Brazilians

Brazilians (Portuguese: Brasileiros, IPA: [bɾaziˈlejɾus])[26] are citizens of Brazil. A Brazilian can also be a person born abroad to a Brazilian parent or legal guardian as well as a persons who acquired Brazilian citizenship. Brazil is a multiethnic society, which means that it is home to people of many ethnic origins. As a result, a majority of Brazilians do not identify their nationality as not being necessarily directly related to their ethnicity; in fact, the idea of ethnicity as it is understood in the anglophone world is not popular in the country.

In the period after the colonization of the Brazilian territory by Portugal, during much of the 16th century, the word "Brazilian" was given to the Portuguese merchants of Brazilwood, designating exclusively the name of such profession, since the inhabitants of the land were, in most of them, indigenous or Portuguese born in Portugal or in the territory now called Brazil.[27] However, long before the independence of Brazil, in 1822, both in Brazil and in Portugal, it was already common to attribute the Brazilian gentile to a person, usually of clear Portuguese descent, resident or whose family resided in the State of Brazil (1530–1815), belonging to the Portuguese Empire. During the lifetime of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves (1815–1822), however, there was confusion about the nomenclature.

Definition

According to the Constitution of Brazil, a Brazilian citizen is:

- Anyone born in Brazil, even if to foreign born parents. However, if the foreign parents were at the service of a foreign State (such as foreign diplomats), the child is not Brazilian;

- Anyone born abroad to a Brazilian father or a Brazilian mother, with registration of birth in a Brazilian Embassy or Consulate. Also, a person born abroad to a Brazilian father or a Brazilian mother who was not registered but who, after turning 18 years old, went to live in Brazil;[28]

- A foreigner living in Brazil who applied for and was accepted as a Brazilian citizen.

According to the Constitution, all people who hold Brazilian citizenship are equal, regardless of race, ethnicity, gender or religion.

A foreigner can apply for Brazilian citizenship after living for four uninterrupted years in Brazil and being able to speak Portuguese. A native person from an official Portuguese language country (Portugal, Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, São Tomé and Príncipe, Guinea Bissau and East Timor) can request the Brazilian nationality after only 1 uninterrupted year living in Brazil. A foreign born person who holds Brazilian citizenship has exactly the same rights and duties of the Brazilian citizen by birth, but cannot occupy some special public positions such as the Presidency of the Republic, Vice-presidency of the Republic, Minister (Secretary) of Defense, Presidency (Speaker) of the Senate, Presidency (Speaker) of the House of Representatives, Officer of the Armed Forces and Diplomat.[28] The population in Brazil is over 204,519,000.

History and overview

Brazilians are mostly descendants of Portuguese settlers, post-colonial immigrant groups, enslaved Africans and Brazil's indigenous peoples. The main historic waves of immigration to Brazil have occurred from the 1820s well into the 1970s, most of the settlers were Portuguese, Italians, Germans, and Spaniards, with significant minorities of Japanese, Dutch, Armenians, Romani, Greeks, Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, and Levantine Arabs.[29]

The colonization period (1500 to 1822)

The three principal groups were Native Brazilians, European colonizers and African labor.

- Brazil was inhabited by an estimated 2.4 million Amerindians before the first settlers arrived in the 16th century. They had been living there since the Pleistocene and still exist in many tribes and ethnicities, amounting to the hundreds, giving them varying features, shapes and shades. There are different estimates for the Indigenous population around 1498, when the cohort commanded by Duarte Pacheco Pereira first set foot in Brazilian territory, followed by Pedro Álvares Cabral and Amerigo Vespucci in 1500 and 1502, with figures revolving between 2.4 million and 3.1 million. What is more accurate is that about three quarters of them died from contracted diseases brought by colonizers (the flu, smallpox, measles, scarlet fever and tuberculosis) and conflicts (besides the numerous deaths in different tribal groups by forging alliances with the Portuguese, French and Dutch to fight each other, ending in genocide, the abortion rate also increased among Indigenous women after the arrival of the colonizers), while the remaining were pushed to the Amazon Basin, sometimes migrating beyond the borders with Hispanic provinces. It is also important to mention that a strong assimilation by miscegenation with local populations occurred, where Natives living under Jesuit protection and having a monastic life decided to leave for the life in towns. The European diseases spread quickly along the indigenous trade routes, and whole tribes were likely annihilated without ever coming in direct contact with Europeans. Today, 517,000 Indigenous people live in reservations and 160 thousand speak assorted Native languages, whereas millions of Brazilians have at least some degree of Amerindian ancestry due to the mentioned interracial encounters.

- The country was officially discovered by Portugal in 1500 and received about 724,000 Portuguese colonizers, mostly males, who settled there until the end of Colonial Brazil.[30] But other sources even claim that the given numbers of total entrances were clearly surpassed. The Jesuits asked the Portuguese Crown to ship orphaned women under royal wardship for marriage with the settlers; they were known as Órfãs d'El-Rei (modern órfãs do rei, "orphans of the king").[31][32][33][34] Daughters of noblemen who died overseas administrating captaincies in the colonies or in battle for the king would marry settlers of higher rank. Bahia's port in the Northeast received one of the first groups of orphans in 1551.[32]

Portugal remained the only significant, but not an exclusive source of European immigration to Brazil until the early 19th century.

- These other people came from different nationalities - but the by far most mentioned are the Dutch. Hence, under the rule of Dutch Brazil in the northeastern part of the country, from 1630 to 1654, a comparatively small but still notable number of Dutch settlers (Dutch Brazilian) and some Jewish People arrived, the latter seeking religious freedom. These Jews founded the first Synagogue in the Americas, named Kahal Zur Israel Synagogue in the city of Recife.

It is estimated that more than 20,000 Dutch entered Brazil, however, both groups had been forced out of the country after the rule's end. The remaining families mostly fled to remote parts of the interior of Northeastern Brazil (mainly in the states of Pernambuco, but also Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará and others) or changed their names to Portuguese ones. The proven excess of Y-chromosomes of the haplogroup 2 in northeasterners probably results from the high miscegenation of Dutch settlers with the local population.

The Jews who mostly left Brazil took off to what was then named New Amsterdam, today New York City, and founded the oldest Jewish congregation in the United States, the Congregation Shearith Israel. The ones who stayed, converted into Christianity and were then known as New Christians or Marranos, who sometimes practiced Crypto-Judaism. Even if the Jewish population under Dutch Brazil not surpassed a few thousand individuals, a considerably higher number of New Christians, in the past simply absorbed as Portuguese colonizers, arrived in Colonial Brazil - especially in the first centuries after 1500. They entered Brazil fleeing from the Inquisition or were deported by the Kingdom of Portugal and also Spain, latter being known as Degredados, someone who was sentenced or forced to exile. This also included Romani People from the Iberian Peninsula, what partially explains the curiously high numbers for a western country. Brazil has the second largest Gypsy population in the Americas after the United States, having also received Roma people from Central and Eastern Europe, as well as the Baltic countries during the 20th century.

- As a result of the Atlantic slave trade from the mid-16th century until 1855, an estimated 3.6 million African people, also from many countries and ethnicities were brought to Brazil, giving the country the Americas' largest population with some African ancestry. Many of the slaves suffered under severe conditions and the mortality rates were pretty high, what led to the foundation of Quilombola communities throughout the country. A small number of the slaves in the state of Bahia were actually Muslims; they produced a revolt in the city of Salvador that was quickly tamed by the army.

In 1808, the Portuguese court moved to Brazil, bringing thousands of Portuguese again and afterwards opened its seaports to other nations starting from 1820. This caused the biggest wave of immigration which the country has seen until then.

The Great Immigration (1820 until the 1970s)

In this period, people from all over the world officially entered Brazil, the vast majority of them Europeans.

