Palestinian enclaves

The Palestinian enclaves, also figuratively described as the Palestine Archipelago,[lower-alpha 1][1][2][3] are proposed areas in the West Bank designated for Palestinians under a variety of US and Israeli-led proposals to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[lower-alpha 2][4] By way of the popular comparison between Israel and apartheid-era South Africa, the enclaves are also referred to as the West Bank bantustans.[lower-alpha 3]

.jpg.webp)

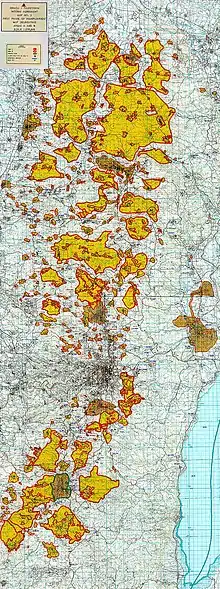

The "islands" first took official form as Areas A and B under the 1995 Oslo II Accord; this arrangement was explicitly intended to be temporary with Area C (the rest of the West Bank) to "be gradually transferred to Palestinian jurisdiction" by 1997; no such transfers were made.[7][8][lower-alpha 4] The area of the West Bank currently under partial civil control of the Palestinian National Authority is composed of 165 "islands".[lower-alpha 5] The creation of this arrangement has been called "the most outstanding geopolitical occurrence of the past quarter century."[lower-alpha 6]

A number of Israeli-US peace plans, including the Allon Plan, the Drobles World Zionist Organization plan, Menachem Begin's plan, Benjamin Netanyahu's "Allon Plus" plan, the 2000 Camp David Summit, and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state have proposed a bantustan/enclave-type territory – i.e. a group of non-contiguous areas surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel;[lower-alpha 7][lower-alpha 8] as has the more recent Trump peace plan.[9][10] This has been referred to as the Bantustan option.[lower-alpha 9][lower-alpha 10][lower-alpha 11]

The impact of the creation of these fragmented Palestinian areas has been studied widely, and has been shown to have had a "devastating impact on the economy, social networks, the provision of basic services such as healthcare and education".[lower-alpha 12]

Names

A variety of terms are used by Palestinians and outside observers to describe these spaces, including "enclaves,"[lower-alpha 13] "cantons,"[lower-alpha 14] and "open-air prisons"[lower-alpha 15] while "islands" or "archipelago" is considered to communicate how the infrastructure of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank has disrupted contiguity between Palestinian areas.[11] "Swiss cheese" is another popular analogy.[12][13] Of these terms, 'enclaves', 'cantons'[14] and archipelago[lower-alpha 16] have also been applied to the pattern of Jewish settlements in the West Bank.

The entities are often referred to as bantustans, typically by critics; the term bantustan comes from the enclaves in Apartheid South Africa set aside for black inhabitants. However, usage of the term "bantustans" to describe the areas has also been traced back to the 1960s including by Israeli military leader and politician Moshe Dayan, who reportedly suggested bantustans as an explicit model for the Palestinian enclaves. The name "bantustan" is considered to have economic and political implications that imply a lack of meaningful sovereignty[lower-alpha 17] and is used pejoratively.[15] A number of Israelis and Americans have used the word to describe the enclaves including Moshe Dayan,[lower-alpha 18] Ariel Sharon,[lower-alpha 19] Colin Powell,[16] Martin Indyk,[lower-alpha 20] Daniel Levy,[17] Amos Elon,[17] Gershom Gorenberg,[18] I. F. Stone,[lower-alpha 21] Avi Primor,[lower-alpha 22] Ze'ev Schiff,[19] Meron Benvenisti,[lower-alpha 23] Yuval Shany[20] and Akiva Eldar.[lower-alpha 24]

The process of creating the fragmented enclaves has been described as "encystation" by Professor Glenn Bowman, Emeritus Professor of Politics and International Relations at Kent University,[21] and as "enclavization" by Professor Ghazi Falah at the University of Akron.[22][23] The verbal noun "bantustanization" was first used by Azmi Bishara in 1995, though Yassir Arafat had made the analogy earlier in peace talks to his interlocutors.[24] "Researchers and writers from the Israeli left"[25] began using it in the early 2000s, with Meron Benvenisti referring in 2004 to the territorial, political and economic fragmentation model being pursued by the Israeli government.[26]

Israeli planning in the West Bank before Oslo

After the 1967 Six-Day War, a small group of officers and senior Israeli officials advocated that Israel unilaterally plan for a Palestinian mini-state or "canton", in the north of the West Bank.[lower-alpha 25] Policymakers did not implement this cantonal plan at the time. Defense minister Moshe Dayan said that Israel should keep the West Bank and Gaza Strip, arguing that a "sort of Arab "bantustan" should be created with control of internal affairs, leaving Israel with defence, security and foreign affairs".[lower-alpha 18] Just weeks after the war, the noted American Jewish intellectual I. F. Stone wrote in a widely read article that "it would be better to give the West Bank back to Jordan than to try to create a puppet state — a kind of Arab Bantustan".[lower-alpha 21]

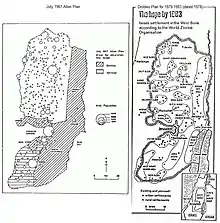

Allon plan

In early 1968, Yigal Allon, the Israeli minister after whom the 1967 Allon Plan is named, proposed reformulating his plan by transferring some Palestinian areas back to Jordan. In his view, not to give back to that country Palestinian land outside of the territory proposed for annexation for Israeli settlement would leave Palestinians with an autonomy under Israeli rule, a situation that would lead observers to conclude that Israel had set up an arrangement akin to "some kind of South African Bantustan".[lower-alpha 26] According to the plan, Israel would annex most of the Jordan Valley, from the river to the eastern slopes of the West Bank hill ridge, East Jerusalem, and the Etzion bloc while the heavily populated areas of the West Bank hill country, together with a corridor that included Jericho, would be offered to Jordan.[27] Allon's intention was to create a zone deemed necessary for security reasons between Israel and Jordan and set up an "eastern column" of agricultural settlements.[28] The plan would have annexed about 35 percent of the West Bank with few Palestinians.[29]

1968 Jerusalem plan

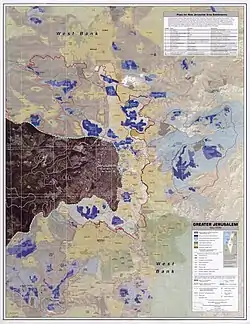

On 27 June 1967, Israel expanded the municipal boundaries of West Jerusalem so as to include approximately 70 km2 (27.0 sq mi) of West Bank territory today referred to as East Jerusalem, which included Jordanian East Jerusalem (6 km2 (2.3 sq mi)) and 28 villages and areas of the Bethlehem and Beit Jala municipalities (64 km2 (25 sq mi)).[30][31][32]

The masterplan defined the need to ensure "unification of Jerusalem" and prevent a later division. Pursuant to this and subsequent plans, twelve Israeli settlements were established in such a way as to "complete a belt of built fabric that enveloped and bisected the Palestinian neighborhoods and villages annexed to the city."[30] The plan called for Jewish neighborhood construction in stages beginning shortly after the war with Ramot Eshkol, French Hill and Givat HaMivtar "closing the gap in the north of the city." Then in the 1970s through early 1980s, in the four comers of the annexed areas, Ramot and Neve Ya'akov in the north and Gilo and East Talpiot in the south. The third stage included Pisgat Ze'ev in 1980 and "the creation of an outer security belt", Ma'ale Adumim (1977), Givon (1981) and Efrat (1983) on high ground and beside strategic roads in the Palestinian area. Har Homa (1991) and attempts to achieve a link between this neighborhood and Ma'ale Adumim, known as the "Greater Jerusalem" plan.[33]

Drobles and Sharon plans

Ariel Sharon was the primary figure behind Likud's policy for Israeli settlements in the Palestinian territories for decades, and is widely regarded as their main architect.[35][36][37] According to Ron Nachman, Sharon had been thinking about the issue of settlement in the conquered territories since 1973, and his map of settlement, outlined in 1978, had not essentially changed by the time he implemented the Separation Barrier.[38]

In September 1977, in the first Likud government, Ariel Sharon took over the Ministerial Committee for Settlement and announced the first in a series of plans for new settlements[lower-alpha 27] to be organized in a web of blocks of settlements of different sizes situated on the mountain ridges across the full depth of the West Bank in and around Palestinian cities and villages. Sharon thought the Allon plan insufficient unless the high terrain was also fortified.[39]

Later, Sharon's plans were adopted as the Masterplan for the Development of Settlement in Judea and Samaria for the Years 1979–1983, Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization, Jerusalem, 1979, authored by Matityahu Drobles(s).[40] In 1982, Sharon, then Minister of Defence, published his master plan for Jewish Settlements in the West Bank Through the Year 2010 which became known as the Sharon Plan.[41]

Plans including the Allon, Drobles and Sharon master plans as well as the Hundred Thousand plan, never officially acknowledged, were the blueprint for West Bank settlements.[42] According to professor Saeed Rahnema, these plans envisaged "the establishment of settlements on the hilltops surrounding Palestinian towns and villages and the creation of as many Palestinian enclaves as possible." while many aspects formed the basis of all the failed "peace plans" that ensued.[43]

