Ordination of women in Protestant denominations

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart as clergy to perform various religious rites and ceremonies such as celebrating the sacraments. The process and ceremonies of ordination varies by denomination. One who is in preparation for, or who is undergoing the process of ordination is sometimes called an ordinand. The liturgy used at an ordination is sometimes referred to as an ordinal.

| Part of a series on |

| Christianity and gender |

|---|

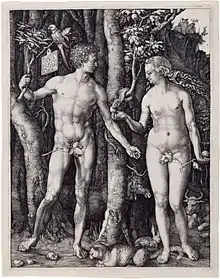

"Adam and Eve" by Albrecht Dürer (1504) |

Ordination of women has been taking place in an increasing number of Protestant churches during the 20th century.

While ordination of women has been approved in many denominations over the past half century, it is still a very controversial and divisive topic.

Overview of the theological debate

Most (although not all) Protestant denominations ordain church leaders who have the task of equipping all believers in their Christian service (Ephesians 4:11–13). These leaders (variously styled elders, pastors, or ministers) are seen to have a distinct role in teaching, pastoral leadership.

Protestant churches have historically viewed the Bible as the ultimate authority in church debates (the doctrine of sola scriptura), as such the debate over women's eligibility for such offices normally centers around interpretation of certain Biblical passages relating to teaching and leadership roles. The main passages in this debate include 1 Cor. 11:2–16, 1 Cor. 14:34–35 and 1 Tim. 2:11–14, 1 Tim. 3:1–7, Tit. 1:5–9

Increasingly however, supporters of women in ministry argue that the Biblical passages used to argue against women's ordination might be read differently when more understanding of the unique historical context of each passage is available.[1] They further argue that the New Testament shows that women did exercise certain ministries in the apostolic Church (e.g., Acts 21:9, Acts 18:18, Romans 16:1–4, Romans 16:7; 1 Cor. 16:19, Philippians 4:2–3, and John 20:1–18. Often quoting Galatians 3:28,they argue that the good news brought by Jesus has broken down all barriers and that female ordination is an equality issue that Jesus would have approved of. They also quote John 20:17–18, and argue that in talking to Mary, Jesus is calling for women to evangelize

In turn, those who argue for a male only ministry will say that the claims to contexts that change the apparent meaning of the texts at hand to one supporting female ordination are in fact spurious, that the passages that appear to show women in positions of authority do not in fact do so and the idea that the good news of Jesus brings equality before God only relates to salvation and not to roles for ministry.

By tradition

Mennonite

- The Canadian Conference of Mennonite Brethren Churches' has ordained women.[3]

- The Mennonite Church Canada ordains women.

- The Mennonite Brethren Church does not ordain women to be lead pastors.

- The Mennonite Church USA ordains women.

- The Brethren in Christ Church ordains women at all levels of leadership, including Bishop.[4]

Anglican

The ordination of women in the Anglican Communion has been increasingly common in certain provinces since the 1970s. However, several provinces (such as the Church of Pakistan—a united Protestant Church created as a result of a union between Anglicans, Lutherans, Methodists and Presbyterians) and certain dioceses within otherwise ordaining provinces (such as the Diocese of Sydney in the Anglican Church of Australia), continue to ordain only men.[5][6] Disputes over the ordination of women have contributed to the establishment and growth of conservative separatist tendencies, such the Anglican realignment and Continuing Anglican movements.

Some provinces within the Anglican Communion, such as the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America, ordain women to the three traditional holy orders of bishop, priest and deacon. Other provinces ordain women as deacons and priests but not as bishops; others still as deacons only; and seven provinces do not approve the ordination of women to any order of ministry.[7]

Baptist

The very diverse organizations which employ the term Baptist in self-designation:

- The Baptist organizations in Germany and Switzerland (Bund Evangelisch-Freikirchlicher Gemeinden, Bund Schweizer Baptistengemeinden) ordain women.[8]

- The Southern Baptist Convention (the largest of the various Baptist denominations) does not support the ordination of women; however, some churches that are members of the SBC have ordained women. Though each SBC church is autonomous and may choose whether or not to ordain women, the local associations and state conventions have the right to not seat messengers from those churches at the annual meetings, and some have done so.