Between 1820 and the 1950s, Brazil received around 5,686,133 European immigrants, including a thriving Jewish population.[35][36] In addition, 950,000 Asians settled in Brazil throughout the 20th century, including considerable numbers of Middle Easterners or Christian Levantine Arabs and 270,000 Japanese, the highest figure among East Asians.[37][38][39][40][41]

- Back then, nearly 70 % of those immigrants originated from Southern Europe.

- A second wave of Portuguese people arrived (here: Postcolonialism), this time with more than 1,8 million immigrants.

Portuguese people have been present since the discovery of the country, and therefore it is difficult to estimate a more accurate number of descendants. Millions of White Brazilians descend from recent Portuguese immigration from between the 1870s and 1975. In addition, many multiracial Brazilians partially descend from Portuguese people, caused by the high intermarriage rates. Most of them came from the historical provinces of Minho, Trás-os-Montes, Beira, Estremadura (North and Central Portugal). Northeastern Brazil traditionally received the first waves of immigrants, but during the Great Immigration, the Southeast received the biggest influx. São Paulo (state) received the most, followed by Rio de Janeiro (city), which is considered the largest Portuguese city outside of Lisbon. The second former capital of Brazil once also was the capital of Portugal, the only European capital outside of Europe. The accent in the city of Rio de Janeiro subsequently reminds the 19th century innovations that took place in the European variety of the language, while the prosody of the rest of the country, besides some local varieties, has rather conservative phonetics rooted in the 1600s. Other states with significant numbers were Minas Gerais, Pará, Rio Grande do Sul, Pernambuco and Bahia. Nowadays, they naturally live throughout Brazil and compose the majority of White and also Multiracial Brazilians in many states.

- Furthermore, around 1.6 million Italians were responsible for a massive immigration wave, consequently composing the biggest European follow-up group the country has received after its colonizers.

Today, millions of Italian-Brazilians make Brazil their home, as they usually brought the whole family and had high birth rates. Regarding the total numbers, this probably represents the biggest Italian diaspora outside of Italy. Contrary to other countries, more than half of the Italians immigrated from the North, mostly composed by people from Veneto and Lombardy, followed by people from Central Italy. The state of São Paulo had the strongest and a more diverse influx, with many also coming from South Italy, especially to the eponymic capital. Italians mostly went to São Paulo (state), which received half of the overall immigrants. The others mainly went to the states of southern Brazil, where they also composed the biggest European immigrant group. Other notable influxes occurred in two other southeastern states, here Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo and the Central-West region, mainly to Mato Grosso do Sul and Goiás. Comparatively small numbers went to Pernambuco and Bahia, both in the Northeast. Nowadays the descendants mostly live in mentioned areas, but the sheer amount and internal migrations made the Italilan diaspora spread out and nowadays they are scattered all over Brazil.

- Spaniards also arrived in rather high numbers, with around 700,000 immigrants mainly from Andalusia and Galicia.

Several million Brazilians have Spanish ancestry. Most Spaniards settled in the past century, where they chiefly headed to São Paulo, then Rio de Janeiro and Minas Gerais. Most notably from Andalusia (South), others from the provinces of Galicia, Castile and León and Catalonia (North and East Spain) followed. Galicians were also present throughout Colonial Brazil, as the province shares borders and linguistic ties with Portugal, and once was part of the country. Spanish Brazilians in the other states mainly have origins in Galicia, which arrived in earlier occasions. Many of them went to the first capital Salvador and its state Bahia, but also Pernambuco (Northeast), Pará (North), Espírito Santo (Southeast), and Rio Grande do Sul (South).[42]

Note: Brazil is also home to other Southern European populations, mainly Greeks (around 150,000 descendants), but they are by far the smallest groups with origins in South Europe.

2) The remaining 30 % were composed of Other Europeans, Asians (Western and Eastern Asia), Africans (many White Africans, Jews, Berbers and others) and Americans (South and North Americans).

- Other Europeans:

- Western Europeans were very present, as around 240,000 Germans settled, 198,000 Austrian and 52,000 Swiss; Luxembourgers and Volga Germans were also documented, but in comparatively low numbers. German speaking nationalities were the fourth largest European immigration group and today German is the second most spoken mother tongue in the country.[43][44][45][46] In addition, 150,000 French immigrants entered Brazilian ports, where Belgian and Dutch[47][48] (not to be confused with Dutch Brazil) settlers also were listed.

- Eastern Europeans were relatively numerous, with more than 350,000 listed immigrants. This included 154,000 Poles, around 40,000 Ukrainians and smaller numbers of Russians. These immigrants were searching for better opportunities - a few thousand Belarusians were also among them.[49][50][51][17] Slavs from other regions migrated as well, here mainly South Slavs like Bulgarians and Croats, but also Czechs and Slovaks, with moderate numbers of Slovenes and others.[15][52][53] Hungarians[54][55] and Romanians were among the non-Slavic Eastern Europeans and were the biggest groups after the Poles, Russians and Ukrainians.

- Northern Europeans were the least numerous, but also present. More than 78,000 Britons, mainly under English passports, and Scots entered the country. They dispersed to different regions: a few Irish people went to already urbanized regions.[19][20][56] Scandinavian people, mainly Swedes and Norwegians, were both listed and sent over 40,000 immigrants each, as well as around 17,000 Danes. 3,400 Estonians[58] and a rather small number of Finns were also present. Even smaller and therefore often forgotten, an influx from Icelanders and Faroese was recorded, but they still left few thousand descendants.[53] The Baltic region was also entirely present, where Lithuanians composed the most numerous group, with over 50,000 entrances, followed by a much smaller number of Latvians.[53][59][60]

- European Jews of Ashkenazi origin, more precisely around 48,000 people from several countries, chose Brazil as their destination. Ashkenazi Jews were first documented during Imperial times, when the liberal second emperor of Brazil welcomed a few thousands of families facing persecution in Europe during the 1870s and 1880s.[61] Two heavier influxes took place during the 20th century. The earliest right after the Great War and the second inrush between the 1930s and 1950s.[49][61] Brazil has also seen an influx from North African Jews of Sephardic origin coming from mainly Morocco and Egypt, which were counted extra.

- Asians:

- Western Asians, more specifically from the Levant region, equally arrived in large numbers, chiefly Lebanese and Syrians, both surpassing 200,000 entrances throughout the 20th century,[62][63] with mentionable numbers of Armenian, Georgian and some Iranian immigrants from the Caucasus region.

- East Asians, the majority composed of Japanese immigrants, also arrived in formidable numbers, where the first ship landed in 1908, surpassing 250,000 immigrants.[39][64][65][66][67] But Chinese and Koreans also have traditions of immigrating to Brazil, especially after the 1950s, with around 50,000 and 20,000 immigrants respectively.

- Pan-Americans:

- North Americans also formed the melting pot that is Brazil, with the country being one of the few which received Americans who fled the American Civil War, settling in Southeastern and Southern Brazil during the American reconstruction period. In addition, smaller numbers of North Americans immigrated after 1808.[21][22][23] The descendants of those Confederate colonies are culturally known as the Confederados sub-group, especially in the countryside of São Paulo, where they founded towns and their presence was stronger[21] - Brazilians of American descent can be found throughout the country, resulting from other periods and the dispersion of the Confederados descendants, who are nowadays mostly mixed with other groups and sometimes mistaken for descendants of British immigrants. Ethnically the Confederados were mostly English-Welsh, Scottish, Irish, German and Scandinavian.[68]

- South Americans were strongly represented by Argentines since the 18th century and always had a strong community in the country. They still form one of the largest South American immigrant groups in Brazil, nowadays only surpassed by Bolivians (see modern times). Uruguayan citizens after the country's independence from the Empire of Brazil were also noticeable throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

- Africans:

- North African regions, historically distinguished from Sub-Saharan Africa, also sent immigrants. This time they mainly came from Egypt, with around 10,000 people, than the Maghreb region, especially Morocco (mostly Jews who went to Northern Brazil). Therefore, a stronger influx from other cultures occurred, contrary to Colonial Brazil, where most Africans were forced labor work brought from the Black populations.

