Olive ridley sea turtle

The olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea), also known commonly as the Pacific ridley sea turtle, is a species of turtle in the family Cheloniidae. The species is the second smallest[3] and most abundant of all sea turtles found in the world. Lepidochelys olivacea is found in warm and tropical waters, primarily in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, but also in the warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean.[4]

| Olive ridley sea turtle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Olive ridley sea turtle at Kélonia, an aquarium in Saint-Leu, Réunion | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Testudines |

| Suborder: | Cryptodira |

| Superfamily: | Chelonioidea |

| Family: | Cheloniidae |

| Genus: | Lepidochelys |

| Species: | L. olivacea |

| Binomial name | |

| Lepidochelys olivacea (Eschscholtz, 1829) | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

This turtle and the related Kemp's ridley turtle are best known for their unique mass nesting called arribada, where thousands of females come together on the same beach to lay eggs.[3]

Taxonomy

The olive ridley sea turtle may have been first described as Testudo mydas minor by Georg Adolf Suckow in 1798. It was later described and named Chelonia multiscutata by Heinrich Kuhl in 1820. Still later, it was described and named Chelonia olivacea by Johann Friedrich von Eschscholtz in 1829. The species was placed in the subgenus Lepidochelys by Leopold Fitzinger in 1843.[5] After Lepidochelys was elevated to full genus status, the species was called Lepidochelys olivacea by Charles Frédéric Girard in 1858. Because Eschscholtz was the first to propose the specific epithet olivacea, he is credited as the binomial authority or taxon author in the valid name Lepidochelys olivacea (Eschscholtz, 1829). The parentheses indicate that the species was originally described in a different genus.

The generic name, Lepidochelys, is derived from the Greek words lepidos, meaning scale, and chelys, which translates to turtle. This could possibly be a reference to the supernumerary costal scute counts characteristic of this genus.[6] The etymology of the English vernacular name "olive" is somewhat easier to resolve, as its carapace is olive green in color.[7] However, the origin of "ridley" is still somewhat unclear, perhaps derived from "riddle".[8] Lepidochelys is the only genus of sea turtles containing more than one extant species: L. olivacea and the closely related L. kempii (Kemp's ridley).[9]

Description

Growing to about 61 cm (2 ft) in carapace length (measured along the curve), the olive ridley sea turtle gets its common name from its olive-colored carapace, which is heart-shaped and rounded. Males and females grow to the same size; however, females have a slightly more rounded carapace as compared to males.[4] The heart-shaped carapace is characterized by four pairs of pore-bearing inframarginal scutes on the bridge, two pairs of prefrontals, and up to nine lateral scutes per side. L. olivacea is unique in that it can have variable and asymmetrical lateral scute counts, ranging from five to nine plates on each side, with six to eight being most commonly observed.[6] Each side of the carapace has 12–14 marginal scutes.

The carapace is flattened dorsally and highest anterior to the bridge. it has a medium-sized, broad head that appears triangular from above. The head's concave sides are most obvious on the upper part of the short snout. It has paddle-like fore limbs, each having two anterior claws. The upper parts are grayish green to olive in color, but sometimes appear reddish due to algae growing on the carapace. The bridge and hingeless plastron of an adult varies from greenish white in younger individuals to a creamy yellow in older specimens (maximum age is up to 50 years).[6][10]

Hatchlings are dark gray with a pale yolk scar, but appear all black when wet.[6] Carapace length of hatchlings ranges from 37 to 50 mm (1.5 to 2.0 in). A thin, white line borders the carapace, as well as the trailing edge of the fore and hind flippers.[10] Both hatchlings and juveniles have serrated posterior marginal scutes, which become smooth with age. Juveniles also have three dorsal keels; the central longitudinal keel gives younger turtles a serrated profile, which remains until sexual maturity is reached.[6]

The olive ridley sea turtle rarely weighs over 50 kg (110 lb). Adults studied in Oaxaca, Mexico,[6] ranged from 25 to 46 kg (55 to 101 lb); adult females weighed an average of 35.45 kg (78.2 lb) (n=58), while adult males weighed significantly less, averaging 33.00 kg (72.75 lb) (n=17). Hatchlings usually weigh between 12.0 and 23.3 g (0.42 and 0.82 oz).

