Julian of Norwich

Julian (or Juliana) of Norwich (1343[note 1] – after 1416), also known as Dame Julian or Mother Julian, was an English anchorite of the Middle Ages. She wrote the best known surviving book in the English language written by a mystic, Revelations of Divine Love. The book is the first written in English by a woman.

Julian of Norwich | |

|---|---|

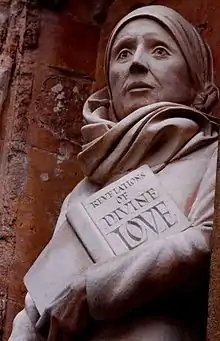

The statue of Julian of Norwich on the West Front of Norwich Cathedral, made by the sculptor David Holgate in 2014. | |

| Born | 1343 |

| Died | after 1416 (aged 73–74) |

| Occupation | theologian, anchoress, mystic |

Notable work | Revelations of Divine Love |

| Theological work | |

| Language | Middle English |

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

She lived practically her whole life in the English city of Norwich, an important centre for commerce that also had a vibrant religious life. During her lifetime, the city suffered the devastating effects of the Black Death of 1348–50; the Peasants' Revolt, which affected large parts of England in 1381; and the suppression of the Lollards. In 1373, aged thirty and so seriously ill she thought she was on her deathbed, Julian received a series of visions or "shewings" of the Passion of Christ. She recovered from her illness and wrote two versions of her experiences, the earlier one being completed soon after her recovery (however its manuscript clearly states it was written far later, in 1413, and when Julian was still alive), and a much longer version, today known as the Long Text, being written many years later.

For much of her life, Julian lived in permanent seclusion as an anchoress in her cell, which was attached to St Julian's Church, Norwich. Four wills in which sums were bequeathed to her have survived, and an account by the celebrated mystic Margery Kempe exists, which provides details of the counsel she was given by the anchoress.

Nothing is known for certain about Julian's actual name, family, or education, or of her life prior to her becoming an anchoress. Preferring to write anonymously, and seeking isolation from the world, she was nevertheless influential in her own lifetime. Her manuscripts were carefully preserved by Brigittine and Benedictine nuns, all the scribes but one being women.[2] The Protestant Reformation prevented their publication in print for a very long time. The Long Text was first published in 1670 by the Benedictine Serenus de Cressy, under the title XVI Revelations of Divine Love, shewed to a devout servant of Our Lord, called Mother Juliana, an Anchorete of Norwich: Who lived in the Dayes of King Edward the Third. Cressey's book was reissued by George Hargreaves Parker in 1843, and a modernised version of the text was published by J. T. Hecker in 1864. The work emerged from obscurity in 1901 when a manuscript in the British Museum was transcribed and published with notes by Grace Warrack. Since then many more translations of Revelations of Divine Love (also known under other titles) have been produced. Julian is today considered to be an important Christian mystic and theologian.

Background

_by_Woodward.jpg.webp)

The English city of Norwich, where Julian probably lived all her life, was second in importance to London during the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and at the centre of the country's primary region for agriculture and trade.[3][note 2] During her life Norwich suffered terribly when the Black Death reached the city. The disease may have killed over half the population and returned in subsequent outbreaks up to 1387.[3] Julian was alive during the Peasants' Revolt of 1381, when the city was overwhelmed by rebel forces led by Geoffrey Litster, later executed by Henry le Despenser after his peasant army was overwhelmed at the Battle of North Walsham.[5] As Bishop of Norwich, Despenser zealously opposed Lollardy, which advocated reform of the Catholic Church, and a number of Lollards were burnt at the stake at Lollard's Pit, just outside the city.[3]

Norwich may have been one of the most religious cities in Europe at that time, with its cathedral, friaries, churches and recluses' cells dominating both the landscape and the lives of its citizens. On the eastern side of the city was the Norman Cathedral (founded in 1096), the Benedictine Hospital of St. Paul, the Carmelite friary, St. Giles' Hospital, the Greyfriars monastery, and to the south the priory at Carrow, located just beyond the city walls.[6][7] The priory's income was mainly generated from 'livings' it acquired for renting its assets, which included the Norwich churches of St. Julian, All Saints Timberhill, St. Edward Conisford and St. Catherine Newgate, all now lost apart from St. Julian's. Where these churches had an anchorite cell, they enhanced the reputation of the priory still further, as they attracted legacies and endowments from across society.[8][9]

St Julian's Church

Julian is associated with St Julian's Church, Norwich, located off King Street in the south of the city centre, and which still holds services on a regular basis.[10] St. Julian's is an early round-tower church, one of the 31 surviving parish churches of a total of 58 that were built in Norwich after the Norman conquest of England.[11]

During the Middle Ages there were twenty-two religious houses in Norwich and sixty-three churches within the city walls, of which thirty-six had an anchorage.[12] No hermits or anchorites existed in Norwich from 1312 until the emergence of Julian in the 1370s.[13] It is not recorded when the anchorage at St. Julian's was built, but it was used by a number of different anchorites up to the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s, some of whom were named Julian. After this time the cell was demolished and the church stripped of its rood screen and statues. No rector was then appointed until 1581.[14]

By 1845 St. Julian's was in a very poor state of repair and that year the east wall collapsed. After an appeal for funds, the church underwent a ruthless restoration.[15][note 3] It was further restored in the 20th century,[17] but was destroyed during the Norwich Blitz of 1942, when in June that year the tower received a direct hit. After the war, funds were raised to rebuild the church. It now appears largely as it was before its destruction, although its tower is much-reduced in height and a chapel has been built in place of the long-lost anchorite cell.[18]

Life

Information available

_f._97r.png.webp)

Uniquely for the mystics of the Middle Ages, Julian wrote about her visions.[19] She was an anchoress from at least the 1390s,[20] and was the greatest English mystic of her age, by virtue of the visions she experienced and her literary achievement, but almost nothing about her life is known.[19] What little is known about her comes from a handful of sources. She provides a few scant comments about the circumstances of her revelations in her book Revelations of Divine Love,[20] of which one fifteenth-century manuscript and a number of longer, post-Reformation manuscripts, have survived.[19] The earliest surviving copy of Julian's Short Text, made by a scribe in the 1470s, acknowledges her as the author of the work.[20]

The earliest known reference to an anchorite living in Norwich with the name Julian comes from a will made in 1394.[20] There are four known wills which mention her, all of which were made by individuals living in Norfolk. Roger Reed, the rector of St Michael Coslany, Norwich, whose will of 20 March 1393/4 provides the earliest record of Julian's existence, made a bequest of 12 shillings to be paid to "Julian anakorite".[1] Thomas Edmund, a Chantry priest from the Norfolk town of Aylsham, stipulated in his will of 19 May 1404 that 12 pennies be given to "Julian, anchoress of the church of St. Julian, Conisford" and 8 pennies to "Sarah, living with her".[1][note 4] A Norwich man, John Plumpton, gave 40 pennies to "the anchoress in the church of St. Julian's, Conisford, and a shilling each to her maid and her former maid Alice", in his will dated 24 November 1415.[1] The fourth person to mention Julian was Isabelle, Countess of Suffolk (the second wife of William de Ufford, 2nd Earl of Suffolk), who made a bequest of 20 shillings to "a Julian reclus a Norwich" in her will dated 26 September 1416.[1] A bequest to an unnamed anchorite at St. Julian's was made in 1429, there is a possibility she was alive at this time.[13]

.png.webp)

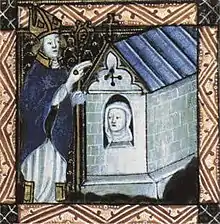

Julian was known as a spiritual authority within her community, where she also served as a counsellor and adviser.[22] In around 1414, when she was in her seventies, she was visited by the celebrated English mystic Margery Kempe. In The Book of Margery Kempe, which has been claimed to be the first ever autobiography to be written in English,[23] she wrote about going to Norwich to obtain spiritual advice from Julian,[24] saying she was "bidden by Our Lord" to go to "Dame Jelyan ... for the anchoress was expert in" divine revelations, "and good counsel could give".[25] Margery Kempe never referred to Julian as an author, although she was familiar with the works of other spiritual writers, and mentioned them.[13]

Visions

According to Julian's book Revelations of Divine Love, at the age of thirty, and when she was perhaps an anchoress already, Julian fell seriously ill. On 8 May 1373 a curate was administering the last rites of the Catholic Church to her, in anticipation of her death. As he held a crucifix above the foot of her bed, she began to lose her sight and feel physically numb, but gazing on the crucifix she saw the figure of Jesus begin to bleed. Over the next several hours, she had a series of fifteen visions of Jesus, and a sixteenth the following night.[26]

Julian completely recovered from her illness on 13 May. She wrote about her "shewings" shortly after she experienced them.[19] Her original manuscript no longer exists, but a copy survived, now referred to as her Short Text.[27] Twenty to thirty years later, perhaps in the early 1390s, she began a theological exploration of the meaning of her visions, now known as The Long Text. Consisting of eighty-six chapters and about 63,500 words,[28] this second work seems to have gone through many revisions before it was finished, perhaps in the 1410s or 1420s.[27]

Julian's revelations, which appear to have been the first of their kind to occur in England for two centuries, mark her as unique amongst medieval mystics.[19] It is possible she was a lay person living at home when her visions occurred,[29] as she was visited by her mother and other people shortly before her visions, and the rules of enclosure for an anchoress would not normally have allowed outsiders such access.[30]

Personal life

The few autobiographical details Julian included in the Short Text, including her gender, were suppressed when she wrote her longer text later in life.[31] Historians are not even sure of her actual name. It is generally thought to be taken from St. Julian's Church in Norwich, but it was also used in its own right as a girl's name in the Middle Ages, and so could have been her actual Christian name.[32]

Julian's writings indicate that she was born in 1343 or late 1342, and died after 1416.[33][1] She was six when the Black Death arrived in Norwich, which may have killed a third of the city's population.[34] It has been speculated that she was educated as a young girl by the Benedictine nuns of Carrow Abbey, as it is known that a school for girls existed there during her childhood.[35][33] Anchoresses did not usually have to come from a religious community, and it is unlikely that Julian ever became a nun.[36] There is no written evidence that she was ever a nun at Carrow Abbey during her lifetime,[29] and as she referred in her writings to being visited by her mother at her bedside, commentators have suggested that she was living at home when her visions occurred.[33]

According to several commentators, including Santha Bhattacharji in her article in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Julian's discussion of the maternal nature of God suggests that she knew of motherhood from her own experience of bringing up her own children.[29] As plague epidemics were rampant during the 14th century, it has been suggested that Julian may have lost her own family as a result of plague.[37][38] By then becoming an anchoress she would have been kept in quarantine away from the rest of the population of Norwich.[33] However, nothing in her writings provides any indication of the plagues, religious conflict, or civil insurrection that occurred in the city during her lifetime.[39] Kenneth Leach and Sister Benedicta Ward SLG, the joint authors of Julian Reconsidered (first published in 1988),[40] are of the opinion that she was a young widowed mother, and never a nun, based on a dearth of references about her occupation in life, and a lack of evidence to connect her with Carrow Priory, which would have honoured her, and buried her in the priory grounds.[41]

Life as an anchoress

As an anchoress, Julian would have played an important part within her community, devoting herself to a life of prayer to complement the clergy in their primary function as protectors of people's souls.[42] Her solitary life would have begun upon the completion of an elaborate selection process.[43] An important church ceremony would have taken place at St. Julian's Church, in the presence of the Bishop of Norwich.[44] During the ceremony, psalms from the Office of the Dead would have been sung for her, as if it were her own funeral, and at some point Julian would have been led to her cell door and into the room beyond.[45] The door would afterwards have been sealed up, and she would have remained in her cell for the rest of her life.[46]

Once her life of seclusion had begun, Julian would have had to follow the strict rules for anchoresses. Two important sources of information about the life led by an anchoress have survived. De institutione inclusarum was written in Latin by Ælred of Rieveaulx in c. 1162, and the Ancrene Riwle was written in Middle English in c. 1200.[47][note 5] Although originally made for three religious sisters to follow, The Ancrene Riwle became in time a manual for all female recluses.[48] The work regained its former popularity during the mystical movement of the fourteenth century and may have been available to Julian in a version she could read and become familiar with.[49] It stipulated that anchoresses lived a life of confined isolation, poverty, and chastity.[50] However, some anchoresses are known to have lived comfortably, and there are instances in which they shared their accommodations with fellow recluses.[51]

The popular image of Julian living with her cat for company stems from the regulations set out in The Ancrene Riwle.[51]

As an anchoress living in the heart of an urban environment, Julian would not have led an entirely secluded life. She would have been permitted to make clothes for the poor, and she enjoyed the financial support of the more prosperous members of the local community, as well as the general affection of the population.[52] She would have in turn provided prayers, advice and counsel to the people, serving as an example of devout holiness.[52]

According to one edition of the Cambridge Medieval History, it is possible that she met the English mystic Walter Hilton, who died when she was in her fifties and who may have influenced her writings in a small way.[53]

Revelations of Divine Love

.jpg.webp)

Julian of Norwich was, according to the historian Henrietta Leyser, "beloved in the twentieth century by theologians and poets alike".[54] Her writings are unique, as no other works by an English anchoress have survived, although it is possible that some anonymous works may have been written by women. In 14th century England, when women were generally barred from high status positions, their knowledge of Latin would have been limited, and it is more likely that they read and wrote in English.[48] The historian Janina Ramirez has suggested that by choosing to write in her vernacular language, a precedent set by other medieval writers, Julian was "attempting to express the inexpressible" in the best way possible.[55] Nothing written by Julian was ever mentioned in any bequests, nor written for a specific readership, or influenced other medieval authors,[56] and almost no references were made of her writings from the time they were written until the beginning of the 20th century.[57]

Julian was largely unknown until 1670, when her writings were published under the title XVI Revelations of Divine Love, shewed to a devout servant of Our Lord, called Mother Juliana, an Anchorete of Norwich: Who lived in the Dayes of King Edward the Third by Serenus de Cressy, a confessor for the English nuns at Cambrai.[58][13] Cressy, who knew nothing of Julian's earlier Short Text, based his book on the Long Text,[59] developed by her over a number of years, of which three manuscript copies survive.[60]One copy of the complete Long Text, known as the Paris Manuscript, resides in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. Two other manuscripts are now in the British Library.[61] One of the manuscripts was perhaps copied out by Dame Clementina Cary, who founded the English Benedictine monastery in Paris.[57]

Cressy's edition was reprinted in 1843, 1864 and again in 1902.[62]

Modern interest in Julian's book increased when Henry Collins published a new version of the book in 1877.[63] It became known still further after the publication of Grace Warrack's 1901 edition, which included modernised language, as well as, according to the author Georgia Ronan Crampton, a "sympathetic informed introduction".[63] The book introduced most early 20th century readers to Julian's writings.[63]

Julian's shorter work, which may have been written not long after Julian's visions in May 1373, is now known as her Short Text.[64] As with the Long Text, the original manuscript was lost, but not before at least one copy was made by a scribe, who named Julian as the author.[65] It was in the possession of an English Catholic family at one point.[57] The copy was seen by the antiquarian Francis Blomefield in 1745,[66][67] After disappearing from view for 150 years, it was found in 1910, in a collection of contemplative medieval texts bought by the British Museum.[68] It was published by Reverend Dundas Harford in 1911.[66] Now part of MS Additional 37790, the manuscripts are held in the British Library.[69]

Long Text

- "MS Fonds Anglais 40 (previously Regius 8297): Liber Revelacionum Julyane, anachorite norwyche, divisé en quatre-vingt-six chapitres". Archives et manuscrits. BnF (Bibliothèque nationale de France), Paris. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "Sloane MS 2499: Juliana, Mother, Anchorite of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love, 1373". Explore Archives and Manuscripts. British Library, London.

- "Sloane MS 3705: Visions: Revelations to Mother Juliana in the year 1373 of the love of God in Jesus Christ". Explore Archives and Manuscripts. British Library, London.

- Westminster Cathedral Treasury MS 4 (written c.1450), now on loan to Westminster Abbey's Muniments Room and Library. The manuscript includes extracts from Julian's Long Text, as well as selections from the writings of the English mystic Walter Hilton.

Short Text

- "Add MS 37790 (An anthology of theological works in English (the Amherst Manuscript))". Digitised Manuscripts. British Library.

Theology

Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love.[70]

Julian of Norwich is now recognised as one of England's most important mystics.[71]

For the theologian Denys Turner the core issue Julian addresses in Revelations of Divine Love is "the problem of sin". Julian says that sin is behovely, which is often translated as 'necessary', 'appropriate', or 'fitting'.[72][73]

Julian lived in a time of turmoil, but her theology was optimistic and spoke of God's omnibenevolence and love in terms of joy and compassion. Revelations of Divine Love "contains a message of optimism based on the certainty of being loved by God and of being protected by his Providence."[74]

The most characteristic element of her mystical theology was a daring likening of divine love to motherly love, a theme found in the Biblical prophets, as in Isaiah 49:15.[74][75] According to Julian, God is both our mother and our father. As Caroline Walker Bynum showed, this idea was also developed by Bernard of Clairvaux and others from the 12th century onward.[76] Some scholars think this is a metaphor rather than a literal belief.[77] In her fourteenth revelation, Julian writes of the Trinity in domestic terms, comparing Jesus to a mother who is wise, loving and merciful. F. Beer asserted that Julian believed that the maternal aspect of Christ was literal and not metaphoric: Christ is not like a mother, he is literally the mother.[78] Julian emphasized this by explaining how the bond between mother and child is the only earthly relationship that comes close to the relationship a person can have with Jesus.[79] She used metaphors when writing about Jesus in relation to ideas about conceiving, giving birth, weaning and upbringing.[80]