- Other Africa-born people mainly include Dutch South Africans (Boeren or Afrikaners) and people from the former Portuguese Empire, mainly Angola (during the Great Immigration, but especially after the Civil Wars post-independence). Here people of several ethnicities immigrated (mainly Africans of European descent, but also Blacks and Coloured people).

Note: Dozen other immigrant groups form sizable communities with some varying number of descendants (5,000 to + 30 million). Only in this period, the port of Santos, São Paulo, which was widely known as the most important entrance of immigrants in Brazil, received people from more than 60 countries. Other important ports, which occasionally received other immigrant groups as the before mentioned, were the ones in the cities of Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Vitória, Recife etc.[29]

Modern times (1970 to now)

Not to be compared with the great immigration before, a still ongoing influx from Africa (Angola, Senegal) and South America and the Caribbean (Bolivia, Paraguay, Chile, Uruguay, Haiti, Suriname, Jamaica, Barbados) is happening since the late 1960s. Asian immigrants (from Palestine, China, South Korea, returning Japanese Brazilians, Dutch Indonesians, Afghans and immigrants from Vietnam, Iran, Pakistan, the Philippines and others) as well as European immigrants (Portugal due to ties, young qualified professionals from Western Europe, especially after 2008, Northern Europeans who seek warmer weather and several Eastern Europeans) are thriving in varying numbers.

After 1975 large groups of Dutch Surinamese or Boeroes immigrated to Brazil due to the independence in Suriname. Most of them settled in the countryside of São Paulo and Paraná where there are thriving Dutch Brazilian colonies.

Current foreign population

In 2011, the country was home to 1.5 million foreign born people, more than twice as of 2009.

These numbers could be higher, as there are many undocumented people in Brazil as well. For both documented and undocumented migrants, most of the foreigners come from Portugal, Bolivia, China, Paraguay, Angola, Spain, Argentina, Japan and the United States.[69] The major work visas concessions were granted for citizens of the United States and the United Kingdom in 2009.[70]

Lusitanian immigration never ceased throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Portuguese people in diaspora settled in Brazil especially during the 1970s coming from former Portuguese colonies like Macau or Angola after its independence. An additional figure of 1.2 million Portuguese arrived between 1951 and 1975 to settle mostly in the Southeast.[71] Nowadays, Lusitanians constitute the biggest group of foreigners living in the country, with over 690,000 Portuguese nationals currently living in Brazil.[72] The vast majority arrived in the last decade. The first semester of 2011 solely had an increase of 52 thousand Portuguese nationals applying for a permanent residence visa while another large group was granted Brazilian citizenship.[73][74]

Today, people of more than 220 nationalities have communities in Brazil, 40 of them more than 10,000 people.

Refugees

In 2014, Brazil was home to 5,208 refugees from 79 nationalities. The three largest refugee ancestries were Syrian (1,626), Colombian (1,154) and Angolan (1062). In addition to these numbers, there are several thousand people who had entered the country and are still waiting for the government to acknowledge their refugee status, as 1,830 people from Bangladesh[75] in 2013 alone and other 1,021 people from Syria and 799 people from Senegal, for example.[75]

Brazil is today home to 4.5 thousand Afghans and was a destination for Vietnamese boat people in the past.

Dispersal of races and colours in the country

Note: The ethnic composition of Brazilians is not uniform across the country.

Although most Brazilians identify as white, mixed or black, genetic studies shows that the overwhelming majority of the citizens are actually triracial at some degree[76][77]

- Due to its large influx of European immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries, São Paulo, and the Southern Region have a White majority (mostly Europeans of Italian, Portuguese, German, Austrian, Swiss, Slavic, Dutch and Spanish ancestry).[78][79] Rio de Janeiro has a sizable white population slightly over 50% of the total population.[80]

The other two Southeastern states, Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo,[81] are around 50% White (the Southeast region also includes Levantine Arabs).[78] São Paulo has the largest absolute number with 30 million Whites, followed by Minas Gerais, Rio Grande do Sul, Rio de Janeiro and Paraná, while Santa Catarina, where 86% of the population has European phenotype, reaches the highest percentage.[78]

The cities of São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Porto Alegre, Curitiba, Brasília and Belo Horizonte have the largest populations of Ashkenazi Jews.[35]

Most East Asians, especially Japanese Brazilians, the largest group, live in São Paulo and Paraná.[66][82] Most Koreans also live in São Paulo whereas the Chinese diaspora is spread particularly throughout the Southeast. Rio de Janeiro has a large Chinese population following São Paulo.

- The Northeastern Region, the first occupied and therefore most mixed region, has larger numbers of people with darker features, with stronger African, Romani, Amerindian and Sephardi influences from Colonial Brazil. The majority there is composed of Pardo (mixed) people, who are of a brownish or darker phenotype with light to dark features, followed by Whites (mostly Europeans and also with admixtures) and then by people with mostly African blood - Bahia and Maranhão have the biggest Black African populations in Brazil.[83] The individual appearance of Pardo people varies extremely, but generally all types and colours of hairs, eyes and skin are involved (usually not the extremes as extremely white or extremely black). But in fact, minorities in the White and Black populations consider themselves as Pardo. Moreover, some people in the Roma, Sephardic, Arab and Asian population classify themselves as Pardo, due to miscegenation with other races.

- Northern Brazil, largely covered by the Amazon Rainforest, is also mostly Pardo, due to a stronger Amerindian influence.[84]

- The two remaining South Eastern states and Central-Western Brazil have a more balanced ratio among racial groups (around 50% White, 43% Pardo, 5% Black, 1% Asian/Amerindian).

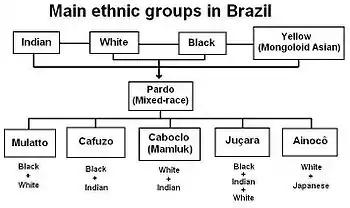

The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE) classifies the Brazilian population in five categories: brancos (white), negros (black), pardos (brown or mixed), amarelos (Asian/yellow) and índios (Amerindian), based on skin color or race. The last detailed census (PNAD) found Brazil to be made up of c. 91 million white people (White Brazilian), 79 million multiracial people (Pardo), 14 million black people (Afro-Brazilian), 2-4 million Asian people (Asian Brazilian) and 807,900 indigenous (Amerindian) people.

In the 2005 detailed census, for the first time in two decades, the number of White Brazilians did not exceed 50% of the population. On the other side, the number of pardos (multiracial) people increased and all the others remained almost the same. According to the IBGE, this trend is mainly because of the revaluation of the identity of historically discriminated ethnic groups.

