Pankration

Pankration (/pænˈkreɪtiɒn, -ˈkreɪʃən/; Greek: παγκράτιον) was a sporting event introduced into the Greek Olympic Games in 648 BC and was an empty-hand submission sport with scarcely any rules. The athletes used boxing and wrestling techniques, but also others, such as kicking and holds, joint-locks and chokes on the ground making it similar to modern MMA.[1] The term comes from the Greek παγκράτιον [paŋkrátion], literally meaning "all of power" from πᾶν (pan) "all" and κράτος (kratos) "strength, might, power".[2]

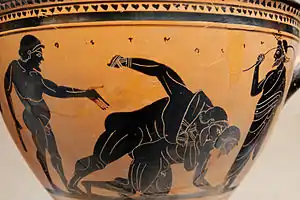

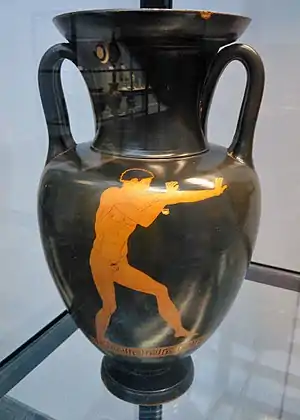

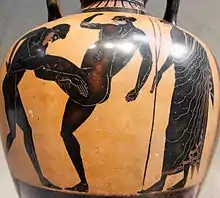

Two athletes competing in the pankration. Panathenaic amphora, made in Athens in 332–331 BC, during the archonship of Niketes. From Capua | |

| Focus | Boxing and Wrestling |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Ancient Greece |

| Olympic sport | Introduced in 648 BC in the 33rd Olympiad |

History

In Greek mythology, it was said that the heroes Heracles and Theseus invented pankration as a result of using both wrestling and boxing in their confrontations with opponents. Theseus was said to have utilized his extraordinary pankration skills to defeat the dreaded Minotaur in the Labyrinth. Heracles was said to have subdued the Nemean lion using pankration, and was often depicted in ancient artwork doing that.[1] In this context, pankration was also referred to as pammachon or pammachion (πάμμαχον or παμμάχιον), meaning "total combat", from πᾶν-, pān-, "all-" or "total", and μάχη, machē, "matter". The term pammachon was older,[3] and would later become used less than the term pankration.

The mainstream academic view has been that pankration developed in the archaic Greek society of the 7th century BC, whereby, as the need for expression in violent sport increased, pankration filled a niche of "total contest" that neither boxing nor wrestling could.[4] However, some evidence suggests that pankration, in both its sporting form and its combative form, may have been practiced in Greece already from the second millennium BC.[5]

Pankration, as practiced in historical antiquity, was an athletic event that combined techniques of both boxing (pygmē/pygmachia – πυγμή/πυγμαχία) and wrestling (palē – πάλη), as well as additional elements, such as the use of strikes with the legs, to create a broad fighting sport similar to today's mixed martial arts competitions. There is evidence that, although knockouts were common, most pankration competitions were decided on the basis of submission (giving up). Pankratiasts were highly skilled grapplers and were extremely effective in applying a variety of takedowns, chokes and joint locks. In extreme cases a pankration competition could even result in the death of one of the opponents, which was considered a win.

However, pankration was more than just an event in the athletic competitions of the ancient Greek world; it was also part of the arsenal of Greek soldiers – including the famous Spartan hoplites and Alexander the Great's Macedonian phalanx. It is said that the Spartans at their immortal stand at Thermopylae fought with their bare hands and teeth once their swords and spears broke.[6] Herodotus mentions that in the battle of Mycale between the Greeks and the Persians in 479 BC, those of the Greeks who fought best were the Athenians, and the Athenian who fought best was a distinguished pankratiast, Hermolycus, son of Euthynus.[7] Polyaemus describes King Philip II, the father of Alexander the Great, practicing with another pankratiast while his soldiers watched.[1]

The feats of the ancient pankratiasts became legendary in the annals of Greek athletics. Stories abound of past champions who were considered invincible beings. Arrhichion, Dioxippus, Polydamas of Skotoussa and Theogenes (often referred to as Theagenes of Thasos after the first century AD) are among the most highly recognized names. Their accomplishments defying the odds were some of the most inspiring of ancient Greek athletics and they served as inspiration to the Hellenic world for centuries, as Pausanias,[8] the ancient traveller and writer indicates when he re-tells these stories in his narrative of his travels around Greece.

