Pardo Brazilians

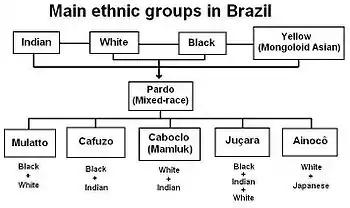

In Brazil, Pardo, (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈpaʁdu] or [ˈpaɾdu]) is an ethnic and skin color category used by the Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) in the Brazilian censuses. The term "pardo" is a complex one, more commonly used to refer to Brazilians of mixed ethnic ancestries. Pardo Brazilians represent a diverse range of skin colors and ethnic backgrounds. They are typically a mixture of Europeans, Sub-Saharan Africans and/or Native Brazilian.[3]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 82,277,333 43.13% of Brazil's population (2010 Census)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Entire country; highest percentages found in the Center-Northern parts of Brazil (North, Northeast, Center-Western and Center-Northern part of the Southeast region). | |

| Languages | |

| Predominantly Portuguese. Before the late-18th century, predominantly língua geral. | |

| Religion | |

| 74% Roman Catholic · 18.2% Protestant · 5.6% irreligious · 2% other denominations (Kardecist, Umbanda, Candomblé)[2] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Brazilians, Afro-Brazilians, Indigenous peoples in Brazil, White Brazilians |

The other categories are branco ("white"), preto ("black"), amarelo ("yellow", meaning East Asians), and indígena ("indigene" or "indigenous person", meaning Amerindians). The term was and is still popular in Brazil.

Pardo was also a casta classification used in Colonial Spanish America from the 16th to 19th centuries. The term pardo was used primarily in small areas of Spanish America whose economy was based on slavery during the Spanish colonization period.

Definitions

According to IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics), pardo is a broad classification that encompasses Multiracial Brazilians such as mulatos and cafuzos, as well as assimilated Amerindians known as caboclos, mixed with Europeans or not. The term "pardo" was first used in a Brazilian census in 1872. The following census, in 1890, replaced the word pardo by mestiço (that of mixed origins). The censuses of 1900 and 1920 did not ask about race, arguing that "the answers largely hid the truth".[4]

In Brazil the word "pardo" has had a general meaning since the beginning of the colonization. In the famous letter by Pero Vaz de Caminha, for example, in which Brazil was first described by the Portuguese, the Native Americans were called "pardo": "Pardo, naked, without clothing".[5]

A reading of colonial wills and testaments also shows it. Diogo de Vasconcelos, a widely known historian from Minas Gerais, mentions, for example, the story of Andresa de Castilhos. According to the information from the 18th century, Andresa de Castilhos was thus described: "I declare that Andresa de Castilhos, pardo woman ... has been freed ... is a descendant of the natives of the land ... I declare that Andresa de Castilhos is the daughter of a white man and a native woman".[6]

The historian Maria Leônia Chaves de Resende also explains that the word pardo was employed to name people with native ancestry or even Native Americans themselves: a Manoel, natural son of Ana carijó, was baptized as a 'pardo'; in Campanha several Native Americans were classified as 'pardo'; the natives João Ferreira, Joana Rodriges and Andreza Pedrosa, for example, were named 'freed pardo'; a Damaso called himself 'freed pardo' of the 'native of the land'; etc.[7]

According to Maria Leônia Chaves de Resende, the growth of the pardo population in Brazil includes the descendants of natives and not only those of African descent: "the growth of the 'pardo' segment had not only to do with the descendants of Africans, but also with the descendants of the natives, in particular the carijós and bastards, included in the condition of 'pardo'".[7]

The American historian Muriel Nazzari specifically pointed out the "pardo" category absorbed those of Native American descent in São Paulo: "This paper seeks to demonstrate that, though many Indians and mestizos did migrate, those who remained in São Paulo came to be classified as pardos"[8]

The question about race reappeared in the 1940 census. In this census, "pardo" was not given as an option, but if the answer was different from the options "white", "black" and "yellow", a horizontal line would be drawn into the "color" box. When the census data was tabulated, all responses with horizontal lines were collected into the single category of "pardo". The term "pardo" was not used as an option as an assurance to the public that census data would not be used for discriminatory purposes due to rising European racist sentiment at the time.[9] In the 1950 census, "pardo" was actually added as a choice of answer.[9] This trend remains, with the exception of the 1970 census, which also did not ask about race.[4]