Brazil is said to be among the most miscegenated countries in the world, as since the country was discovered and during the colonial period intermarriage between races was never illegal and common. Those of full ancestry are usually the Brazilians who can trace back their ethnicity to more recent immigration from the monarchical period in the 19th century until the Republican 20th and 21st centuries. Still, many Brazilians can not trace back their real origin easily. For instance, European family names which were difficult to pronounce were commonly changed to easier Portuguese surnames. In basic terms, it could be said that half of Brazilians are descendants of populations from the colonial era and the other half made of modern immigration. Brazil is a true melting pot of Europeans, Asians, Africans and Indigenous people, who either are in the single group or a mixture of various backgrounds and races.

| Skin color or race | % (rounded values) | |

|---|---|---|

| 2000[85] | 2008[86] | |

| White | 53.74% | 48.43% |

| Black | 6.21% | 6.84% |

| Mixed-race | 38.45% | 43.80% |

| East Asian | 0.45% | 1.1% |

| Amerindian | 0.43% | 0.28% |

| Not declared | 0.71% | 0.07% |

White Brazilians

Whites constitute the plurality of Brazil's population regarding the total numbers within a single racial group, having the most numerous population in the Southern Hemisphere. These are people who have origins in any of the white populations of Europe, North Africa and West Asia.[87]

The country has the second largest White population in the Americas, with around 91,051,646 people.[88]

And White Brazilians make up the third largest White population in the world, after the United States and Russia, also counting in total numbers.[88][89][90]

The majority of European Brazilians came from the Great Immigration period, which was the large European influx after steps had been taken for "whitening policies" during the Monarchy and Early Republican periods. Those policies also sought labor and also were made in order to avoid the foreign invasion threat of sparsely populated areas in the South. Various other groups derive from colonial times and post-war decades.

There are people of European descent distributed throughout the entire territory of Brazil, however, Southeast and South Brazil have the largest White populations. Whereas the Southeast region has the largest absolute numbers, 79.8% of the population in the three southernmost states has European or Caucasian phenotype. The state of Santa Catarina in Southern Brazil has the highest percentage, being almost 90% European. São Paulo in the Southeast has the fourth highest rate, but is the state with the most Whites in absolute numbers of 30 million Whites, mainly from Europe, also having largest Levantine Arab and Jewish populations.

| Some southern Brazilian towns with a notable main ancestry | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Town name | State | Main ancestry | Percentage |

| Nova Veneza | Santa Catarina | Italian | 95%[91] |

| Pomerode | Santa Catarina | German | 90%[92] |

| Prudentópolis | Paraná | Ukrainian | 70%[93] |

| Treze Tílias | Santa Catarina | Austrian | 60%[94] |

| Dom Feliciano | Rio Grande do Sul | Polish | 90%[95] |

Brazil is home to 240 immigrant or extoctone languages, most of them European languages. Standard German and German dialects make the second most spoken language in Brazil with around 4 million bilingual speakers or 2% of the population,[11][15][96][97][8][98] other Caucasoid immigration languages are Italian, Venetian or Talian dialect,[99] Polish,[13][14][15] Castilian, Ukrainian,[15] Russian,[17] Dutch,[15][8] Hebrew, Yidish,[15][100] Lithuanian and Lettish,[15][60] French,[15] Norwegian,[15] Swedish,[15] English,[19][21] [22][23][101] Hungarian,[15] Finnish,[15] Arabic, Danish,[15] Bulgarian, Croatian,[15] Catalan, Galician, Greek, Armenian, Czech,[15] Slovakian, Slovenian,[15] Romanian, Serbian, Vlax Romani,[15] Georgian, Turoyo and Baltic or Lithuanian Romani.[15]

Assorted German dialects (including the ancient East Pomeranian dialect, practically extinct in Europe)[102] and Venetian or Talian share co-official status with Portuguese in several municipalities.[103][104]

| Region | Percentage |

|---|---|

| North Brazil | 23.5% |

| Northeast Brazil | 28.8% |

| Central-West Brazil | 41.7% |

| Southeast Brazil | 56% |

| Southern Brazil | 78% |

Mixed (multiracial) people

Multiracials constitute the second largest group of Brazil, with around 84,7 million people. The term Pardo or mixed race Brazilian is a rather complex one. Multiracial Brazilians appear in hundreds of shades, colours and backgrounds. They are typically a mixture of colonial and post-colonial Europeans with descendants of African slaves and the Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Some individuals may also descend from Maghreb people, Jews, Middle Eastern and Egyptian people, or a more recent ancestry from East or South Asia. Skin colours can vary from light to dark. The caboclo or mestiço population, those who are a miscegenation of Native and European, revolves around 43 million people. Genetic studies conducted by the geneticist Sergio D.J. Pena of the Federal University of Minas Gerais have shown that the Caboclo population is made of individuals whose DNA ranges from 70% to 90% European (mostly Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch, French or Italian 1500s to 1700s male settlers) with the remaining percentage spanning different Indigenous markers. Similar DNA tests showed that people self-classified as Mulatto or White and Black mix, span from 62% to 85% European (mostly descendants of Portuguese, Dutch and French settlers during the colonial period in the Northeast). The Pardo category in Brazil also includes 800 thousand Gypsies or Roma people, most of them coming from Portugal but also countries in Eastern Europe and the Baltics. Eurasians can also be classified as Pardo. The majority of them consisting of Ainoko or Hafu, individuals who are a miscegenation between Japanese and European.

Recent research has suggested that Asians from the early Portuguese Eastern Empire, known as Luso-Asians first came to Brazil during the sixteenth century as seamen known as Lascars, or as servants, slaves and concubines accompanying the governors, merchants and clergy who has served in Portuguese Asia.[105] This first presence of Asians was limited to Northeast Brazil, especially Bahia, but others were brought as cultivators, textile workers and miners to Pará and other parts of the Northeast.

The largest populations with Pardo individuals are found in northern and northeastern Brazil, with many inhabiting the states of Mato Grosso, Goiás, Espírito Santo, Minas Gerais, Rio de Janeiro State, São Paulo State and Paraná State, as well as the Federal District. While the occurrence of Pardos is not uniform across the country, there are states with more people of mixed background than others. It also can happen that Pardos constitute significant numbers within single regions in states.

| Region | Percentage |

|---|---|

| North Brazil | 71.2% |

| Northeast Brazil | 62.7% |

| Central-West Brazil | 50.6% |

| Southeast Brazil | 35.69% |

| Southern Brazil | 17.3% |

Black Brazilians

Blacks constitute the third largest ethnic group of Brazil with around 14,5 million citizens or 7,6 % of the population. These are people who have origins in any of the black populations of Africa, although that is not exclusive to this group. In the country, these are generally used for Brazilians with at least partial Sub-Saharan African ancestry. Most Brazilians of African ancestry are the direct descendants of captive Africans who survived the slavery era within the boundaries of the present Brazil, but also with considerable European and Amerindian ancestry. Afro-Brazilians might not directly be compared to Pardo-Brazilians, as typically their skin colour is darker compared to mixed-race Brazilians, but these two populations are often counted together for statistical purposes and also when creating social policy in the country. Brazil, followed by the United States, has the largest African diaspora in the Americas.

Today most Blacks are either Catholic or Evangelical. Smaller groups are Irreligious including Atheists and a number of African traditional religions can be found especially in Bahia, notably Candomblé and Umbanda. The latter being a syncretism of Roman Catholicism, African traditions, Spiritism and Indigenous beliefs. A minority of Blacks follows Kardecism, which is a blend of Christianism and Spiritualism founded in France.

The black population is dispersed throughout the country, but it is a particularly important component of the demographics of northeastern states such as Bahia and coastal regions, such as the former capital of Rio de Janeiro.

| Region | Percentage |

|---|---|

| North Brazil | 6.2% |

| Northeast Brazil | 8.1% |

| Central-West Brazil | 5.7% |

| Southeast Brazil | 7.91% |

| Southern Brazil | 3.6% |

Asian Brazilians

Asians, in common parlance referred to East Asians, constitute the fourth largest ethnic group of Brazil with 2.2 million people. The largest group of East Asian ancestry in the country is the Japanese community. Brazil has the largest population of people of Japanese ancestry outside Japan, whether by percentage or absolute numbers. The number of Japanese Brazilians revolves around 1.8 million descendants and the Japanese community also comprises 57 thousand Japanese nationals.[64][65][66][67] According to Ethnologue over 400 thousand people speak Japanese in Brazil.

