Ollanta Humala

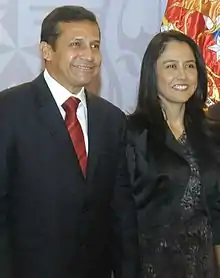

Ollanta Moisés Humala Tasso (Spanish pronunciation: [oˈʝanta uˈmala]; born 27 June 1962) is a Peruvian politician and former military officer who served as President of Peru from 2011 to 2016. A former army officer, Humala lost the 2006 presidential election and eventually won the 2011 presidential election in a run-off vote.[1] He was elected as President of Peru in the second round, defeating Keiko Fujimori.

The son of Isaac Humala, a labour lawyer, Humala entered the Peruvian Army in 1981. In the military he achieved the rank of Lieutenant Colonel; in 1991 he fought in the internal conflict against the Shining Path and three years later he participated in the Cenepa War against Ecuador. In October 2000, Humala attempted an unsuccessful coup d'etat by soldiers in the southern city of Tacna against President Alberto Fujimori during the dying days of his regime;[2] he was pardoned by the Peruvian Congress after the downfall of the Fujimori regime.

In 2005 he founded the Peruvian Nationalist Party and registered to run in the 2006 presidential election. The nomination was made under the Union for Peru ticket as the Nationalist party did not achieve its electoral inscription on time. He passed the first round of the elections, held on April 9, 2006, with 30.62% of the valid votes. A runoff was held on June 4 between Humala and Alan García of the Peruvian Aprista Party. Humala lost the run-off with 47.38% of the valid votes versus 52.62% for García. After his defeat, Humala remained an important figure within Peruvian politics.

In February 2016, amidst the Peruvian Presidential Race, a report from the Brazilian Federal Police implicated Humala as recipient of bribes from Odebrecht, a Brazilian construction company, in exchange of assigned public works. President Humala rejected the implication and has avoided speaking to the media on the matter.[3][4]

Humala was arrested by Peruvian authorities in July 2017 and awaits a corruption trial.[5]

Background and military career

Ollanta Humala was born in Lima, Peru on June 27, 1962. His father Isaac Humala, who is of Quechua ethnicity, is a labour lawyer, member of the Communist Party of Peru – Red Fatherland, and ideological leader of the Ethnocacerista movement. Ollanta's mother is Elena Tasso, from an old Italian family established in Peru at the end of the 19th century.[6] He is the brother of Antauro Humala, now serving a 25-year prison sentence for kidnapping 17 Police officers for 3 days and killing 4 of them, and professor Ulises Humala.[7] Humala was born in Peru and attended the French-Peruvian school Franco-Peruano, and later the "Colegio Cooperativo La Union," established by part of the Peruvian-Japanese community in Lima. He began his military career in 1982 when he entered the Chorrillos Military School.

In his military career, Humala was also involved in the two major Peruvian conflicts of the past 20 years, the battle against the insurgent organization Shining Path and the 1995 Cenepa War with Ecuador. In 1992 Humala served in Tingo María fighting the remnants of the Shining Path and in 1995 he served in the Cenepa War on the border with Ecuador.[8]

2000 uprising

See also Locumba uprising (Spanish)

In October 2000, Humala led an uprising in Toquepala[9] against Alberto Fujimori on his last days as President due to multiple corruption scandals. The main reason given for the rebellion was the capture of Vladimiro Montesinos, former intelligence chief who had fled Peru for asylum in Panama after being caught on video trying to bribe an opposition congressman. The return of Montesinos led to fears that he still had much power in Fujimori's government, so Humala and about 40 other Peruvian soldiers revolted against their senior army commander.[10] Montesinos claims that the uprising facilitated his concurrent escape.[11]

Many of Humala's men deserted him, leaving him only 7 soldiers. During the revolt, Humala called on Peruvian "patriots" to join him in the rebellion, and around 300 former soldiers led by his brother Antauro answered his call and were reported to have been in a convoy attempting to join up with Humala. The revolt gained some sympathy from the Peruvian populace with the influential opposition newspaper La República calling him "valiant and decisive, unlike most in Peru". The newspaper also had many letters sent in by readers with accolades to Ollanta and his men.[10]