Adults are sexually dimorphic. The mature male has a longer and thicker tail, which is used for copulation,[6] and the presence of enlarged and hooked claws on the male's front flippers allows it to grasp the female's carapace during copulation. The male also has a longer, more tapered carapace than the female, which has a rounded, dome-like carapace.[6] The male also has a more concave plastron, believed to be another adaptation for mating. The plastron of the male may also be softer than that of the female.[10]

Distribution

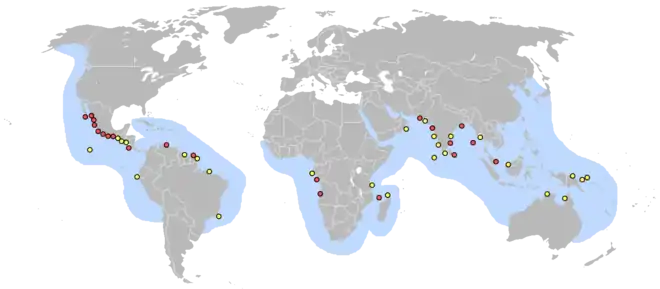

The olive ridley turtle has a circumtropical distribution, living in tropical and warm waters of the Pacific and Indian Oceans from India, Arabia, Japan, and Micronesia south to southern Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. In the Atlantic Ocean, it has been observed off the western coast of Africa and the coasts of northern Brazil, Suriname, Guyana, French Guiana, and Venezuela. Additionally, the olive ridley has been recorded in the Caribbean Sea as far north as Puerto Rico. A female was found alive on an Irish Sea beach on the Isle of Anglesey, Wales, in November 2016, giving this species its northernmost appearance. It was taken in by the nearby Anglesey Sea Zoo, while its health was assessed.[11] A juvenile female was found off the coast of Sussex in 2020.[12] The olive ridley is also found in the eastern Pacific Ocean from the Galápagos Islands and Chile north to the Gulf of California, and along the Pacific coast to at least Oregon. Migratory movements have been studied less intensely in olive ridleys than other species of marine turtles, but they are believed to use the coastal waters of over 80 countries.[13] Historically, this species has been widely regarded as the most abundant sea turtle in the world.[6] More than one million olive ridleys were commercially harvested off the coasts of Mexico in 1968 alone.[14]

The population of Pacific Mexico was estimated to be at least 10 million prior to the era of mass exploitation. More recently, the global population of annual nesting females has been reduced to about two million by 2004,[15] and was further reduced to 852,550 by 2008.[1][16] This indicated a dramatic decrease of 28 to 32% in the global population within only one generation (i.e., 20 years).[13]

Olive ridley sea turtles are considered the most abundant, yet globally they have declined by more than 30% from historic levels. These turtles are considered endangered because of their few remaining nesting sites in the world. The eastern Pacific turtles have been found to range from Baja California, Mexico, to Chile. Pacific olive ridleys nest around Costa Rica, Mexico, Nicaragua, and the northern Indian Ocean; the breeding colony in Mexico was listed as endangered in the US on July 28, 1978.[17]

Nesting grounds

.jpg.webp)

Olive ridley turtles are best known for their behavior of synchronized nesting in mass numbers, termed arribadas.[10] Females return to the same beach from where they hatched, to lay their eggs. They lay their eggs in conical nests about one and a half feet deep, which they laboriously dig with their hind flippers.[4] In the Indian Ocean, the majority of olive ridleys nest in two or three large groups near Gahirmatha in Odisha. The coast of Odisha in India is one the largest mass nesting site for the olive ridley, along with the coasts of Mexico and Costa Rica.[4] In 1991, over 600,000 turtles nested along the coast of Odisha in one week. Nesting occurs elsewhere along the Coromandel Coast and Sri Lanka, but in scattered locations. However, olive ridleys are considered a rarity in most areas of the Indian Ocean.[16]

