Otto Smik

Otto Smik DFC (20 January 1922 – 28 November 1944) was a Czechoslovak pilot who became a fighter ace in the Royal Air Force. He joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve in July 1940 and was in training until the end of 1942. Between March 1943 and June 1944 he shot down 13 Luftwaffe fighter aircraft probably shot down one more and shared in the shooting down of two others. In July 1944 he shot down three V-1 flying bombs.

Otto Smik | |

|---|---|

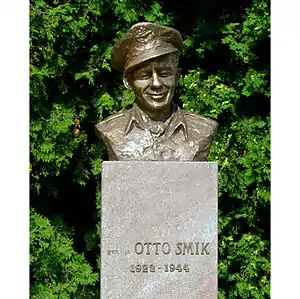

Monument to Otto Smik in Sliač, Slovakia | |

| Born | 20 January 1922 Borjomi, Georgian SSSR |

| Died | 28 November 1944 (aged 22) Ittersum, Netherlands |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | Czechoslovak Army Royal Air Force |

| Years of service | 1940–44 |

| Rank | Squadron Leader |

| Service number | 130678 |

| Unit | No. 312 Squadron RAF No. 310 Squadron RAF |

| Commands held | "B" Flight, No. 312 Sqn RAF No. 127 Squadron RAF |

| Battles/wars | Second World War |

| Awards |

|

Smik was born in the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic to a Slovak father and a Russian Jewish mother. When he was 12 the Smik family moved to Slovakia. He was the highest-scoring Slovak fighter ace in the RAF.

In October 1944 Smik survived being shot down behind enemy lines in the Netherlands, successfully evaded capture and returned to Allied-held territory. In November 1944 the RAF promoted him to Squadron Leader and put him in command of No. 312 (Czechoslovak) Squadron RAF. On 28 November he was shot down again over the German-held territory in the Netherlands and was killed.

Early life

Smik was born in Borjomi, a spa town in the Georgian SSSR. His father Rudolf Smik was a Slovak from Tisovec who had served in the Royal Hungarian Honvéd in the First World War, been captured by the Imperial Russian Army and interned at Borjomi as a prisoner of war.[1]

Smik's mother Antonia (née Davydova) was the daughter of a Russian army officer who had guarded Rudolf Smik. After the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk Rudolf and Antonia were married and the couple lived in Borjomi[1] in the briefly-independent Democratic Republic of Georgia, which in 1921 was taken over by the Bolsheviks and became part of the Soviet Union in 1922.

Antonia bore Rudolf Smik three sons, of whom Otto was the second. Smik grew up fluent in Russian and Georgian and with some knowledge of Hungarian. (Tisovec had been in the Hungarian part of Austria-Hungary when his father lived there.) In 1934 the Smik family moved to Czechoslovakia, initially to Hájniky near Sliač in central Slovakia and then to Bratislava.[1]

Smik learnt Slovak, which he spoke with a Russian accent. He also learnt English. As a child his hobby was aeromodelling. As a teenager he became a glider pilot, and by the age of 17 he had completed 22 flying hours. From 1937 to 1939 he trained at a private business school. He then got a job as a clerk in the head office of a power station in Bratislava.[1]

Battle of France

On 15 March 1939 Nazi Germany partitioned the Second Czechoslovak Republic. Bratislava remained the capital of the Slovak Republic, which became a client state of Germany. Smik decided to escape to France to fight Germany. On 18 March 1940 he crossed illegally into Hungary, planning to reach the French Consulate in Budapest. Hungarian authorities arrested him and detained him in Toloncház prison, but was soon released.[1]

Smik obtained a false passport and joined 12 other Czechoslovak refugees. People smugglers got them into Yugoslavia by helping them to cross the River Drava near Terezino Polje in Sava Banovina. They reached Zagreb, where they joined a larger group of Czechoslovak refugees. The group travelled through Bulgaria to Thessaloniki in Greece, whence they went by train to Istanbul in Turkey. There they crossed the Bosphorus and continued by train to Beirut in French-ruled Lebanon. There they embarked on the Messageries Maritimes passenger ship Mariette Pacha which took them to Marseille in France.[1]

By now Germany had conquered the Netherlands and Belgium and reached the River Somme in northern France. Smik and his compatriots disembarked in Marseille in the south of France just as Operation Dynamo was evacuating encircled British, French and Belgian troops from Dunkirk in the north.

On 3 June 1940 Smik joined the Czechoslovak Army, which the Czechoslovak government-in-exile had reconstituted in France since October 1939. He was posted to a Czechoslovak training unit in Agde on the coast of Languedoc, where he applied to transfer to the Czechoslovak Air Force group in the French Armée de l'Air.[1]

But the Armée de l'Air was now fighting the Luftwaffe's increasing air supremacy and had no spare resources to train any more Czechoslovak recruits. On 5 June German forces launched Fall Rot to advance west and south from the Somme, and on 22 June France capitulated. Czechoslovaks based in Agde evacuated 30 km (19 mi) west to Vendres, where on 24 June the Elder Dempster Lines ship Apapa rescued them. The ship brought them to Liverpool in England on 7 July.[1]

Royal Air Force

Years of training

Many of the RAF Volunteer Reserve's new Czechoslovak recruits had qualified as pilots with the Czechoslovak Air Force and then retrained on modern French or American fighters with the French Armée de l'Air. Some had fought in the Battle of France and a few had previously fought in the Invasion of Poland. The RAF was able quickly to teach these experienced pilots about RAF structures and tactics, give them conversion training to fly and fight using RAF aircraft. Many were ready to be posted to combat squadrons within weeks of enlisting.

But Smik had only been a civilian glider pilot. On 24 July 1940 he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve as an Aircraftman 2nd Class. He then spent almost two and a half years in training. His first few months were as a batman at the RAF's new central training depôt for Czechoslovak recruits, which was at RAF Cosford in Shropshire. In March 1941 he was promoted to Leading Aircraftman and posted to No. 1 Reception Wing at Babbacombe in Devon to start training to be a pilot. From June to September 1941 he was at No. 4 Initial Training Wing at Paignton.[1]

From September to the end of November he was in a group of Czechoslovak trainees at No. 3 Elementary Flying Training School, where they learnt to fly the de Havilland Tiger Moth II. At the end of November four of them completed the course and went to RAF Clyffe Pypard in Wiltshire for further Tiger Moth training. At the end of 1941 they sailed to Canada for training at No. 39 Service Flying Training School at Swift Current airfield in Saskatchewan under the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan. Smik completed his course, rated as an "excellent" pupil.[1]

In 1942 Smik and his group then waited at No. 3 Personnel Reception Centre at Moncton, New Brunswick for a ship back to the UK. Smik returned to Britain in July. He then had further training at No. 5 Advanced Training Unit at RAF Ternhill in Shropshire and final training to become a fighter pilot at No. 61 Operational Training Unit. Also in 1942 Smik was commissioned as a Pilot Officer.[1]

Friction

On 5 January 1943 Smik was finally posted to an operational unit: No. 312 (Czechoslovak) Squadron RAF at RAF Church Stanton in Somerset. But he lasted only a week there before being transferred to a different Czechoslovak unit, No. 310 Squadron RAF.[1]

.jpg.webp)

Some of the more experienced Czechoslovak pilots quickly resented Smik. Many had fought in the Battle of France and some had fought in the RAF from the Battle of Britain onwards. Some had first fought in the defence of Poland in September 1939. They had many flying hours' of operation experience, had frequently been in combat, but many of them were still only sergeants. Smik was younger than they, had no combat experience, had only just qualified to fly a Supermarine Spitfire but was already an officer.[1]

Smik responded by requesting a transfer to a non-Czechoslovak squadron. The RAF agreed, and on 15 January sent him to No. 131 Squadron RAF, which at the time was at RAF Castletown in Caithness, Scotland for a period of rest and recuperation. But then in March 1943 Smik was transferred again, to No. 122 Squadron RAF at RAF Hornchurch in Essex.[1]

Spitfire ace

.jpg.webp)

At the time 122 Squadron was operating the Spitfire Mk IXC, with which it escorted bombers over German-occupied Europe. On 13 March 1943 Smik achieved his first "probable" shooting down of an enemy aircraft: a Messerschmitt Bf 109G-4 over Lumbres in the Pas-de-Calais. On 29 April No. 222 Squadron RAF arrived at Hornchurch, and on 18 May 122 Squadron moved to RAF Eastchurch in Kent for R&R. But Smik was still a fresh arrival, so he was transferred to 222 Squadron in order to remain at Hornchurch.[1]

With 222 Squadron Smik became a fighter ace. On 15 July 1943 he shot down a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A-4 near Le Crotoy on the Baie de Somme. It was the first of 10½ enemy aircraft that he shot down between then and 27 September: five Fw 190s, five Bf 109s plus a shared victory when he and a South African pilot, Flight Lieutenant J Lardner-Burke DFC, brought down a Bf 109G-6 near Boulogne-sur-Mer on 8 September.[1]

Smik acquired a reputation as a talented and aggressive pilot who took every opportunity to attack the enemy. He was the RAF's highest-scoring Czechoslovak pilot for the year 1943. On 1 November he was posted to the Central Gunnery School to be trained as in instructor. In the same month he was awarded the DFC. On 12 December he completed his course and was posted to No. 13 Armament Practice Camp at RAF Llanbedr in Merionethshire, Wales.[1]

After four years of war many RAF airmen had been killed, captured or too badly wounded to resume flying. The RAF tried to attract Czech and Slovak Americans and Czech and Slovak Canadians to join its Czechoslovak squadrons, but with little success. So on 15 March 1944 Smik was recalled to combat service.[1]

Smik's posting was to 310 Squadron, where his fellow-Czechoslovaks had made him so unwelcome 14 months earlier. But in the meantime he had won 10½ victories and a DFC, and many of the sergeants who had resented him had been commissioned as officers. From 28 March to 3 April Smik received a week's fighter-bomber training at Southend in Essex. By June 310 Squadron was based at RAF Appledram in West Sussex, where it provided air cover for the Allied Invasion of Normandy. On 8 June Smik shot down a Focke-Wulf Fw 190 A fighter near Lisieux. On 17 June he shot down another near Caen. Also he and another 310 Squadron pilot, F/O František Vindiš, shared in shooting down another Fw 190.[1]

V1 flying bombs

On 13 June 1944 the first German V-1 flying bomb had hit London. Allied countermeasures included training fighter pilots to intercept them. In one sortie on 8 July Smik brought down three V-1 bombs in 32 minutes.[1]

Promotion and more friction

On 11 July 1944 Smik was promoted to Flight Lieutenant and posted to 312 Squadron to command its "B" flight. But here some pilots still resented him, feeling that they should have been promoted to that position. But the squadron's senior officers recognised Smik's achievements and suitability for the job, and resentment of him was quashed.[1]

At this stage 312 Squadron was flying Spitfire Mk IX aircraft, with which it escorted RAF Bomber Command and United States Army Air Forces heavy bombers that attacked targets in the German-occupied Netherlands. But by now Luftwaffe resistance was limited.[1]

Accordingly, 312 Squadron's rôle shifted to attacking targets on the ground. As with 222 Squadron in 1943, Smik again proved to be an aggressive pilot who seldom missed an opportunity to attack. Railway locomotives were a favourite target.[1]

In one raid in August, Smik and his flight of four Spitfires went to attack an airfield at Steenwijk in Overijssel but found no Luftwaffe aircraft to attack. On the way to Steenwijk they had seen three railway trains in a rail yard at Raalte, so on the way back Smik and his flight attacked it. One of the trains was loaded with 15 to 20 tanks, all of which they destroyed.[1]

First crash in the Netherlands

On 3 September 1944 Smik took part in the escort of Ramrod 1258, which was bomber raid on Soesterberg Air Base in Utrecht Province. On the way back Smik saw about 30 Junkers Ju 188 medium bombers on the ground at Gilze-Rijen Air Base in North Brabant. Smik led his flight of four Spitfires to attack, but the airfield's ground defences retaliated with intense and accurate anti-aircraft fire. Smik hit two Ju 188s and set them on fire, but his Spitfire was badly hit and he had to make a forced landing near the village of Prinsenbeek.[1]

The village was in German-held territory, but villagers successfully hid him. Then Dutch resistance members hid him first in Breda and then in the village of Ginneken, where he was joined other RAF and USAAF airmen who were evading capture. On 26 October they escaped through the German front line, where they came under machine gun fire and managed to cross a minefield to reach the Allied front line.[1]

Squadron leader and death

In November 1944 Smik was promoted to Squadron Leader and given command of No. 127 Squadron RAF, which was then operating Spitfire LF Mark IXe and Mark XVIe aircraft. The squadron was based at Grimbergen Airfield in Belgium and helping Allied ground forces such as the First Canadian Army to liberate the Netherlands.[1]

On the morning of 28 November Smik led a reconnaissance patrol over Arnhem, Hengelo and then Zwolle, where he led an attack on a railway marshalling yard. Heavy German anti-aircraft fire shot down two Spitfires, killing both pilots. One was RR229, flown a Free Belgian pilot, F/O Henri Taymans, which crashed near Kampen. The other was RR227 flown by Smik, which crashed near Ittersum, which is now part of Zwolle.

Taymans' Spitfire crashed into a dyke next to a railway embankment and was not found for 20 years. Smik's aircraft was found and his body recovered, but not identified.[1] Smik was carrying no identification. Many Czechoslovaks serving in Allied armed forces took precautions to prevent being identified if they were killed behind enemy lines or captured, as otherwise the Germans carried out reprisals against their families in occupied Czechoslovakia.

