Lymphocyte

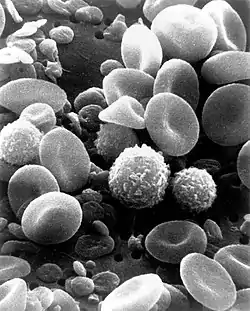

A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell in the vertebrate immune system.[1] Lymphocytes include natural killer cells (which function in cell-mediated, cytotoxic innate immunity), T cells (for cell-mediated, cytotoxic adaptive immunity), and B cells (for humoral, antibody-driven adaptive immunity).[2][3] They are the main type of cell found in lymph, which prompted the name "lymphocyte".[4]

| Lymphocyte | |

|---|---|

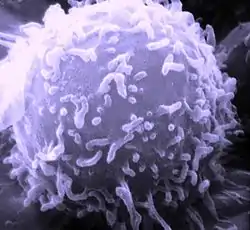

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of a single human lymphocyte | |

| Details | |

| System | Immune system |

| Function | White blood cell |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D008214 |

| TH | H2.00.04.1.02002 |

| FMA | 62863 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

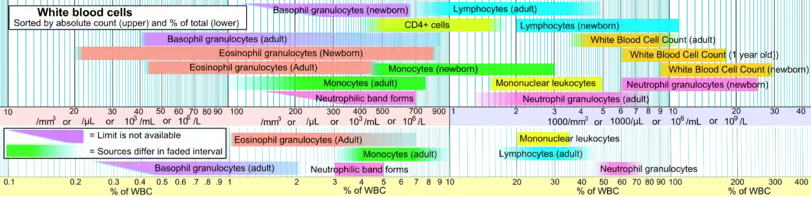

Lymphocytes make up between 18% and 42% of circulating leukocytes.[2]

Types

The three major types of lymphocyte are T cells, B cells and natural killer (NK) cells.[2] Lymphocytes can be identified by their large nucleus.

T cells and B cells

T cells (thymus cells) and B cells (bone marrow- or bursa-derived cells[lower-alpha 1]) are the major cellular components of the adaptive immune response. T cells are involved in cell-mediated immunity, whereas B cells are primarily responsible for humoral immunity (relating to antibodies). The function of T cells and B cells is to recognize specific "non-self" antigens, during a process known as antigen presentation. Once they have identified an invader, the cells generate specific responses that are tailored maximally to eliminate specific pathogens or pathogen-infected cells. B cells respond to pathogens by producing large quantities of antibodies which then neutralize foreign objects like bacteria and viruses. In response to pathogens some T cells, called T helper cells, produce cytokines that direct the immune response, while other T cells, called cytotoxic T cells, produce toxic granules that contain powerful enzymes which induce the death of pathogen-infected cells. Following activation, B cells and T cells leave a lasting legacy of the antigens they have encountered, in the form of memory cells. Throughout the lifetime of an animal, these memory cells will "remember" each specific pathogen encountered, and are able to mount a strong and rapid response if the same pathogen is detected again; this is known as acquired immunity.

Natural killer cells

NK cells are a part of the innate immune system and play a major role in defending the host from tumors and virally infected cells.[2] NK cells modulate the functions of other cells, including macrophages and T cells,[2] and distinguish infected cells and tumors from normal and uninfected cells by recognizing changes of a surface molecule called MHC (major histocompatibility complex) class I. NK cells are activated in response to a family of cytokines called interferons. Activated NK cells release cytotoxic (cell-killing) granules which then destroy the altered cells.[6] They are named "natural killer cells" because they do not require prior activation in order to kill cells which are missing MHC class I.

X lymphocyte

The X lymphocyte is a reported cell type expressing both a B-cell receptor and T-cell receptor and is hypothesized to be implicated in type 1 diabetes.[7][8] Its existence as a cell type has been challenged due to irreproducibility at multiple institutions.[9][10]

Development

Mammalian stem cells differentiate into several kinds of blood cell within the bone marrow.[11] This process is called haematopoiesis. All lymphocytes originate, during this process, from a common lymphoid progenitor before differentiating into their distinct lymphocyte types. The differentiation of lymphocytes follows various pathways in a hierarchical fashion as well as in a more plastic fashion. The formation of lymphocytes is known as lymphopoiesis. In mammals, B cells mature in the bone marrow, which is at the core of most bones.[12] In birds, B cells mature in the bursa of Fabricius, a lymphoid organ where they were first discovered by Chang and Glick,[12] (B for bursa) and not from bone marrow as commonly believed. T cells migrate to and mature in a distinct organ, called the thymus. Following maturation, the lymphocytes enter the circulation and peripheral lymphoid organs (e.g. the spleen and lymph nodes) where they survey for invading pathogens and/or tumor cells.