- Baptist groups in the United States that ordain women include American Baptist Churches USA, North American Baptist Conference, Alliance of Baptists, Cooperative Baptist Fellowship (CBF), Missionary Baptist Conference, USA, National Baptist Convention, USA, Inc. and Progressive National Baptist Convention.[9]

- The General Association of Baptists (mostly United States) (some would call these General Baptists, or Arminian Baptists) ordain women.

- The Okinawa Baptist Convention,[10] Japan ordains women to be Pastors of the church.

- The General Association of Regular Baptist Churches does not ordain women.[11]

- The Baptist Union of Great Britain ordains women. [12]

Europe

- The Lutheran churches within the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) ordain women and have women as bishops.

- The Independent Evangelical-Lutheran Church in Germany does not ordain women.

- The Evangelical Lutheran Church of Latvia reversed its earlier (1975) decision to ordain women as pastors. Since 1993 it no longer does so in practice. Since 2016 this principle has been affirmed in its constitution.

- The Lutheran state churches in the Nordic countries ordain women as pastors and have women as bishops. The first female pastors were ordained in the Church of Denmark in 1948, in Sweden in 1960, Norway in 1961, in Iceland in 1974 and in Finland in 1988.

- While the Church of Sweden ordained its first female pastors in 1960, there was a considerable debate in this church of the ordination of women, which led to marginalization of a vocal high-church minority, which successively subdivided into loyalist high-church adherents on one hand and the splinter group Missionsprovinsen which was formed in 2003 but in 2005 was separated as a church body from the Church of Sweden.

- Although the ordination of women was accepted by the Church of Finland in 1988, controversy over the issue occasionally surfaces among the more conservative wing of the church. Occasional debate on the matter has caused church membership resignations.[13]

- The Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church (EELC) began to ordain women in 1967 and 2004 all obstacles that forbade women to be consecrated as bishops were removed although none have yet consecrated.[14]

- The Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Slovakia ordains women as pastors since 1951 and women can be elected bishops.

- The Slovak Evangelical Church of the Augsburg Confession in Serbia ordains women as pastors. Out of 20 pastors in Serbia, 6 are women.

United States

- The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) is the largest Lutheran body in the USA. The church bodies that formed the ELCA in 1988 began ordaining women in 1970 when the Lutheran Church in America ordained the Rev Elizabeth Platz. In 2017 about 27% of the rostered leaders were women and about 50% of the seminarians preparing for ministry were women.[15] In 2013 the first female presiding bishop of the ELCA, Elizabeth Eaton, was elected.[16] In 2018 16 of the 65 synodical bishops (17 bishops including Presiding Bishop Eaton) in the ELCA were women [17]

- The General Lutheran Church ordains women.

- The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod (LCMS), which is the second largest Lutheran body in the United States, does not ordain women.

- The Lutheran Congregations in Mission for Christ (LCMC) also allows for the ordination of women.[18]

- The North American Lutheran Church, was founded in 2010 does ordain women.[19] The NALC has established ecumenical dialog with a number of Lutheran bodies, both those that ordain women and those that do not.

- The Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran Synod does not ordain women.

- The Evangelical Lutheran Synod does not ordain women.

- The Church of the Lutheran Confession does not ordain women.[20]

- The Lutheran Evangelical Protestant Church (GCEPC) has ordained women since its inception in the year 2000. Ordination of women is not a controversial issue in the LEPC/GCEPC. Women are ordained/consecrated at all levels, including deacon, priest, and bishop in the LEPC/GCEPC.

Africa

- The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Tanzania (ELCT) decided to ordain women in 1990, but does not have any women bishops. Some dioceses are still opposed to the ordination of women.[21]

- The Ethiopian Evangelical Church Mekane Yesus (EECMY) began to ordain women in 2000[22] but doesn't continue this practice since confessional lutheranism has become stronger in this church body during recent years.