The 20th century saw a large growth of the pardo population.[4] In 1940, 21.2% of Brazilians were classified as pardos. In 2000, they had increased to 38.5% of the population. This is only partially due to the continuous process of miscegenation in the Brazilian population. Races are molded in accordance with perceptions and ideologies prevalent at each historical moment. In the 20th century, a significant part of the Brazilians who used to self-report as Black in earlier censuses chose to move to the Pardo category. Also a significant part of the population that used to self-report as white also moved to the Pardo category with the growing racial and social awareness, and Magnoli describes this phenomenon as the pardização ("pardoization") of Brazil.[4]

Ancestry

According to an autosomal DNA study (the autosomal study is about the sum of the ancestors of a person, unlike mtDNA or yDNA haplogroup studies, which cover only one single line), the "pardos" in Rio de Janeiro were found to be predominantly European, at roughly 70% (see table). The geneticist Sérgio Pena criticized foreign scholar Edward Telles for lumping "blacks" and "pardos" in the same category, given the predominantly European ancestry of the "pardos" throughout Brazil. According to him, "the autosomal genetic analysis that we have performed in non-related individuals from Rio de Janeiro shows that it does not make any sense to put "blacks" and "pardos" in the same category".[10]

| Genomic ancestry of non-related individuals in Rio de Janeiro[10] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Number of individuals | Amerindian | African | European |

| White | 107 | 6.7% | 6.9% | 86.4% |

| Pardo | 119 | 8.3% | 23.6% | 68.1% |

| Black | 109 | 7.3% | 50.9% | 41.8% |

Another autosomal DNA study has confirmed that the European ancestry is dominant throughout in the Brazilian population, regardless of complexion, "pardos" included. "A new portrayal of each ethnic contribution to the DNA of Brazilians, obtained with samples from the five regions of the country, has indicated that, on average, European ancestors are responsible for nearly 80% of the genetic heritage of the population. The variation between the regions is small, with the possible exception of the South, where the European contribution reaches nearly 90%. The results, published by the scientific magazine 'American Journal of Human Biology' by a team from the Catholic University of Brasília, show that, in Brazil, physical indicators such as skin, eye, and hair color have little to do with the genetic ancestry of each person, as has been shown in previous studies".[11] "Ancestry informative SNPs can be useful to estimate individual and population biogeographical ancestry. The Brazilian population is characterized by a genetic background of three parental populations (European, African, and Brazilian Native Amerindians) with a wide degree and diverse patterns of admixture. In this work we analyzed the information content of 28 ancestry-informative SNPs into multiplexed panels using three parental population sources (African, Amerindian, and European) to infer the genetic admixture in an urban sample of the five Brazilian geopolitical regions. The SNPs assigned apart the parental populations from each other and thus can be applied for ancestry estimation in a three hybrid admixed population. Data was used to infer genetic ancestry in Brazilians with an admixture model. Pairwise estimates of F(st) among the five Brazilian geopolitical regions suggested little genetic differentiation only between the South and the remaining regions. Estimates of ancestry results are consistent with the heterogeneous genetic profile of Brazilian population, with a major contribution of European ancestry (0.771) followed by African (0.143) and Amerindian contributions (0.085). The described multiplexed SNP panels can be useful tool for bio-anthropological studies but it can be mainly valuable to control for spurious results in genetic association studies in admixed populations."[12] It is important to note that "the samples came from free of charge paternity test takers, thus as the researchers made it explicit: "the paternity tests were free of charge, the population samples involved people of variable socioeconomic strata, although likely to be leaning slightly towards the ‘‘pardo’’ group".[12]

According to another autosomal DNA study conducted on a school in the poor periphery of Rio de Janeiro the "pardos" there were found to be on average over 80% European, and the "whites" (who thought of themselves as "very mixed") were found out to carry very little Amerindian and/or African admixtures. "The results of the tests of genomic ancestry are quite different from the self made estimates of European ancestry", say the researchers. In general, the test results showed that European ancestry is far more important than the students thought it would be. The "pardos" for example thought of themselves as 1/3 European, 1/3 African and 1/3 Amerindian before the tests, and yet their ancestry was determined to be at over 80% European.[13][14]

An autosomal study from 2011 (with nearly almost 1000 samples from all over the country, "whites", "pardos" and "blacks") has also concluded that European ancestry is the predominant ancestry in Brazil, accounting for nearly 70% of the ancestry of the population. "In all regions studied, the European ancestry was predominant, with proportions ranging from 60.6% in the Northeast to 77.7% in the South". The "pardos" included were found to be predominantly European in ancestry on average.[15] The 2011 autosomal study samples came from blood donors (the lowest classes constitute the great majority of blood donors in Brazil[16]), and also public health institutions personnel and health students.

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Porto Alegre Sérgio Pena et al. 2011 .[15] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Amerindian | African | European | |

| White | 9.3% | 5.3% | 85.5% | |

| Pardo | 15.4% | 42.4% | 42.2% | |

| Black | 11% | 45.9% | 43.1% | |

| Total | 9.6% | 12.7% | 77.7% | |

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Ilhéus Sérgio Pena et al. 2011 .[15] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Amerindian | African | European | |

| White | 8.8% | 24.4% | 66.8% | |

| Pardo | 11.9% | 28.8% | 59.3% | |

| Black | 10.1% | 35.9% | 53.9% | |

| Total | 9.1% | 30.3% | 60.6% | |

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Belém Sérgio Pena et al. 2011 .[15] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Amerindian | African | European | |

| White | 14.1% | 7.7% | 78.2% | |

| Pardo | 20.9% | 10.6% | 68.6% | |

| Black | 20.1% | 27.5% | 52.4% | |

| Total | 19.4% | 10.9% | 69.7% | |

| Genomic ancestry of individuals in Fortaleza Sérgio Pena et al. 2011 .[15] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Color | Amerindian | African | European | |

| White | 10.9% | 13.3% | 75.8% | |

| Pardo | 12.8% | 14.4% | 72.8% | |

| Black | N.S. | N.S. | N.S | |

History

The formation of the Brazilian people is characterized by the mixing of whites, blacks and Indians.[17] According to geneticist Sérgio Pena "with the exception of immigrants of first or second generation, there is no Brazilian who does not carry a bit of African and Amerindian genetic".[18] "The correlation between color and genomic ancestry is imperfect: at the individual level one cannot safely predict the skin color of a person from his/her level of European, African and Amerindian ancestry nor the opposite. Regardless of their skin color, the overwhelming majority of Brazilians have a high degree of European ancestry. Also, regardless of their skin color, the overwhelming majority of Brazilians have a significant degree of African ancestry. Finally, most Brazilians have a significant and very uniform degree of Amerindian ancestry.

The high ancestral variability observed in whites and blacks suggests that each Brazilian has a singular and quite individual proportion of European, African and Amerindian ancestry in his/her mosaic genomes" (geneticist Sérgio Pena).[19] The colonization of Brazil was characterized by a small proportion of women among the initial settlers.[20] As there was a male predominance in the European contingent present in Brazil, most sexual partners of those settlers were, initially, Amerindian or African women, and, later, mixed-race women.[20] This sexual asymmetry is marked on the genetics of the Brazilian people, regardless of skin color: there is a predominance of European Y chromosomes, and of Amerindian and African MtDNA.[21] Haplogroup frequencies do not determine phenotype nor admixture. They are very general genetic snapshots, primarily useful in examining past population group migratory patterns. Only autosomal DNA testing can reveal admixture structures, since it analyzes millions of alleles from both maternal and paternal sides. Contrary to yDNA or mtDNA, which are focused on one single lineage (paternal or maternal) the autosomal DNA studies profile the whole ancestry of a given individual, being more accurate in describing the complex patterns of ancestry in a given place. In the Brazilian "white" and "pardos" the autosomal ancestry (the sum of the ancestors of a given individual) tends to be largely European, with often a non-European mtDNA (which points to a non-European ancestor somewhere up the maternal line), which is explained by the women marrying newly arrived colonists, during the formation of the Brazilian people.[22]

In the first century of colonization, there was interbreeding between Portuguese males and Amerindian females in Brazil. However, the Amerindian population was decimated by epidemics, wars and slavery.[20] Since 1550, African slaves began to be brought to Brazil in large numbers. Miscegenation between Portuguese males and African females was common. European and Asiatic immigrants who came to Brazil in the 19th and 20th centuries (Portuguese, Italians, Spaniards, Germans, Arab, Japanese, etc.) also participated in the process. Among many of the immigrant groups in Brazil, there was a large predominance of men.