The Road to Oslo

According to the former deputy director-general of the Israeli Foreign Ministry's department for Africa, Asia and Oceania, then ambassador and vice president of Tel Aviv University Avi Primor, writing in 2002, in the top echelons of the Israeli security establishment in the 1970s and 1980s there was widespread empathy for South Africa's apartheid system and were particularly interested in that country's resolution of the demographic issue by inventing bantustan "homelands" for various groups of the indigenous black population.[lower-alpha 22] Pro-Palestinian circles and scholars, despite the secrecy of the tacit alliance between Israel and South Africa, were familiar with ongoing arrangements between the two in military and nuclear matters, though the thriving cooperation between Israel and the Bantustans themselves was a subject that remained neglected until recently, when South Africa's archives began to be opened up.[44]

Autonomy

By the early 1970s, Arabic-language magazines began to compare the Israeli proposals for a Palestinian autonomy to the Bantustan strategy of South Africa,[45] In January 1978, PLO leader Yasser Arafat criticized a peace offering from Menachem Begin as "less than Bantustans".[lower-alpha 28] The September 1978 Camp David accords included provision for the Palestinians, who did not participate, based on Begin's 1977 Plan for West Bank and Gaza Strip.[46] (The New York Times 1977)

Hundred Thousand plan

Published in 1983, the "Ministry of Agriculture and the Settlement Division of the World Zionist Organization, Master Plan for Settlement for Judea and Samaria, Development Plan for the Region for 1983-1986" aimed at building settlements through 2010 by attracting 80,000 Israelis to live in 43 new Israeli settlements in order to raise the total settler population to 100,000 and for whom up to 450 km of new roads are to be paved (UNHCR 2013, p. 31).

In late 1984 some embarrassment was caused when the Israeli settlement of Ariel in the West Bank paired itself as a sister city with Bisho, the "capital" of the ostensibly independent Bantustan of Ciskei.[lower-alpha 29] Shortly afterwards, Shimon Peres the new Prime Minister of a Labour-Likud national coalition government, condemned apartheid as an "idiotic system".[47] In 1985, the National Conference of Black Lawyers in the United States compiled a report, entitled Bantustans in the Holy Land, making the analogy with what was taking place in the West Bank. The term was much maligned at that time, but 15 years later an Ameican comparative law scholar and Africanist, Adrien Wing wrote that events in the ensuing decade and a half regarding the way territory was being regulated seemed to support the cogency of the analogy.[48]

Seven Stars plan

Sharon announced this plan in 1991, calling for settlements on the Green Line, with the "declared intention of its consequent eradication."[49]

Meretz plan

The Meretz-Sheves 1992 plan contemplated four Palestinian cantons divided by zones of Jewish settlement and later evolved as a plan to annex all major settlement blocs along with three "autonomous Palestinian enclaves" described as the "Bantustanization" of a "self determination unit".[50]

Oslo Accords

Soon after the joint signing of the Oslo I Accord on 13 September 1993, Yassir Arafat and Simon Peres engaged in follow-up negotiations at the Unesco summit held in December that year in Granada. Arafat was incensed at what he saw as the impossible terms rigidly set by Peres regarding Israeli control of border exits with Jordan, stating that what he was being asked to sign off on resembled a bantustan.[lower-alpha 30] This, Peres insisted, was what had been agreed to at Oslo. Subsequently, on 4 May 1994, Israel and the PLO signed the Gaza–Jericho Agreement that stipulated arrangements for the withdrawal of Israeli troops from both named areas. Azmi Bishara commented that the model envisaged for Gaza was a Bantustan, one even more restrictive in its implications and scope than the ones existing in South Africa. This in turn was taken to signal that the same model would be applied in the future to the West Bank, as with Jericho.[51]

The 1995 Oslo II Accord formalized the fragmentation of the West Bank, allotting to the Palestinians over 60 disconnected islands;[lower-alpha 31] by the end of 1999 the West Bank had been divided into 227 separate entities, most of which were no more than 2 square kilometres (0.77 sq mi) (about half the size of New York's Central Park).[lower-alpha 32] These areas, composing what is known as Area A (c.1005km2; 17.7% of the West Bank) and Area B (c.1035km2; 18.3% of the West Bank), formalized the legal limitation to urban expansion of Palestinian populated areas outside of these fragments.[52] These arrangements were, however, agreed at Oslo to be temporary, with the rest of the West Bank to "be gradually transferred to Palestinian jurisdiction" by 1997; no such transfers were made.[7]

The Oslo map has been referred to as the Swiss Cheese map.[12][53] The Palestinian negotiators at Oslo were not shown the Israeli map until 24 hours before the agreement was due to be signed,[12] and had no access to maps of their own in order to confirm what they were being shown.[54] Yasser Arafat was quoted by Uri Savir, the Israeli chief negotiator at Oslo, as follows: "Arafat glared at [the map] in silence, then sprang out of his chair and declared it to be an insufferable humiliation. "These are cantons! You want me to accept cantons! You want to destroy me!""[12]

Professor Shari Motro, then an Israeli secretary in the Oslo delegation, described in 2005 part of the story behind the maps:

Some people claim that the Oslo process was deliberately designed to segregate Palestinians into isolated enclaves so that Israel could continue to occupy the West Bank without the burden of policing its people. If so, perhaps the map inadvertently revealed what the Israeli wordsmiths worked so diligently to hide. Or perhaps Israel's negotiators purposefully emphasized the discontinuity of Palestinian areas to appease opposition from the Israeli right, knowing full well that Arafat would fly into a rage. Neither is true. I know, because I had a hand in producing the official Oslo II map, and I had no idea what I was doing. Late one night during the negotiations, my commander took me from the hotel where the talks were taking place to an army base, where he led me to a room with large fluorescent light tables and piles of maps everywhere. He handed me some dried-out markers, unfurled a map I had never seen before, and directed me to trace certain lines and shapes. Just make them clearer, he said. No cartographer was present, no graphic designer weighed in on my choices, and, when I was through, no Gilad Sher reviewed my work. No one knew it mattered.[55][53]

Motro's then superior officer, Shaul Arieli, who drew and was ultimately responsible for the Oslo maps, explained that the Palestinian enclaves were created by a process of subtraction, consigning the Palestinians to those areas that the Israelis considered "unimportant":[56]

The process was very easy. In the agreement signed in '93, all those areas that would be part of final status agreement—settlements, Jerusalem, etc.—were known. So I took out those areas, along with those roads and infrastructure that were important to Israel in the interim period. It was a new experience for me. I did not have experience of mapmaking before. I of course used many different civilian and military organizations to gather data on the infrastructure, roads, water pipes, etc. I took out what I thought important for Israel.[56]

The islands isolate Palestinian communities from one another, whilst allowing them to be "well guarded" and easily contained by the Israeli military.[57] The arrangements result in "inward growth" of Palestinian localities, rather than urban sprawl.[57] Many observers, including Edward Said, Norman Finkelstein and seasoned Israeli analysts such as Meron Benvenisti were highly critical of the arrangements, with Benvenisti concluding that the Palestinian self-rule sketched out in the agreements was little more than a euphemism for Bantustanization.[58][59] Defenders of the agreements made in the 1990s between Israel and the PLO rebuffed criticisms that the effect produced was similar to that of South Africa's apartheid regime, by noting that, whereas the Bantustan structure was never endorsed internationally, the Oslo peace process's memoranda had been underwritten and supported by an international concert of nations, both in Europe, the Middle East and by the Russian Federation.[60]

Netanyahu and the Wye River Accord

A subsequent Wye River Accord negotiated with Binjamin Netanyahu drew similar criticism. Israeli author Amos Elon wrote in 1996 that the idea of Palestinian independence is "anathema" to Netanyahu, and that "[t]he most he seems ready to grant the Palestinians is a form of very limited local autonomy in some two or three dozen Bantustan-style enclaves".[lower-alpha 33] Noam Chomsky argued that the situation envisaged still differed from the historical South African model in that Israel did not subsidize the fragmented territories it controlled, as South Africa did, leaving that to international aid donors; and secondly, despite exhortations from the business community, it had, at that period, failed to set up maquiladoras or industrial parks to exploit cheap Palestinian labour, as had South Africa with the bantustans.[61] He did draw an analogy however between the two situations by claiming that the peace negotiations had led to a corrupt elite, the Palestinian Authority, playing a role similar to that of the black leadership appointed by South Africa to administer their Bantustans.[60] Chomsky concluded that it was in Israel's interest to agree to call these areas states.[lower-alpha 34]

Subsequent peace plans

Camp David Summit 2000

Talks to achieve a comprehensive resolution of the conflict were renewed at the Camp David Summit in 2000, only to break down. Accounts differ as to which side bore responsibility for the failure. Ehud Barak's offer was widely reported as 'generous' and, according to Dennis Ross, a participant, would have conceded Palestinians 97% of the West Bank. Others contend that despite an undertaking to withdraw from most of their territory, the resulting entity would still have consisted of several bantustans.[62] Israeli journalist Ze'ev Schiff argued that "the prospect of being able to establish a viable state was fading right before [the Palestinians'] eyes. They were confronted with an intolerable set of options: to agree to the spreading occupation... or to set up wretched Bantustans, or to launch an uprising."[19]