In the aftermath, the Army sent hundreds of soldiers to capture the rebels. Even so, Humala and his men managed to hide until President Fujimori was impeached from office a few days later and Valentín Paniagua was named interim president. Later Humala was pardoned by Congress and allowed to return to military duty. He was sent as military attaché to Paris, then to Seoul until December 2004, when he was forcibly retired. His forced retirement is suspected to have partly motivated an etnocacerista rebellion of Andahuaylas[2] led by his brother Antauro Humala in January 2005.[12]

In 2002 Humala received a master's degree in Political Science from the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru.[13]

Political career

2006 presidential campaign

In October 2005 Humala created the Partido Nacionalista Peruano (the Peruvian Nationalist Party) and ran for the presidency in 2006 with the support of Union for Peru (UPP).

Ambassador Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, the former Peruvian Secretary-General of the United Nations and founder of UPP, told the press on December 5, 2005, that he did not support the election of Humala as the party's presidential candidate. He said that after being the UPP presidential candidate in 1995, he had not had any further contact with UPP and therefore did not take part in choosing Humala as the party's presidential candidate for the 2006 elections.[14][15]

There were some accusations that he incurred in torture, under the nom de guerre "Capitán Carlos" ("Captain Carlos"), while he was the commander of a military base in the jungle region of Madre Mia from 1992 to 1993. His brother Antauro Humala stated in 2006 that Humala had used such a name during their activities.[16][17] Humala, in an interview with Jorge Ramos, acknowledged that he went under the pseudonym Captain Carlos but stated that other soldiers went under the same name and denied participation in any human rights abuses.[18]

On March 17, 2006, Humala's campaign came under some controversy as his father, Issac Humala, said "If I was President, I would grant amnesty to him (Abimael Guzmán) and the other incarcerated members of the Shining Path". He made similar statements about amnesty for Víctor Polay, the leader of the Túpac Amaru Revolutionary Movement, and other leaders of the MRTA. But Ollanta Humala distanced himself from the more radical members of his family during his campaign.[19][20][21] Humala's mother, meanwhile, made a statement on the March 21 calling for homosexuals to be shot.[22]

Ollanta Humala's brother, Ulises Humala, ran against him in the election, but was considered an extremely minor candidate and came in 14th place in the election.

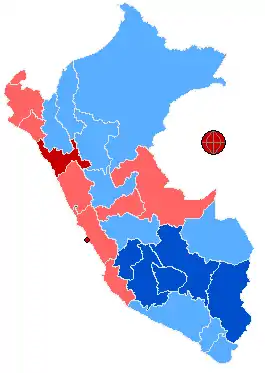

On April 9, 2006, the first round of the Peruvian national election was held. Humala came in first place getting 30.62% of the valid votes,[23] and immediately began preparing to face Alan García, who obtained 24.32%, in a runoff election on June 4.

On May 20, 2006, the day before the first Presidential debate between Alan García and Ollanta Humala, a tape of the former Peruvian intelligence chief Vladimiro Montesinos was released by Montesinos' lawyer to the press with Montesinos claiming that Humala had started the October 29, 2000 military uprising against the Fujimori government to facilitate his escape from Peru amidst corruption scandals. Montesinos is quoted as saying it was a "farce, an operation of deception and manipulation".

Humala immediately responded to the charges by accusing Montesinos of being in collaboration with García's Aprista Party with an intention to undermine his candidacy. Humala is quoted as stating "I want to declare my indignation at the statements" and went on to say "Who benefits from the declarations that stain the honor of Ollanta Humala? Evidently they benefit Alan García".[24][25][26] In another message that Montesinos released to the media through his lawyer he claimed that Humala was a "political pawn" of Cuban President Fidel Castro and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez in an "asymmetric war" against the United States. Montesinos went on to state that Humala "is not a new ideologist or political reformer, but he is an instrument".[27]