Methodist

- The United Methodist Church ordains women. In 1880, Anna Howard Shaw was ordained by the Methodist Protestant Church; Ella Niswonger was ordained in 1889 by the United Brethren Church. Both denominations later merged into the United Methodist Church. In 1956, the Methodist Church in America granted ordination and full clergy rights to women. Since that time, women have been ordained full elders (pastors) in the denomination, and 21 have been elevated to the episcopacy. In 1967 Noemi Diaz is the first Hispanic woman ordained by an Annual Conference. The New York Annual Conference did the honors.[23][24][25] The first woman elected and consecrated Bishop within the United Methodist Church (and, indeed, the first woman elected bishop of any mainline Christian church) was Marjorie Matthews in 1980.[26] Leontine T. Kelly, in 1984, was the first African-American woman elevated to the episcopacy in any mainline denomination. In Germany Rosemarie Wenner is since 2005 leading bishop in the United Methodist Church. Bishop Karen Oliveto ,currently serving, is the first openly lesbian bishop in The United Methodist Church.[27]

- The Primitive Methodist Church does not ordain women as elders nor does it license them as pastors or local preachers;[28] the PMC does consecrate women as deaconesses.[28]

- The Evangelical Wesleyan Church (EWC) does not ordain women as elders although it does commission women as deaconesses.[29]

- The Fundamental Methodist Conference does not ordain women.

- The Southern Methodist Church does not ordain women.

- The Free Methodist Church has ordained women since 1911.[30]

- The Bible Methodist Connection of Churches ordains women.[31]

- The Salvation Army ordains women and has done since its inception. Catherine Booth was co-founder, with her husband William.

- The Church of the Nazarene ordains women, with the first women being ordained since 1908.

- The Wesleyan Methodist Church (which is now the Allegheny Wesleyan Methodist Connection and Wesleyan Church) has ordained women as ministers since near its inception, and claims to be one of the first to ordain women in the modern era.[32]

Pentecostal

- The Pentecostal church in Germany allows ordination of women.[33]

- The Pentecostal church in Sweden allows ordination of women.

- The Pentecostal Mission does not ordain women pastors.

- The occurrence of women pastors, often as co-pastors along with their husbands, is frequent in the Pentecostal movement especially in churches not affiliated with a denomination; they may or may not be ordained. Notable women pastors include Paula White and Victoria Osteen.

- The Assemblies of God USA do ordain women and have women in leadership throughout the Church.

- Church of God in Christ (COGIC) does not ordain women as elder or bishop

Scotland

- Women were commissioned as deacons from 1935, and allowed to preach from 1949.

- In 1963 Mary Levison petitioned the General Assembly for ordination.

- Woman elders were introduced in 1966 and women ministers in 1968.

- The first female Moderator of the General Assembly was Dr Alison Elliot in 2004.

- The United Free Church of Scotland ordains women.

- The Free Church of Scotland does not ordain women.

- The Free Church of Scotland (Continuing) does not ordain women.

- The Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland based in Scotland, Australia and Zimbabwe does not ordain women.

- The Associated Presbyterian Churches based in Scotland does not ordain women.

England/Wales

- The United Reformed Church in the United Kingdom ordains women.

- The International Presbyterian Church based in the UK Europe and Korea, does not ordain women.

- The Evangelical Presbyterian Church in England and Wales does not ordain women.

- The Free Church of England does not ordain women.

- The Presbyterian Church of Wales ordains women.

Ireland

- The Presbyterian Church in Ireland does ordain women.

- The Non-subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland ordains women.

- The Free Presbyterian Church of Ulster does not ordain women.

- The Evangelical Presbyterian Church (Ireland) does not ordain women.

- The Reformed Presbyterian Church of Ireland does not ordain women.

Netherlands

- The Dutch Reformed Church does ordain women except the reformed union[34]

- The Reformed Churches in the Netherlands (Liberated) does not ordain women.

- The Reformed Congregations in the Netherlands does not ordain women.

Belgium

- The United Protestant Church in Belgium does ordain women.

Luxembourg

- The Protestant Reformed Church of Luxembourg does ordain women.

- The Protestant Church of Luxembourg does ordain women.

France

- The Reformed Church of France ordains women.[35]

The United Protestant Church of France ordains women.

Switzerland

- The Swiss Reformed Church does ordain women.

Germany

- The united and reformed churches within the Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD) ordain women and have women as bishops.

Eastern Europe

- The Reformed Church in Hungary ordains women.

- The Polish Reformed Church ordains women.