Sharon, Olmert and Bush

On his election to the Israeli Prime Ministership in March 2001, Sharon expressed his determination not to allow the Road map for peace advanced by the first administration of George W. Bush to hinder his territorial goals, and stated that Israeli concessions at all prior negotiations were no longer valid. Several prominent Israeli analysts concluded that his plans torpedoed the diplomatic process, with some claiming that his vision of Palestinian enclaves resembled the Bantustan model.[lower-alpha 36]

It emerged that in private Sharon indeed had openly confided, when as Foreign Minister for the Netanyahu government, to a foreign statesman as early as April 1999,[63][64][lower-alpha 37] that he had in mind the Apartheid Bantustan example as furnishing an 'ideal solution to the dilemma of Palestinian statehood'.[65][lower-alpha 19][68] When d'Alema, at a private dinner he hosted for Israelis in Jerusalem in late April 2003, mentioned his recollection of Sharon's Bantustan views, one Israeli countered by suggesting that his recall must be an interpretation, rather than a fact. d'Alema replied that that the words he gave were 'a precise quotation of your prime minister.' Another Israeli guest present at the dinner deeply invpolved in cultivating Israeli-South African relations, confirmed that 'whenever he happened to encounter Sharon, he would be interrogated at length about the history of the protectorates and their structures.'.[69] In the same year Sharon himself was forthcoming in avowing that it informed his plan to construct a "map of a (future) Palestinian state".[lower-alpha 38] Not only was the Gaza Strip to be reduced to a bantustan, but the model there, according to Meron Benvenisti, was to be transposed to the West Bank by ensuring, simultaneously, that the Wall itself broke up into three fragmented entities Jenin-Nablus, Bethlehem-Hebron and Ramallah.[lower-alpha 23][70]

Avi Primor in 2002 described the implications of the plan: "Without anyone taking notice, a process is underway establishing a 'Palestinian state' limited to the Palestinian cities, a 'state' comprisedof a number of separate, sovereign-less enclaves, with no resources for self-sustenance."[71] In 2003, the historian Tony Judt, arguing that the peace process had effectively been killed, leaving 'Palestinian Arabs corralled into shrinking Bantustans.'[lower-alpha 39] Commenting on these plans in 2006, Elisha Efrat, Professor of urban geography at TAU argued that any state created on these fragmented divisions would be neither economically viable nor amenable to administration.[lower-alpha 40]

Sharon eventually disengaged from the Gaza in 2005, and in the ensuing years, during the Sharon-Peres interregnum and the government of Ehud Olmert it became a commonplace to speak of the result there, where Hamas assumed sole authority over the internal administration of the Strip, as the state of Hamastan.[lower-alpha 41][lower-alpha 42] At the same time, according to Akiva Eldar, the Sharon plan to apply the same policy of creating discontinuous enclaves for Palestinians in the West Bank was implemented.[lower-alpha 24] In his Sadat lecture of 14 April 2005, former United States Secretary of State James Baker said that "Finally, the administration must make it unambiguously clear to Israel that while Prime Minister Sharon's planned withdrawal from Gaza is a positive initiative, it cannot be simply the first step in a unilateral process leading to the creation of Palestinian Bantustans in the West Bank".[72] The maps for Sharon's disengagement from Gaza, Camp David and Oslo are similar to each other and to the 1967 Allon plan.[73] By 2005, together with the Separation Wall, that area had been potted with 605 closure barriers whose overall effect was to create a 'matrix of contained quadrants controllable from well-defended, fixed military positions and settlements.[lower-alpha 43][lower-alpha 44] Olmert's Realignment plan (or convergence plan) are terms used to describe a method whereby Israel creates a future Palestinian state of its own design as foreseen by the Allon plan, to minimize the amount of land on which a Palestinian state would exist by fixing facts on the ground to affect future negotiations.[74]

Netanyahu and Obama

In 2016, the last year of his presidency, Barack Obama and John Kerry discussed a number of detailed maps showing the fragmentation of the Palestinian areas. Advisor Ben Rhodes said that "the President was shocked to see how "systematic" the Israelis had been at cutting off Palestinian population centers from one another." These findings were discussed with the Israeli government; the Israelis "never challenged those findings". Obama's realization was reported to be the reason that he abstained on the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334 which condemned the settlements.[75]

According to Haaretz's Chemi Shalev, in a speech marking the 50th anniversary of the Six-Day War, "Netanyahu thus envisages not only that Palestinians in the West Bank will need Israeli permission to enter and exit their "homeland", which was also the case for the Bantustans, but that the IDF will be allowed to continue setting up roadblocks, arresting suspects and invading Palestinian homes, all in the name of "security needs"."[76] In a 2016 interview, former Israeli MK Ksenia Svetlova argued that West Bank disengagement would be very difficult and that a more likely outcome was "annexation and controlling Palestinians in Bantustans".[77]

Trump peace plan

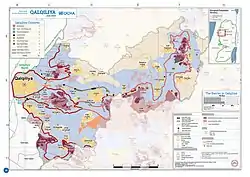

The 2020 Trump peace plan proposed splitting a possible "State of Palestine" into five zones:[78]

- A reduced Gaza Strip connected by a road to two uninhabited districts in the Negev desert;

- Part of the southern West Bank;

- A central area around Ramallah, almost trisected by a number of Israeli settlements;

- A northern area including Nablus, Jenin, and Tulkarm;

- A small zone including Qalqilya, surrounded by Israeli settlements.

Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas commented on the fragmented nature of the proposal at the United Nations Security Council, waving a picture of the fragmented cantons and stating: "This is the state that they will give us. It's like a Swiss cheese, really. Who among you will accept a similar state and similar conditions?"[13] According to Professor Ian Lustick, the appellation "State of Palestine" applied to this archipelago of Palestinian-inhabited districts is not to be taken any more seriously than the international community took apartheid South Africa's description of the bantustans of Transkei, Bophuthatswana, Venda, and Ciskei as "independent nation-states."[78]

When the plan emerged, Yehuda Shaul argued that the proposals were remarkably similar to the details set forth both in the 1979 Drobles Plan, written for the World Zionist Organization and entitled Master Plan for the Development of Settlements in Judea and Samaria, 1979–1983, and key elements of the earlier Allon Plan, aimed at ensuring Jewish settlement in the Palestinian territories, while blocking the possibility that a Palestinian state could ever emerge.[79][lower-alpha 45]

The plan in principle contemplates a future Palestinian state, "shrivelled to a constellation of disconnected enclaves, following Israeli annexation," while a group of UN human rights experts said "What would be left of the West Bank would be a Palestinian Bantustan, islands of disconnected land completely surrounded by Israel and with no territorial connection to the outside world."[9][10] Commenting on the plan, Daniel Levy, former Israeli negotiator and president of the U.S./Middle East Project wrote that "The visuals of the map proposed are a dead giveaway: a patchwork of Palestinian islands best viewed alongside the map of South Africa's apartheid-era Bantustans."[17] The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territory Michael Lynk commented that Trump's proposal was not a recipe for peace as much as an endorsement of "the creation of a 21st century Bantustan in the Middle East."[lower-alpha 46]

Netanyahu annexation plan

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced on 6 April 2019, three days before the Israeli elections, that he would not give up any settlement and would extend gradually Israeli sovereignty to Judea and Samaria.[20] Al Jazeera reported the following year that Netanyahu was expected on 1 July 2020 to announce Israel's annexation of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea. Citing calculations by Peace Now, this most recent proposal would seize around 1,236 square kilometres (477 sq mi) of land from the Jordan Valley compared to the 964 square kilometres (372 sq mi) of Trump's conceptual map.[80] In the event, the proposal was not implemented.[81]

According to Yuval Shany, Hersch Lauterpacht Chair in International Law at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Netanyahu's annexation plans violated the Oslo Accords, and the two-state solution Netanyahu had formerly accepted. The effective result of such plans would be to "effectively create(s) Palestinian enclaves in the nonannexed area with limited contiguity and almost certainly no sustainable viability as an independent state. This division of territorial control looks more like the South African system of Bantustans than the foundation of a viable two-state solution."[20] 50 UN experts went public stating that the result would be Bantustans, with Jewish South African-Israeli writer Benjamin Pogrund, formerly opposed to the Apartheid analogy also claiming that the proposal would effectively introduce an apartheid system.[82]

Key issues

Settlements

The Allon Plan, the Drobles World Zionist Organization plan, Menachem Begin's plan, Benjamin Netanyahu's "Allon Plus" plan, the 2000 Camp David Summit, and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state all foresaw a territory surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel,[lower-alpha 7][lower-alpha 8] as did the more recent Trump peace plan.[9][10]

Land expropriation

In 2003, Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food Jean Ziegler reported that he:

is also particularly concerned by the pattern of land confiscation, which many Israeli and Palestinian intellectuals and non-governmental organizations have suggested is inspired by an underlying strategy of "Bantustanization". The building of the security fence/apartheid wall is seen by many as a concrete manifestation of this Bantustanization as, by cutting the OPT into five barely contiguous territorial units deprived of international borders, it threatens the potential of any future viable Palestinian State with a functioning economy to be able to realize the right to food of its own people.[83]