Other important immigrant groups have Chinese, Taiwanese and South Korean origins. Due to the recent immigration of Chinese citizens to Brazil that is currently the fastest growing population of Asian roots in the country.

South Asians also left descendants in Brazil, although more recently than East and West Asians. Currently, there is an influx of Bengalis, most of them refugees. There are no studies, however, over how South Asians are classified in the Brazilian typical racial system, and it is possible that South Asians arenot be included into the category "yellow" category of skin colour, which is usually used as a proxy to quantify the population of Asian ancestry (other than West Asian) in Brazil.

There are large groups of East Asian Catholics as well as non-religious Asians. Buddhism in Brazil is common amongst Asians and non-Asians, especially Whites, with Japanese Buddhism being the most usual and oldest form. Shinto practices involving life style and funerals are very common in Nipponese families of São Paulo and Paraná states. Shinto-derived Japanese New Religions are reasonably popular in the country, particularly in the South East, and may be practiced in syncretism with Christianity, Afro-Brazilian religions and Spiritism. The largest Nipponese new religions are Seicho-no-Ie, Tenrikyo, Perfect Liberty Kyodan and Church of World Messianity. Korean Confucianism and Chinese Confucianism are also found in the country, particularly in the city of São Paulo.

| Region | Percentage |

|---|---|

| North Brazil | 0.5 - 1% |

| Northeast Brazil | 0.3 - 0.5% |

| Central-West Brazil | 0.7 - 0.8% |

| Southeast Brazil | 1.1% |

| Southern Brazil | 0.5 - 0.7% |

Indigenous people

Indigenous people constitute the fifth largest ethnic group of Brazil, with around 800,000 individuals. This is the only category of the Brazilian "racial" classification that is not based on a skin color, but rather on cultural and ethnic belonging. It is the oldest ethnic group in the country, but nowadays its population is mainly located in the surroundings of the Amazon basin inside the Amazon Forest but also in various reservations throughout the five geographical regions. Compared to the total population of the country the number might seem small, but millions of Brazilians actually have some Indigenous ancestry. This happened mainly because of the miscegenation of indigenous tribes with colonial settlers.

Around 180 Native or autoctone languages are spoken in Brazil by 160 thousand people, many of them have threatened status. Most Natives can communicate in Portuguese and tribes in reservations have their mother tongue and Portuguese taught at schools. Today 517 thousand people live in Indigenous reservations.

Genetic studies

Genetic studies have shown the Brazilian population as a whole to have European, African and Native Americans components.

Autosomal studies

A 2015 autosomal genetic study, which also analysed data of 25 studies of 38 different Brazilian populations concluded that: European ancestry accounts for 62% of the heritage of the population, followed by the African (21%) and the Native American (17%). The European contribution is highest in Southern Brazil (77%), the African highest in Northeast Brazil (27%) and the Native American is the highest in Northern Brazil (32%).[106]

| Region[106] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 16% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 58% | 27% | 15% |

| Central-West Region | 64% | 24% | 12% |

| Southeast Region | 67% | 23% | 10% |

| South Region | 77% | 12% | 11% |

An autosomal study from 2013, with nearly 1300 samples from all of the Brazilian regions, found a pred. degree of European ancestry combined with African and Native American contributions, in varying degrees. 'Following an increasing North to South gradient, European ancestry was the most prevalent in all urban populations (with values up to 74%). The populations in the North consisted of a significant proportion of Native American ancestry that was about two times higher than the African contribution. Conversely, in the Northeast, Center-West and Southeast, African ancestry was the second most prevalent. At an intrapopulation level, all urban populations were highly admixed, and most of the variation in ancestry proportions was observed between individuals within each population rather than among population'.[107]

| Region[108] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 51% | 17% | 32% |

| Northeast Region | 56% | 28% | 16% |

| Central-West Region | 58% | 26% | 16% |

| Southeast Region | 61% | 27% | 12% |

| South Region | 74% | 15% | 11% |

An autosomal DNA study (2011), with nearly 1000 samples from every major race group ("whites", "pardos" and "blacks", according to their respective proportions) all over the country found out a major European contribution, followed by a high African contribution and an important Native American component.[109] "In all regions studied, the European ancestry was predominant, with proportions ranging from 60.6% in the Northeast to 77.7% in the South". The 2011 autosomal study samples came from blood donors (the lowest classes constitute the great majority of blood donors in Brazil[110]), and also public health institutions personnel and health students.

| Region[109] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Brazil | 68.80% | 10.50% | 18.50% |

| Northeast Brazil | 60.10% | 29.30% | 8.90% |

| Southeast Brazil | 74.20% | 17.30% | 7.30% |

| Southern Brazil | 79.50% | 10.30% | 9.40% |

According to an autosomal DNA study from 2010, "a new portrayal of each ethnicity contribution to the DNA of Brazilians, obtained with samples from the five regions of the country, has indicated that, on average, European ancestors are responsible for nearly 80% of the genetic heritage of the population. The variation between the regions is small, with the possible exception of the South, where the European contribution reaches nearly 90%. The results, published by the scientific magazine American Journal of Human Biology by a team of the Catholic University of Brasília, show that, in Brazil, physical indicators such as skin colour, colour of the eyes and colour of the hair have little to do with the genetic ancestry of each person, which has been shown in previous studies (regardless of census classification).[111] "Ancestry informative SNPs can be useful to estimate individual and population biogeographical ancestry. Brazilian population is characterized by a genetic background of three parental populations (European, African, and Brazilian Native Amerindians) with a wide degree and diverse patterns of admixture. In this work we analyzed the information content of 28 ancestry-informative SNPs into multiplexed panels using three parental population sources (African, Amerindian, and European) to infer the genetic admixture in an urban sample of the five Brazilian geopolitical regions. The SNPs assigned apart the parental populations from each other and thus can be applied for ancestry estimation in a three hybrid admixed population. Data was used to infer genetic ancestry in Brazilians with an admixture model. Pairwise estimates of F(st) among the five Brazilian geopolitical regions suggested little genetic differentiation only between the South and the remaining regions. Estimates of ancestry results are consistent with the heterogeneous genetic profile of Brazilian population, with a major contribution of European ancestry (0.771) followed by African (0.143) and Amerindian contributions (0.085). The described multiplexed SNP panels can be useful tool for bioanthropological studies but it can be mainly valuable to control for spurious results in genetic association studies in admixed populations".[108] It is important to note that "the samples came from free of charge paternity test takers, thus as the researchers made it explicit: "the paternity tests were free of charge, the population samples involved people of variable socioeconomic strata, although likely to be leaning slightly towards the pardo group".[108]

| Region[108] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 71.10% | 18.20% | 10.70% |

| Northeast Region | 77.40% | 13.60% | 8.90% |

| Central-West Region | 65.90% | 18.70% | 11.80% |

| Southeast Region | 79.90% | 14.10% | 6.10% |

| South Region | 87.70% | 7.70% | 5.20% |

An autosomal DNA study from 2009 found a similar profile "all the Brazilian samples (regions) lie more closely to the European group than to the African populations or to the Mestizos from Mexico".[112]

| Region[112] | European | African | Native American |

|---|---|---|---|

| North Region | 60.6% | 21.3% | 18.1% |

| Northeast Region | 66.7% | 23.3% | 10.0% |

| Central-West Region | 66.3% | 21.7% | 12.0% |

| Southeast Region | 60.7% | 32.0% | 7.3% |

| South Region | 81.5% | 9.3% | 9.2% |

According to another autosomal DNA study from 2008, by the University of Brasília (UnB), European ancestry dominates in the whole of Brazil (in all regions), accounting for 65.90% of ancestry of the population, followed by the African contribution (24.80%) and the Native American (9.3%).[113]

[114] A more recent study, from 2013, found the following composition in São Paulo state: 61,9% European, 25,5% African and 11,6% Native American.[107]

A 2014 autosomal DNA study, which analysed data from 1594 samples from all of the Brazilian regions, found that Brazilians show widespread European ancestry with the highest levels being observed in the south. African ancestry is also widespread (except for the south) and reaches its highest values in the East of the country. Native American ancestry is highest in the north-west (Amazonia). In conclusion, European ancestry accounts for 82% of the heritage of the population, followed by the African (9%) and the Native American (9%).[115]

MtDna and y DNA studies

Haplogroup frequencies do not determine phenotype nor admixture. They are very general genetic snapshots, primarily useful in examining past population group migratory patterns. Only autosomal DNA testing can reveal admixture structures, since it analyses millions of alleles from both maternal and paternal sides. Contrary to yDNA or mtDNA, which are focused on one single lineage (paternal or maternal) the autosomal DNA studies profile the whole ancestry of a given individual, being more accurate in describing the complex patterns of ancestry in a given place. According to a genetic study in 2000 who analysed 247 samples (mainly identified as "white" in Brazil) who came from four of the five major geographic regions of the country, the mtDNA pool (maternal lineages) of present-day Brazilians clearly reflects the imprints of the early Portuguese colonization process (involving directional mating), as well as the recent immigrant waves (from Europe) of the last century.[116]

| Continental Fraction | Brazil | Northern | Northeastern | Southeastern | Southern |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Native American | 33% | 54% | 22% | 33% | 22% |

| African | 28% | 15% | 44% | 34% | 12% |

| European | 39% | 31% | 34% | 31% | 66% |

According to a study in 2001, the vast majority of Y chromosomes (male lineages) in white Brazilian males, regardless of their regional source, is of European origin (>90% contribution), with a very low frequency of sub-Saharan African chromosomes and a complete absence of Amerindian contributions. These results configure a picture of strong directional mating in Brazil involving European males, on one side, and European, African and Amerindian females, on the other.[29]

In a study from 2016, the authors investigated a set of 41 Y-SNPs in 1217 unrelated males from the five Brazilian geopolitical regions. A total of 22 haplogroups were detected in the whole Brazilian sample, revealing the three major continental origins of the current population, namely from America, Europe and Africa. The genetic differences observed among regions were, however, consistent with the colonization history of the country. The sample from the Northern region presented the highest Native American ancestry (8.4%), whereas the more pronounced African contribution could be observed in the Northeastern population (15.1%). The Central-Western and Southern samples showed the higher European contributions (95.7% and 93.6%, respectively). The Southeastern region presented significant European (86.1%) and African (12.0%) contributions. Portugal was estimated to be the main source of the male European lineages to Central-West, Southeast and South Brazil. The North and the Northeast showed the highest contribution from France and Italy, respectively. The highest migration rate from Lebanon was to the Central-Weast, whereas a significant migration from Germany was observed to the Central East, Southeast and South.[117]

In the Brazilian "white" and "pardos" the autosomal ancestry (the sum of the ancestors of a given individual) tends to be in most cases predominantly European, with often a non European mtDNA (which points to a non European ancestor somewhere down the maternal line), which is explained by the women marrying newly arrived colonists, during the formation of the Brazilian people.[118]

See also

- Lists of Brazilians

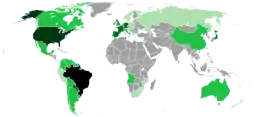

- Brazilian diaspora

- Demographics of Brazil

- Pardo (Brown) Brazilians

- European immigration to Brazil

- White Brazilians

- Portuguese Brazilians

- Italian Brazilians

- Spanish Brazilians

- German Brazilians

- Arab Brazilians

- Confederados

- History of the Jews in Brazil

- Native Brazilians

- Afro-Brazilians

- Asian Brazilians

- Japanese Brazilians

References

- "Projeção da população". Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Retrieved September 16, 2019.

- "Brasileiros no Mundo - Estimativas" [Brazilians Around The World - Estimations] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Ministry of External Relations. 2015-03-28. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- "Brasileiros no Mundo - Estimativas" [Brazilians Around The World - Estimations] (PDF) (in Portuguese). Ministry of External Relations. 2015-03-28. Retrieved 2016-03-24.

- "Table 1.3: Overseas-born population in the United Kingdom, excluding some residents in communal establishments, by sex, by country of birth, January 2018 to December 2018". Office for National Statistics. 24 May 2019. Retrieved 15 August 2019. Figure given is the central estimate. See the source for 95% confidence intervals.

- "Ethnic Origin, both sexes, age (total), Canada, 2016 Census – 25% Sample data". Canada 2016 Census. Statistics Canada. 2019-02-20. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- https://www.emol.com/noticias/Nacional/2018/04/09/901867/Extranjeros-en-Chile-superan-el-millon-110-mil-y-el-72-se-concentra-en-dos-regiones-Antofagasta-y-Metropolitana.html/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - https://www.migrationpolicy.org/programs/data-hub/charts/immigrant-and-emigrant-populations-country-origin-and-destination

- "Brazil". Ethnologue. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- "Brasil possui 5 línguas indígenas com mais de 10 mil falantes-Fonte: Agência Brasil". ebc. 2014-12-11. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- "Hunsrick". Ethnologue. Retrieved 20 July 2015.

- "Olivet Second Most Spoken Languages Around the World". olivet.edu. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- "Venetian or Talian". Ethnologue. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Costa, Luciane Trennephol da; Gielinski, Márcia Inês (17 August 2014). "DETALHES FONÉTICOS DO POLONÊS FALADO EM MALLET". Revista (Con)textos Linguísticos. 8 (10): 159–174 – via periodicos.ufes.br.

- Delong, Silvia Regina; Kersch, Dorotea Frank (17 September 2014). "Perfil de descendentes de poloneses residentes no sul do Brasil: a constituição da(s) identidade(s)". Domínios de Lingu@gem. 8 (3): 65–85. doi:10.14393/DLesp-v8n3a2014-5.

- "O panorama lingüístico brasileiro: a coexistência de línguas minoritárias com o português" (PDF).

- Oksana Boruszenko and Rev. Danyil Kozlinsky (1994). Ukrainians in Brazil (Chapter), in Ukraine and Ukrainians Throughout the World, edited by Ann Lencyk Pawliczko, University of Toronto Press: Toronto, pp. 443–454

- "E o terceiro fluxo, entre 1949 e 1965, quando chegaram ao Brasil aproximadamente 25 mil russos refugiados da revolução cultural chinesa". noticias.terra.com.br. 2015-06-13. Retrieved 2016-05-05.

- "Vlax Romani in Brazil". Ethnologue. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- Freyre, Gilberto (2000). Ingleses no Brasil: aspectos da influência britânica sobre a vida, a paisagem e a cultura do Brasil (in Portuguese). Topbook. ISBN 9788574750231.

- "Ingleses no Brasil do século XIX". livrariacultura. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

- Harter, Eugene C. (2000). The Lost Colony of the Confederacy. Texas A & M University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-1585441020.

- "Edwin S. James research materials". University of South Carolina. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- "MCMULLAN, FRANCIS". Texas State Historical Association. 2010-06-15. Retrieved 2014-01-05.

- Tania Cantrell Rosas-Moreno (2014). News and Novela in Brazilian Media: Fact, Fiction, and National Identity. Lexington Books. p. 87. ISBN 9780739189795.

- Censo Demografico 2010/Caracteristicas Gerais Religiao Deficiencia

- Some regional pronunciations include [bɾaziˈleɪ̯ɾʊs] in São Paulo and much of Southern Brazil, and [bɾɐziˈleiɾuiʃ] in Rio de Janeiro.