In all Brazilian regions European, African and Amerindian genetic markers are found in the local populations, even though the proportion of each varies from region to region and from individual to individual.[15] However most regions showed basically the same structure, a greater European contribution to the population, followed by African and Native American contributions: "Some people had the vision Brazil was a heterogeneous mosaic. ... Our study proves Brazil is a lot more integrated than some expected".[15] Brazilian homogeneity is, therefore, greater within regions than between them:

| Region[15] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Brazil | 68.80% | 10.50% | 18.50% |

| Northeast of Brazil | 60.10% | 29.30% | 8.90% |

| Southeast Brazil | 74.20% | 17.30% | 7.30% |

| Southern Brazil | 79.50% | 10.30% | 9.40% |

An autosomal study from 2013, with nearly 1,300 samples from all of the Brazilian regions, found a pred. degree of European ancestry combined with African and Native American contributions, in varying degrees. 'Following an increasing North to South gradient, European ancestry was the most prevalent in all urban populations (with values up to 74%). The populations in the North consisted of a significant proportion of Native American ancestry that was about two times higher than the African contribution. Conversely, in the Northeast, Center-West and Southeast, African ancestry was the second most prevalent. At an intrapopulation level, all urban populations were highly admixed, and most of the variation in ancestry proportions was observed between individuals within each population rather than among population'.[23]

| Region | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 17% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 56% | 28% | 16% |

| Central-West Region | 58% | 26% | 16% |

| Southeast Region | 61% | 27% | 12% |

| South Region | 74% | 15% | 11% |

A 2015 autosomal genetic study, which analyzed data of 25 studies of 38 different Brazilian populations concluded that European ancestry accounts for 62% of the heritage of the population, followed by the African (21%) and the Native American (17%). The European contribution is highest in Southern Brazil (77%), the African highest in Northeast Brazil (27%) and the Native American is the highest in Northern Brazil (32%).[24]

| Region[24] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 16% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 58% | 27% | 15% |

| Central-West Region | 64% | 24% | 12% |

| Southeast Region | 67% | 23% | 10% |

| South Region | 77% | 12% | 11% |

Not all descendants of this mixture of peoples are included in the "pardo" category. Since racial classifications in Brazil are based on phenotype, rather than ancestry, a large part of the self-reported white population has African and Amerindian ancestors, as well as a great part of the Black population has large European and Native American contributions.[25] Besides skin color, there are social factors that influence the racial classifications in Brazil, such as social class, wealth, racial prejudice and stigma of being Black, Mulatto or Amerindian.[20]

The following are the results for the different Brazilian censuses, since 1872:

| Brazilian Population, by Race, from 1872 to 20101 (Census Data) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race or Color | Brancos ("whites") | Pardos ("mixed") | Pretos ("blacks") | Caboclos ("indigenous"/"mestizo") | Amarelos ("yellow"/"Asian") | Indigenous | Undeclared | Total |

| 18722 | 3,787,289 | 3,801,782 | 1,954,452 | 386,955 | - | - | - | 9,930,478 |

| 1890 | 6,302,198 | 4,638,4963 | 2,097,426 | 1,295,7953 | - | - | - | 14,333,915 |

| 1940 | 26,171,778 | 8,744,3654 | 6,035,869 | - | 242,320 | - | 41,983 | 41,236,315 |

| 1950 | 32,027,661 | 13,786,742 | 5,692,657 | - | 329,082 | -5 | 108,255 | 51,944,397 |

| 1960 | 42,838,639 | 20,706,431 | 6,116,848 | - | 482,848 | -6 | 46,604 | 70,191,370 |

| 1980 | 64,540,467 | 46,233,531 | 7,046,906 | - | 672,251 | - | 517,897 | 119,011,052 |

| 1991[26] | 75,704,927 | 62,316,064 | 7,335,136 | - | 630,656 | 294,135 | 534,878 | 146,815,796 |

| 2000[27] | 91,298,042 | 65,318,092 | 10,554,336 | - | 761,583 | 734,127 | 1,206,675 | 169,872,856 |

| 2010[28] | 91,051,646 | 82,277,333 | 14,517,961 | - | 2,084,288 | 817,963 | 6,608 | 190,755,799 |

| Race or Color | Brancos ("whites") | Pardos ("mixed") | Pretos ("blacks") | Caboclos ("indigenous"/"mestizo") | Amarelos ("yellow"/"Asian") | Indigenous | Undeclared | Total |