On May 24, 2006, Humala warned of possible voter fraud in the upcoming second round elections scheduled for June 4. He urged UPP supporters to register as poll watchers "so votes are not stolen from us during the tabulation at the polling tables." Humala went on to cite similar claims of voting fraud in the first round made by right-wing National Unity candidate Lourdes Flores when she told reporters that she felt she had "lost at the tabulation tables, not at the ballot box". When asked if he had proof for his claims by CPN Radio Humala stated "I do not have proof. If I had the proof, I would immediately denounce those responsible to the electoral system". Alan García responded by stating that Humala was "crying fraud" because the polls show him losing the second round.[28]

On June 4, 2006, the second round of the Peruvian elections were held. With 77% of votes counted and Humala behind García 45.5% to 55.5% respectively, Humala conceded defeat to Alan García and congratulated his opponent's campaign stating at a news conference "we recognise the results...and we salute the forces that competed against us, those of Mr Garcia".[29]

Post-election

On June 12, 2006 Carlos Torres Caro, Humala's Vice Presidential running mate and elected Congressman for the Union for Peru (UPP), stated that a faction of the UPP would split off from the party after disagreements with Humala to create what Torres calls a "constructive opposition". The split came after Humala called on leftist parties to form an alliance with the UPP to become the principal opposition party in Congress. Humala had met with representatives of the Communist Party of Peru – Red Fatherland and the New Left Movement. Humala stated that the opposition would work to "make sure Garcia complies with his electoral promises" and again stated that he would not boycott García's inauguration on July 28, 2006.[30][31]

On August 16, 2006, prosecutors in Peru filed charges against Humala for alleged human rights abuses including forced disappearance, torture, and murder against Shining Path guerillas during his service in San Martín.[32][33] Humala responded by denying the charges and stating that he was "a victim of political persecution". He said the charges were "orchestrated by the Alan Garcia administration to neutralize any alternative to his power".[34]

2011 election

Humala ran again in the Peruvian general election[35] on April 10, 2011, with Marisol Espinoza his candidate for First Vice-President and Omar Chehade as Second Vice President.

On May 19, at National University of San Marcos and with the support of many Peruvian intellectuals and artists (including Mario Vargas Llosa with reservations), Ollanta Humala signed the "Compromiso en Defensa de la Democracia".[36][37] He campaigned as a center-left leader with the desire to help to create a more equitable framework for distributing the wealth from the country's key natural resources, with the goal of maintaining foreign investment and economic growth in the country while working to improve the condition of an impoverished majority.

Going into the June 5 runoff election, he was polling in a statistical tie with opponent Keiko Fujimori.[38] He was elected the 94th president of Peru with 51.5% of the vote.

Presidency

After the news of the election of Ollanta as president the Lima Stock Exchange experienced its largest drop ever,[39][40][41] though it later stabilised following the announcement of Humala's cabinet appointees, who were judged to be moderate and in line with continuity. However he was also said to have inherited "a ticking time bomb of disputes stemming in large part from objections by indigenous groups to the damage to water supplies, crops and hunting grounds wrought by mining, logging and oil and gas extraction" from Alan Garcia.[42] Though he promised the "poor and disenfranchised" Peruvians a bigger stake in the rapidly growing national economy, his "mandate for change...[was seen as] a mandate for moderate change"; his moderation was reflected in his "orthodox" cabinet appointees and his public oath on the Bible to respect investor rights, rule of law and the constitution.[43] He was sworn-in on 28 July 2011.

As part of his "social inclusion" rhetoric during the campaign, his government, led by Prime Minister Salomon Lerner Ghitis, established the Ministry of Development and Social Inclusion in order to coordinate the efficacy of his social programmes.

Ideology

Ollanta Humala expressed sympathy for the regime of Juan Velasco Alvarado, which took power in a bloodless military coup on October 3, 1968, and nationalized various Peruvian industries whilst pursuing a favorable foreign policy with Cuba and the Soviet Union.[44]

During his presidential candidacy in 2006 and his run for the presidency that he ultimately won in 2011, Humala was closely affiliated with other pink tide leaders in Latin America in general and South America in particular. Prior to taking office in 2011, he toured several countries in the Americas where he notably expressed the idea of re-uniting the Peru–Bolivian Confederation. He also visited Brazil, Colombia, the United States, and Venezuela.