They are also rare in the western and central Pacific, with known arribadas occurring only within the tropical eastern Pacific, in Central America and Mexico. In Costa Rica, they occur at Nancite and Ostional beaches. Two active arribadas are in Nicaragua, Chacocente and La Flor, with a small nesting ground in Pacific Panama. Historically, several arribadas were in Mexico, Playa Escobilla and Morro Ayuda in Oaxaca, and Ixtapilla in Michoacan are the three arribada beaches in the present .[16]

Although olive ridleys are famed for their arribadas, many of the nesting grounds can only support relatively small to moderate-sized aggregations (about 1,000 nesting females). The overall contribution and importance of these nesting beaches to the population may be underestimated by the scientific community.[6]

Foraging grounds

Some of the olive ridley's foraging grounds near southern California are contaminated due to sewage, agricultural runoff, pesticides, solvents, and industrial discharges. These contaminants have been shown to decrease the productivity of the benthic community, which negatively affects these turtles, which feed from these communities.[6] The increasing demand to build marinas and docks near Baja California and southern California are also negatively affecting the olive ridleys in these areas, where more oil and gasoline will be released into these sensitive habitats. Another threat to these turtles is power plants, which have documented juvenile and subadult turtles becoming entrained and entrapped within the saltwater cooling intake systems.[6]

Ecology and behavior

Reproduction

Mating is often assumed to occur in the vicinity of nesting beaches, but copulating pairs have been reported over 1,000 km from the nearest beach. Research from Costa Rica revealed the number of copulating pairs observed near the beach could not be responsible for the fertilization of the tens of thousands of gravid females, so a significant amount of mating is believed to have occurred elsewhere at other times of the year.[6]

The Gahirmatha Beach in Kendrapara district of Odisha (India), which is now a part of the Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary, is the largest breeding ground for these turtles. The Gahirmatha Marine Wildlife Sanctuary, which bounds the Bhitarkanika Wildlife Sanctuary to the east, was created in September 1997, and encompasses Gahirmatha Beach and an adjacent portion of the Bay of Bengal. Bhitarkanika mangroves were designated a Ramsar Wetland of International Importance in 2002. It is the world's largest known rookery of olive ridley sea turtles. Apart from Gahirmatha rookery, two other mass nesting beaches have been located, which are on the mouth of rivers Rushikulya and Devi. The spectacular site of mass congregation of olive ridley sea turtles for mating and nesting enthralls both the scientists and the nature lovers throughout the world.

Olive ridley sea turtles migrate in huge numbers from the beginning of November, every year, for mating and nesting along the coast of Orissa. Gahirmatha coast has the annual nesting figure between 100,000 and 500,000 each year. A decline in the population of these turtles has occurred in the recent past due to mass mortality. The olive ridley sea turtle has been listed on Schedule – I of the Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972 (amended 1991). The species is listed as vulnerable under IUCN.[1] The sea turtles are protected under the 'Migratory Species Convention' and Convention of International Trade on Wildlife Flora and Fauna (CITES). India is a signatory nation to all these conventions. The homing characteristics of the ridley sea turtles make them more prone to mass casualty. The voyage to the natal nesting beaches is the dooming factor for them. Since Gahirmatha coast serves as the natal nesting beach for millions of turtles, it has immense importance on turtle conservation.

Olive ridleys generally begin to aggregate near nesting beaches about two months before nesting season, although this may vary throughout their range. In the eastern Pacific, nesting occurs throughout the year, with peak nesting events (arribadas) occurring between September and December. Nesting beaches can be characterized as relatively flat, midbeach zone, and free of debris.[5] Beach fidelity is common, but not absolute. Nesting events are usually nocturnal, but diurnal nesting has been reported, especially during large arribadas.[6] Exact age of sexual maturity is unknown, but this can be somewhat inferred from data on minimum breeding size. For example, the average carapace length of nesting females (n = 251) at Playa Nancite, Costa Rica, was determined to be 63.3 cm, with the smallest recorded at 54.0 cm.[6] Females can lay up to three clutches per season, but most only lay one or two clutches.[10] The female remains near shore for the internesting period, which is about one month. Mean clutch size varies throughout its range and decreases with each nesting attempt.[16]

A mean clutch size of 116 (30–168 eggs) was observed in Suriname, while nesting females from the eastern Pacific were found to have an average of 105 (74–126 eggs).[10] The incubation period is usually between 45 and 51 days under natural conditions, but may extend to 70 days in poor weather conditions. Eggs incubated at temperatures of 31 to 32 °C produce only females; eggs incubated at 28 °C or less produce solely males; and incubation temperatures of 29 to 30 °C produce a mixed-sex clutch.[10] Hatching success can vary by beach and year, due to changing environmental conditions and rates of nest predation.

Habitat

Most observations are typically within 15 km of mainland shores in protected, relatively shallow marine waters (22–55 m deep).[10] Olive ridleys are occasionally found in open waters. The multiple habitats and geographical localities used by this species vary throughout its life cycle.[5] More research is needed to acquire data on and use of pelagic habitats.[6]

Feeding

The olive ridley is predominantly carnivorous, especially in immature stages of the life cycle. Animal prey consists of protochordates or invertebrates, which can be caught in shallow marine waters or estuarine habitats. Common prey items include jellyfish, tunicates, sea urchins, bryozoans, bivalves, snails, shrimp, crabs, rock lobsters, and sipunculid worms. Additionally, consumption of jellyfish and both adult fish (e.g. Sphoeroides) and fish eggs may be indicative of pelagic (open ocean) feeding.[10] The olive ridley is also known to feed on filamentous algae in areas devoid of other food sources. Captive studies have indicated some level of cannibalistic behavior in this species.[6]

Threats

Known predators of olive ridley eggs include raccoons, coyotes, feral dogs and pigs, opossums, coatimundi, caimans, ghost crabs, and the sunbeam snake.[10] Hatchlings are preyed upon as they travel across the beach to the water by vultures, frigate birds, crabs, raccoons, coyotes, iguanas, and snakes. In the water, hatchling predators most likely include oceanic fishes, sharks, and crocodiles. Adults have relatively few known predators, other than sharks, and killer whales are responsible for occasional attacks. On land, nesting females may be attacked by jaguars. Notably, the jaguar is the only cat with a strong enough bite to penetrate a sea turtle's shell, thought to be an evolutionary adaption from the Holocene extinction event. In observations of jaguar attacks, the cats consumed the neck muscles of the turtle and occasionally the flippers, but left the remainder of the turtle carcass for scavengers as most likely, despite the strength of its jaws, a jaguar still cannot easily penetrate an adult turtle's shell to reach the internal organs or other muscles. In recent years, increased predation on turtles by jaguars has been noted, perhaps due to habitat loss and fewer alternative food sources. Sea turtles are comparatively defenseless in this situation, as they cannot pull their heads into their shells like freshwater and terrestrial turtles.[6][18] Females are often plagued by mosquitos during nesting. Humans are still listed as the leading threat to L. olivacea, responsible for unsustainable egg collection, slaughtering nesting females on the beach, and direct harvesting adults at sea for commercial sale of both the meat and hides.[10]

Other major threats include mortality associated with boat collisions, and incidental takes in fisheries. Trawling, gill nets, ghost nests, longline fishing, and pot fishing have significantly affected olive ridley populations, as well as other species of marine turtles.[1][6] Between 1993 and 2003, more than 100,000 olive ridley turtles were reported dead in Odisha, India from fishery-related practices.[19] In addition, entanglement and ingestion of marine debris is listed as a major threat for this species. Coastal development, natural disasters, climate change, and other sources of beach erosion have also been cited as potential threats to nesting grounds.[6] Additionally, coastal development also threatens newly hatched turtles through the effects of light pollution.[20] Hatchlings which use light cues to orient themselves to the sea are now misled into moving towards land, and die from dehydration or exhaustion, or are killed on roads.