The Financial Times published a 2007 U.N. map and explained: "The UN mapmakers focused on land set aside for Jewish settlements, roads reserved for settler access, the West Bank separation barrier, closed military areas and nature reserves," and "What remains is an area of habitation remarkably close to territory set aside for the Palestinian population in Israeli security proposals dating back to postwar 1967."[84]

In a 2013 report on the Palestinian economy in East Jerusalem, UNCTAD's conclusions noted increased demolitions of Palestinian property and homes as well as settlement growth in the areas surrounding East Jerusalem and Bethlehem adding "to the existing physical fragmentation between different Palestinian "bantustans" – drawing on South African experience of economically dependent, self-governed "homelands" existing within the orbit of the advanced metropolis,.."[85] A 2015 report of the Norwegian Refugee Council noted the impact of Israeli policies in key areas of East Jerusalem, principally the Wall and settlement activity, particularly in regard to Givat HaMatos and Har Homa.[lower-alpha 47]

According to Haaretz, in November 2020, the Israeli Transportation Ministry announced a highway and transportation master plan through 2045, the first of its kind for the West Bank. Details about the plans are contained in a new report Highway to Annexation which concludes "West Bank road and transportation development creates facts on the ground that constitute a significant entrenchment of the de facto annexation already taking place in the West Bank and will enable massive settlement growth in the years to come."[86][87]

Contiguity

In 2004, Colin Powell was asked what George W. Bush meant when he spoke of a "contiguous Palestine"; Powell explained that "[Bush] was making the point that you can't have a bunch of little Bantustans or the whole West Bank chopped up into noncoherent, noncontiguous pieces, and say this is an acceptable state."[16] Rather than territorial contiguity, Sharon had in mind transportation contiguity.[88] In 2004 Israel asked international donors to fund a new road network for Palestinians, that would run under and over the existing settler-only network. Since acceptance would have implied official approval of the settlement enterprise, the World Bank refused.[89][90][91] While Israelis could traverse the contiguous Area C, settler-only roads divided the West Bank into a series of non-contiguous areas for Palestinians wanting to reach Areas A and B.[92] In 2007, Special Rapporteur John Dugard wrote[93]

The number of checkpoints, including roadblocks, earth mounds and trenches, increased from 376 in August 2005 to 540 in December 2006. These checkpoints divide the West Bank into four distinct areas: the north (Nablus, Jenin and Tulkarem), the centre (Ramallah), the south (Hebron) and East Jerusalem. Within these areas further enclaves have been created by a system of checkpoints and roadblocks. Moreover highways for the use of Israelis only further fragment the Occupied Palestinian Territory into 10 small cantons or Bantustans.

The arrangements have fragmented the Palestinian communities into "weak and impoverished sub-communities, where centers are disconnected from peripheries, urban centers are eroding and rural areas becoming poor, families are separated, and medical treatment is denied along with access to higher education."[94] Meron Benvenisti wrote in 2006 that the Israeli government hopes that this will result in "demographic distress and perhaps to emigration", but that "Palestinian society is demonstrating signs of strong cohesion and adjustment to the cruel living conditions forced on it, and there are no signs that the strategic goals have in fact been achieved."[94]

Criticism of non-contiguity has continued in subsequent years. In 2008, the last year of his presidency, Bush stated "Swiss cheese isn't going to work when it comes to the outline of a state. To be viable, a future Palestinian state must have contiguous territory."[95] In 2020, former US Ambassador to Israel, Martin Indyk, noted that the Trump Plan proposed transportational contiguity instead of territorial contiguity, via "tunnels that would connect the islands of Palestinian sovereignty. Those tunnels, of course, would be under Israeli control."[lower-alpha 20]

Significance

The creation of the bantustans has been called "the most outstanding geopolitical occurrence of the past quarter century."[lower-alpha 6]

Notes

- "In 2009, French artist Julien Bousac designed a map of the West Bank titled "L'archipel de Palestine orientale, " or "The Archipelago of Eastern Palestine"... Bousac's map illustrates — via a military and a tourist imaginary — how the US-brokered Oslo Accords fragmented the West Bank into enclaves separated by checkpoints and settlements that maintain Israeli control over the West Bank and circumscribe the majority of the Palestinian population to shrinking Palestinian city and village centers." (Kelly 2016, pp. 723–745)

- "Faced with widely drawn international parallels between the West Bank and the Bantustans of apartheid South Africa, senior figures in Mr Netanyahu's Likud party have begun to admit the danger.' (Stephens 2013)

- Also contracted as "Palutustans".'The experience of the past four decades puts a question mark over this assumption. If a Palestinian state is not established, Israel will most likely continue to administer the area, possibly allotting crumbs of sovereignty to Palestinian groups in areas that will continue to function as "Palutustans" (Palestinian Bantustans)."[5] Francis Boyle, former Amnesty International USA board member and legal advisor to the Palestinians in Madrid (1991-1993), and presently professor of International Law at the University of Illinois College of Law, after describing the process of peace negotiations as designed to create a Bantustan for Palestinians, argued that historically, it was Western imperial colonial powers, whose policies in his view had been racist and genocidal that, in creating Israel, had effectively established what was a Bantustan for the Jewish people themselves, an entity he called "Jewistan".[6]

- "In the West Bank Israel has managed to turn the governorates there into Bantustans only connected through an Israeli controlled (Area C) territory." (ITAN 2015, p. 889)

- "90 percent of the population of the West Bank was divided into 165 islands of ostensible PA control." (Thrall 2017, p. 144)

- "The reality of the Palestinian Bantustans, reservations or enclaves — is a fact on the ground. Their creation is the most outstanding geopolitical occurrence of the past quarter century." (Hass 2018)

- "Israel responded to the second intifada with a strategy of collective punishment aimed at a return to the logic of Oslo, whereby a weak Palestinian leadership would acquiesce to Israeli demands and a brutalized population would be compelled to accept a "state" made up of a series of Bantustans. Though the language may have changed slightly, the same structure that has characterized past plans remains. The Allon plan, the WZO plan, the Begin plan, Netanyahu's "Allon Plus" plan, Barak's "generous offer," and Sharon's vision of a Palestinian state all foresaw Israeli control of significant West Bank territory, a Palestinian existence on minimal territory surrounded, divided, and, ultimately, controlled by Israel, and a Palestinian or Arab entity that would assume responsibility for internal policing and civil matters." (Cook & Hanieh 2006, pp. 346–347)

- The 1968 Allon Plan called for placing settlements in sparsely populated lands of the Jordan River Valley, thus ensuring Jewish demographic presence in the farthest location within biblical Israel. This was later complemented by the 1978 Drobles Plan, named after its author Matityahu Drobles, which called for a "belt of settlements in strategic locations … throughout the whole land of Israel … for security and by right." The logic of the Drobles Plan actually guided the wave of settlements that occurred in the 1990s, thus turning the settlements into an integral element of Israel's tactical control over and surveillance of Palestinians in the West Bank. The Allon and Drobles Plans and other similar colonization campaigns have invariably been motivated by five broad, interrelated reasons driving the settlement enterprise. They include control over economic resources, use of territory as a strategic asset, ensuring demographic presence and geographic control, reasserting control over the Jew's biblically promised homeland, and having exclusive rights to the territory (Kamrava 2016, pp. 79–80).

- "Therefore, the Bantustan option of minimizing effective Palestinian statehood to dispersed smaller parts of the West Bank and Gaza, and reversing the Oslo Accord, appeals to influential Israeli planners" (Adam & Moodley 2005, p. 104)

- "This says that through Oslo and recognition Israel has succeeded in replacing one form of occupation with another - the bantustan option." (Usher 1999, p. 35)

- "…much of the American political establishment, the Israeli establishment and the Palestinian establishment (who are mainly affiliated with the Palestinian Authority) are working to produce the Bantustan option - a series of non-contiguous Palestinian cantons in the West Bank governed by a corrupt elite subset of society. It is very likely that before the one-state solution is fully developed, the Bantustan option will be established in the West Bank." (Loewenstein & Moor 2013, p. 14)

- The consequences of the spatial regime being consolidated in the occupied West Bank today, a result of the Israeli policy variously characterized as Bantustanization, cantonization, enclavization, and ghettoization, have been discussed at length in recent years. A tremendous outpouring of documentation and reporting, analysis, opinion, and activism has been devoted to this issue; monitoring by international, Palestinian, and Israeli agencies and organizations has shown the policy of fragmentation's devastating impact on the economy, social networks, the provision of basic services such as healthcare and education, and the prospects for an end to Israel's colonization of the West Bank and Gaza (Taraki 2008, p. 6).

