Congress of the Republic of Peru

The Congress of the Republic of Peru (Spanish: Congreso de la República) is the unicameral body that assumes legislative power in Peru.

Congress of the Republic Congreso de la República | |

|---|---|

| Extraordinary Period 2020-2021 | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Established | September 20, 1822 (First Constituent Congress) July 26, 1995 (1995 Peruvian general election) |

| Leadership | |

President of Congress | |

1st Vice President of Congress | |

2nd Vice President of Congress | |

3rd Vice President of Congress | |

| Structure | |

| |

Political groups | Popular Action (24) Alliance for Progress (20) |

| Salary | S/187,200 Annually |

| Elections | |

| Proportional representation with a 5%[1] threshold | |

Last election | January 26, 2020 |

Next election | April 11, 2021 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Palacio Legislativo Plaza Bolívar, Lima Republic of Peru | |

| Website | |

| congreso.gob.pe | |

The current Congress of Peru, which was sworn in after the 2020 elections, was elected after the dissolution of the previous Congress by President Martín Vizcarra,[2] triggering the 2019–2020 Peruvian constitutional crisis. Vizcarra issued a decree that set snap elections for 26 January 2020. The representatives will serve out the remainder of the original legislative term, which is set to expire in 2021.

History

.jpg.webp)

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Peru |

| Constitution |

|

|

The first Peruvian Congress was installed in 1822 as the Constitutional Congress led by Francisco Xavier de Luna Pizarro. In 1829, the government installed a bicameral Congress, made up by a Senate and a Chamber of Deputies. This system was interrupted by a number of times by Constitutional Congresses that promulgated new Constitutions that lasted for a couple of years. The Deputies reunited in the Legislative Palace and the Senators went to the former Peruvian Inquisition of Lima until 1930, when Augusto B. Leguía was overthrown by Luis Miguel Sánchez Cerro. He installed a Constitutional Congress (1931–1933) that promulgated the Constitution of 1933. By order of the president, the Peruvian Aprista Party members that were in Congress were arrested for their revolutionary doctrines against the government. When Sánchez Cerro was assassinated in 1933 by an APRA member, General Óscar R. Benavides took power and closed Congress until 1939, when Manuel Prado Ugarteche was elected President. During various dictatorships, the Congress was interrupted by coups d'état. In 1968, Juan Velasco Alvarado overthrew president Fernando Belaúnde by a coup d'état, closing again the Congress.

The 1979 Constitution was promulgated on July 12, 1979 by the Constitutional Assembly elected following 10 years of military rule and replaced the suspended 1933 Constitution. It became effective in 1980 with the re-election of deposed President Fernando Belaúnde. It limited the president to a single five-year term and established a bicameral legislature consisting of a 60-member Senate (upper house) and a 180-member Chamber of Deputies (lower house). Members of both chambers were elected for five-year terms, running concurrently with that of the president. Party-list proportional representation was used for both chambers: on a regional basis for the Senate, and using the D'Hondt method for the lower house. Members of both houses had to be Peruvian citizens, with a minimum age of 25 for deputies and 35 for senators. At the beginning of the 1990s, the bicameral congress had a low public approval rating. President Alberto Fujimori did not have the majority in both chambers, the opposition lead the Congress, imposing the power that Fujimori had as President. He made the decision of dissolving Congress by a self-coup to his government in 1992.

Following the self-coup, in which Congress was dissolved, the Democratic Constitutional Congress established a single chamber of 120 members. The Democratic Constitutional Congress promulgated the 1993 Constitution in which gave more power to the President. The new unicameral Congress started working in 1995, dominated by Fujimori's Congressmen that had the majority. The Congress permits a one-year term for a Congressman to become President of Congress.

Membership

Qualifications

Article 90 of the Peruvian Constitution sets three qualifications for congressmen: (1) they must be natural-born citizens; (2) they must be at least 25 years old; (3) they must be an eligible voter.[3] Candidates for president cannot simultaneously run for congress while vice-presidential candidates can. Furthermore, Article 91 states that high ranking government officers and any member of the armed forces or national police can only become congressmen six months after leaving their post.[3]

Elections and term

Congressmen serve for a five-year term and can be re-elected indefinitely even though this is very rare. Elections for congress happen simultaneously as the election for president. Seats in congress are assigned to each region in proportion to the region's population. Congressional elections take place in April.

The D'Hondt method, a party-list proportional representation system, is used to allocate seats in congress. Political parties publish their party list for each region ahead of the election. Candidates do not need to be members of the political party they run for but may run for such party as a guest. Each candidate is assigned a number within the list. The citizenry thus votes for the party of their preference directly. Additionally, voters may write two specific candidates' number on the ballot as their personal preference. The newly elected congress takes office on the 26th of July of the year of the election.