- Facioli, Valentim (25 February 2018). Um defunto estrambótico: análise e interpretação das Memórias póstumas de Brás Cubas. EdUSP. ISBN 9788531410833 – via Google Books.

- Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil, Artigo 12, I.

- Carvalho-Silva, DR; Santos, FR; Rocha, J; Pena, SD (January 2001). "The Phylogeography of Brazilian Y-Chromosome Lineages". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 68 (1): 281–6. doi:10.1086/316931. PMC 1234928. PMID 11090340.

- "Presença portuguesa: de colonizadores a imigrantes" (in Portuguese). Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. Retrieved 2020-12-29.

- Telfer (1932), p. 184.

- Bethell (1984), p. 47.

- "Desmundo de Alain Fresnot, o Brasil no século XVI". ensinarhistoria. 2015-02-27. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- "Desmundo by Ana Miranda (1996)". companhiadasletras.com.br. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- "Brazil - Modern-Day Community". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/. 2013. Retrieved 2013-12-22.

- "Judeus no Brasil. Vida social, política e cultural". ibge. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- Samuel L. Baily; Eduardo José Míguez (2003). Mass Migration to Modern Latin America. Rowman & Littlefield. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-8420-2831-8. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- "Províncias de origem dos imigrantes italianos". ibge. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- "Principais levas de imigração para o Brasil". Abril. Retrieved 6 April 2016.

- "Entrada de estrangeiros no Brasil". Retrieved 2014-01-23.

- Zirin, Dave (2014). "The beginning of the 'Mosaic'" (PDF). Brazil's Dance with the Devil: The World Cup, The Olympics and the Fight for Democracy. Chicago: Haymarket Books. ISBN 978-1-60846-433-3.

- Marília D. Klaumann Cánovas (2004). "A GRANDE IMIGRAÇÃO EUROPÉIA PARA O BRASIL E O IMIGRANTE ESPANHOL NO CENÁRIO DA CAFEICULTURA PAULISTA: ASPECTOS DE UMA (IN)VISIBILIDADE" [The great European immigration to Brazil and immigrants within the Spanish scenario of the Paulista coffee plantations: one of the issues (in) visibility] (PDF) (in Portuguese). cchla.ufpb.br. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2009.

- "Regiões de origem e de destino dos imigrantes teutônicos". ibge. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- "Os imigrantes teutônicos no Brasil- alemães, austríacos, luxemburgueses, pomeranos e volga". ibge. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- Altenhofen, Cléo Vilson: Hunsrückisch in Rio Grande do Sul, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1996, p. 24.

- "O alemão lusitano do Sul do Brasil - Cultura europeia, dos clássicos da arte a novas tendências - DW - 20.04.2004". DW.COM.

- "Research Professor, A.C. Van Raalte Institute, Hope College, Holland, Michigan, USA". Twelfth International Economic History Conference, Madrid, Spain, August 28, 1998 (Session C-31). Retrieved 2016-05-04.

- "Paraná State Government page". Cidadao.pr.gov.br. Retrieved 2014-01-23.

- Tyciński, Wojciech; Sawicki, Krzysztof (2009). "Raport o sytuacji Polonii i Polaków za granicą (The official report on the situation of Poles and Polonia abroad)" (PDF). Warsaw: Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Poland). pp. 1–466. Archived from the original (PDF file, direct download 1.44 MB) on July 21, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- "Restauração da igreja ortodoxa de Mallet - Marco da valorização da presença eslava no Sul do Brasil". vanhoni.com. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "Inaugurado o restauro da igreja ortodoxa de São Miguel Arcanjo em Mallet - Marco da imigração ucraniana no Brasil". Representação Central Ucraniano-Brasileira. Retrieved 29 May 2016.

- "Câmara de Comércio Brasil-Rússia". Brasil-russia.com.br. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- Moschella, Alexandre (24 June 2002). "Um atalho para a Europa". Epoca (in Portuguese). Editora Globo S.A. Archived from the original on 3 July 2013.

- "Embaixada da Hungria no Brasil sobre as estatísticas de descendentes de húngaros". mfa.gov.hu. Archived from the original on 2016-11-12. Retrieved 2016-05-04.

- "The Situation of Hungarians Living outside the Carpathian Basin". Chef Lazlo. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017.

- "Oscar Cox". Fluminense Football Club. Archived from the original on 2009-11-12. Retrieved 2010-01-10.

- Parmakson, Annemari (2 October 2017). "Lavastus, mis ei räägi 3400 eestlase väljarändest Brasiiliasse". Eesti Päevaleht (in Estonian).

- Žemaitis, Augustinas. "Brazil". global.truelithuania.com.

- "Brazil Brown Bag Seminar Series – Lithuanian Diaspora in the Americas by Erick Reis Godliauskas Zen. Organizer: Lemann Center for Brazilian Studies". ilas.columbia.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-04-15. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- Oreck, Alden. "Brazil Virtual Jewish History Tour". www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org. American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise.

- "Arab roots grow deep in Brazil's rich melting pot". Washington Times. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- "Origem e destino dos imigrantes do Levante". ibge. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- Gonzalez, David (September 25, 2013). "Japanese-Brazilians: Straddling Two Cultures". Lens Blog. The New York Times. Retrieved September 27, 2013.

- "Japan, Brazil mark a century of settlement, family ties | The Japan Times Online". 2008-01-15.

- Bianconi, Nara (27 June 2008). "Nipo-brasileiros estão mais presentes no Norte e no Centro-Oeste do Brasil". Centenário da Imigração Japonesa (in Portuguese). www.japao100.com.br. Archived from the original on 13 August 2017. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- IBGE traça perfil dos imigrantes Archived November 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Eugene C. Harter. "The Lost Colony of the Confederacy". Texas A&M University Press, 1985, p. 74.

- "Economia brasileira atrai estrangeiros e imigração aumenta 50% em seis meses". Portal Brasil. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Brazil has 689,000 people from around the world in 2009. Bv.fapesp.br. Retrieved on 2012-05-19.

- "Estudo descobre 31 milhões de portugueses pelo mundo". dn.pt. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2014-08-24.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Só o Brasil concedeu mais de 52 mil vistos de residência nos primeiros 6 meses". Graciano Coutinho OPovo. Archived from the original on 2017-08-19. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "Imigração aumenta 50 por cento em seis meses". brasil.gov.br. Retrieved 7 April 2016.

- "G1 - Brasil tem hoje 5,2 mil refugiados de 79 nacionalidades - notícias em Mundo". Mundo. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Pena, Sérgio D. J.; Di Pietro, Giuliano; Fuchshuber-Moraes, Mateus; Genro, Julia Pasqualini; Hutz, Mara H.; Kehdy, Fernanda de Souza Gomes; Kohlrausch, Fabiana; Magno, Luiz Alexandre Viana; Montenegro, Raquel Carvalho; Moraes, Manoel Odorico; de Moraes, Maria Elisabete Amaral (2011-02-16). "The Genomic Ancestry of Individuals from Different Geographical Regions of Brazil Is More Uniform Than Expected". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226.

- "Brazil, the case of triracial white people". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 2020-08-13.

- "Sistema IBGE de Recuperação Automática - SIDRA". ibge.gov.br.

- Genealogy: German migration to Brazil. Genealogienetz.de. Retrieved on 2012-05-19.

- Sistema IBGE de Recuperação Automática - SIDRA (PDF) (in Portuguese). State of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: IBGE. 2008. ISBN 978-85-240-3919-5. Retrieved 2014-08-24.

- Tabela 262 - População residente, por cor ou raça, situação e sexo (vide Nota de Rodapé) (PDF) (in Portuguese). Espírito Santo, Brazil: IBGE. 2012. ISBN 978-85-240-3919-5. Retrieved 2014-08-08.