| 1872 | 38.14% | 38.28% | 19.68% | 3.90% | - | - | - | 100% |

| 1890 | 43.97% | 32.36% | 14.63% | 9.04% | - | - | - | 100% |

| 1940 | 63.47% | 21.21% | 14.64% | - | 0.59% | - | 0.10% | 100% |

| 1950 | 61.66% | 26.54% | 10.96% | - | 0.63% | - | 0.21% | 100% |

| 1960 | 61.03% | 29.50% | 8.71% | - | 0.69% | - | 0.07% | 100% |

| 1980 | 54.23% | 38.85% | 5.92% | - | 0.56% | - | 0.44% | 100% |

| 1991 | 51.56% | 42.45% | 5.00% | - | 0.43% | 0.20% | 0.36% | 100% |

| 2000 | 53.74% | 38.45% | 6.21% | - | 0.45% | 0.43% | 0.71% | 100% |

| 2010 | 47.73% | 43.13% | 7.61% | - | 1.09% | 0.43% | 0.00% | 100% |

^1 The 1900, 1920, and 1970 censuses did not count people for "race".

^2 In the 1872 census, people were counted based on self-declaration, except for slaves, who were classified by their owners.[29]

^3 The 1872 and 1890 censuses counted "caboclos" (White-Amerindian mixed race people) apart.[30] In the 1890 census, the category "pardo" was replaced with "mestiço".[30] Figures for 1890 are available at the IBGE site.[31]

^4 In the 1940 census, people were asked for their "color or race"; if the answer was not "White", "Black", or "Asians", interviewers were instructed to fill the "color or race" box with a slash. These slashes were later totaled in the category "pardo". In practice this means answers such as "pardo", "moreno", "mulato", "caboclo", etc.[32]

^5 In the 1950 census, the category "pardo" was included on its own. Amerindians were counted as "pardos".[33]

^6 The 1960 census adopted a similar system, again explicitly including Amerindians as "pardos".[34]

Important or famous Pardo Brazilians

Politics

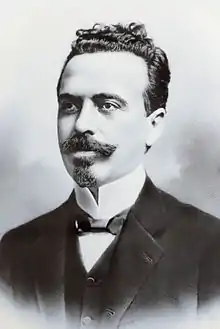

Pardos have made a minor impact in the Brazilian political arena which is largely dominated by whites.[35] Nilo Peçanha was disputably the only mulatto president of Brazil.[36][37] Another president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, also had some African ancestry and described himself as "slightly mulatto". He allegedly once said that he had "a foot in the kitchen" (a nod to 19th century Brazilian domestic slavery).[38][39]

Since the end of the military dictatorship, the political participation of pardos has increased. Senator and presidential candidate Marina Silva is a descendant of Portuguese and black African ancestors in both her maternal and paternal lines.[40]

Arts and entertainment

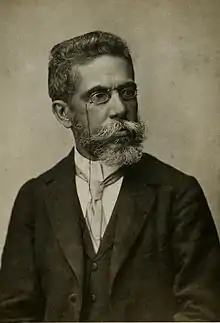

Many important names of Brazilian literature are or have been pardos. Machado de Assis, generally considered the most important Brazilian writer of fiction, was himself "pardo". Other remarkable writers include Lima Barreto (a novelist, master of satire and sarcasm, and pioneer of social criticism);[41] João Ubaldo Ribeiro (a novelist and short story writer); João do Rio (a journalist); and Paulo Leminski (a poet).

Other remarkable artists include Father José Maurício Nunes Garcia[42] (a baroque conductor and composer),and Aleijadinho (an outstanding sculptor and architect)[43] attained high prestige as artists.

It is in popular music, however, that the talents of pardos (along with Afro Brazilians, an even more disenfranchised group) found the most fertile ground for their development. Some of the examples include Chiquinha Gonzaga and Lupicínio Rodrigues [44]

Another field where "pardos" have excelled is soccer: Ronaldo, popularly dubbed "the phenomenon", is considered by experts and fans to be one of the greatest soccer players of all time.,[45][46][47] Arthur Friedenreich, Ademir da Guia, Romário are well known names in Brazilian soccer.

Important athletes in other sports include Daiane dos Santos[48] (gymnastics), known for the invention of original movements, Alex Garcia (basketball), who played in the NBA, etc.

Moreno

In daily usage, Brazilians use the ambiguous[65] term moreno, a word that means "dark-skinned", "dark-haired", "tawny", "swarthy", "Brown" (when referring to people), "suntanned".[66] Moreno is often used as an intermediate color category, similar to pardo, but its meaning is significantly broader, including people who self identify as black, white, Asian and Amerindian in the IBGE classification system.[67] In a 1995 survey, 32% of the population self-identified as "moreno", with a further 6% self-identifying as "moreno claro" ("light brown"), and 7% self-identified as "pardo". Telles describes both classifications as "biologically invalid", but sociologically significant.[25]

Demographics

By region

The Brazilian regions by percent of pardo people.