Disciplinary action

Congressmen may not be tried or arrested without prior authorization from Congress from the time of their election until a month after the end of their term.[3] Congressmen must follow the Congress' code of ethics which is part of its self-established Standing Rules of Congress.[4] La Comisión de Ética Parlamentaria, or Parliamentary Ethics Committee, is incharge of enforcing the code and punishing violators. Discipline consist of (a) private, written admonishments; (b) public admonishments through a Congressional resolution; (c) suspension from three to 120 days from their legislative functions.[4]

Any congressmen may lose their parliamentary immunity if authorized by Congress.[3] The process is started by the Criminal Sector of the Supreme Court who presents the case to the Presidency of Congress. The case is then referred to a special committee of 15 congressmen known as Comisión de Levantamiento de Inmunidad Parlamentaria, or Committee on Lifting Parliamentary Immunity, that decides if the petition should be heard by the body as a whole. The accused congressmen has the right to a lawyer and to defend himself before the committee and before the Plenary Assembly.[4] The final decision is then communicated back to the Supreme Court.

Salary

Each congressmen makes about US$6,956 per month. This includes different assignment-specific allowances as well as tax charges.[5]

Officers

President and Bureau

The most important officer is the President of Congress who is fourth in line of presidential succession if both the President and both vice-presidents are incapable of assuming the role. The President of Congress can only serve as interim president as he is required to call new elections if all three executive officers are not incapable of serving.[3] This has happened once since the adoption of the current constitution when Valentín Paniagua became the interim president after the fall of the Alberto Fujimori regime in 2000.

The President of Congress is elected for a one-year term by the rest of Congress. Re-election is possible but uncommon. The President of Congress is almost always from the majority party. Its most important responsibility is to control and guide debate in Congress. He also signs, communicates and publishes bills and other decisions made by Congress. He may delegate any of these responsibilities to one of the vice-presidents of Congress.[6] The president serves along three vice-presidents who are collectively known as Mesa Directiva del Congreso, known as the Bureau in English.[7] The three vice-presidents are not always from the same party as the president. The Bureau approves all administrative functions as well as all of Congress' internal financial policy and hiring needs. Any member of the Bureau may be censored by any member of Congress.

Executive Council

El Consejo Directivo, or Executive Council, consists of the four members of the Bureau as well as representatives from each political party in Congress which are known as Executive-Spokespersons. Its composition is directly proportional to the number of seats each party holds in Congress. The Council has administrative and legislative responsibilities. Similar to the United States House Committee on Rules, it sets the calendar for the Plenary Assembly and fixes floor time for debating calendar items.[8]

Board of Spokespersons

Each political party in Congress chooses a Spokesperson who acts as the party leader and is a member of the Board of Spokespersons alongside the members of the Bureau. The Board of Spokespersons main role deals with committee assignments as well as the flow of bills from the committees to the Plenary Assembly.[9]

Secretariat General

La Oficialía Mayor, or Secretariat General, is the body of personnel led by the Secretary-General. It is responsible for assisting all members of Congress with daily managerial tasks. The Secretary-General is chosen and serves under the direction of the Bureau and Executive Council.[10]

Committees

Standing Committees are in charge of the study and report of routine business of the calendar, especially in the legislative and oversight function. The President of Congress, in coordination with Parliamentary Groups or upon consultation with the Executive Council, proposes the number of Standing Committees. Each party is allocated seats on committees in proportion to its overall strength.

Most committee work is performed by 24 standing committees.[4] They examine matters within their jurisdiction of the corresponding government departments and ministries.[3] They may also impede bills from reaching the Plenary Assembly.[4]

There are two independent committees, the Permanent Assembly and the Parliamentary Ethics Committee.[4]

Investigative and Special Committees

Investigative committee are in charge of investigating a specific topic as directed by Article 97 of the Constitution. Appearances before investigative committees are compulsory, under the same requirements as judicial proceedings. Investigative committee have the power to access any information necessary, including non-intrusive private information such as tax filings and bank financial statements. Investigative committees final reports are non-binding to judicial bodies.[3] Special committees are set up for ceremonial purposes or for the realization of special study or joint work with other government organizations or amongst congressional committees. They disband after they fulfill their assigned tasks.[4]

The Permanent Assembly

The Permanent Assembly, or Comisión Permanente, fulfills the basic functions of Congress when it is under recess or break. It is not dissolved even if Congress is dissolved by the President. It also fulfills some Constitutional functions while Congress is in session similar to what an upper-chamber would. It has the responsibility of appointing high-ranking government officers and commencing the removal process of them as well as the heads of the two other branches of government. The Plenary Assembly may assign this committee special responsibilities excluding constitutional reform measures, approval of international treaties, organic acts, the budget, and the General Account of the Republic Act.[3] The Assembly consist of twenty-five percent of the total number of congressmen elected proportionally to the number of seats each party holds in Congress. They are installed within the first 15 days of the first session of Congress' term.[3]

Parliamentary Ethics Committee

Congressmen must follow the Congress' code of ethics which is part of its self-established Standing Rules of Congress. La Comisión de Ética Parlamentaria, or Parliamentary Ethics Committee, is in charge of enforcing the code and punishing violators. Discipline consists of (a) private, written admonishments; (b) public admonishments through a Congressional resolution; (c) suspension from 3 to 120 days from their legislative functions.[4]

Functions

Article 102 of the Peruvian Constitution delineated ten specific functions of Congress which deal with both its legislative power as well as its role as a check and a balance to the other branches of government:[3]

- To pass laws and legislative resolutions, as well as to interpret, amend, or repeal existing laws.

