The mortality rate is estimated at 10 percent[4]

Epidemiology

Sarcoidosis has a prevalence of 40 per 100,000 in the general population. However, though those with the GG genotype at rs1049550 in the ANXA11 gene were found to have 1.5–2.5 times higher odds of sarcoidosis compared to those with the AG genotype, while those with the AA genotype had about 1.6 times lower odds.[5][6] Furthermore, those with Common Variable Immunodeficiency (CVID) may be at even higher risk. One study of 80 CVID patients found eight of these had sarcoidosis, suggesting as high a prevalence in CVID populations as one in 10.[7] Given that less than 10 percent of those with sarcoidosis will have neurological involvement, and possibly later on in their disease course, neurosarcoidosis has a prevalence of less than four per 100,000.[1]

Sarcoidosis most commonly affects young adults of both sexes, although studies have reported more cases in females. Incidence is highest for individuals younger than 40 and peaks in the age-group from 20 to 29 years; a second peak is observed for women over 50.[8][9]

Sarcoidosis occurs throughout the world in all races with an average incidence of 16.5/100,000 in men and 19/100,000 in women. The disease is most prevalent in Northern European countries and the highest annual incidence of 60/100,000 is found in Sweden and Iceland. In the United States sarcoidosis is more common in people of African descent than Caucasians, with annual incidence reported as 35.5 and 10.9/100,000, respectively.[10] Sarcoidosis is less commonly reported in South America, Spain, India, Canada, and the Philippines. There may be a higher susceptibility to sarcoidosis in those with coeliac disease. An association between the two disorders has been suggested.[11]

The differing incidence across the world may be at least partially attributable to the lack of screening programs in certain regions of the world and the overshadowing presence of other granulomatous diseases, such as tuberculosis, that may interfere with the diagnosis of sarcoidosis where they are prevalent.[9] There may also be differences in the severity of the disease between people of different ethnicities. Several studies suggest that the presentation in people of African origin may be more severe and disseminated than for Caucasians, who are more likely to have asymptomatic disease.[12]

Manifestation appears to be slightly different according to race and sex. Erythema nodosum is far more common in men than in women and in Caucasians than in other races. In Japanese patients, ophthalmologic and cardiac involvement are more common than in other races.[8]

Sarcoidosis is one of the few pulmonary diseases with a higher prevalence in non-smokers.[13]

Notable cases

The American television personality and actress Karen Duffy wrote "Model Patient: My Life As an Incurable Wise-Ass" on her experiences with neurosarcoidosis.[14]

References

- Joseph FG, Scolding NJ (2007). "Sarcoidosis of the nervous system". Practical Neurology. 7 (4): 234–44. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.124263. PMID 17636138. S2CID 9658767.

- Colover J (1948). "Sarcoidosis with involvement of the nervous system". Brain. 71 (Pt. 4): 451–75. doi:10.1093/brain/71.4.451. PMID 18124739.

- Burns TM (August 2003). "Neurosarcoidosis". Archives of Neurology. 60 (8): 1166–8. doi:10.1001/archneur.60.8.1166. PMID 12925378.

- Hoitsma E, Sharma OP (2005). "Neurosarcoidosis". In Drent M, Costabel U (eds.). Sarcoidosis (Monograph). UK: European Respiratory Society. pp. 164–187. ISBN 1-90409-737-5.

- Li, Y.; Pabst, S.; Kubisch, C.; Grohé, C.; Wollnik, B. (2010). "First independent replication study confirms the strong genetic association of ANXA11 with sarcoidosis". Thorax. 65 (10): 939–940. doi:10.1136/thx.2010.138743. PMID 20805159.

- Hofmann, S.; Franke, A.; Fischer, A.; Jacobs, G.; Nothnagel, M.; Gaede, K. I.; Schürmann, M.; Müller-Quernheim, J.; Krawczak, M.; Rosenstiel, P.; Schreiber, S. (2008). "Genome-wide association study identifies ANXA11 as a new susceptibility locus for sarcoidosis". Nature Genetics. 40 (9): 1103–1106. doi:10.1038/ng.198. PMID 19165924. S2CID 205344714.

- Fasano, M. B.; Sullivan, K. E.; Sarpong, S. B.; Wood, R. A.; Jones, S. M.; Johns, C. J.; Lederman, H. M.; Bykowsky, M. J.; Greene, J. M.; Winkelstein, J. A. (1996). "Sarcoidosis and common variable immunodeficiency. Report of 8 cases and review of the literature". Medicine. 75 (5): 251–261. doi:10.1097/00005792-199609000-00002. PMID 8862347.

- Nunes H, Bouvry D, Soler P, Valeyre D (2007). "Sarcoidosis". Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2: 46. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-2-46. PMC 2169207. PMID 18021432.

- Syed J, Myers R (January 2004). "Sarcoid heart disease". Can J Cardiol. 20 (1): 89–93. PMID 14968147.

- Henke, CE.; Henke, G.; Elveback, LR.; Beard, CM.; Ballard, DJ.; Kurland, LT. (May 1986). "The epidemiology of sarcoidosis in Rochester, Minnesota: a population-based study of incidence and survival". Am J Epidemiol. 123 (5): 840–5. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114313. PMID 3962966.

- Rutherford RM, Brutsche MH, Kearns M, Bourke M, Stevens F, Gilmartin JJ (September 2004). "Prevalence of coeliac disease in patients with sarcoidosis". Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 16 (9): 911–5. doi:10.1097/00042737-200409000-00016. PMID 15316417. S2CID 24306517.

- "Statement on sarcoidosis. Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the World Association of Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders (WASOG) adopted by the ATS Board of Directors and by the ERS Executive Committee, February 1999". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 160 (2): 736–755. 1999. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.2.ats4-99. PMID 10430755.

- Warren, C. P. (1977). "Extrinsic allergic alveolitis: a disease commoner in non-smokers" (PDF). Thorax. 32 (5): 567–569. doi:10.1136/thx.32.5.567. PMC 470791. PMID 594937.

- Duffy, Karen Grover (2001). Model Patient : My Life As an Incurable Wise-Ass. New York, NY: Perennial. ISBN 0-06-095727-1.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |