One Australia

One Australia was the immigration and ethnic affairs policy of the Liberal-National Opposition in Australia, released in 1988. The One Australia policy proclaimed a vision of "one nation and one future". It called for an end to multiculturalism and opposed a treaty with Aboriginal Australians.

| ||

|---|---|---|

Term of Government (1996-2007)

Ministries Elections |

||

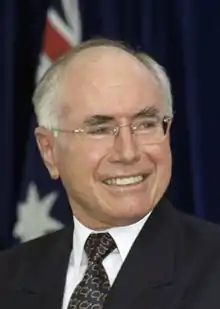

The policy set the scene for the August 1988 suggestion by Leader of the Opposition John Howard that the rate of Asian immigration to Australia be reduced.

History

Howard first flagged the concept of the One Australia policy on a trip to Perth in July 1988, having recently returned from a visit with Margaret Thatcher in Britain. One Australia was to be the name of the Liberal-National Coalition's immigration and ethnic affairs policy.[1]

During an interview on the John Laws radio programme on 1 August 1988, Howard detailed the policy, expressing his preference to bias immigration towards skilled applicants rather than family reunion.[2] Later that afternoon, on the ABC PM programme, Howard discussed the policy in relation to Asian immigration to Australia:

I do believe that if it is – in the eyes of some in the community – that it's too great, it would be in our immediate-term interest and supporting of social cohesion if it were slowed down a little, so the capacity of the community to absorb it was greater.[3][4]

Howard's Shadow Finance Minister, John Stone, elaborated, saying that "Asian immigration has to be slowed. It's no use dancing around the bushes".[5] Ian Sinclair, National Party leader in the Coalition, also supported the policy, saying:

"What we are saying is that if there is any risk of an undue build-up of Asians as against others in the community, then you need to control it ... I certainly believe, that at the moment we need ... to reduce the number of Asians ... We don't want the divisions of South Africa, we don't want the divisions of London. We really don't want the colour divisions of the United States."

There were widespread objections to the policy from within the Liberal Party, including from Victorian Premier Jeff Kennett, New South Wales Premier Nick Greiner, former Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser, and former immigration ministers Ian Macphee and Michael MacKellar.[5]

The Labor government sought to quickly exploit Howard's Asian remarks by introducing a parliamentary motion rejecting the use of race to select immigrants. Howard opposed this motion.[7][8][9] In an unusual show of dissent, three Liberal MPs—Ian Macphee, Steele Hall and Philip Ruddock—defied their leader by crossing the floor and voting with the Labor government.[10] Macphee lost preselection the following year.[11]

Criticising his own party's policy, Steele Hall said in a speech to Parliament:

The question has quickly descended from a discussion about the future migrant intake to one about the level of internal racial tolerance. The simple fact is that public opinion is easily led on racial issues. It is now time to unite the community on the race issue before it flares into an ugly reproach for us all.[10]

In a speech to the "Terra Australis to Australia" conference in Canberra, August 1988, Prime Minister Bob Hawke responded to the Opposition's One Australia policy:

In the field of immigration and ethnic affairs, the "One Australia" ideology seems to connote a return to the dark days of narrow minded intolerance, fear of difference and pressure to assimilate. It is less about uniting Australians than dividing them.[12]

One Australia was officially launched by John Howard on 22 August 1988. The policy document, whose title was personally chosen by Howard, stated the Coalition's ideal to create "One Australia and welcome all those who share our vision and are ready to contribute to it", detailing a vision of "one nation and one future" which included the rejection of Aboriginal land rights. In September 1988, John Howard criticised multiculturalism, saying "To me, multiculturalism suggests that we can't make up our minds who we are or what we believe in", and the idea of an Aboriginal treaty, saying "I abhor the notion of an Aboriginal treaty because it is repugnant to the ideals of One Australia".[3]

One Australia became the centrepiece of Howard's general policy manifesto, "Future Directions – It's Time for Plain Thinking", which was released in December 1988.