North America

- The Presbyterian Church (USA). The PC(USA) was formed in 1983 by a merger of the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS - southern church) and the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America (UPCUSA - northern church). The PC(USA) has always ordained women. With regards to its predecessor bodies - in 1893, Edith Livingston Peake was appointed Presbyterian Evangelist by First United Presbyterian of San Francisco.[36] Between 1907 and 1920 five more women became ministers.[37] The Presbyterian Church (USA) began ordaining women as elders in 1930, and as ministers of Word and sacrament in 1956. By 2001, the numbers of men and women holding office were almost equal.[38] The first woman to be ordained in the Presbyterian Church in the United States (PCUS/Southern Church) was Rev. Rachel Henderlite who was ordained by a predominantly African American congregation in Richmond, VA in 1965.[39]

- The Presbyterian Church in America does not ordain women.[40] In 1997, the PCA even broke its fraternal relationship with the Christian Reformed Church over this issue.[41]

- The Free Reformed Churches of North America ordain men only.

- The Cumberland Presbyterian Church. In 1888 Louisa Woosley was licensed to preach. She was ordained in 1889. She wrote Shall Woman Preach.

- The Christian Reformed Church in North America began ordaining women in 1995.[42] As a result, several conservative congregations formed the United Reformed Churches in North America, and the CRC's position as a member of the North American Presbyterian and Reformed Council (NAPARC) was suspended in 1997.[43] Several individual congregations continue to oppose women's ordination and women are not seated at some Classes (regional assemblies).

- The Orthodox Presbyterian Church does not ordain women.[44]

- The Reformed Church in America began allowing for the ordination of women in 1979.[45]

- The United Church of Christ. Antoinette Brown was ordained as a minister by a Congregationalist Church in 1853, though this was not recognized by her denomination.[46] She later became a Unitarian. The Christian Connection Church, which later merged with the Congregationalist Churches to form the Congregational Christian Church, ordained women as early as 1810. Women's ordination is now non-controversial in the United Church of Christ.

- The Evangelical Covenant Order of Presbyterians (ECO) ordains women as both Teaching Elders (pastors) and Ruling Elders.

- The Evangelical Presbyterian Church (EPC) allows individual congregations to determine whether or not they ordain women.

- The United Church of Canada ordains women. The church was divided during the 1930s by this issue inherited from the churches it brought together, the United Church ordained its first woman minister, Reverend Lydia Emelie Gruchy, of Saskatchewan Conference in 1936. In 1953, Reverend Lydia Emelie Gruchy was the first Canadian woman to receive an honorary Doctor of Divinity.[47]

Australia

- The Uniting Church in Australia has ordained women since it formed in 1977. The three member denominations, the Congregational Union of Australia, the Methodist Church of Australasia and the Presbyterian Church of Australia had all ordained women prior to Union. The Congregational Union of Australia ordained the first woman in Christian ministry in Australia, Rev Winifred Kiek in 1927. The Methodist Church of Australasia first ordained women (Rev Margaret Sanders and Rev Coralie Ling) in 1969, while the Presbyterian Church of Australia ordained its first woman minister in 1974. After formation of the Uniting Church in Australia, the continuing Presbyterian Church of Australia reversed the decision to ordain women in 1991.

- The Presbyterian Church of Australia does not ordain women. As mentioned above some of its congregations left to join the new Uniting Church in 1977, 14 years later in 1991 it ceased ordaining women to the ministry, but the rights of women ordained prior to this time were not affected.[48]

Pakistan

- The Presbyterian Church of Pakistan ordains women.

Other Protestant

- The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) do not ordain anyone but have had women in leadership roles such as Recorded Minister since they first started in 1652. See Elizabeth Hooton and Mary Fisher[49][50] though it was longer before they held positions as clerk of a yearly meeting (e.g., Mary Jane Godlee as first female clerk of the London Yearly Meeting in 1921) though they were clerks of the then separate women's meetings which did wield authority.[51]

- 'Christian Connection Church: An early relative of the Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) and the United Church of Christ, this body ordained women as early as 1810. Among them were Nancy Gove Cram, who worked as a missionary with the Oneida Indians by 1812, and Abigail Roberts (a lay preacher and missionary), who helped establish many churches in New Jersey. Others included Ann Rexford, Sarah Hedges and Sally Thompson.