- "The term enclave can seem neutral, unlike Bantustan and ghetto, which are freighted with negative connotations. Yet enclaves are socio-spatial formations that similarly arrange inequality. Gulag captures the arbitrariness of some of closure's mechanisms; but economic factors limit comparisons with the ghetto. The economic integrations, however unequal, of Jews in pre-WWII European ghettos, of blacks in the ghettos of the United States, and of the Bantustans in South Africa, is not paralleled in Palestinian enclaves, where circulation outside and between their confines is severely circumscribed." (Peteet 2017, p. 62)

- 'the original South African model is particularly tempting. It would be a mistake to use the term "canton" in this case, since cantons are autonomous areas of a state and its citizens. Here, the idea is to turn those Palestinians living in areas that would be annexed to Israel, into foreign citizens.'(Primor 2002)

- "The terms 'enclaves', 'cantons', 'Bantustans' and 'open-air prisons' are used by Palestinians and outside observers to describe these spaces...The enclaves contain a population expelled but still within the territory of the state; they are neither camps, detention centers, nor Bantustans. Although certainly lodged in the same analytical field of other spatial devices of containment, they are unique spatial formations that we have yet to develop tools to conceptualize." (Peteet 2016, p. 268)

- 'The dominant security modality in the Occupied Palestinian Territories (OPT) nowadays is the coexistence of an archipelago and enclaves. In the archipelago, people and goods move relatively freely and smoothly. The enclaves, however, are spaces of exception where the rule of law and the emergency procedure merge into indistinction.' (Ghandour-Demiri 2016)

- Ariel Sharon, Israel's Prime Minister since 2001, had long contended that the Bantustan model, so central to the apartheid system, is the most appropriate to the present Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Others, by contrast, have maintained that the Palestinian territories have been transformed into cantons whose final status is still to be determined. The difference in terminology between cantons and Bantustans is not arbitrary though. The former suggests a neutral territorial concept whose political implications and contours are left to be determined. The latter indicates a structural development with economic and political implications that put in jeopardy the prospects for any meaningfully sovereign viable Palestinian state. It makes the prospects for a binational state seem inevitable, if most threatening to the notion of ethnic nationalism.' (Farsakh 2005, p. 231)

- General Dayan has said that a sort of Arab "Bantustan" should be created with control of internal affairs, leaving Israel with defence, security and foreign affairs. Mr. Ben-Gurion has boldly recommended a large-scale Jewish settlement in Hebron (Brogan 1967).

- 'Just as in the Palestinian territories, blacks and colored people in South Africa were given limited autonomy in the country's least fertile areas. Those who remained outside these isolated enclaves, which were disconnected from each other, received the status of foreign workers, without civil rights. A few years ago, Italian Foreign Minister Massimo D'Alema told Israeli friends that shortly before he was elected prime minister, Sharon told him that the bantustan plan was the most suitable solution to our conflict.';[65][66] 'Sharon's conception of a Palestinian 'state' is in fact very akin to the sub-sovereign Bantustan model of apartheid South Africa, a comparison which he is reported to make in private.'[67]

- "The Trump plan would thereby surround the Palestinian state with Israeli territory, severing its contiguity with Jordan and turning Jericho into a Palestinian enclave and the Palestinian state into a Bantustan... The result would be a Swiss cheese Palestinian state with no possibility of territorial contiguity. Instead, the Trump plan proposes 'transportational' contiguity, through tunnels that would connect the islands of Palestinian sovereignty. Those tunnels, of course, would be under Israeli control." (Indyk 2020)

- "...it would be better to give the West Bank back to Jordan than to try to create a puppet state — a kind of Arab Bantustan — consigning the Arabs to second-class status under Israel's control. This would only foster Arab resentment. To avoid giving the Arabs first-class citizenship by putting them in the reservation of a second-class state is too transparently clever." (Stone 1967)

- "Many in the top echelons of the security establishment in the 1970s and 1980s had a warm spot in their hearts for the white apartheid regime in South Africa that was derived not only from utilitarian interests, but also from sympathy for the white minority rulers in that country. One of the elements of the old South African regime that stirred much interest in Israel remains current to this day: To seemingly solve the demographic problem that troubled the white South Africans (that is, to hang on to all of South Africa without granting equal rights, civil rights and the vote to blacks), the South African regime created a fiction known by the name Bantustans, later changed to Homelands." (Primor 2002)

- "with breathtaking daring, Sharon submits a plan that appears to promise the existence of a "Jewish democratic state" via "separation", "the end of the conquest", the "dismantling of settlements" – and also the imprisonment of some 3 million Palestinians in bantustans. This is an "interim plan" that is meant to last forever. The plan will last, however, only as long as the illusion is sustained that "separation" is a means to end the conflict.' (Benvenisti 2004)

- 'Alongside the severance of Gaza from the West Bank, a policy now called "isolation," the Sharon-Peres government and the Olmert-Peres government that succeeded it carried out the bantustan program in the West Bank. The Jordan Valley was separated from the rest of the West Bank; the south was severed from the north; and all three areas were severed from East Jerusalem. The "two states for two peoples" plan gave way to a "five states for two peoples" plan: one contiguous state, surrounded by settlement blocs, for Israel, and four isolated enclaves for the Palestinians.' (Eldar 2007)

- 'During the early days of the occupation a handful of senior Israeli officials and army officers advocated unilateral plans for a Palestinian satellite mini-state, autonomous region, or "canton" — Bantustan actually — in the northern half of the West Bank, but the policymakers would have none of this.' (Raz 2020, p. 278)

- Palestinian autonomy under Israeli rule, he added, 'would be identified as...some kind of South African Bantustan'. (Gorenberg 2006, p. 153; Cook 2013)

- Called the Wachman (Avraham Wachman, a professor of architecture) or Wachman-Sharon plan

- "What is Begin offering us now? Bantustans. Even less than Bantustans; Swaziland has more rights than we would have" (Arafat 1978)

- Ciskei's Israeli representative Yosef Schneider, during the pairing ceremony, remarked, "It is symbolic that no country in the world (except South Africa) recognizes Ciskei, just as there is no country in the world that recognizes the Jewish settlements in Judea and Samaria" (Hunter 1987, pp. 72–80,74).

- "It will be the end of me. I can't go for a Bantustan. Don't push me into a corner, my back's already against the wall. How will I tell my people that you control every entry, from every direction? I'm not in power because of a popular majority, but thanks to the personal credit I've accumulated. For me, this is a disaster, a catastrophe." (Gil 2020, p. 163)

- "In any case, what was on offer at Oslo was a territorially discontinuous Palestinian Bantustan (divided into over sixty disconnected fragments) that would have had no control over water resources, borders, or airspace, much less an independent economy, currency, or financial system, and whose sovereignty, nominal as it was, would be punctuated by heavily fortified Israeli colonies and an autonomous Jewish road network, all of which would be effectively under Israeli army control. Even this, however, was never realized." (Makdisi 2005, pp. 443–461)

- "By December 1999, the Gaza Strip had been divided into three cantons and the West Bank into 227, the majority of which were no larger than two square kilometers in size. Both areas were effectively severed from East Jerusalem. While Palestinians maintained control over many of the cantons and were promised authority over more if not most, Israel maintained jurisdiction over the land areas in between the cantons, which in effect gave Israel control over all the land and its disposition. Hence, the actual amount of land under Palestinian authority proved far less important than the way that land was arranged and controlled." (Roy 2004, pp. 365–403)

- Rabin and Peres were reconciled to the idea that the Palestinians would eventually establish their own independent state even as the Israelis had established theirs. This cannot be said of the new administration headed by Benyamin Netanyahu. On the contrary, the idea of Palestinian independence is clearly anathema to him. Netanyahu keeps saying that he will honor all international agreements made by the previous government. He also makes it plain that he considers the Oslo agreement a grievous, if not criminal, mistake. The most he seems ready to grant the Palestinians is a form of very limited local autonomy in some two or three dozen Bantustan-style enclaves, on less than 10 percent of occupied territory, surrounded by ever-growing Israeli settlements established on expropriated Palestinian land (Elon 1996).

- 'When I was in Israel recently, giving talks on the thirtieth anniversary of the occupation, I quoted a passage about the Bantustans from a standard academic history of South Africa. You didn't have to comment. Everybody who had their eyes open could recognize it. There were many people who just refuse to see what's happening, including most of the doves. But if you pay attention to what's happening, that's the description. So it is absurd for Israel to be to the racist side of South Africa under Apartheid. I assume that sooner or later they will agree to call these things states.' (Chomsky & Barsamian 2001, p. 90)

- "Walaja, a village southeast of Jerusalem on the Green Line, was another example of near complete enclavization similar to Qalqiliya. The wall blocked the sun and there was one checkpoint and gate to enter and exit.." (Peteet 2017, p. 52)

- (1)Jeff Halper arguing that the occupation will be permanent, as opposed to proponents of a Two state solution, wrote in September 2003:'the danger in being for a Palestinian state is that if you don't understand the control mechanisms, then you are actually agitating for a Bantustan. I mean, Sharon also wants a Palestinian state: he wants a state that is completely controlled by Israel. So, if you only look at territory and you don't look at the issue of control you end up advocating a Bantustan.'(Halper 2004, p. 105); (2)'In April he said that Israel would not withdraw from most of the West Bank, would continue to occupy the Jordan River Valley and the roads leading to them, would make no concessions on Jerusalem, would "absolutely not" evacuate a single settlement "at any price" and would not cede control of the West Bank water aquifers. In case that was not sufficiently clear, over the next year he repeatedly said that the Israeli concessions at Oslo, Camp David, and Taba were no longer valid. A number of prominent Israeli analysts commented that Sharon's intentions were to torpedo the diplomatic process, continue the Israeli occupation, and limit the Palestinians to a series of enclaves surrounded by the Israeli settlements; some even wrote that Sharon's long term strategy resembled that of the "Bantustans" created by the South African apartheid regime' (Slater 2020, p. 303).