Awards and Decorations

Colombia:

Colombia:

_-_ribbon_bar.png.webp) Grand Collar of the Order of Boyaca (11 February 2014)

Grand Collar of the Order of Boyaca (11 February 2014)

Arrest

During the Peruvian presidential election in February 2016, a report by the Brazilian Federal Police implicated Humala in bribery by Odebrecht for public works contracts. President Humala denied the charge and avoided questions from the media on that matter.[45][46] In July 2017, Humala and his wife were arrested and held in pre-trial detention following investigations into his involvement in the Odebrecht scandal.[5][47]

In January 2019, Peruvian prosecutors stated that they had enough evidence to charge Humala and his wife with laundering money from both Odebrecht and the Government of Venezuela.[48]

However, Odebrecht's main projects were carried out under the chairmanships of Alan García and Alberto Fujimori.[49]

See also

References

- The Guardian, April 11, 2011, Peru elections: Fujimori and Humala set for runoff vote

- Diario Hoy, October 31, 2000, PERU, CORONELAZO NO CUAJA

- Leahy, Joe. "Peru president rejects link to Petrobras scandal". FT.com. Financial Times. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- Post, Colin. "Peru: Ollanta Humala implicated in Brazil's Carwash scandal". www.perureports.com. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- McDonnell, Adriana Leon and Patrick J. "Another former Peruvian president is sent to jail, this time as part of growing corruption scandal". latimes.com.

- Justin Vogler (April 11, 2006). "Ollanta Humala: Peru's Next President?". upsidedownworld.

- (in Spanish) (this cannot be correct because the article on Ulises Humala says he is still alive) explored.com.ec, January 5, 2005, Perú: Humala se compara con Chávez y Lucio Gutiérrez Archived August 10, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.]

- "Historia de Ollanta" November 1, 2000 BBC Mundo (in Spanish)

- "Toquepala Prod. Unaffected by Rebellion". BNamericas. October 31, 2000. Archived from the original on April 5, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- "Bid to end Peru rebellion peacefully" November 2, 2000 BBC News

- Libón, Oscar (May 23, 2011). "Montesinos: "Levantamiento de Locumba facilitó mi fuga del país"". Correo. Lima. Archived from the original on June 28, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2014.

- (in Spanish) BBC, January 4, 2005, Perú: insurgentes se rinden

- "Ollanta Se Reencaucha" April 25, 2002 Caretas magazine

- "Ollanta Humala chosen as PNP-UPP presidential candidate" Archived March 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine December 6, 2005 University of British Columbia-Peru Elections 2006

- "Pérez de Cuéllar no avala a UPP" December 6, 2005 Peru 21 (in Spanish) Archived March 3, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- (in Spanish), El Universal, February 6, 2006, "Antauro Humala dice que su hermano Ollanta es el 'capitán Carlos'"

- Chrystelle Barbier "Le candidat nationaliste péruvien, Ollanta Humala, accusé de «tortures»" February 26, 2006 Le Monde (in French)

- Jorge Ramos, "Humala admite que se llamó Cap. Carlos" Archived June 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Peru 21

- (in Spanish), El Universal, March 17, 2006, "Padre de Ollanta Humala pide amnistía para jefes guerrilleros"

- Interview with Ollanta Humala Audio (needs Windows Media Player) (in Spanish) Archived September 7, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Press Conference Speech by Ollanta Humala Video (needs Windows Media Player) El Comercio (in Spanish) Archived December 8, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- "Elena Tasso de Humala, mother of candidate Ollanta Humala, calls for homosexuals to be shot" March 23, 2006.

- "Presidential Election Results". Archived from the original on September 3, 2006.