Dioxippus was an Athenian who had won the Olympic Games in 336 BC, and was serving in Alexander the Great's army in its expedition into Asia. As an admired champion, he naturally became part of the circle of Alexander the Great. In that context, he accepted a challenge from one of Alexander's most skilled soldiers named Coragus to fight in front of Alexander and the troops in armed combat. While Coragus fought with weapons and full armour, Dioxippus showed up armed only with a club and defeated Coragus without killing him, making use of his pankration skills. Later, however, Dioxippus was framed for theft, which led him to commit suicide.

In an odd turn of events, a pankration fighter named Arrhichion (Ἀρριχίων) of Phigalia won the pankration competition at the Olympic Games despite being dead. His opponent had locked him in a chokehold and Arrhichion, desperate to loosen it, broke his opponent's toe (some records say his ankle). The opponent nearly passed out from pain and submitted. As the referee raised Arrhichion's hand, it was discovered that he had died from the chokehold. His body was crowned with the olive wreath and returned to Phigaleia as a hero.

By the Imperial Period, the Romans had adopted the Greek combat sport (spelled in Latin as pancratium) into their Games.[9] In 393 A.D., the pankration, along with gladiatorial combat and all pagan festivals, was abolished by edict by the Christian Byzantine Emperor Theodosius I. Pankration itself was an event in the Olympic Games for some 1,400 years.

Pausanias mention the wrestler Leontiscus (Λεοντίσκος) from Messene. He wrote that his technique of wrestling was similar to the pankration of Sostratus the Sicyonian, because Leontiscus did not know how to throw his opponents, but won by bending their fingers.[10]

Structure of the ancient competition

There were neither weight divisions nor time limits in pankration competitions. However, there were two or three age groups in the competitions of antiquity. In the Olympic Games specifically there were only two such age groups:. men (andres – ἄνδρες) and boys (paides – παῖδες). The pankration event for boys was established at the Olympic Games in 200 B.C.. In pankration competitions, referees were armed with stout rods or switches to enforce the rules. In fact, there were only two rules regarding combat: no eye gouging or biting.[11] Sparta was the only place eye gouging and biting was allowed.[12] The contest itself usually continued uninterrupted until one of the combatants submitted, which was often signalled by the submitting contestant raising his index finger. The judges appear, however, to have had the right to stop a contest under certain conditions and award the victory to one of the two athletes; they could also declare the contest a tie.[5]

Pankration competitions were held in tournaments, most being outside of the Olympics. Each tournament began with a ritual which would decide how the tournament would take place.. Grecophone satirist Lucian describes the process in detail:

A sacred silver urn is brought, in which they have put bean-size lots. On two lots an alpha is inscribed, on two a beta, and on another two a gamma, and so on. If there are more athletes, two lots always have the same letter. Each athlete comes forth, prays to Zeus, puts his hand into the urn and draws out a lot. Following him, the other athletes do the same. Whip bearers are standing next to the athletes, holding their hands and not allowing them to read the letter they have drawn. When everyone has drawn a lot, the alytarch,[n 1] or one of the Hellanodikai walks around and looks at the lots of the athletes as they stand in a circle. He then joins the athlete holding the alpha to the other who has drawn the alpha for wrestling or pankration, the one who has the beta to the other with the beta, and the other matching inscribed lots in the same manner.[13]

This process was apparently repeated every round until the finals.

If there was an odd number of competitors, there would be a bye (ἔφεδρος – ephedros "reserve") in every round until the last one. The same athlete could be an ephedros more than once, and this could of course be of great advantage to him as the ephedros would be spared the wear and tear of the rounds imposed on his opponent(s). To win a tournament without being an ephedros in any of the rounds (ἀνέφεδρος – anephedros "non-reserve") was thus an honorable distinction.