- 'Maurizio Molinari, che era il corrispondente diplomatico de "La Stampa" quando D'Alema era Presidente del Consiglio, descrive in un suo libro un incontro tra D'Alema ed Ariel Sharon, che ricopriva la carica di Ministro degli Esteri ed era considerato in Europa un personaggio da evitare. "La pace è più importante della sicurezza", aveva affermato il Presidente del Consiglio italiano e Sharon gli aveva risposto che non voleva che Israele diventasse come la Cecoslovacchia del 1938. D'Alema dice di ricordare quelle frasi, ma di avere bene impresse in mente altre parole che furono pronunciate. "Mi ha detto una cosa che ricordo ancora. In quel periodo egli sosteneva che non ci sarà un vero e proprio Stato palestinese, bensì dei territori palestinesi, senza forze di sicurezza ed inclusi nei confini di Israele". Il termine usato da Sharon aveva alquanto spaventato D'Alema. "Egli ha chiarito, e ha usato il termine banthustan, le enclavi dei neri fondate dal governo dell'apartheid in Sud Africa. Io gli ho risposto: non troverà mai una controparte palestinese che firmi un accordo di questo genere".'(IMFA 2006)

- 'In 2003, Prime Minister Ariel Sharon revealed that he relied on South Africa's Bantustan model in constructing a possible "map of a Palestinian state"." (Feld 2014, pp. 99,138)

- Judt, just before his death. stated in an interview that, since his 2003 article, 'everyone from Moshe Arens to Barak to Olmert has admitted that Israel is on the way to a single state with a potential Arab majority in Bantustans unless something happens fast' (Judt & Michaeli 2011; Judt 2003)

- 'It is quite clear that a Palestinian State with so many territorial enclaves will not be able to manage economic functions and administration. Even if its sovereign territory were greater, and even if some of the enclaves were connected into a continued territorial unity, the main communications arteries that are under Israeli dominance running from north to south and from west to east, and those along the Judean Desert that are under Israeli dominance, might perpetuate their spatial fragmentation.' (Efrat 2006, p. 199)

- 'If Ariel Sharon were able to hear the news from the Gaza Strip and West Bank, he would call his loyal aide, Dov Weissglas, and say with a big laugh: "We did it, Dubi." Sharon is in a coma, but his plan is alive and kicking. Everyone is now talking about the state of Hamastan. In his house, they called it a bantustan, after the South African protectorates designed to perpetuate apartheid.' (Eldar 2007)

- "Israeli politicians lost no time exploiting these fears increasingly employing the term Hamastan - a neologism for the concept of a Hamas-dominated Palestinian Islamist theocracy under Iranian tutelage - to describe these circumstances; "before our very eyes", as Netanyahu warned, "Hamastan has been established, the step-child of Iran and the Taliban"." (Ram 2009, p. 82)

- "To make this grid possible, more than 2,710 homes and workplaces in the West Bank have been completely destroyed, and an additional 39,964 others have been damaged, since the beginning of the Intifada." (Haddad 2009, p. 280)

- "At times, the politics of separation/partition has been dressed up as a formula for peaceful settlement at others as a bureaucratic-territorial arrangement of governance, and most recently as a means of unilaterally imposed domination, oppression and fragmentation of the Palestinian people and their land. The Oslo Accords of the 1990s left the Israeli military in control of the interstices of an archipelago of about two hundred separate zones of Palestinian restricted autonomy in the West Bank and Gaza." (Weizman 2012, pp. 10–11)

- The International Fact-Finding Mission on Israeli Settlements noted that "Various sources refer to settlement master plans, including the Allon Plan(1967), the Drobles Plan(1978)–later expanded as the Sharon Plan(1981)– and the Hundred Thousand Plan(1983). Although these plans were never officially approved, they have largely been acted upon by successive Governments of Israel. The mission notes a pattern whereby plans developed for the settlements have been mirrored in Government policy instruments and implemented on the ground." (UNHCR 2013, pp. 6–7)

- "This is not a recipe for a just and durable peace but rather endorses the creation of a 21st century Bantustan in the Middle East. The Palestinian statelet envisioned by the American plan would be scattered archipelagos of non-contiguous territory completely surrounded by Israel, with no external borders, no control over its airspace, no right to a military to defend its security, no geographic basis for a viable economy, no freedom of movement and with no ability to complain to international judicial forums against Israel or the United States." (Lynk 2020)

- "In sum, Israel continues to establish facts on the ground in these sensitive areas, thus undermining a future political settlement in East Jerusalem. Its policies reflect an ongoing effort to clear disputed areas in order to establish or expand settlements; change the demographic composition of East Jerusalem and strengthen Jewish presence, impede the development and expansion of Palestinian neighbourhoods, and prevent the prospects of creating a viable Palestinian capital with territorial contiguity." (NRC 2015, p. 26)

Citations

- Barak 2005, pp. 719–736.

- Baylouny 2009, pp. 39–68.

- Peteet 2016, pp. 247–281.

- Chaichian 2013, pp. 271–319.

- Yiftachel 2016, p. 320.

- Boyle 2011, pp. 13–17, p.60.

- Niksic, Eddin & Cali 2014, p. 1.

- Harris 1984, pp. 169–189.

- Srivastava 2020.

- UNHRC 2020.

- Kelly 2016, pp. 723–745.

- Motro 2005, p. 46.

- Mohammed & Holland 2020.

- Honig-Parnass 2011, p. 206.

- Robinson 2018, p. 292.

- Haaretz 2004.

- Levy 2020.

- Gorenberg 2006, p. 153.

- Slater 2001, pp. 171–199.

- Shany 2019.

- Bowman 2007, pp. 127–135.

- Falah 2005, pp. 1341–1372.

- Taraki 2008, pp. 6–20.

- Gil 2020, p. 162.

- Korn 2013, p. 122.

- Alissa 2013, p. 128.

- Lustick 1988, p. 45.

- Shafir 2017, p. 57.

- Shafir 2017, p. 58.

- Weizman 2012, p. 25.

- Holzman-Gazit 2013, p. 134, n.11.

- Lustick 1997, pp. 35,37.

- Holzman-Gazit 2013, p. 137.

- Abu-Lughod 1981, p. 61(V).

- Gelvin 2007, p. 277.

- Pedahzur 2005, p. 66.

- Goodman 2011, p. 57.

- Reinhart 2006, p. 163.

- Weizman 2006, p. 350.

- Weizman 2006, p. 351, n=50.

- Weizman 2006, p. 349, n=47.

- Adem 2019, pp. 31–32.

- Rahnema 2014.

- Lissoni 2015, pp. 53–55.

- Clarno 2009, pp. 66–67.

- Nassar 1982, pp. 134– 147.

- Hunter 1986, p. 58.

- Wing 2000, p. 255.

- Kretzmer 2002, p. 76.

- Drew 1997, p. 151.

- Parsons 2005, p. 93.

- Moghayer, Daget & Wang 2017, p. 4.

- Burns & Perugini 2016, p. 39.

- Burns & Perugini 2016, p. 41.

- Motro 2005, p. 47.

- Burns & Perugini 2016, p. 40.

- Kamrava 2016, p. 95.

- Finkelstein 2003, p. 177.

- McMahon 2010, pp. 23–24.

- Sabel 2011, p. 25.

- Chomsky & Barsamian 2001, p. 92.

- Goldschmidt 2018, p. 375.

- Marzano 2011, p. 85.

- Molinari 2000, pp. 3–15,13.

- Polakow-Suransky 2010, p. 236.

- Eldar 2007.

- Le More 2005, p. 990.

- Farsakh 2005, p. 231.

- Eldar 2003.

- Machover 2012, p. 55.

- Primor 2002.

- Telhami 2010, p. 83.

- Makdisi 2012, p. 92.

- Harms & Ferry 2017, p. 211.

- Entous 2018.

- Shalev 2017.

- Stock 2019, p. 49.

- Lustick 2005, p. 23.

- Shaul 2020.

- Haddad 2020.

- Kirby 2020.

- Sherwood 2020.

- Ziegler 2003, p. 3.

- Makdisi 2012, pp. 92–93.

- UNCTAD 2013, p. 32.

- Shezaf 2020.

- Rosen & Shaul 2020, p. 15.

- Le More 2008, p. 170.

- Le More 2008, p. 132.

- Hass 2004.

- Blecher 2005.

- Peteet 2017, p. 93.

- Dugard 2007, p. 16.

- Benvenisti 2006.

- Evening Standard 2008.

Sources

- Abu-Lughod, Janet (4 September 1981). "The Fourth United Nations seminar on the Question of Palestine". United Nations. p. 61.

- Adam, Heribert; Moodley, Kogila (2005). Seeking Mandela: Peacemaking Between Israelis and Palestinians. Psychology Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-84472-130-6.