She wrote, "For I saw no wrath except on man's side, and He forgives that in us, for wrath is nothing else but a perversity and an opposition to peace and to love."[81] She wrote that God sees us as perfect and waits for the day when human souls mature so that evil and sin will no longer hinder us.[82] "God is nearer to us than our own soul," she wrote. This theme is repeated throughout her work: "Jesus answered with these words, saying: 'All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well.' ... This was said so tenderly, without blame of any kind toward me or anybody else".[83]

Monastic and university authorities might not have challenged her theology because of her status as an anchoress.[84] A lack of references to her work during her own time may indicate that she kept her writings with her in her cell, so that the religious authorities were unaware of them.[85]

The revival of interest in her has been associated with a renewed interest in the English-speaking world in Christian contemplation.[86] The Julian Meetings, an association of contemplative prayer groups, takes its name from her, but is otherwise unconnected with Julian's theology.[87]

Adam Easton's Defense of St Birgitta, Alfonso of Jaen's Epistola Solitarii, and William Flete's Remedies against Temptations, are all used in Julian's text.[88]

Commemoration

Since 1980, Julian has been commemorated in the Anglican Church with a feast day on 8 May.[89][90] The Episcopal Church and the Evangelical Lutheran Church also commemorate her on 8 May.[91][92]

She has not been formally beatified or canonised in the Roman Catholic Church, so she is not currently listed in the Roman Martyrology or on the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church in England and Wales.[93][94] However, she is popularly venerated by Catholics as a holy woman of God, and is therefore at times referred to as "Saint", "Blessed", or "Mother" Julian.[74][95][96] Julian's feast day in the Roman Catholic tradition (by popular celebration) is on 13 May.[97]

In 1997, Father Giandomenico Mucci reported that Julian of Norwich is on the waiting list to be declared a Doctor of the Church.[98] In light of her established veneration, it is possible she will first be given an 'equivalent canonization', in which she is decreed a saint by the Pope, without the full canonization process being followed.[99][100]

At a General Audience on 1 December 2010, Pope Benedict XVI discussed the life and teaching of Julian. "Julian of Norwich understood the central message for spiritual life: God is love and it is only if one opens oneself to this love, totally and with total trust, and lets it become one's sole guide in life, that all things are transfigured, true peace and true joy found and one is able to radiate it," he said. He concluded: "'And all will be well,' 'all manner of things shall be well': this is the final message that Julian of Norwich transmits to us and that I am also proposing to you today."[101]

Legacy

Literature

The Catechism of the Catholic Church quotes from Revelations of Divine Love in its explanation of how God can draw a greater good, even from evil.[102][103] Pope Benedict XVI dedicated his general audience catechesis of 1 December 2010 to Julian of Norwich.[74]

The poet T. S. Eliot incorporated "All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well", as well as Julian's "the ground of our beseeching" from her fourteenth revelation into his poem "Little Gidding", the fourth of his Four Quartets (1943).[104] "Little Gidding" raised the public's awareness of Julian's texts for the first time.[105] Sydney Carter's song "All Shall Be Well" (sometimes called "The Bells of Norwich"), which uses words by Julian, was released in 1982.[106]

Julian's writings have been translated into numerous languages, including Russian.[107]

Julian in Norfolk and Norwich

In 2013 the University of East Anglia honoured Julian by naming its new study centre the Julian Study Centre.[108]

Norwich's Julian Week, an annual celebration of Julian, was begun in 2013. Organised by The Julian Centre, events held around the city included concerts, lectures, workshops and tours, with the stated aim of "educating all interested people about Julian of Norwich" and "presenting her as a cultural, historical, literary, spiritual, and religious figure of international significance".[109]

The Lady Julian Bridge, crossing the River Wensum, linking King Street and the Riverside Walk close to Norwich railway station, was named in honour of the anchoress. An example of a swing bridge, built to allow larger vessels to approach a basin further upstream, it was designed by the Mott MacDonald Group and completed in 2009.[110]

Julian's self-isolation

In March 2020, during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, Julian's relevance to people around the world who are self-isolating was highlighted.[111] Janina Ramirez was quoted by BBC News, saying that "Julian was living in the wake of the Black Death, and around her repeated plagues were re-decimating an already depleted population. I think she was self-isolating. The other anchorites would have understood that by removing themselves from life this would not only give them a chance of preserving their own life but also of finding calm and quiet and focus in a chaotic world."[112]

Notes

- Sources do not all agree on the year that Julian of Norwich was born; Windeatt gives late 1342.[1]

- A lack of data about Norwich's population during this period in its history means that it is not known for certain that the city ranked as second in size after London, although Norwich was recorded as having 130 individual trades at the end of the 13th century, in comparison with 175 for London, and more than any other regional centre in England.[4]