2009 data:[68]

- 1) North – 71.2% of pardos

- 2) Northeast – 62.7%

- 3) Central-West – 50.6%

- 4) Southeast – 34.6%

- 5) South – 17.3%

By state

According to IBGE's data for 2009,[68] of the ten states with greatest percentual pardo population, five were in the North and five in the Northeast.

- 1) Amazonas – 77.2%

- 2) Pará – 72.6%

- 3) Piauí – 69.9%

- 4) Tocantins – 68.8%

- 5) Maranhão – 68.6%

- 6) Alagoas – 67.7%

- 7) Acre – 67.7%

- 8) Sergipe – 67.1%

- 9) Amapá – 66.9%

- 10) Ceará – 66.1%

Between 2000 and 2010, the states of Goiás, Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo, together with the Federal District moved to the group of majority nonwhite states, of which pardos are very likely to be the new majority if trends continue as they perform the greatest nonwhite group in all Brazilian states. The next to be minority-majority is probably Mato Grosso do Sul (51.78% white), followed by Rio de Janeiro (54.25% white). The four southernmost states were all >70% white in the 20th century, nevertheless in the last 2010 census São Paulo turned to be almost exactly 70.0% white, and according to the contemporary demographic trends it is likely to be less than 70% now.

It should be pointed out that self-identification and ancestry don't correlate well in Brazil. A predominantly self identified "pardo" state like Goiás turned out to be mostly European in ancestry according to an autosomal study from the UnB undertaken in 2008. According to that study, the ancestral composition of Goiás is 83,70% European, 13,30% African and 3,0% Native American.[69]

In Fortaleza, for example, both "whites" and "pardos" displayed a similar ancestral composition, according to a 2011 autosomal study: a predominant degree of European ancestry (>70%) was found out, with minor but important African and Native American contributions.[15]

By municipality

IBGE's data for 2000.[70] Of the ten municipalities with the greatest percentual pardo population, eight were in the Northeast and two in the North.

- 1) Nossa Senhora das Dores (Sergipe) – 98.16% of pardos

- 2) Santo Inácio do Piauí (Piauí) – 96.90%

- 3) Boa Vista do Ramos (Amazonas) – 92.40%

- 4) Belágua (Maranhão) – 90.85%

- 5) Itacuruba (Pernambuco) – 90.05%

- 6) Monte Alegre de Sergipe (Sergipe) – 90.03%

- 7) Pracuuba (Amapá) – 89.99%

- 8) Ipubi (Pernambuco) – 89.93%

- 9) Floresta do Piauí (Piauí) – 89.37%

- 10) Pinhão (Sergipe) – 87.51%

References

- "Censo Demográfi co 2010 Características da população e dos domicílios Resultados do universo" (PDF). 8 November 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2014.

- (in Portuguese) Study Panorama of religions. Fundação Getúlio Vargas, 2003.

- Gentios Brasílicos: Índios Coloniais em Minas Gerais Setecentista. Tese de Doutorado em História, IFCH-Unicamp, 2003, 401p

- MAGNOLI, Demétrio. Uma Gota de Sangue, Editora Contexto 2008 (2008)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-13. Retrieved 2014-09-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Diogo de Vasconcelos, History of Minas Gerais, volume 1, testament of the Colonel Salvador Furtado Fernandes de Mendonça, from about 1725

- Gentios Brasílicos: Índios Coloniais em Minas Gerais Setecentista. Tese de Doutorado em História, IFCH-Unicamp, 2003, 401p; http://www.bibliotecadigital.unicamp.br/document/?code=vtls000295347 Archived 2014-09-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Nazzari, Muriel (1 January 2001). "Vanishing Indians: The Social Construction of Race in Colonial Sao Paulo". The Americas. 57 (4): 497–524. doi:10.1353/tam.2001.0040. PMID 19522106. S2CID 38602651.

- Dav(id I. Kertzer and Dominique Arel (2002). Census and Identity: The Politics of Race, Ethnicity, and Language in National Censuses. Cambridge University Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-521-00427-5.

- Do pensamento racial ao pensamento racional Archived 2014-05-22 at the Wayback Machine, laboratoriogene.com.br.