- Adem, Seada Hussein (5 April 2019). Palestine and the International Criminal Court. T.M.C. Asser Press. ISBN 978-94-6265-291-0.

- Alissa, Sufyan (2013). "6: The economics of an independent Palestine". In Hilal, Jamil (ed.). Where Now for Palestine?: The Demise of the Two-State Solution. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84813-801-8.

- Arafat, Yasser (1978). "The PLO Position". Journal of Palestine Studies. 7 (3): 171–174. doi:10.2307/2536214. JSTOR 2536214.

- Arieli, Shaul (November 2017). Messianism Meets Reality The Israeli Settlement Project in Judea and Samaria: Vision or Illusion, 1967-2016 (PDF) (Report). Economic Cooperation Foundation.

- Barak, Oren (November 2005). "The Failure of the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process, 1993-2000". Journal of Peace Research. 42 (6): 719–736. doi:10.1177/0022343305057889. JSTOR 30042415. S2CID 53652363.

- Baylouny, Anne Marie (September 2009). "Fragmented Space and Violence in Palestine". International Journal on World Peace. 26 (3): 39–68. JSTOR 20752894.

- Benvenisti, Meron (26 April 2004). "Bantustan Plan for an apartheid Israel". The Guardian.

- Benvenisti, Meron (28 December 2006). "The temples of the occupation". Haaretz. Archived from the original on 2 December 2008.

- Bevan, Robert (2007). The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War. United Kingdom: Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-186189205-8.

- Blecher, Robert (2005). "Transportational Contiguity". Middle East Report, also at Google books.

- Bowman, Glenn (2007). "Israel's wall and the logic of encystation: Sovereign exception or wild sovereignty?". Focaal-European Journal of Anthropology (50): 127–136.

- Boyle, Francis (2011). The Palestinian Right of Return Under International Law. Clarity Press. ISBN 978-0-932-86393-5.

- Brogan, Patrick (16 June 1967). "Problems of Victory Divide Israel". The Times.

- Burns, Jacob; Perugini, Nicola (2016). "Untangling the Oslo Lines". In Manna, Jumana; Storihle, Sille (eds.). The Goodness Regime (PDF). pp. 38–43.

- Chaichian, Mohammed (2013). "Bantustans, Maquiladoras, and the Separation Barrier Israeli Style". Empires and Walls: Globalization, Migration, and Colonial Domination. BRILL. pp. 271–319. ISBN 978-9-004-26066-5.

- Chomsky, Noam; Barsamian, David (2001). Propaganda and the Public Mind: Conversations with Noam Chomsky. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-745-31788-5.

- Clarno, Andrew James (2009). The Empire's New Walls: Sovereignty, Neo-liberalism, and the Production of Space in Post-apartheid South Africa and Post-Oslo Palestine/Israel (Thesis). pp. 66–67. hdl:2027.42/127105. ISBN 978-1-244-00753-6.

- Cook, Catherine; Hanieh, Adam (2006). "35: Walling in People Walling out Sovereignty". In Beinin, Joel; Stein, Rebecca L. (eds.). The Struggle for Sovereignty: Palestine and Israel, 1993-2005. Stanford University Press. pp. 338–347. ISBN 978-0-8047-5365-4.

- Cook, Jonathan (2013). Disappearing Palestine: Israel's Experiments in Human Despair. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-848-13649-6.

- Displacement and the 'Jerusalem Question': An Overview of the Negotiations over East Jerusalem and Developments on the Ground (PDF) (Report). Norwegian Refugee Council. April 2015.

- Drew, Catriona (1997). "6: Self Determination, Population Transfer and the Middle East Peace Accords". In Bowen, Stephen (ed.). Human Rights, Self-Determination and Political Change in the Occupied Palestinian Territories. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-411-0502-6.

- Dugard, John (29 January 2007). Implementation of General Assembly Resolution 60/251 of 15 March 2006 entitled "Human Rights Council": Report of the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in the Palestinian territories occupied since 1967 (Report). United Nations.

- Dumper, Michael (17 June 2014). Jerusalem Unbound: Geography, History, and the Future of the Holy City. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-53735-3.

- Efrat, Elisha (2006). The West Bank and Gaza Strip: A Geography of Occupation and Disengagement. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-17217-7.

- Eldar, Akiva (13 May 2003). "Sharon's Bantustans Are Far From Copenhagen's Hope". Haaretz.

- Eldar, Akiva (18 June 2007). "Sharon's Dream". Haaretz.

- Elon, Amos (19 December 1996). "Israel and the End of Zionism". The New York Review of Books.

- Entous, Adam (9 July 2018). "The Maps of Israeli Settlements That Shocked Barack Obama". New Yorker Magazine.

- Falah, Ghazi-Walid (2005). "The Geopolitics of 'Enclavisation' and the Demise of a Two-State Solution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict". Third World Quarterly. 26 (8): 1341–1372. doi:10.1080/01436590500255007. JSTOR 4017718. S2CID 154697979.

- Farsakh, Leila (Spring 2005). "Independence, Cantons, or Bantustans: Whither the Palestinian State?". Middle East Journal. 59 (2): 230–245. doi:10.3751/59.2.13. JSTOR 4330126.

- Feld, Marjorie N. (2014). Nations Divided: American Jews and the Struggle over Apartheid. Springer. ISBN 978-1-137-02972-0.

- Finkelstein, Norman G. (2003). Image and Reality of the Israel-Palestine Conflict (2nd ed.). Verso. ISBN 978-1-859-84442-7.

- Forced Population Transfer: the Case of Palestine, Segregation, Fragmentation and Isolation (PDF) (Report). BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency and Refugee Rights. February 2020.

- Fragmenting Palestine: Formulas for Partition since the British Mandate (PDF) (Report). PASSIA. May 2013.

- Gelvin, James L. (2007). The Israel-Palestine Conflict: One Hundred Years of War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88835-6.

- "George Bush pledges for Middle East peace within a year". Evening Standard. 11 January 2008.

- Ghandour-Demiri, Nada (2016). "Israel-Palestine: An Archipelago of (In)security". In Cavelty, Myriam Dunn; Balzacq, Thierry (eds.). Routledge Handbook of Security Studies (2nd ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-62091-4.

- Gil, Avi (2020). Shimon Peres: An Insider's Account of the Man and the Struggle for a New Middle East. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-755-61703-6.

- Goldschmidt, Arthur, Jr (2018). A Concise History of the Middle East. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-97515-8.

- Goodman, Hirsh (2011). The Anatomy of Israel's Survival. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-610-39083-5.

- Gorenberg, Gershom (2006). The Accidental Empire: Israel and the Birth of the Settlements, 1967-1977. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-1-466-80054-0.

- Haddad, Mohammed (26 June 2020). "Palestine and Israel: Mapping an annexation". Al Jazeera.

- Haddad, Toufic (2009). "Gaza: Birthing a Bantustan". In Tikva, Honig-Parnass; Haddad, Toufic (eds.). Between the Lines: Israel, the Palestinians, and the U.S. War on Terror. Haymarket Books. pp. 280–290 2. ISBN 978-1-608-46047-2.

- Hajjar, Lisa (2001). "Law against Order: Human Rights Organizations and (versus?) the Palestinian Authority". University of Miami Law Review. 56 (1).

- Halbfinger, David M.; Rasgon, Adam (19 June 2020). "As Annexation Looms, Israeli Experts Warn of Security Risks". The New York Times.

- Halper, Jeff (Winter 2004). "Israel and Empire". Journal of Palestine Studies. 33 (2): 105–106.

- Harker, Christopher (2020). Spacing Debt: Obligations, Violence, and Endurance in Ramallah, Palestine. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-147801247-4.

- Harms, Gregory; Ferry, Todd M. (2017). The Palestine-Israel Conflict: A Basic Introduction 4th Ed. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-2378-7.

- Harris, Brice, Jr (Summer 1984). "The South Africanization of Israel". Arab Studies Quarterly. 6 (3): 169–189. JSTOR 41857718.

- Hass, Amira (29 November 2004). "Donor Countries Won't Fund Israeli-planned Separate Roads for Palestinians". Haaretz.

- Hass, Amira (15 September 2018). "With Oslo, Israel's Intention Was Never Peace or Palestinian Statehood". Haaretz.

- Holzman-Gazit, Dr Yifat (28 February 2013). Land Expropriation in Israel: Law, Culture and Society. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4094-9592-5.

- Honig-Parnass, Tikva (2011). The False Prophets of Peace: Liberal Zionism and the Struggle for Palestine. Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-608-46214-8.

- Hunter, Jane (Spring 1986). "Israel and the Bantustans". Journal of Palestine Studies. 15 (3): 53–89. doi:10.2307/2536750. JSTOR 2536750.

- Hunter, Jane (1987). Israeli Foreign Policy: South Africa and Central America. South End Press. ISBN 978-0-896-08285-4.

- Indyk, Martin (February 2020). "Trump's Unfair Middle East Plan Leaves Nothing to Negotiate". Foreign Affairs.

- "Intervista". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 26 May 2006.

- "Israeli annexation of parts of the Palestinian West Bank would break international law – UN experts call on the international community to ensure accountability". UNHRC. 16 June 2020.