- According to the author Sheila Upjohn and the church historian Nicholas Groves, "The restoration of the church, when [the rector] was finally forced to take action after half a century of neglect, was ruthless to the point of vandalism".[16]

- It has been assumed by the historian Janina Ramirez that Sarah was Julian's maid, and her link to the outside world.[1] According to Ramirez, she probably had access to Julian by means of a smaller adjoining room.[21]

- Apart from The Ancrene Riwle and De institutione inclusarum, the most important of the thirteen surviving texts are Richard Rolle's Form of Living (c. 1348) and The Scale of Perfection (written by Walter Hilton in 1386 and later prior to his death in 1396).[20]

References

- Windeatt 2015, p. xiv.

- Holloway 2008, pp. 269–324.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 17.

- Rawcliffe & Wilson 2004, p. 158.

- Ramirez 2016, pp. 25–6.

- Windeatt 2015, pp. xxxiii–iv.

- Rawcliffe & Wilson 2004, p. 88.

- Rawcliffe & Wilson 2004, p. 89.

- Jones, E.A. "The Hermits and Anchorites of Oxfordshire" (PDF). Oxoniensia. pp. 56–7. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "Norwich: St Julian". A Church Near You. Church of England. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- "Welcome". The Medieval Churches of Norwich. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Upjohn & Groves 2018, p. 12.

- Crampton, Georgia Ronan (1994). "The Shewings of Julian of Norwich: Introduction". Middle English Text Series. New York: University of Rochester. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Upjohn & Groves 2018, pp. 12–15.

- Upjohn & Groves 2018, pp. 17–18.

- Upjohn & Groves 2018, p. 18.

- Upjohn & Groves 2018, p. 27.

- Upjohn & Groves 2018, p. 28.

- Leyser 2002, p. 219.

- Baker 1993, p. 148.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 18.

- "Juliana of Norwich -". projectcontinua.org. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "Margery Kempe, the first English autobiographer, goes online". The Guardian. 2014. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- Windeatt 2015, p. viii.

- Butler-Bowden & Chambers 1954, p. 54.

- Windeatt 2015, p. ix.

- McGinn 2012, p. 425.

- Jantzen 2011, pp. 4–5.

- Bhattacharji 2014.

- Windeatt 2015, p. xv.

- Windeatt 2015, p. xiii.

- Groves 2010, p. 74.

- Beer 1992, p. 130.

- Upjohn & Groves 2018, p. 13.

- Watson & Jenkins 2006.

- Leyser 2002, p. 208.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 25.

- Obbard 2008, p. 16.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 31.

- Julian reconsidered. OCLC 20029148.

- Leech & Ward 1995, p. 21.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 9.

- Leyser 2002, p. 206.

- Rolf 2018, p. 50.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 13.

- Ramirez 2016, pp. 5, 13.

- Leyser 2002, pp. 210, 212.

- Leyser 2002, p. 212.

- Baker 1993, p. 149.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 11.

- Ramirez 2016, pp. 11–13.

- Windeatt 2015, pp. xii–xiii.

- Cambridge Medieval History, vol. 7, p. 807.

- Leyser 2002, pp. 218–9.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 7.

- Rolf 2013, p. 8.

- Leech & Ward 1995, p. 12.

- "Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love (Stowe MS 42: c 1675)". Explore Archives and Manuscripts. British Library. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 78.

- Windeatt 2015, p. xx.

- Crampton 1993, p. 17.

- XVI Revelations of Divine Love. WorldCat. OCLC 606570496.

- Crampton 1993, p. 18.

- Windeatt 2015, p. xxi.

- Ramirez 2016, pp. 74–5.

- Rolf 2013, p. 9.

- Blomefield & Parkin 1805, p. 81.

- Rolf 2013, p. 6.

- Windeatt 2015, pp. li, lii.

- Leyser 2002, p. 220.

- Pelphrey 1989, p. 14.

- Watson & Jenkins 2006, p. 208.

- Turner 2011.

- Pope Benedict XVI. General Audience, 1 December 2010

- Isaiah 49:15, NAB

- Bynum 1984, pp. 111–2.

- Bynum 1984, p. 130.

- Beer 1992, p. 152.

- Beer 1992, p. 155.

- D-Vasilescu 2018, p. 13.

- Beer 1998, p. 45.

- Beer 1998, p. 50.

- Skinner 1997, pp. 54–55, 124.

- Ramirez 2016, pp. 8–9.

- Ramirez 2016, p. 32.

- "The Julian Meetings – History". Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "The Julian Meetings – About meetings". Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Holloway 2016, pp. 97–146.