There is evidence that the major Games in Greek antiquity easily had four tournament rounds, that is, a field of sixteen athletes. Xanthos mentions the largest number—nine tournament rounds. If these tournament rounds were held in one competition, up to 512 contestants would participate in the tournament, which is difficult to believe for a single contest. Therefore, one can hypothesize that the nine rounds included those in which the athlete participated during regional qualification competitions that were held before the major games. Such preliminary contests were held prior to the major games to determine who would participate in the main event. This makes sense, as the 15–20 athletes competing in the major games could not have been the only available contestants. There is clear evidence of this in Plato, who refers to competitors in the Panhellenic Games, with opponents numbering in the thousands. Moreover, in the first century A.D., the Greco-Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria—who was himself probably a practitioner of pankration—makes a statement that could be an allusion to preliminary contests in which an athlete would participate and then collect his strength before coming forward fresh in the major competition.[5]

Techniques

The athletes engaged in a pankration competition – i.e., the pankratiasts (sg. παγκρατιαστής, pl. παγκρατιασταί[14] – employed a variety of techniques in order to strike their opponent as well as take him to the ground in order to use a submission technique. When the pankratiasts fought standing, the combat was called Anō Pankration (ἄνω παγκράτιον, "upper Pankration");[n 2] and when they took the fight to the ground, that stage of pankration competition was called katō pankration (κάτω παγκράτιον "lower pankration"). Some of the techniques that would be applied in anō pankration and katō pankration, respectively, are known to us through depictions on ancient pottery and sculptures, as well as in descriptions in ancient literature. There were also strategies documented in ancient literature that were meant to be used to obtain an advantage over the competitor. For illustration purposes, below are examples of striking and grappling techniques (including examples of counters), as well as strategies and tactics, that have been identified from the ancient sources (visual arts or literature).

Fighting stance

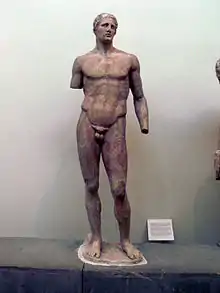

The pankratiast faces his opponent with a nearly frontal stance—only slightly turned sideways. This is an intermediate directional positioning, between the wrestler's more frontal positioning and the boxer's more sideways stance and is consistent with the need to preserve both the option of using striking and protecting the center line of the body and the option of applying grappling techniques. Thus, the left side of the body is slightly forward of the right side of the body and the left hand is more forward than the right one. Both hands are held high so that the tips of the fingers are at the level of the hairline or just below the top of the head. The hands are partially open, the fingers are relaxed, and the palms are facing naturally forward, down, and slightly towards each other. The front arm is nearly fully extended but not entirely so; the rear arm is more cambered than the front arm, but more extended than a modern-day boxer's rear arm. The back of the athlete is somewhat rounded, but not as much as a wrestler's would be. The body is only slightly leaning forward.

The weight is virtually all on the back (right) foot with the front (left) foot touching the ground with the ball of the foot. It is a stance in which the athlete is ready at the same time to give a kick with the front leg as well as defend against the opponent's low level kicks by lifting the front knee and blocking. The back leg is bent for stability and power and is facing slightly to the side, to go with the slightly sideways body position. The head and torso are behind the protecting two upper limbs and front leg.[5]

Punch and other hand strikes

Pankration uses boxing punches and other ancient boxing hand strikes.[15]

Strikes with the legs

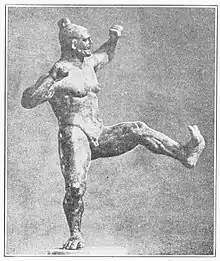

Strikes delivered with the legs were an integral part of pankration and one of its most characteristic features. Kicking well was a great advantage to the pankratiast. Epiktētos is making a derogatory reference to a compliment one may give another: "μεγάλα λακτίζεις" ("you kick great"). Moreover, in an accolade to the fighting prowess of the pankratiast Glykon from Pergamo, the athlete is described as "wide foot". The characterization comes actually before the reference to his "unbeatable hands", implying at least as crucial a role for strikes with the feet as with the hands in pankration. That proficiency in kicking could carry the pankratiast to victory is indicated in a sarcastic passage of Galen, where he awards the winning prize in pankration to a donkey because of its excellence in kicking.