However, the greatest single cause of olive ridley egg loss results from arribadas, in which the density of nesting females is so high, previously laid nests are inadvertently dug up and destroyed by other nesting females.[6] In some cases, nests become cross-contaminated by bacteria or pathogens of rotting nests. For example, in Playa Nancite, Costa Rica, only 0.2% of the 11.5 million eggs produced in a single arribada successfully hatched. Although some of this loss resulted from predation and high tides, the majority was attributed to conspecifics unintentionally destroying existing nests. The extent to which arribadas contribute to the population status of olive ridleys has created debate among scientists. Many believe the massive reproductive output of these nesting events is critical to maintaining populations, while others maintain the traditional arribada beaches fall far short of their reproductive potential and are most likely not sustaining population levels.[6] In some areas, this debate eventually led to legalizing egg collection.

Economic importance

Historically, the olive ridley has been exploited for food, bait, oil, leather, and fertilizer. The meat is not considered a delicacy; the egg, however, is esteemed everywhere. Egg collection is illegal in most of the countries where olive ridleys nest, but these laws are rarely enforced. Harvesting eggs has the potential to contribute to local economies, so the unique practice of allowing a sustainable (legal) egg harvest has been attempted in several localities.[16] Numerous case studies have been conducted in regions of arribadas beaches to investigate and understand the socioeconomic, cultural, and political issues of egg collection. Of these, the legal egg harvest at Ostional, Costa Rica, has been viewed by many as both biologically sustainable and economically viable. Since egg collection became legal in 1987, local villagers have been able to harvest and sell around three million eggs annually. They are permitted to collect eggs during the first 36 hours of the nesting period, as many of these eggs would be destroyed by later nesting females. Over 27 million eggs are left unharvested, and villagers have played a large role in protecting these nests from predators, thereby increasing hatching success.[6]

Most participating households reported egg harvesting as their most important activity, and profits earned were superior to other forms of available employment, other than tourism. The price of Ostional eggs was intentionally kept low to discourage illegal collection of eggs from other beaches. The Ostional project retained more local profits than similar egg collection projects in Nicaragua,[16] but evaluating egg-harvesting projects such as this suffers from the short timeline and site specificity of findings. In most regions, illegal poaching of eggs is considered a major threat to olive ridley populations, thus the practice of allowing legal egg harvests continues to attract criticism from conservationists and sea turtle biologists. Plotkin's Biology and Conservation of Ridley Sea Turtles, particularly the chapter by Lisa Campbell titled "Understanding Human Use of Olive Ridleys", provides further research on the Ostional harvest (as well as other harvesting projects). Scott Drucker's documentary, Between the Harvest, offers a glimpse into this world and the debate surrounding it.

Conservation status

The olive ridley is classified as vulnerable according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), and is listed in Appendix I of CITES. These listings were largely responsible for halting the large-scale commercial exploitation and trade of olive ridley skins.[1] The Convention on Migratory Species and the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles have also provided olive ridleys with protection, leading to increased conservation and management for this marine turtle. National listings for this species range from endangered to threatened, yet enforcing these sanctions on a global scale has been unsuccessful for the most part. Conservation successes for the olive ridley have relied on well-coordinated national programs in combination with local communities and nongovernment organizations, which focused primarily on public outreach and education. Arribada management has also played a critical role in conserving olive ridleys.[16] Lastly, enforcing the use of turtle excluder devices in the shrimp-trawling industry has also proved effective in some areas.[1] Globally, the olive ridley continues to receive less conservation attention than its close relative, the Kemp's ridley (L. kempii). Also, many schools arrange trips for students to carry out the conservation project, especially in India.

Several projects worldwide seek to preserve the olive ridley sea turtle population. For example, in Nuevo Vallarta, Mexico, when the turtles come to the beach to lay their eggs, some of them are relocated to a hatchery, where they have a much better chance to survive. If the eggs were left on the beach, they would face many threats such as getting washed away with the tide or getting poached. Once the eggs hatch, the baby turtles are carried to the beach and released.