In a January 1989 interview with Gerard Henderson, Howard elaborated on his reasons for opposing multiculturalism:

The objection I have to multiculturalism is that multiculturalism is in effect saying that it is impossible to have an Australian ethos, that it is impossible to have a common Australian culture. So we have to pretend that we are a federation of cultures and that we've got a bit from every part of the world. I think that is hopeless.[3][13]

In the months following the release of the One Australia policy, there was a decline in investment in Australia by Asian businesses.[14] Some political commentators later postulated that the dissent within the Liberal Party over immigration policy weakened Howard's leadership position, contributing to him being overthrown as Liberal Party leader by Andrew Peacock.[15]

Commentary on the One Australia policy

- In 1993, Liberal Party MP, Peter Costello, dismissed the One Australia policy as just "a passing policy".[16][17]

- In a 2007 article in the British newspaper The Guardian, left wing journalist John Pilger claimed that the One Australia Policy was a forerunner to the One Nation political party.[18]

References

- Maddox, Marion (2005). God Under Howard: The Rise of the Religious Right in Australian Politics. Allen & Unwin. pp. 112–114. ISBN 978-1-74114-568-7.

- Jupp, James; John Warhurst and Marian Simms (2002). "Ethnicity and immigration" (PDF). 2001: The Centenary Election. University of Queensland Press (UQP). Archived from the original on 2002. Retrieved 21 August 2007.

- Markus, Andrew (2001). Race: John Howard and the Remaking of Australia. Allen & Unwin. pp. 85–89. ISBN 978-1-86448-866-1.

- "Asian influence spices up contest". The Australian. 27 February 2007. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- Peter, Mares (2002). Borderline: Australia's Response to Refugees and Asylum Seekers in the Wake of the Tampa. UNSW Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-0-86840-789-0.

- Markus, Andrew (2001). Race: John Howard and the Remaking of Australia. Allen & Unwin. p. 89. ISBN 978-1-86448-866-1.

- "IMMIGRATION POLICY: Suspension of Standing and Sessional Orders". Parliament of Australia (Hansard). 25 August 1988. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- Parkinson, Tony (21 June 2005). "Howard turns dissent into democracy". The Age. Retrieved 3 August 2007.

- Bob, Hawke (8 May 2001). "Speeches by The Hon RJL Hawke AC". UniSA. Archived from the original on 17 September 2007. Retrieved 19 August 2007.

- Ramsey, Alan (12 April 2006). "The lost art of crossing the floor". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 22 August 2007.

- Hall, Bianca (23 February 2014). "Liberal Wets hang out principles on asylum-seeker policy to dry". WAtoday. Perth: Fairfax Media. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Hawke, Bob (21 August 1988). "Speech by the Prime Minister" (PDF). "Terra Australis to Australia" conference. UniSA. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 12 December 2007.

- "Relaxed and comfortable". The Age. 10 September 2005. Retrieved 30 November 2007.

- Morris, Meaghan (1998) [1998]. Too Soon Too Late: History in Popular Culture. Indiana University Press. pp. 306–307. ISBN 978-0-253-33395-7. Retrieved 18 December 2007.

- Kelly, Paul (1994) [1994]. The End of Certainty: Power, Politics, and Business in Australia. Allen & Unwin. p. 457. ISBN 978-1-86373-757-9. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- Costello, Peter (September 1993). "The Liberal Party and its Future". Australian Quarterly. 65 (3): 17. doi:10.2307/20635729. JSTOR 20635729.

- Brawley, Sean (27 April 2007). "A Comfortable and Relaxed Past': John Howard and the 'Battle of History'". The Electronic Journal of Australian and New Zealand History. James Cook University. Retrieved 9 December 2007.

- Pilger, John (19 January 2007). "Cruelty and xenophobia stir and shame the lucky country". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 10 December 2007.