The lymphocytes involved in adaptive immunity (i.e. B and T cells) differentiate further after exposure to an antigen; they form effector and memory lymphocytes. Effector lymphocytes function to eliminate the antigen, either by releasing antibodies (in the case of B cells), cytotoxic granules (cytotoxic T cells) or by signaling to other cells of the immune system (helper T cells). Memory T cells remain in the peripheral tissues and circulation for an extended time ready to respond to the same antigen upon future exposure; they live weeks to several years, which is very long compared to other leukocytes.

Characteristics

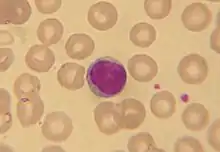

Microscopically, in a Wright's stained peripheral blood smear, a normal lymphocyte has a large, dark-staining nucleus with little to no eosinophilic cytoplasm. In normal situations, the coarse, dense nucleus of a lymphocyte is approximately the size of a red blood cell (about 7 μm in diameter).[11] Some lymphocytes show a clear perinuclear zone (or halo) around the nucleus or could exhibit a small clear zone to one side of the nucleus. Polyribosomes are a prominent feature in the lymphocytes and can be viewed with an electron microscope. The ribosomes are involved in protein synthesis, allowing the generation of large quantities of cytokines and immunoglobulins by these cells.

It is impossible to distinguish between T cells and B cells in a peripheral blood smear.[11] Normally, flow cytometry testing is used for specific lymphocyte population counts. This can be used to determine the percentage of lymphocytes that contain a particular combination of specific cell surface proteins, such as immunoglobulins or cluster of differentiation (CD) markers or that produce particular proteins (for example, cytokines using intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS)). In order to study the function of a lymphocyte by virtue of the proteins it generates, other scientific techniques like the ELISPOT or secretion assay techniques can be used.[6]

Typical recognition markers for lymphocytes[13] Class Function Proportion (median, 95% CI) Phenotypic marker(s) Natural killer cells Lysis of virally infected cells and tumour cells 7% (2–13%) CD16 CD56 but not CD3 T helper cells Release cytokines and growth factors that regulate other immune cells 46% (28–59%) TCRαβ, CD3 and CD4 Cytotoxic T cells Lysis of virally infected cells, tumour cells and allografts 19% (13–32%) TCRαβ, CD3 and CD8 Gamma delta T cells Immunoregulation and cytotoxicity 5% (2–8%) TCRγδ and CD3 B cells Secretion of antibodies 23% (18–47%) MHC class II, CD19 and CD20

In the circulatory system, they move from lymph node to lymph node.[1][3] This contrasts with macrophages, which are rather stationary in the nodes.

Lymphocytes and disease

A lymphocyte count is usually part of a peripheral complete blood cell count and is expressed as the percentage of lymphocytes to the total number of white blood cells counted.

A general increase in the number of lymphocytes is known as lymphocytosis,[14] whereas a decrease is known as lymphocytopenia.

High

An increase in lymphocyte concentration is usually a sign of a viral infection (in some rare case, leukemias are found through an abnormally raised lymphocyte count in an otherwise normal person).[14][15] A high lymphocyte count with a low neutrophil count might be caused by lymphoma. Pertussis toxin (PTx) of Bordetella pertussis, formerly known as lymphocytosis-promoting factor, causes a decrease in the entry of lymphocytes into lymph nodes, which can lead to a condition known as lymphocytosis, with a complete lymphocyte count of over 4000 per μl in adults or over 8000 per μl in children. This is unique in that many bacterial infections illustrate neutrophil-predominance instead.

Low

A low normal to low absolute lymphocyte concentration is associated with increased rates of infection after surgery or trauma.[16]

One basis for low T cell lymphocytes occurs when the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infects and destroys T cells (specifically, the CD4+ subgroup of T lymphocytes, which become helper T cells).[17] Without the key defense that these T cells provide, the body becomes susceptible to opportunistic infections that otherwise would not affect healthy people. The extent of HIV progression is typically determined by measuring the percentage of CD4+ T cells in the patient's blood – HIV ultimately progresses to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). The effects of other viruses or lymphocyte disorders can also often be estimated by counting the numbers of lymphocytes present in the blood.

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

In some cancers, such as melanoma and colorectal cancer, lymphocytes can migrate into and attack the tumor. This can sometimes lead to regression of the primary tumor.

Lymphocyte-variant hypereosinophilia

Blood content

History

See also

- Addressin

- Anergy

- Complete blood count

- Cytotoxicity

- Human leukocyte antigen

- Innate lymphoid cell

- Lymphocystivirus

- Lymphoproliferative disorders

- Reactive lymphocyte

- Secretion assay

- Trogocytosis

- All pages with titles containing Lymphocyte

- All pages with titles containing Lymphocytic

Notes

- The process of B-cell maturation was elucidated in birds and the B most likely means "bursa-derived" referring to the bursa of Fabricius.[5] However, in humans (who do not have that organ), the bone marrow makes B cells, and the B can serve as a reminder of bone marrow.