Straight kick to the stomach

The straight kick with the bottom of the foot to the stomach (γαστρίζειν/λάκτισμα εἰς γαστέραν – gastrizein or laktisma eis gasteran, "kicking in the stomach") was apparently a common technique, given the number of depictions of such kicks on vases. This type of kick is mentioned by Lucian.

Counter: The athlete sidesteps the oncoming kick to the inside of the opponent's leg. He catches and lifts the heel/foot of the planted leg with his rear hand and with the front arm goes under the knee of the kicking leg, hooks it with the nook of his elbow, and lifts while advancing to throw the opponent backward. The athlete executing the counter has to lean forward to avoid hand strikes by the opponent. This counter is shown on a Panathenaic amphora now in Leiden. In another counter, the athlete sidesteps, but now to the outside of the oncoming kick and grasps the inside of the kicking leg from behind the knee with his front hand (overhand grip) and pulls up, which tends to unbalance the opponent so that he falls backward as the athlete advances. The back hand can be used for striking the opponent while he is preoccupied maintaining his balance.[5]

Locking techniques

Arm locks

Arm locks can be performed in many different situations using many different techniques.

Single shoulder lock (overextension)

The athlete is behind the opponent and has him leaning down, with the right knee of the opponent on the ground. The athlete has the opponent's right arm straightened out and extended maximally backward at the shoulder joint. With the opponent's right arm across his own torso, the athlete uses his left hand to keep the pressure on the opponent's right arm by grabbing and pressing down on it just above the wrist. The right hand of the athlete is pressing down at the (side of) the head of the opponent, thus not permitting him to rotate to his right to relieve the pressure on his shoulder. As the opponent could escape by lowering himself closer to the ground and rolling, the athlete steps with his left leg over the left leg of the opponent and wraps his foot around the ankle of the opponent stepping on his instep, while pushing his body weight on the back of the opponent.

Single arm bar (elbow lock)

In this technique, the position of the bodies is very similar to the one described just above. The athlete executing the technique is standing over his opponent's back, while the latter is down on his right knee. The left leg of the athlete is straddling the left thigh of the opponent—the left knee of the opponent is not on the floor—and is trapping the left foot of the opponent by stepping on it. The athlete uses his left hand to push down on the side/back of the head of the opponent while with his right hand he pulls the opponent's right arm back, against his midsection. This creates an arm bar on the right arm with the pressure now being mostly on the elbow. The fallen opponent cannot relieve it, because his head is being shoved the opposite way by the left hand of the athlete executing the technique.

Arm bar – shoulder lock combination

In this technique, the athlete is again behind his opponent, has the left arm of his opponent trapped, and is pulling back on his right arm. The trapped left arm is bent, with the fingers and palm trapped inside the armpit of the athlete. To trap the left arm, the athlete has pushed (from outside) his own left arm underneath the left elbow of the opponent. The athlete's left hand ends up pressing down on the scapula region of his opponent's back. This position does not permit the opponent to pull out his hand from the athlete's armpit and puts pressure on the left shoulder. The right arm of the athlete is pulling back at the opponent's right wrist (or forearm). In this way, the athlete keeps the right arm of his opponent straightened and tightly pulled against his right hip/lower abdomen area, which results in an arm bar putting pressure on the right elbow. The athlete is in full contact on top of the opponent, with his right leg in front of the right leg of the opponent to block him from escaping by rolling forward.[5]

Leg locks

Pankratiasts would refer to two different kinds of athletes; "the one who wrestles with the heel" and "the one who wrestles with the ankle" which indicates early knowledge of what is now known as the Straight Ankle-Lock, and the Heel Hook.[16]

Tracheal grip choke

In executing this choking technique (ἄγχειν – anchein), the athlete grabs the tracheal area (windpipe and "Adam's apple") between his thumb and his four fingers and squeezes. This type of choke can be applied with the athlete being in front or behind his opponent. Regarding the hand grip to be used with this choke, the web area between the thumb and the index finger is to be quite high up the neck and the thumb is bent inward and downward, "reaching" behind the Adam's apple of the opponent. It is unclear if such a grip would have been considered gouging and thus illegal in the Panhellenic Games.