- "Peru Ex-Spy Chief Says Candidate for President Aided His Escape" May 21, 2006 The New York Times

- Maxwell A. Cameron "Analysis of Audio Tape by Vladimiro Montesinos Concerning Ollanta Humala" Archived June 23, 2006, at the Wayback Machine May 20, 2006 Peru Election 2006: University of British Columbia

- Video of García-Humala Presidential Debate Peruvian National Television Archived May 19, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- El Universal, May 30, 2006, "Montesinos: Humala is a political "pawn" of Chávez and Castro"

- Carla Salazar, "Peruvian Candidate Warns of Voting Fraud" May 24, 2006 CBS News Archived February 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Garcia wins to become Peru president" June 5, 2006 Al-Jazeera

- "Union for Peru Party Splits in Spat With Humala" June 12, 2006 Bloomberg

- "Humala dice que no dará tregua a Alan García" Peru 21 Archived February 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Humala facing rights abuse claims" August 17, 2006 BBC News

- Greg Brosnan, "Peru nationalist Humala faces human rights charges" August 16, 2006 Reuters

- "Humala: I am a Victim of Political Persecution" September 1, 2006 Prensa Latina Archived February 12, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 2, 2011. Retrieved March 29, 2011.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Vargas Llosa reiteró su respaldo a Ollanta Humala a través de video". Elcomercio.pe. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Mario Vargas Llosa under fire for Peru election endorsement, Rory Carroll, The Guardian, April 28, 2011

- "Peru Elections Near: A Look at the Candidates". WOLA, June 1, 2011.

- Carroll, Rory; correspondent, Latin America (June 6, 2011). "Leftwinger Ollanta Humala's narrow win in Peru unnerves markets" – via www.theguardian.com.

- S.A.P, El Mercurio (June 6, 2011). "Bolsa de Perú registra la mayor caída de su historia tras el triunfo de Humala - Emol.com". Emol.

- "Bolsa de Valores registra la mayor caída en su historia - Perú21". June 10, 2011. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- CARLA SALAZAR, Associated Press. "Peru's Garcia leaves conflicts unresolved". Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Mapstone, Naomi (July 7, 2011). "Peru's president to face rebalancing act for rural poor". FT.com. Retrieved July 30, 2011.

- Simon Tisdall "Another angry neighbour for Bush" April 4, 2006 The Guardian

- Leahy, Joe. "Peru president rejects link to Petrobras scandal". FT.com. Financial Times. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- Post, Colin. "Peru: Ollanta Humala implicated in Brazil's Carwash scandal". Peru reports. Retrieved February 23, 2016.

- "Peru's ex-presidents Humala and Fujimori, old foes, share prison". Reuters. July 14, 2017. Retrieved December 18, 2017.

- Martin, Sabrina (January 15, 2019). "Peru: Prosecutors Claim Humala Campaign Financed by Venezuela, Odebrecht". PanAm Post. Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- Vigna, Anne (October 1, 2017). "Brazil's Odebrecht scandal". Le Monde diplomatique.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ollanta Humala. |

- Articles

- "Peru Leans Leftward", April 10, 2006 Council on Foreign Relations

- "Breakdown in the Andes", September/October 2004 Foreign Affairs

- "Ollanta Humala's Path to Peruvian Presidency", August 5, 2011 Sounds and Colours

- "Rebellion in Peru", November 1, 2000 NPR's Talk of the Nation

- "Peru Report", October 30, 2000 NPR's Morning Edition

- "Peru's Election: Background on Economic Issues", April 2006 Center for Economic and Policy Research

- "Peru Elections Near: A Look at the Candidates", June 1, 2011 Washington Office on Latin America

- "He May Be Leader of Peru, but to Outspoken Kin, He’s Just a Disappointment" by William Neuman, The New York Times, August 4, 2012

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| New office | Leader of the Nationalist Party 2005–present |

Incumbent |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Alan García |

President of Peru 2011–2016 |

Succeeded by Pedro Pablo Kuczynski |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Fernando Lugo |

President pro tempore of the Union of South American Nations 2012–2013 |

Succeeded by Dési Bouterse |