- The Christian and Missionary Alliance in the USA does not ordain women, but it does in other nations. A female minister in Philippines, Ruth Tablada, has recently been ordained. The Christian and Missionary Alliance Church in Canada also ordains women.[52][53][54]

- The Moravian Church ordains women.[55]

- The Czechoslovak Hussite Church ordains women.

- The Seventh-day Adventist Church officially does not ordain women in most of the world, but in regions of the United States, the Netherlands, parts of Germany, and China may occasionally ordain women. These ordinations are considered irregular and are not officially recognized in the church yearbook. In some parts of the world the Adventist Church, commissions women instead of ordaining. They can perform almost the same duties as an ordained minister but do not hold the title of ordained. This is because recent votes at the worldwide General Conference Sessions turned down a proposal to allow ordination of women. There was a strong polarization between nations, with Western countries and North Asia Pacific generally voting in support and other countries generally voting against. A further proposal to allow local choice was also turned down. In practice, there are numerous women working as ministers and in leadership positions. The most influential co-founder of the church, Ellen G. White, was a woman, but never ordained.

- Churches of Christ, because of their conservative stance, generally do not ordain women.

- The Christian Leaders Alliance allows women to serve as deacon ministers.[56]

Women as Protestant bishops

Some Protestant Churches, including those of the Lutheran, Hussite, Anglican, Methodist and Moravian traditions, have allowed women to become bishops:[46]

- 1924: Mount Sinai Holy Church of America- Ida B. Robinson served as founder and first presiding bishop

- 1929: Old Catholic Mariavite Church in Poland (and Catholic Mariavite Church, a 1935 schism from the Old Catholic Mariavite Church) – Maria Izabela Wiłucka-Kowalska and 11 nuns

- 1980: United Methodist Church – Marjorie Matthews

- 1988: Episcopal Church in the United States of America – Barbara Clementine Harris

- 1990: Anglican Church of New Zealand – Penelope Ann Bansall Jamieson

- 1990: Evangelical Lutheran Church in America – April Ulring Larson[57]

- 1992: North Elbian Evangelical Lutheran Church – Maria Jepsen

- 1993: Church of Norway (Lutheran) – Rosemarie Köhn

- 1993: Anglican Church of Canada – Victoria Matthews

- 1995: Church of Denmark (Evangelical Lutheran) – Lise-Lotte Rebel

- 1995: Church of Greenland - Sofie Petersen

- 1996: Church of Sweden (Evangelical Lutheran) – Christina Odenberg

- 1998: Moravian Church in America – Kay Ward

- 1998: United Church of Christ in the Philippines – Nelinda Primavera-Briones

- 1998: Presbyterian Church in Guatemala

- 1999: Czechoslovak Hussite Church – Jana Šilerová

- 1999: Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Hanover – Margot Käßmann

- 2000: African Methodist Episcopal Church – Vashti Murphy McKenzie

- 2001: Evangelical Church of Bremen – Brigitte Boehme, titled president, a laywoman since the presidency does not require theological skills

- 2001: North Elbian Evangelical Lutheran Church – Bärbel Wartenberg-Potter

- 2003: The Lutheran Evangelical Protestant Church (GCEPC) USA – Nancy K. Drew

- 2003: Church of Denmark (Evangelical Lutheran) - Elisabeth Dons Chritensen

- 2007: Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada – Susan Johnson

- 2008: Anglican Church of Australia – Kay Goldsworthy

- 2008: African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church – Mildred Hines

- 2009: Evangelical Church in Central Germany – Ilse Junkermann

- 2010: Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland – Irja Askola

- 2011: North Elbian Evangelical Lutheran Church – Kirsten Fehrs

- 2011: Evangelical Church of Westphalia – Annette Kurschus, titled praeses

- 2012: Church of Iceland (Lutheran) – Agnes M. Sigurðardóttir

- 2012: Anglican Church of Southern Africa – Ellinah Wamukoya

- 2012: Anglican Church of Southern Africa – Margaret Vertue[58]

- 2012: Church of Denmark – Tine Lindhardt[59]

- 2013: Church of Denmark – Marianne Christiansen[60]

- 2013: Church of Ireland (Anglican) – Pat Storey[61]