- "The Calendar". The Church of England. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Windeatt 2015, p. xlviii.

- "Dame Julian of Norwich, c. 1417". Episcopal Church. 5 July 2011. Archived from the original on 16 October 2018. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Of the world but cloistered". Living Lutheran. Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. 9 May 2014. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Martyrologium Romanum. Typis Vaticanis. 2004.

- "Liturgy Office of England and Wales, Calendar 2017". liturgyoffice.org.uk. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- "Blessed Julian of Norwich". CatholicSaints.Info. 3 May 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Morning Offering | A Daily Catholic Devotional Email". Morning Offering. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Online, Catholic. "St. Juliana of Norwich – Saints & Angels – Catholic Online". Catholic Online. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- "Vatican Diary / A new doctor of the Church. And seventeen more on hold". chiesa.espresso.repubblica.it. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Benedict XVI formally recognises Hildegard of Bingen as a saint | CatholicHerald.co.uk". CatholicHerald.co.uk. 11 May 2012. Archived from the original on 14 May 2012. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "What is an equivalent canonization?". romereports.com. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- BENEDICT XVI , GENERAL AUDIENCE, Paul VI Hall, Wednesday, 1st December 2010, with video

- "Catechism of the Catholic Church – The Creator". vatican.va. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Divine Providence", Catechism of the Catholic Church, 2nd ed., §313, Libreria Editrice Vaticana

- Newman 2011, p. 427.

- Leech & Ward 1995, p. 1.

- "All Shall Be Well – Carter". GodSongs.net. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Dresvina 2010.

- "Lord Mayor raises a glass to new UEA building". Archive of Press Releases. University of East Anglia. 14 June 2013. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- "Julian Week 2014". The Julian Centre. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2018.

- "A Walk along the River Wensum in Norwich, looking at the City's Historic Bridges". Institute of Civil Engineers. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- Perk, Godelinde Gertrude (27 March 2020). "Coronavirus: advice from the Middle Ages for how to cope with self-isolation". The Conversation. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Rigby, Nic (30 March 2020). "Coronavirus: Mystic's 'relevance' to self-isolating world". BBC News. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

Sources

- Baker, Denise N. (September 1993). "Julian of Norwich and Anchoritic Literature". Mystics Quarterly. 19 (4): 148–161. (registration required)

- Beer, Frances (1992). Women and Mystical Experience in the Middle Ages. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-302-5.

- Beer, Frances (1998). Jullian of Norwich - Revelations - Motherhood of God. Cambridge: Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-0-85991-453-6. Archived from the original on 28 March 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Bhattacharji, Santha (2014). "Julian of Norwich (1342–c.1416)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15163. (subscription may be required or content may be available in libraries)

- Blomefield, Francis; Parkin, Charles (1805) [First published 1739-75]. An essay towards a topographical history of the county of Norfolk. Volume 4. London: Printed for W. Miller. OCLC 560883605.

- Butler-Bowden, W.; Chambers, R.W. (1954). The Book Of Margery Kempe. Oxford University Press. OCLC 3633095.

- Bynum, Caroline Walker (1984). Jesus as mother : studies in the spirituality of the High Middle Ages. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05222-2.(registration required)

- Crampton, Georgia Ronan (1993). The Shewings of Julian of Norwich. Western Michigan University: Kalamazoo. ISBN 978-1-879288-45-4. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- Dresvina, Juliana (2010). Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love. Moscow. ISBN 978-5-91244-031-1.

- D-Vasilescu, Elena Ene (2018). Heavenly Sustenance in Patristic Texts and Byzantine Iconography: Nourished by the Word. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-98985-3.

- Groves, Nicholas (2010). The Medieval Churches of the City of Norwich. Norwich: Norwich Heritage Economic and Regeneration Trust (HEART) and East Publishing. ISBN 978-0-9560385-2-4.

- Holloway, Julia Bolton (2008). Anchoress and Cardinal: Julian of Norwich and Adam Easton, O.S.B. Salzburg: Institut für Anglistik und Amerikanistik. ISBN 978-3-902649-01-0.

- Holloway, Julia Bolton (2016). Julian among the Books: Julian of Norwich's Theological Library. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4438-8894-3.

- Jantzen, Grace Marion (2011). Julian of Norwich: Mystic and Theologian. London: SPCK. ISBN 978-0-281-06424-3.

- Leech, Kenneth; Ward, Sr Benedicta SLG (1995). Julian Reconsidered. Oxford: SLG Press. ISBN 978-0-7283-0122-1.