- "Folha Online - Ciência - DNA de brasileiro é 80% europeu, indica estudo - 05/10/2009". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Lins, T. C.; Vieira, R. G.; Abreu, B. S.; Grattapaglia, D.; Pereira, R. W. (March–April 2009). "Genetic composition of Brazilian population samples based on a set of twenty-eight ancestry informative SNPs". American Journal of Human Biology. 22 (2): 187–192. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20976. PMID 19639555. S2CID 205301927.

- http://www.unl.edu/rhames/courses/current/readings/santos-race-brazil.pdf

- Editor. "Negros e pardos do Rio têm mais genes europeus do que imaginam, segundo estudo". Meio News RJ. Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2015.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Pena, Sérgio D. J.; Di Pietro, Giuliano; Fuchshuber-Moraes, Mateus; Genro, Julia Pasqualini; Hutz, Mara H.; Kehdy, Fernanda de Souza Gomes; Kohlrausch, Fabiana; Magno, Luiz Alexandre Viana; Montenegro, Raquel Carvalho; Moraes, Manoel Odorico; de Moraes, Maria Elisabete Amaral; de Moraes, Milene Raiol; Ojopi, Élida B.; Perini, Jamila A.; Racciopi, Clarice; Ribeiro-dos-Santos, Ândrea Kely Campos; Rios-Santos, Fabrício; Romano-Silva, Marco A.; Sortica, Vinicius A.; Suarez-Kurtz, Guilherme (2011). Harpending, Henry (ed.). "The Genomic Ancestry of Individuals from Different Geographical Regions of Brazil is More Uniform Than Expected". PLoS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617063P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226.

- "Profile of the Brazilian blood donor". Archived from the original on 2 May 2012. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Freyre, Gilberto. Casa-Grande e Senzala, Edition. 51, 2006.

- "UFCG - UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE CAMPINA GRANDE-PB". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Pena, S.D.J.; Bastos-Rodrigues, L.; Pimenta, J.R.; Bydlowski, S.P. (2009). "Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research - DNA tests probe the genomic ancestry of Brazilians". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 42 (10): 870–876. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2009005000026. PMID 19738982.

- RIBEIRO, Darcy. O Povo Brasileiro, Companhia de Bolso, fourth reprint, 2008 (2008).

- Carvalho-Silva DR, Santos FR, Rocha J, Pena SD (2001). "The Phylogeography of Brazilian Y-Chromosome Lineages". Am J Hum Genet. 68 (1): 281–86. doi:10.1086/316931. PMC 1234928. PMID 11090340.

- Desenvolvimento: Ronnan del Rey. "Laboratório GENE - Núcleo de Genética Médica". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Saloum de Neves Manta F, et al. (2013). "Revisiting the genetic ancestry of Brazilians using autosomal AIM-Indels". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e75145. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875145S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075145. PMC 3779230. PMID 24073242.

- Rodrigues de Moura R, Coelho AV, de Queiroz Balbino V, Crovella S, Brandão LA (2015). "Meta-analysis of Brazilian genetic admixture and comparison with other Latin America countries". American Journal of Human Biology. 27 (5): 674–80. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22714. PMID 25820814. S2CID 25051722.

- Edward Eric Telles (2004). "Racial Classification". Race in Another America: the significance of skin color in Brazil. Princeton University Press. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-0-691-11866-6.

- Environmental Justice and Sustainable Development. With a case study in Brazil's Amazon using Q Methodology. Götz Kaufmann. p. 204 – via Google Books.

- "Tabela 7 - População residente, por cor ou raça, segundo as Grandes Regiões e as Unidades da Federação - 2000" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-12-16.

- "Tabela 1.3.1 - População residente, por cor ou raça, segundo o sexo e os grupos de idade" (PDF). 2010.

- Tereza Cristina N. Araújo. A classificação de "cor" nas pesquisas do IBGE.. In Cadernos de Pesquisa 63, November 1987. p. 14.

- Tereza Cristina N. Araújo. A classificação de "cor" nas pesquisas do IBGE. In Cadernos de Pesquisa 63, November 1987. p. 14.

- Diretoria Geral de Estatística. Sexo, raça e estado civil, nacionalidade, filiação culto e analphabetismo da população recenseada em 31 de dezembro de 1890. p. 5.

- IBGE. Censo Demográfico 1940. p. xxi.