- ITAN: Integrated Territorial Analysis of the Neighbourhoods. Scientific Report – Annexes; Applied Research 2013/1/22 Final Report (PDF) (Report). 11 March 2015. p. 889.

- Judt, Tony (23 October 2003). "Israel: The Alternative". The New York Review of Books.

- Judt, Tony; Michaeli, Merav (14 September 2011). "Tony Judt's Final Word on Israel". The Atlantic.

- Kamrava, Mehran (2016). The Impossibility of Palestine: History, Geography, and the Road Ahead. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22085-8.

- Kelly, Jennifer Lynn (September 2016). "Asymmetrical Itineraries: Militarism, Tourism, and Solidarity in Occupied Palestine" (PDF). American Quarterly. 68 (3): 723–745. doi:10.1353/aq.2016.0060. S2CID 151482682.

- Kirby, Jen (13 July 2020). "Israel's West Bank annexation plan and why it's stalled, explained by an expert". Vox.

- Korn, Alina (2013). "6: The Ghettoization of the Palestinians". In Lentin, Ronit (ed.). Thinking Palestine. Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-84813-789-9.

- Kretzmer, David (25 April 2002). The Occupation of Justice: The Supreme Court of Israel and the Occupied Territories. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-5337-7.

- Le More, Anne (October 2005). "Killing with Kindness: Funding the Demise of a Palestinian State". International Affairs. 81 (5): 981–999. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2005.00498.x. JSTOR 3569071.

- Le More, Anne (31 March 2008). International Assistance to the Palestinians after Oslo: Political guilt, wasted money. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-05232-5.

- Levy, Daniel (30 January 2020). "Don't Call It a Peace Plan". The American Prospect.

- Liel, Alon (2020). "Trump's "Deal of the Century" Is Modeled on South African Apartheid". Palestine-Israel Journal of Politics, Economics and Culture. 25 (1&2): 100–120.

- Lissoni, Arianna (2015). "Apartheid's Little Israel: Bophuthatswana". In Jacobs, Sean; Soske, Jon (eds.). Apartheid Israel: The Politics of an Analogy. Haymarket Books. pp. 53–66. ISBN 978-1-608-46519-4.

- Loewenstein, Antony; Moor, Ahmed (25 March 2013). After Zionism: One State for Israel and Palestine. Saqi. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-86356-739-1.

- Lustick, Ian (1988). For the Land and the Lord: Jewish Fundamentalism in Israel. Council on Foreign Relations.

- Lustick, Ian (1997). "Has Israel Annexed East Jerusalem?" (PDF). Middle East Policy. 5 (1): 34–45. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4967.1997.tb00247.x.

- Lustick, Ian (2005). "The One-State Reality: Reading the Trump-Kushner Plan as a Morbid Symptom". The Arab World Geographer. 23 (1): 23.

- Lynk, Michael (31 January 2020). "UN expert alarmed by 'lopsided' Trump plan, says will entrench occupation". UNHCR.

- Machover, Moshé (2012). Israelis and Palestinians: Conflict and Resolution. Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-608-46148-6.

- Makdisi, Saree (2005). "Said, Palestine, and the Humanism of Liberation". Critical Inquiry. 31 (2): 443–461. doi:10.1086/430974. JSTOR 430974. S2CID 154951084.

- Makdisi, Saree (2012). Palestine Inside Out: An Everyday Occupation. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-06996-9.

- Marzano, Arturo (Spring 2011). "Italian Foreign Policy towards Israel: The Turning Point of the Berlusconi Government (2001––2006)". Israel Studies. 16 (1): 79–103.

- McMahon, Sean F. (2010). The Discourse of Palestinian-Israeli Relations: Persistent Analytics and Practices. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-20204-0.

- Mendel, Yonatan (June 2013). "New Jerusalem". New Left Review. No. 81.

- Moghayer, Taher J.T.; Daget, Yidnekachew Tesmamma; Wang, Xingping (2017). "Challenges of urban planning in Palestine". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 81 (1): 1–5. Bibcode:2017E&ES...81a2152M. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/81/1/012152.

- Mohammed, Arshad; Holland, Steve (11 February 2020). "Palestinians' Abbas, at U.N., says U.S. offers Palestinians 'Swiss cheese' state". Reuters.

- Molinari, Maurizio (2000). L'interesse nazionale: dieci storie dell'Italia nel mondo. Laterza. ISBN 978-8-842-06063-5.

- Motro, Shari (September–October 2005). "Lessons From the Swiss Cheese Map". Legal Affairs. pp. 46–50. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- Nassar, Prof Jamal R. (15 March 1982). "The Fourth United Nations seminar on the Question of Palestine". United Nations. p. 134.

- Niksic, Orhan; Eddin, Nur Nasser; Cali, Massimiliano (10 July 2014). Area C and the Future of the Palestinian Economy. World Bank Publications. ISBN 978-1-464-80196-9.

- The Palestinian economy in East Jerusalem: Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration (PDF) (Report). UNCTAD. 2013.

- Parsons, Nigel (2005). The Politics of the Palestinian Authority: From Oslo to Al-Aqsa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-94523-7.

- Pedahzur, Ami (2005). Suicide Terrorism. Polity Press. ISBN 978-0-745-63383-1.

- Pedatzur, Reuven (1995). "Coming Back Full Circle: The Palestinian Option in 1967". Middle East Journal. 49 (2): 269–291. JSTOR 4328804.

- Peteet, Julie (Winter 2016). "The Work of Comparison: Israel/Palestine and Apartheid". Anthropological Quarterly. 89 (1): 247–281. doi:10.1353/anq.2016.0015. JSTOR 43955521. S2CID 147128703.

- Peteet, Julie (2017). Space and Mobility in Palestine. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-02511-1.

- Polakow-Suransky, Sasha (2010). The Unspoken Alliance: Israel's Secret Relationship with Apartheid South Africa. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-37925-2.

- "Powell Warns Against Division of West Bank Into 'Bantustans'". Haaretz. 6 June 2004.

- Primor, Avi (18 September 2002). "Sharon's South African strategy". Haaretz.

- Primor, Avi (2003). Terror als Vorwand: Die Sprache der Gewalt. Düsseldorf: Droste. ISBN 978-3-770-01183-4.

- Rahnema, Saeed (6 October 2014). "Gaza and the West Bank: Israel's two approaches and Palestinians' two bleak choices". Open Canada, Canadian International Council.

- Ram, Haggai (2009). Iranophobia: The Logic of an Israeli Obsession. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-804-77119-1.

- Raz, Avi (2020). "Dodging the Peril of Peace: Israel and the Arabs in the Aftermath of the 1967 War". In Hanssen, Jens; Ghazal, Amal N. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Contemporary Middle-Eastern and North African History. Oxford University Press. pp. 269–291. ISBN 978-0-199-67253-0.

- Reinhart, Tanya (2006). The Road Map to Nowhere: Israel/Palestine Since 2003. = Verso Books. ISBN 978-1-844-67076-5.

- Report of the independent international fact-finding mission to investigate the implications of the Israeli settlements on the civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of the Palestinian people throughout the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem (PDF) (Report). UNHCR. 7 February 2013. pp. 6–7.

- Robinson, Glenn E. (2018). "Chapter 6 Palestine". In Gasiorowski, Mark; L.Yom, Sean (eds.). The Government and Politics of the Middle East and North Africa. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-97411-3.

- Rokem, Jonathan (20 January 2013). "Politics and Conflict in a Contested City". Bulletin du Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem (online) (23): 719–736.

- Rosen, Maya; Shaul, Yehuda (December 2020). Highway to Annexation: Israeli Road and Transportation Infrastructure Development in the West Bank (PDF) (Report). The Israeli Centre for Public Affairs & Breaking the Silence. p. 39.

- Roy, Sara (2004). "The Palestinian-Israeli Conflict and Palestinian Socioeconomic Decline: A Place Denied". International Journal of Politics, Culture, and Society. 17 (3): 365–403. doi:10.1023/B:IJPS.0000019609.37719.99. JSTOR 20007687. S2CID 145653769.

- Rubenberg, Cheryl, ed. (2010). Encyclopedia of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: A-H (3rd ed.). Lynne Rienner Publishers. ISBN 978-1-588-26686-6.

- Sabel, Robbie (Fall 2011). "The Campaign to Delegitimize Israel with the False Charge of Apartheid". Jewish Political Studies Review. 23 (3/4): 18–31. JSTOR 41575857.

- Shafir, Gershon (2017). A Half Century of Occupation: Israel, Palestine, and the World's Most Intractable Conflict. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-29350-2.

- Shain, Milton (2019). "The Roots of Anti-Zionism in South Africa and the Delegitimization of Israel". In Rosenfeld, Alvin H. (ed.). Anti-Zionism and Antisemitism: The Dynamics of Delegitimization. Indiana University Press. pp. 397–413. ISBN 978-0-253-03874-6.

- Shalev, Chemi (6 June 2017). "Netanyahu's Blueprint for a Palestinian Bantustan". Haaretz.

- Shany, Yuval (6 May 2019). "Israel's New Plan to Annex the West Bank: What Happens Next?". Lawfare.