Tracheal dig using the thumb

The athlete grabs the throat of the opponent with the four fingers on the outside of the throat and the tip of the thumb pressing in and down the hollow of the throat, putting pressure on the trachea.

Choke from behind with the forearm

The Rear naked choke (RNC) is a chokehold in martial arts applied from an opponent's back. Depending on the context, the term may refer to one of two variations of the technique, either arm can be used to apply the choke in both cases. The term rear naked choke likely originated from the technique in Jujutsu and Judo known as the "Hadaka Jime", or "Naked Strangle." The word "naked" in this context suggests that, unlike other strangulation techniques found in Jujutsu/Judo, this hold does not require the use of a keikogi ("gi") or training uniform.

The choke has two variations:[1] in one version, the attacker's arm encircles the opponent's neck and then grabs his own biceps on the other arm (see below for details); in the second version, the attacker clasps his hands together instead after encircling the opponent's neck. These are deadly moves.

Counter: A counter to the choke from behind involves the twisting of one of the fingers of the choking arm. This counter is mentioned by Philostratus. In case the choke was set together with a grapevine body lock, another counter was the one applied against that lock; by causing enough pain to the ankle of the opponent, the latter could give up his choke.[5]

Heave from a reverse waist lock

From a reverse waist lock set from the front, and staying with hips close to the opponent, the athlete lifts and rotates his opponent using the strength of his hips and legs (ἀναβαστάσαι εἰς ὕψος – anabastasai eis hypsos, "high lifting"). Depending on the torque the athlete imparts, the opponent becomes more or less vertically inverted, facing the body of the athlete. If however the reverse waist lock is set from the back of the opponent, then the latter would face away from the athlete in the inverted position.

To finish the attack, the athlete has the option of either dropping his opponent head-first to the ground, or driving him into the ground while retaining the hold. To execute the latter option, the athlete bends one of his legs and goes down on that knee while the other leg remains only partially bent; this is presumably to allow for greater mobility in case the "pile driver" does not work. Another approach emphasizes less putting the opponent in an inverted vertical position and more the throw; it is shown in a sculpture in the metōpē (μετώπη) of the Hephaisteion in Athens, where Theseus is depicted heaving Kerkyōn.

Heave from a waist lock following a sprawl

The opponents are facing in opposite directions with the athlete at a higher level, over the back of his opponent. The athlete can get in this position after making a shallow sprawl to counter a tackle attempt. From here the athlete sets a waist lock by encircling, from the back, the torso of the opponent with his arms and securing a "handshake" grip close to the abdomen of the opponent. He then heaves the opponent back and up, using the muscles of his legs and his back, so that the opponent's feet rise in the air and he ends up inverted, perpendicular to the ground, and facing away from the athlete. The throw finishes with a "pile driver" or, alternatively, with a simple release of the opponent so that he falls to the ground.

Heave from a waist lock from behind

The athlete passes to the back of his opponent, secures a regular waist lock, lifts and throws/ drops the opponent backwards and sideways. As a result of these moves, the opponent would tend to land on his side or face down. The athlete can follow the opponent to the ground and place himself on his back, where he could strike him or choke him from behind while holding him in the "grapevine" body lock (see above), stretching him face down on the ground. This technique is described by the Roman poet Statius in his account of a match between the hero Tydeus of Thebes and an opponent in the Thebaid. Tydeus is described to have followed this takedown with a choke while applying the "grapevine" body lock on the prone opponent.[5]

Positioning in the skamma (σκάμμα "pit")

As the pankration competitions were held outside and in the afternoon, appropriately positioning one's face vis-a-vis the low sun was a major tactical objective. The pankratiast, as well as the boxer, did not want to have to face the sun, as this would partly blind him to the blows of the opponent and make accurate delivery of strikes to specific targets difficult. Theocritus, in his narration of the (boxing) match between Polydeukēs and Amykos, noted that the two opponents struggled a lot, vying to see who would get the sun's rays on his back. In the end, with skill and cunning, Polydeukēs managed so that Amykos' face was struck with sunlight while his own was in the shade.

While this positioning was of paramount importance in boxing, which involved only upright striking (with the eyes facing straight), it was also important in pankration, especially in the beginning of the competition and as long as the athletes remained standing.