- "Japan-Brazil Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

- Phillip Wagner Sugar and Blood. Brazzil Magazine, April 2002

- Sources :: Indigenous Peoples in Brazil – ISA. socioambiental.org

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística Archived 2007-08-25 at the Wayback Machine. IBGE (2007-05-25). Retrieved on 2012-05-19.

- 2008 PNAD, IBGE. "População residente por cor ou raça, situação e sexo Archived 2011-06-14 at the Wayback Machine".

- Pena, S.D.J.; Bastos-Rodrigues, L.; Pimenta, J.R.; Bydlowski, S.P. (11 September 2009). "DNA tests probe the genomic ancestry of Brazilians". Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 42 (10): 870–876. doi:10.1590/S0100-879X2009005000026. PMID 19738982.

- "Censo Demográfi co 2010 Características da população e dos domicílios Resultados do universo" (PDF). 8 November 2011. Retrieved 2014-07-12.

- "CIA data from The World Factbook's Field Listing :: Ethnic groups and Field Listing :: Population". cia.gov. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Fran cisco Lizcano Fernández (May 2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" (PDF). Convergencia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-02-24. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Nova Veneza Archived 2008-08-19 at the Wayback Machine

- POMERODE-SC

- Ucranianos no Brasil

- História de Treze Tílias Archived 2008-11-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Prefeitura de D. Feliciano Archived July 6, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Karen, Pupp Spinassé (25 February 2018). "Os imigrantes alemães e seus descendentes no Brasil : a língua como fator identitário e inclusivo". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Altenhofen, Cléo Vilson: Hunsrückisch in Rio Grande do Sul, Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1996

- "Hunsrik". Ethnologue.

- Venetian at Ethnologue (16th ed., 2009)

- "Yiddish, Western".

- "A Presença Britânica e a Língua Inglesa na Corte de D. João. Escrito por Joselita Júnia Viegas Vidotti (USP)". USP. ISSN 1981-6677. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- Emmel, Ina (2005), "Die kann nun nich', die is' beim treppenputzen!" O Progressivo No Alemão De Pomerode–SC (PDF) (in Portuguese), Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina

- "Sistema Legis". www.al.rs.gov.br.

- "Texto da Norma". www.al.rs.gov.br.

- Cliff Pereira, in Van Tilburg, H., Tripati, S., Walker Vadillo, V., Fahy, B., and Kimura, J. (eds.), "East in the West : Investigating the Asian presence and influence in Brazil from the 16th to 18th centuries." The MUA Collection.

- Rodrigues De Moura, Ronald; Coelho, Antonio Victor Campos; De Queiroz Balbino, Valdir; Crovella, Sergio; Brandão, Lucas André Cavalcanti (2015). "Meta-analysis of Brazilian genetic admixture and comparison with other Latin America countrieBold text". American Journal of Human Biology. 27 (5): 674–80. doi:10.1002/ajhb.22714. PMID 25820814. S2CID 25051722.

- Saloum De Neves Manta, Fernanda; Pereira, Rui; Vianna, Romulo; Rodolfo Beuttenmüller De Araújo, Alfredo; Leite Góes Gitaí, Daniel; Aparecida Da Silva, Dayse; De Vargas Wolfgramm, Eldamária; Da Mota Pontes, Isabel; Ivan Aguiar, José; Ozório Moraes, Milton; Fagundes De Carvalho, Elizeu; Gusmão, Leonor (2013). "Revisiting the Genetic Ancestry of Brazilians Using Autosomal AIM-Indels". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e75145. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...875145S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0075145. PMC 3779230. PMID 24073242.

- Lins, T. C.; Vieira, R. G.; Abreu, B. S.; Grattapaglia, D.; Pereira, R. W. (March–April 2009). "Genetic composition of Brazilian population samples based on a set of twenty-eight ancestry informative SNPs". American Journal of Human Biology. 22 (2): 187–192. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20976. PMID 19639555. S2CID 205301927.

- Pena, Sérgio D. J.; Di Pietro, Giuliano; Fuchshuber-Moraes, Mateus; Genro, Julia Pasqualini; Hutz, Mara H.; Kehdy, Fernanda de Souza Gomes; Kohlrausch, Fabiana; Magno, Luiz Alexandre Viana; et al. (2011). Harpending, Henry (ed.). "The Genomic Ancestry of Individuals from Different Geographical Regions of Brazil Is More Uniform Than Expected". PLOS ONE. 6 (2): e17063. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617063P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017063. PMC 3040205. PMID 21359226.

- Profile of the Brazilian blood donor Archived October 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Amigodoador.com.br. Retrieved on 2012-05-19.

- DNA de brasileiro é 80% europeu, indica estudo. .folha.uol.com.br (1970-01-01). Retrieved on 2012-05-19.

- De Assis Poiares, Lilian; De Sá Osorio, Paulo; Spanhol, Fábio Alexandre; Coltre, Sidnei César; Rodenbusch, Rodrigo; Gusmão, Leonor; Largura, Alvaro; Sandrini, Fabiano; Da Silva, Cláudia Maria Dornelles (2010). "Allele frequencies of 15 STRs in a representative sample of the Brazilian population" (PDF). Forensic Science International: Genetics. 4 (2): e61–3. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2009.05.006. PMID 20129458. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-08.

- "the impact of migrations in the constitution of Latin American populations" (PDF).

- Ferreira, L. B.; Mendes-Junior, C. T.; Wiezel, C. E.; Luizon, M. R.; Simões, A. L. (2006). "Genomic ancestry of a sample population from the state of São Paulo, Brazil". American Journal of Human Biology. 18 (5): 702–705. doi:10.1002/ajhb.20474. PMID 16917899. S2CID 10103856.

- Ruiz-Linares, Andrés; Adhikari, Kaustubh; Acuña-Alonzo, Victor; Quinto-Sanchez, Mirsha; Jaramillo, Claudia; Arias, William; Fuentes, Macarena; Pizarro, María; Everardo, Paola; De Avila, Francisco; Gómez-Valdés, Jorge; León-Mimila, Paola; Hunemeier, Tábita; Ramallo, Virginia; Silva De Cerqueira, Caio C.; Burley, Mari-Wyn; Konca, Esra; De Oliveira, Marcelo Zagonel; Veronez, Mauricio Roberto; Rubio-Codina, Marta; Attanasio, Orazio; Gibbon, Sahra; Ray, Nicolas; Gallo, Carla; Poletti, Giovanni; Rosique, Javier; Schuler-Faccini, Lavinia; Salzano, Francisco M.; Bortolini, Maria-Cátira; et al. (2014). "Admixture in Latin America: Geographic Structure, Phenotypic Diversity and Self-Perception of Ancestry Based on 7,342 Individuals". PLOS Genetics. 10 (9): e1004572. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004572. PMC 4177621. PMID 25254375.

- Alvessilva, J; Dasilvasantos, M; Guimaraes, P; Ferreira, A; Bandelt, H; Pena, S; Prado, V (2000). "The Ancestry of Brazilian mtDNA Lineages". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 67 (2): 444–61. doi:10.1086/303004. PMC 1287189. PMID 10873790.

- Resque, Rafael; Gusmão, Leonor; Geppert, Maria; Roewer, Lutz; Palha, Teresinha; Alvarez, Luis; Ribeiro-Dos-Santos, Ândrea; Santos, Sidney (2016). "Male Lineages in Brazil: Intercontinental Admixture and Stratification of the European Background, Resque et al. (2016)". PLOS ONE. 11 (4): e0152573. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1152573R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0152573. PMC 4821637. PMID 27046235.

- "Laboratório GENE – Núcleo de Genética Médica". Laboratoriogene.com.br. Retrieved 2011-12-29.