Burial, exhumations and reburials

Smik was buried at Kranenburg near Bronckhorst in Gelderland as an "unknown Englishman". After the Netherlands were liberated, his body was wrongly identified as Taymans'. The Belgian pilot had a fiancée, who had the body exhumed and reinterred in a family burial vault in Brussels.[1]

On 12 May 1965 workmen digging in the dyke at Kampen found Spitfire RR229 and the remains of Henri Taymans' body. As a result, Smik's body was removed from the vault in Brussels and reburied, this time at Adegem Canadian War Cemetery near Ghent in East Flanders.[1]

In 1992–93 Czechoslovakia was dissolved. In 1994 the government of Slovakia had Smik's body exhumed again and on 12 September he was reinterred in Slávičie Údolie cemetery in Bratislava.[1]

Achievements and honours

Smik flew more than 371 flying hours in 263 sorties. His victories included eight enemy aircraft shot down single-handed, two more shared, two more probables, and four damaged. In one sortie he shot down three V-1 flying bombs in 32 minutes. From the air he also destroyed numerous targets on the ground, including two Ju 188 bombers, two tanks, 22 other military vehicles and six railway locomotives.[1]

Smik was the RAF's highest-scoring Czechoslovak ace in 1943 and again in 1944: a period when Luftwaffe presented far fewer airborne targets than it had earlier in the war. He was the RAF's fifth-highest scoring Czechoslovak ace and highest-scoring Slovak ace in the Second World War.[1]

Monuments and memorials

In 1994 Slovenská televízia broadcast a documentary Stratený syn Slovenska ("Lost Son of Slovakia") about Smik. On 19 July 1995 the Slovak Air Force posthumously promoted Smik to Major-General. In 2006 the British Ambassador in Bratislava presented a replica of Smik's DFC to the Slovak Air Force headquarters at Zvolen in central Slovakia.[1]

On 28 August 2002 Sliač airbase was renamed his in honour. On 1 July 2009 a wing of the Slovak Air Force based at Sliač was renamed the Zmiešane Krídlo Generála Otta Smika, Sliač ("Combined Wing of General Otto Smik, Sliač").[1] It is now called the Taktické krídlo generálmajora Otta Smika Sliač ("Tactical Wing of Major General Otto Smik Sliač").[2] On 26 October 2010 a bust of Smik was unveiled at the headquarters of the "Combined Wing of General Otto Smik, Sliač".[1][3] There is an annual air show at Sliač. Since 2012 it has included a "Best display Smik Trophy".

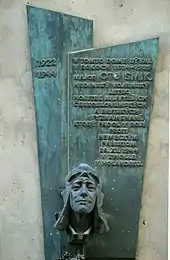

In Bratislava there is a bronze plaque commemorating Smik designed by the sculptor Milan Struhárik. In March 1992 a plaque was unveiled at the farm at Blooksteed in the Netherlands where Smik crashed and died.[1]

Three streets are named after Smik: "Otto Smikstraat" in Zwolle, "Smikova" in the Černý Most suburb of Prague[1] and "Smikova" in Bratislava.

Awards

Distinguished Flying Cross

Distinguished Flying Cross 1939–1945 Star

1939–1945 Star Air Crew Europe Star

Air Crew Europe Star Defence Medal

Defence Medal War Medal 1939–1945

War Medal 1939–1945_-_ribbon_bar.png.webp) Croix de guerre with palm leaf (France)

Croix de guerre with palm leaf (France)_Bar.png.webp) Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945 five times

Czechoslovak War Cross 1939–1945 five times Československá medaile Za chrabrost před nepřítelem ("Bravery in Face of the Enemy")

Československá medaile Za chrabrost před nepřítelem ("Bravery in Face of the Enemy")_BAR.svg.png.webp) Pamětní medaile československé armády v zahraničí ("Commemorative Medal of the Czechoslovak Army Abroad") with France and Great Britain bars

Pamětní medaile československé armády v zahraničí ("Commemorative Medal of the Czechoslovak Army Abroad") with France and Great Britain bars

References

Notes

- "Otto Smik". Free Czechoslovak Air Force. 19 August 2010. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- "Taktické krídlo generálmajora Otta Smika Sliač" (in Slovak). Ministerstvo obrany Slovenskej republiky. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

- Suja, Milan (26 November 2010). "Najlepší slovenský pilot má bustu v Sliači" (in Slovak). MY náš Zvolen. Retrieved 7 November 2017.

Bibliography

- Brown, Alan (2000). Airmen in Exile, The Allied Air Forces in WWII. Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-2012-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Otto Smik. |

- Habšudová, Zuzana (4 February 2002). "Slovak Otto Smik – Youngest hero of the English skies". The Slovak Spectator. The Rock, s.r.o.

- Rak, Michal (30 June 2003). "Otto Smik" (in Czech). Valka.

- "Otto Smik" (in Slovak). Osobnosti.

- "Spitfire over Prague". Free Czechoslovak Air Force. 30 November 2014.