Remaining standing versus going to the ground

The decision to remain standing or go to the ground obviously depended on the relative strengths of the athlete, and differed between anō and katō pankration. However, there are indications that staying on one's feet was generally considered a positive thing, while touching the knee(s) to the ground or being put to the ground was overall considered disadvantageous. In fact, in antiquity as today, falling to one's knee(s) was a metaphor for coming to a disadvantage and putting oneself at risk of losing the fight, as argued persuasively by Michael B. Poliakoff.[3]

Offensive versus reactive fighting

Regarding the choice of attacking into the attack of the opponent versus defending and retreating, there are indications, e.g. from boxing, that it was preferable to attack. Dio Chrysostom notes that retreat under fear tends to result in even greater injuries, while attacking before the opponent strikes is less injurious and could very well end in victory.

Identifying and exploiting the weak side of the opponent

As indicated by Plato in his Laws, an important element of strategy was to understand if the opponent had a weak or untrained side and to force him to operate on that side and generally take advantage of that weakness. For example, if the athlete recognizes that the opponent is strictly right-handed, he could circle away from the right hand of the opponent and towards the left side of the opponent. Moreover, if the opponent is weak in his left-side throws, the athlete could aim to position himself accordingly. Training in ambidexterity was instrumental in both applying this strategy and not falling victim to it.[5]

Preparation and practice

The basic instruction of pankration techniques was conducted by the paedotribae (παιδοτρίβαι, "physical trainers"[17]), who were in charge of boys' physical education.[18] High level athletes were also trained by special trainers who were called gymnastae (γυμνασταί),[18] some of whom had been successful pankration competitors themselves. There are indications that the methods and techniques used by different athletes varied, i.e., there were different styles. While specific styles taught by different teachers, in the mode of Asian martial arts, cannot be excluded, it is very clear (including in Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics) that the objective of a teacher of combat sports was to help each of his athletes to develop his personal style that would fit his strengths and weaknesses.[5]

The preparation of pankratiasts included a very wide variety of methods,[5] most of which would be immediately recognizable by the trainers of modern high level athletes, including competitors in modern mixed martial arts competitions. These methods included among others the periodization of training; a wealth of regimens for the development of strength, speed-strength, speed, stamina, and endurance; specialized training for the different stages of competition (i.e., for anō pankration and katō pankration), and methods for learning and engraining techniques. Among the multitude of the latter were also training tools that appear to be very similar to Asian martial arts Forms or kata, and were known as cheironomia (χειρονομία) and anapale (ἀναπάλη). Punching bags (kōrykos κώρυκος "leather sack") of different sizes and dummies were used for striking practice as well as for the hardening of the body and limbs. Nutrition, massage, and other recovery techniques were used very actively by pankratiasts.

Ancient Olympic pankration champions and famous pankratiasts

- Theagenes of Thasos

- Arrichion

- Kleitomachos

- Polydamas of Skotoussa

- Dioxippus

- Timasitheus of Delphi

- Sostratus of Sicyon

- Hysmon

- Antiochus of Arcadia

- Timanthes of Cleonae[19][20]

- Callias (Καλλίᾳς) of Athens, a statue of him was made by Micon.[21]

- Androsthenes (Ἀνδροσθένης) of Mainalo, son of Lochaeus (Λοχαίος), who won two victories among the men. A statue of him was made by Nicodamus of Mainalo.[21]

- Strato (Στράτων) of Alexandria.[22]

- Caprus (Κάπρος) of Elis [23]

- Aristomenes (Ἀριστομένης) of Rhodes [23]

- Protophanes (Πρωτοφάνης) of Magnesia on the Meander [23]

- Marion (Μαρίων) of Alexandria [23]

- Aristeas (Ἀριστέας) of Stratoniceia [23]

- Nicostratus (Νικόστρατος) of Cilicia [23]

- Artemidorus (Ἀρτεμίδωρος) of Tralles.[24]

- Dorieús, son of Diagoras, or Rhodes[25]

Modern pankration

At the time of the revival of the Olympic Games (1896), pankration was not reinstated as an Olympic event.