- IBGE. Censo Demográfico. p. XVIII

- IBGE. Censo Demográfico de 1960. Série Nacional, Vol. I, p. XIII

- "DEMOCRACY: The Puzzling Whiteness of Brazilian Politics". Center for Latin American Studies (CLAS). 2013-07-23. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- BEATTIE, Peter M. The Tribute of Blood: Army, Honor, Race, and Nation in Brazil, 1864–1945. Duke University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8223-2743-0, ISBN 978-0-8223-2743-1. pp. 7. (visited 3 September 2008)

- GIFFIN, Donald W. The Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 44, No. 3 (Aug., 1964), pp. 437–439. Review of TINOCO, Brígido. A vida de Nilo Peçanha. Coleção Documentos Brasileiros, Livraria José Olympio Editora, RJ, 1962. (visited 3 September 2008)

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld - Chronology for Afro-Brazilians in Brazil". Refworld. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- "Banco de Dados Folha - Acervo de Jornais". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Marina Silva deixa o PT (in Portuguese)

- br/lima_barreto-biografia.html "Lima Barreto: Um escritor de triste fim" Check

|url=value (help). Escritores.folha.com.br. 1970-01-01. Retrieved May 13, 2020. - Ricardo Bernardes. José Maurício Nunes Garcia e a Real Capela de D. João VI no Rio de Janeiro Archived 2012-04-05 at the Wayback Machine. p. 42.

- Domingos Tavares. Sensibilidade e cultura na obra arquitectónica do Aleijadinho. p. 120.

- Gilberto Ferreira da Silva et alli. RS negro: cartografias sobre a produção do conhecimento p. 111.

- "Ronaldo: In his pomp, he was a footballing force close to unstoppable". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 August 2014

- "Zidane talks about Ronaldo". CNN Interview. Retrieved 3 August 2014

- "Ronaldo, a phenomenon in every sense". FIFA.com. Retrieved 13 May 2013

- Nei Lopes. Enciclopédia brasileira da diáspora africana. p. 603.

- http://mulher.pt.msn.com/juliana-paes-a-musa-brasileira Archived 2014-07-28 at the Wayback Machine |título=Juliana Paes, a musa brasileira |editor=MSN |citação=A sua família tem descendência árabe, negra e indígena. |data=15 de dezembro de 2012 |acessodata=19 de julho de 2014

- "Fernando Henrique Cardoso - Governo e Biografia - Famosos". Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- "Débora Nascimento é nossa primeira capa de 2013. "Sou desse jeito, mulherão. Tenho bundão, bocão, pernão"". 25 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- "Brasil - NOTÍCIAS - Marina Silva deixa o PT". Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Costa, Antonio Luiz M. C. "Voto em Marina não é ecológico, mas também não evangélico". Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2015-07-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-07-27. Retrieved 2015-07-07.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ContentStuff.com. "Raça Brasil - DEBATE: SER NEGRO É UMA QUESTÃO DA COR DA PELE? - Confira as opiniões!". Archived from the original on 27 July 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- "Machado de Assis 'branqueado' - Revista de História". Archived from the original on 5 August 2014. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- "Machado de Assis - Companhia das Letras". Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- "Mestiço, pobre, nevropata: biografia e modernidade no Machado de Assis de Lúcia Miguel Pereira. - Anais Anpuh". Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- ContentStuff.com. "Raça Brasil - COM VOCÊS, VANESSA DA MATA - A cantora mato-grossense colhe os frutos de tocar em trilhas de novelas e reluta entre fama e anonimato". Archived from the original on 14 April 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Beattie, Peter M. (2001-09-26). The Tribute of Blood: Army, Honor, Race, and Nation in Brazil, 1864–1945. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2743-1.

- "(...) which made him very proud of having the blood of the three races that formed the Brazilian people: white, indigenous and black (portuguese)" (PDF).

- "À Flor das Águas: a imagem do Recife em Josué de Castro" (PDF).

- "Márvio dos Anjos » "Neymar não se acha negro": canalhice ou desinformação? » Arquivo". Retrieved 27 June 2016.

- Edward Telles. Race in another America: the significance of skin color in Brazil. p. 82: "Ethnographers have found the term ambiguous enough to substitute for almost any other color category."

- "moreno - English translation - bab.la Portuguese-English dictionary". Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- Edward Telles. Race in another America: the significance of skin color in Brazil. p. 87.

- "Síntese dos Indicadores Sociais 2010" (PDF). Tabela 8.1 - População total e respectiva distribuição percentual, por cor ou raça, segundo as Grandes Regiões, Unidades da Federação e Regiões Metropolitanas - 2009. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística (IBGE). 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-05.

- "Untitled Document" (PDF). Archived from the original on 6 July 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

- "Sistema IBGE de Recuperação Automática - SIDRA". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 May 2015.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)