- To ensure respect for the Constitution and the laws; and to do whatever is necessary to hold violators responsible.

- To conclude treaties, in accordance with the Constitution.

- To pass the Budget and the General Account.

- To authorize loans, in accordance with the Constitution.

- To exercise the right to amnesty.

- To approve the territorial demarcation proposed by the Executive Branch.

- To consent to the entry of foreign troops into the territory, whenever it does not affect, in any manner, national sovereignty.

- To authorize the President of the Republic to leave the country.

- To perform any other duties as provided in the Constitution and those inherent in the legislative function.

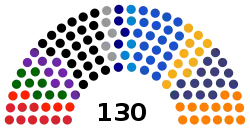

Current composition and election results

The election was the most divided in Peruvian history, with no party receiving more than 11% of the vote. The Fujimorist Popular Force, the largest party in the previous legislature, lost most of its seats, and the American Popular Revolutionary Alliance (APRA) had its worst ever election result, failing to win a seat for the first time since before the 1963 elections. New or previously minor parties such as Podemos Perú, the Purple Party and the Agricultural People's Front had good results. Contigo, the successor to former president Pedro Pablo Kuczynski's Peruvians for Change party, failed to win a seat and received only around 1% of the vote. The result was seen as representative of public support for president Martín Vizcarra's anti-corruption reform proposals.

| |||||

| Party | Seats | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Popular Action | 25 | ||||

| Alliance for Progress | 22 | ||||

| Agricultural People's Front of Peru | 15 | ||||

| Popular Force | 15 | ||||

| Union for Peru | 13 | ||||

| Podemos Peru | 11 | ||||

| We Are Peru | 11 | ||||

| Purple Party | 9 | ||||

| Broad Front | 9 | ||||

| Source: ONPE | |||||

Possible Reform

President Martín Vizcarra proposed a series of political reforms as a response to the CNM audios scandal during his Independence Day annual message. The first proposal would prohibit the direct reelection of congressmen. The second would split the legislative branch into a bicameral body as was before the 1993 Constitution.

The new bicameral legislature would consist of a Senate with 50 Senators and a chamber of Deputies with 130 Deputies. Before the 1993 Constitution there were 60 Senators and 180 Deputies. Legislators would be elected by direct elections similar to the ones held now for Congress for a period of five years. The presidency of Congress would alternate annually between the presidency of each one of the Chambers.

Each chamber would take on special duties and responsibilities unique to their chamber. The Senate would approve treaties, authorize the mobilization of foreign troops into the national territory, and have the final say on accusations of high-ranking officials made by the Chamber of Deputies. The Chamber of Deputies would approve the budget, delegate legislative faculties to the executive, and conduct investigations.

The Constitution states that constitutional amendments are to be ratified by a referendum or by a two-thirds votes in two successive legislative sessions of congress. Since the promulgation of the 1993 Constitution all amendments have been ratified by the later method and never by referendum.[3] President Vizcarra has insisted in making the bicameralism question a matter of referendum which has become an extremely popular idea in the country.[11] The constitutional referendum is set for December 9, 2018.[12]

References

- https://perureports.com/2016/03/31/perus-small-political-parties-scramble-survive/

- "Peru's president dissolves Congress to push through anti-corruption reforms". The Guardian. 1 October 2019. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- "Peru's Constitution of 1993 with Amendments through 2009" (PDF). constituteproject.org. Constitute. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Reglamento del congreso de la república" (PDF). congreso.gob.pe (in Spanish). Congreso de la República del Perú. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- Redacción, EC (29 June 2017). "¿Cuánto ganan los congresistas de Latinoamérica?". El Comercio (in Spanish). El Comercio. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "President of Congress". congreso.gob.pe. Congreso de la República del Perú. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Bureau". congreso.gob.pe. Congreso de la República del Perú. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Executive Council". congreso.gob.pe. Congreso de la República del Perú. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Board of Spokespersons". congreso.gob.pe. Congreso de la República del Perú. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Secretariat General". congreso.gob.pe. Congreso de la República del Perú. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Peruvian President Martin Vizcarra proposes referendum on political and judicial reform". The Japan Times Online. 29 July 2018. Retrieved 2 October 2018.

- PERÚ, Empresa Peruana de Servicios Editoriales S. A. EDITORA. "Peru PM: Referendum must be held on December 9". andina.pe (in Spanish).

.svg.png.webp)