- Leyser, Henrietta (2002). Medieval Women: a Social History of Women in England 450-1500. London: Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-84212-621-9.

- McGinn, Bernard (2012). The Varieties of Vernacular Mysticism 1350-1550. New York: Herder & Herder. ISBN 978-0-8245-4392-1.

- Newman, Barbara (2011). "Eliot's Affirmative Way: Julian of Norwich, Charles Williams, and Little Gidding". Modern Philology. 108 (3): 427–61. doi:10.1086/658355. ISSN 0026-8232. JSTOR 10.1086/658355. S2CID 162999145.

- Obbard, Elizabeth Ruth (2008). Through Julian's Windows: Growing into wholeness with Julian of Norwich. Norwich: Canterbury Press. ISBN 978-1-85311-903-3.

- Pelphrey, Brant (1989). Christ our mother: Julian of Norwich. Wilmington, Delaware: Glazier. ISBN 978-0-89453-623-6.

- Ramirez, Janina (2016). Julian of Norwich: A very brief history. London: SPCK. ISBN 978-0-281-07737-3.

- Rawcliffe, Carol; Wilson, Richard, eds. (2004). Medieval Norwich. London, New York: Hambleton and London. ISBN 978-1-85285-449-2.

- Rolf, Veronica Mary (2013). Julian's Gospel: Illuminating the Life & Revelations of Julian of Norwich. Orbis Books. ISBN 978-1-62698-036-5.

- Rolf, Veronica Mary (2018). An Explorer's Guide to Julian of Norwich. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 978-0-8308-5088-4.

- Turner, Denys Alan (2011). Julian of Norwich, Theologian. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-16391-9.

- Upjohn, Sheila; Groves, Nicholas (2018). St Julian's Church Norwich. Norwich: The Friends of Julian of Norwich. ISBN 978-0-954-15246-8.

- Watson, Nicholas; Jenkins, Jacqueline (2006). The Writings of Julian of Norwich: A Vision Showed to a Devout Woman and A Revelation of Love. Penn State University Press. ISBN 978-0-271-02908-5.

Further reading

- Salih, Sarah; Baker, Denise Nowakowski, eds. (2009). Julian of Norwich's legacy: medieval mysticism and post-medieval reception. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-23-010162-3.

- Tanner, J.R.; Previté-Orton, C.W.; Brooke, Z.N., eds. (1932). Cambridge Medieval History. Volume VII. Cambridge University Press.

Selected editions of Revelations of Divine Love

- Cressy, R.F.S. (1670). "XVI Revelations of Divine Love, shewed to a devout servant of Our Lord, called Mother Juliana, an Anchorete of Norwich: Who lived in the Dayes of King Edward the Third". British Library Digitised Books. British Library. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- Collins, Henry, ed. (1877). Revelations of divine love, shewed to a devout Anchoress, by name Mother Julian of Norwich. London: T. Richardson.

- Warrack, Grace, ed. (1901). Revelations of Divine Love, Recorded by Julian, Anchoress at Norwich, 1373 (1st ed.). London: Methuen and Company. OCLC 560165491. (The second edition (1907) is available online from the Internet Archive

.)

.) - Skinner, John, ed. (1997). Revelation of love. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-48756-6.

- Beer, Frances, ed. (1998). Revelations of divine love, translated from British Library Additional MS 37790 : the motherhood of God : an excerpt, translated from British Library MS Sloane 2477. Rochester, NY: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85991-453-6.

- Reynolds, Anna Maria and; Julia Bolton Holloway, eds. (2001). Showing of Love: Extant Texts and Translations. Florence: SISMEL: Edizioni del Galluzzo. ISBN 978-88-8450-095-3.

- Starr, Mirabai (2013). The Showings of Julian of Norwich: A New Translation. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-57174-691-7.

- Windeatt, Barry, ed. (2015). Revelations of Divine Love. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-811206-8.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Julian of Norwich |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Julian of Norwich. |

- The Julian Centre, official website of the centre devoted to Julian, located next to St. Julian's Church, Norwich. The website contains information about the Companions of Julian.

- Julian of Norwich: her Showing of Love and its Context produced by the Umilta website.

- "Julian of Norwich" from the Luminarium Encyclopedia project on English literature.

- The Search for the Lost Manuscript, a BBC documentary on YouTube about Julian of Norwich, her writings and how her writings survived to be become published books.

- Heart and Soul: The Path of Love – Julian of Norwich from BBC Sounds, a short radio programme about Julian and her writings. (registration required, may not be available outside the UK)

- Works by Julian of Norwich at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Julian of Norwich at Internet Archive

- Works by Julian of Norwich at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)