References

- Al-Shura, Anika Niambi (2020). "Lymphocytes". Advanced Hematology in Integrated Cardiovascular Chinese Medicine. Elsevier. pp. 41–46. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-817572-9.00007-0. ISBN 978-0-12-817572-9.

- Omman, Reeba A.; Kini, Ameet R. (2020). "Leukocyte development, kinetics, and functions". In Keohane, Elaine M.; Otto, Catherine N.; Walenga, Jeanine N. (eds.). Rodak's Hematology: Clinical Principles and Applications (6th ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. pp. 117–135. ISBN 978-0-323-53045-3.

- Cohn, Lauren; Hawrylowicz, Catherine; Ray, Anuradha (2014). "Biology of Lymphocytes". Middleton's Allergy: Principles and Practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 203–214. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-08593-9.00013-9. ISBN 9780323085939. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

A type of immune cell that is made in the bone marrow and is found in the blood and in lymph tissue. The two main types of lymphocytes are B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes. B lymphocytes make antibodies, and T lymphocytes help kill tumor cells and help control immune responses. A lymphocyte is a type of white blood cell.

- "B Cell". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- Janeway C, Travers P, Walport M, Shlomchik M (2001). Immunobiology (5th ed.). New York and London: Garland Science. ISBN 0-8153-4101-6.

- Ahmed, Rizwan; Omidian, Zahra; Giwa, Adebola; Cornwell, Benjamin; Majety, Neha; Bell, David R.; Lee, Sangyun; Zhang, Hao; Michels, Aaron; Desiderio, Stephen; Sadegh-Nasseri, Scheherazade (30 May 2019). "A Public BCR Present in a Unique Dual-Receptor-Expressing Lymphocyte from Type 1 Diabetes Patients Encodes a Potent T Cell Autoantigen". Cell. 177 (6): 1583–1599.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2019.05.007. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 31150624.

- "Newly Discovered Immune Cell Linked to Type 1 Diabetes". Johns Hopkins Medicine Newsroom. 30 May 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2020.

- Japp, Alberto (4 February 2021). "TCR+/BCR+ dual-expressing cells and their associated public BCR clonotype are not enriched in type 1 diabetes". Cell. 184 (3): 827–839. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.11.035. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Burel, Julie (13 May 2020). "The Challenge of Distinguishing Cell–Cell Complexes from Singlet Cells in Non-Imaging Flow Cytometry and Single-Cell Sorting". Cytometry Part A. 97 (11): 1127–1135. doi:10.1002/cyto.a.24027. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Abbas AK, Lichtman AH (2003). Cellular and Molecular Immunology (5th ed.). Saunders, Philadelphia. ISBN 0-7216-0008-5.

- Cooper MD (March 2015). "The early history of B cells". Nature Reviews. Immunology. 15 (3): 191–7. doi:10.1038/nri3801. PMID 25656707.

- Berrington JE, Barge D, Fenton AC, Cant AJ, Spickett GP (May 2005). "Lymphocyte subsets in term and significantly preterm UK infants in the first year of life analysed by single platform flow cytometry". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 140 (2): 289–92. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02767.x. PMC 1809375. PMID 15807853.

- "Lymphocytosis: Symptoms, Causes, Treatments". Cleveland Clinic. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Guilbert, Theresa W.; Gern, James E.; Lemanske, Robert F. (2010). "Infections and Asthma". Pediatric Allergy: Principles and Practice. Elsevier. pp. 363–376. doi:10.1016/b978-1-4377-0271-2.00035-3. ISBN 978-1-4377-0271-2. S2CID 78707217.

Lymphocytes are recruited into the upper and lower airways during the early stages of a viral respiratory infection, and it is presumed that these cells help to limit the extent of infection and to clear virus-infected epithelial cells.

- Clumeck, Nathan; de Wit, Stéphane (2010). "Prevention of opportunistic infections". Infectious Diseases. pp. 958–963. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-04579-7.00090-3. ISBN 9780323045797. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Wahed, Amer; Quesada, Andres; Dasgupta, Amitava (2020). "Benign white blood cell and platelet disorders". Hematology and Coagulation. Elsevier. pp. 77–87. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814964-5.00005-x. ISBN 978-0-12-814964-5.

Lymphocytopenia may also be acquired, for example, in patients with HIV infection.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lymphocytes. |

- Histology image: 01701ooa – Histology Learning System at Boston University

- "Cytotoxic T Lymphocyte". Cell Centered Database.

- "Overcoming the Rejection Factor: MUSC's First Organ Transplant". Waring Historical Library.

_diagram_en.svg.png.webp)