- 2013: Evangelical Lutheran Church of America – Elizabeth Eaton[62]

- 2014: Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia – Helen-Ann Hartley

- 2015: Church of England – Libby Lane

- 2015: Church of England – Alison White

- 2015: Church of England – Rachel Treweek

- 2015: Church of England – Sarah Mullally

- 2015: Church of England – Anne Hollinghurst

- 2015: Church of England – Ruth Worsley

- 2015: Church of England – Christine Hardman

- 2016: Church of England – Karen Gorham

- 2016: Church of England – Jo Bailey Wells

- 2016: Church of England – Jan McFarlane

- 2017: Church of England – Guli Francis-Dehqani

- 2017: Church in Wales – June Osborne

- 2017: Church of Denmark - Marianne Gaarden

- 2018: Scottish Episcopal Church – Anne Dyer

- 2018: Church in Wales – Joanna Penberthy

- 2019: Evangelical Church of Hesse Electorate-Waldeck – Beate Hofmann

- 2019: Evangelical Lutheran Church in Northern Germany – Kristina Kühnbaum-Schmidt

- 2020: Church of Greenland - Paneeraq Siegstad Munk

- Others: Protestant churches in German Lutheran, Reformed and United churches (EKD), Protestant Church of the Netherlands

Women as archbishops or denominational heads

- 1934 Salvation Army – Evangeline Booth General of The Salvation Army.

- 2004 Church of Scotland – Dr. Alison Elliot becomes moderator of the General Assembly

- 2005 Metropolitan Community Church – Nancy Wilson, first woman installed as moderator.

- 2006 The Episcopal Church—The Most Reverend Dr. Katharine Jefferts Schori. Installed as Presiding Bishop of the Episcopal Church and Primate (the same position which some other provinces in the Anglican Communion refer to as an Archbishop) at Washington National Cathedral on 4 November 2006, though she technically took office on the first of November.

- 2007 Evangelical Lutheran Church in Canada – Susan Johnson. First woman to serve as National Bishop of the ELCIC. She was consecrated 29 September 2007.

- 2013: Evangelical Lutheran Church of America – Elizabeth Eaton. First women installed as Presiding Bishop.[62]

- 2014 Church of Sweden – Antje Jackelén Archbishop of Uppsala. Installed in Uppsala Cathedral on 15 June 2014.

References

- "Women's Service in the Church: The Biblical Basis by N.T. Wright". Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Resolution on 50 Years of Women's Ordination in the Church of the Brethren" (PDF). www.brethren.org. 9 March 2008. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- http://www.mbconf.ca/home/products_and_services/resources/publications/mb_herald/vol_47_no_5/people_and_events/ordination_of_two_women_revives_discussion/

- https://bicus.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Women-Ministry-Leadership.pdf

- Thompsett, Fredrica Harris (2014). Looking Forward, Looking Backward: Forty Years of Women's Ordination. Church Publishing. ISBN 9780819229236.

- Kalvelage, david (1998). The Living Church, Volume 217. Morehouse-Gorham Company. p. 13.

- Jule, A. (2005). Gender and the Language of Religion. Springer. ISBN 9780230523494.

- "Bund Evangelisch-Freikirchlicher Gemeinden in Deutschland K.d.ö.R".

- Glenn T. Miller, Piety and Plurality: Theological Education since 1960, Wipf and Stock Publishers, USA, 2014, p. 94

- "沖縄バプテスト連盟". www.okinawa-baptist.asia. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- http://www.garbc.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/The-Ordination-of-Women-1975.pdf

- https://www.baptist.org.uk/Articles/370692/Women_Baptists_and.aspx

- Eroakirkosta.fi – Naispappeuskiista tuplannut kirkosta eroamisen

- "5.05 Naised vaimulikus ametis – Eesti Kirik". www.eestikirik.ee. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "ELCA Facts". ELCA.org. ELCA. Archived from the original on 20 September 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- "Presiding Bishop". ELCA.org. ELCA. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- "'She is loose': A historic group of female Lutheran bishops on #MeToo and the Holy Spirit". Religion News Service. 25 July 2018. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- "Becoming an LCMC Pastor 101 – LCMC". www.lcmc.net. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Constitution of the North American Lutheran Church" (PDF). 15 February 2016. p. 3.06. Retrieved 22 January 2019.