Another major project, in India involved in preserving the olive ridley sea turtle population was carried out in Chennai, where the Chennai wildlife team collected close to 10,000 eggs along the Marina coast, of which 8,834 hatchlings were successfully released into the sea in a phased manner.[21]

References

- Abreu-Grobois, A.; Plotkin, P. (2008). "Lepidochelys olivacea". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- Fritz, Uwe; Havaš, Peter (2007). "Checklist of Chelonians of the World" (PDF). Vertebrate Zoology. 57 (2): 169–170. ISSN 1864-5755. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2012. Alt URL

- "Olive ridley Turtle". Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- "Olive ridley Turtle". wwfindia.org.

- "Lepidochelys olivacea" at the Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- "Recovery Plan for U.S. Pacific Populations of the Olive Ridley Turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea)". Silver Spring, MD: National Marine Fisheries Service. 1998. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- Ellis, Richard (2003). The Empty Ocean: Plundering the World's Marine Life. Washington: Island Press. ISBN 1597265993.

- Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Lepidochelys olivacea, p. 221).

- "Marine Turtle Newsletter" – Harold A. Dundee

- Ernst, Carl H.; Barbour, Roger W.; Lovich, Jeffrey E. (1994). Turtles of the United States and Canada. Washington [u.a.]: Smithsonian Inst. Press. ISBN 1560983469.

- "Scan results 'good news' for health of stranded sea turtle", Retrieved on 26 January 2017.

- "Olive ridley turtle found injured off Seaford beach". BBC News. 19 January 2020. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- "Lepidochelys olivacea – Olive Ridley Turtle, Pacific Ridley Turtle". Species Profile and Threats Database. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- Carr, A. (March 1972). "Great Reptiles, Great Enigmas". Audubon. 74 (2): 24–35.

- Spotila, James R. (2004). Sea Turtles: a Complete Guide to their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 132. ISBN 0801880076.

- Pamela T. Plotkin, ed. (2007). Biology and Conservation of Ridley Sea Turtles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801886119.

- "Forging a Future for Pacific Sea Turtles" (PDF). Oceana. 2007. p. 6. Retrieved 16 April 2013.

- "Jaguar v. sea turtle: when land and marine conservation icons collide". news.mongabay.com.

- Shanker, K.; Ramadevi, J.; Choudhury, B. C.; Singh, L.; Aggarwal, R. K. (16 April 2004). "Phylogeography of olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) on the east coast of India: implications for conservation theory". Molecular Ecology. 13 (7): 1899–1909. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02195.x. PMID 15189212. S2CID 17524432.

- Karnad, Divya; Isvaran, Kavita; Kar, Chandrasekhar S.; Shanker, Kartik (1 October 2009). "Lighting the way: Towards reducing misorientation of olive ridley hatchlings due to artificial lighting at Rushikulya, India". Biological Conservation. 142 (10): 2083–2088. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2009.04.004.

- "Over 8000 turtle hatchlings released", Deccan Chronicle, Chennai, 23 May 2014. Retrieved on 23 May 2014.

Further reading

- Eschscholtz F (1829). Zoologischer Atlas, enthaltend Abbildungen und Beschreibungen neuer Thierarten, während des Flottcapitains von Kotzbue zweiter Reise um die Welt, auf der Russisch-Kaiserlichen Kriegsschlupp Predpriaetië in den Jahren 1823 — 1826. Erstes Heft. Berlin: G. Reimer. iv + 17 pp. + Plates I-V. (Chelonia olivacea, new species, pp. 3–4 + Plate III). (in German and Latin).

- Smith HM, Brodie ED Jr (1982). Reptiles of North America: A Guide to Field Identification. New York: Golden Press. 240 pp. ISBN 0-307-13666-3 (paperback), ISBN 0-307-47009-1 (hardcover). (Lepidochelys olivacea, pp. 36–37).

- Stebbins RC (2003). A Field Guide to Western Reptiles and Amphibians, Third Edition. The Peterson Field Guide Series. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company. xiii + 533 pp., 56 plates. ISBN 978-0-395-98272-3. (Lepidochelys olivacea, p. 259 + Plate 23).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lepidochelys olivacea. |

- NOAA Fisheries: Olive ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) webpage

- "Olive Ridley Project" webpage

- Photos of Olive ridley sea turtle on Sealife Collection