Neo-pankration (modern pankration) was first introduced to the martial arts community by Greek-American combat athlete Jim Arvanitis in 1969 and later exposed worldwide in 1973 when he was featured on the cover of Black Belt. Arvanitis continually refined his reconstruction with reference to original sources. His efforts are also considered pioneering in what became mixed martial arts (MMA).[26]

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) does not list pankration among Olympic sports, but the efforts of Savvidis E. A. Lazaros, founder of modern Pankration Athlima, the technical examination programma, the endyma, the shape of the Palaestra and the terminology of Pankration Athlima, in 2010 the sport was accepted by FILA,[27] known today as United World Wrestling, which governs the Olympic wrestling codes, as an associated discipline and a "form of modern Mixed Martial Art".[28] Pankration was first contested at the World Combat Games in 2010.[29] Under UWW the pankration competitions have two styles:

- Pankration Athlima

- Pankration

There are also pro tournaments and federations like Modern Fighting Pankration (MFC). These competitions are similar to professional mixed martial arts. There are many UFC stars with pankration backgrounds like American former UFC 125 lb (57 kg) champion Demetrious Johnson and Russians Ali Bagautinov and UFC Lightweight Champion Khabib Nurmagomedov. Johnson's coach, Matt Hume, is the founder and head trainer of AMC Pankration in Kirkland, Washington.

Pancrase, a Japanese MMA organization, is named in reference to pankration.

A few who currently hold rank in America in pankration: Dave Sixel-9th dan red belt, Sheldon Marr-8th dan red/black belt, Steve Crawford-8th dan red/black belt, Craig Pumphrey-7th dan red/black belt, Ivan Dale-6th dan black belt, Michael Craycraft-3rd dan black belt, Troy McDaniel-3rd dan black belt, Josh Lee-2nd dan black belt, Jason Hatfield-2nd dan black belt, Eric Gregory-1st dan black belt, Kyle Hall-1st dan black belt.

Notes

- ἀλυτάρχης (ἀλύτης and ἄρχω) "rod-ruler, referee"

- However, besides being a stage of combat, anō pankration was often an athletic event in itself, whereby the athletes would not be permitted to take the fight to the ground but had to remain standing throughout the match (somewhat like modern Thai boxing).

References

- Georgiou, Andreas V. "Pankration - A Historical Look at the Original Mixed-Martial Arts Competition".

- "παγκράτιον", Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus project

- Poliakoff, Michael (1986). Studies in the Terminology of Greek Combat Sport. Frankfurt: Hain. ISBN 9783445024879.

- Poliakoff, Combat Sport in the Ancient World

- Georgiou, Andreas V. "Pankration – An Olympic Combat Sport". pankration.info.

- Philostratus, Gymnastikos 11

- Herodotus, The Histories, 9.105

- Pausanias, Description of Greece

- Schmitz, Leonhard (1875). "Pancratium". In John Murray (ed.). A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London. pp. 857‑858.

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.4.3

- Miller, Christopher. "Historical Pankration Project". Retrieved 10 April 2008.

- Gross, Josh (9 June 2016). Ali vs. Inoki: The Forgotten Fight That Inspired Mixed Martial Arts and Launched Sports Entertainment. BenBella Books, Inc. ISBN 9781942952206 – via Google Books.

- Lucian, Hermotimos

- "παγκρατιασταί" on Perseus project

- "Ancient Pankration Techniques".

- https://jitsmagazine.com/submission-history-the-origins-of-the-heelhook/

- παιδοτρίβης, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- Gardiner, Greek Athletic Sports and Festivals

- Suda, § tau.593

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.8.4

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.6.1

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 5.21.9

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 5.21.10

- Pausanias, Description of Greece, 6.14.2

- Grote, George (1852). History of Greece, Vol. 9.

- Corcoran, John (1993). The Original Martial Arts Encyclopedia – Tradition, History, Pioneers. ISBN 0961512636.

- Italo Morello (2008). The Origins of Martial Arts: Pankration. pp. 5–6, 60. ISBN 9781471658617.

- "Pankration". FILA. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- "Associated Sports". FILA. Archived from the original on 12 August 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pankration. |

_Pentathlon.svg.png.webp)