- http://lutheranmissions.org/the-position-of-women-in-the-church/

- "ELCT". www.elct.org.

- Frank Imhoff (19 June 2000). "wfn.org – Lutheran pastor becomes Ethiopia's first ordained woman". archive.wfn.org. Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- Rev. Patricia J. thompson, Courageous Past—Bold Future ISBN 0-938162-99-3

- Paramore the digital agency. "United Methodist Church Timeline – GCAH". www.gcah.org.

- "2010 New York Annual Conference Newsletter" (PDF).

- Communications, United Methodist. "Frequently Asked Questions about the Council of Bishops". The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- Communications, United Methodist. "Bishop Karen Oliveto". The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- "Discipline of the Primitive Methodist Church in the United States of America" (PDF). Primitive Methodist Church. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- The Discipline of the Evangelical Wesleyan Church. Evangelical Wesleyan Church. 2015. p. 115.

- "FMC Statement on Women in Ministry". Free Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- Sams, G. Clair (2017). "The Bible Methodist, Issue I, Volume 49" (PDF). Bible Methodist Connection of Churches. p. 2. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- https://secure.wesleyan.org/147/women-in-ministry-historical-view

- "Dienst der Frau-Frauenordination eingeführt". 2004.

- "Gereformeerde Bond | Gereformeerde Bond brengt brochure 'Geroepen vrouw' uit".

- "Women pastors from 1900 to 1960 – Musée virtuel du Protestantisme". Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Women's Ordination Time Line". Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- "Women's Ordination Time Line (page 2)". Retrieved 20 March 2007.

- What Presbyterians Believe Holper, J. Frederick, 2001 "What Presbyterians Believe about Ordination," Presbyterians Today, May 2001, retrieved from on 21 August 2006

- Hunter, Rashell. "PCUSA Celebrates 60 Years of Women Clergy". PCUSA.org. PCUSA.org. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- http://www.byfaithonline.com/partner/Article_Display_Page/0,,PTID323422%7CCHID664022%7CCIID2143300,00.html

- "PCA: Press Release".

- "Women in Ecclesiastical Office". Archived from the original on 26 July 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "NAPARC Votes, 6–1, to Suspend the Christian Reformed Church". Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- "Orthodox Presbyterian Church". Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Stocker, Abby. "Reformed Church of America Prevents Opposition to Women's Ordination". News & Reporting. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- "When churches started to ordain women". Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Pound, Richard W. (2005). Fitzhenry and Whiteside Book of Canadian Facts and Dates. Fitzhenry and Whiteside.

- Scheme of Union Archived 3 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine of the Presbyterian Church of Australia.

- Calvo, Janis (1974). "Quaker Women Ministers in Nineteenth Century America". Quaker History. 63 (2): 75–93. ISSN 0033-5053. JSTOR 41946743.

- Soderlund, Jean R. (October 1987). "Women's Authority in Pennsylvania and New Jersey Quaker Meetings, 1680–1760". The William and Mary Quarterly. 44 (4): 722–749. doi:10.2307/1939742. JSTOR 1939742.

- Larsen, Timothy; Ledger-Lomas, Michael (28 April 2017). The Oxford History of Protestant Dissenting Traditions, Volume III: The Nineteenth Century. Oxford University Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-150667-3.

- "Women in Ministry". www.cmalliance.org.

- "camacop.org.ph". camacop.org.ph.

- "Home" (PDF). CMACCD.

- "Women in ordained ministry". Archived from the original on 15 April 2009.

- "Women Ministers Allowed".

- http://www.vasynod.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/02/The-Rev-Dr-April-Ulring-Larson-Bishop-Emeritus.pdf

- "South Africa: Church Elects Woman Bishop". www.allAfrica.com. 4 October 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "interchurch.dk: Third woman bishop elected on Funen". interchurch.dk. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Marianne Christiansen bispeviet i Haderslev". folkekirken.dk. 4 March 2015. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Central Communications Board of the General Synod). "Church of Ireland – A province of the Anglican Communion". Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- "Presiding Bishop". ELCA.org. Retrieved 14 March 2015.