Peshtigo fire

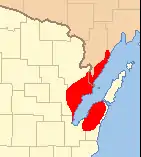

The Peshtigo fire was a very large forest fire that took place on October 8, 1871, in northeastern Wisconsin, United States, including much of the southern half of the Door Peninsula and adjacent parts of the Upper Peninsula of Michigan. The largest community in the affected area was Peshtigo, Wisconsin. The fire burned approximately 1,200,000 acres (490,000 ha) and is the deadliest wildfire in recorded history,[1] with the number of deaths estimated between 1,500[1] and 2,500.[2]

| Peshtigo fire | |

|---|---|

Extent of wildfire damage | |

| Location | Peshtigo, Wisconsin |

| Coordinates | 45.05°N 87.75°W |

| Statistics | |

| Cost | Unknown |

| Date(s) | October 8, 1871 |

| Burned area | 1,200,000 acres (490,000 ha) |

| Cause | Small fires whipped up by high winds in dry conditions |

| Deaths | 1,500–2,500 (estimated) |

| Map | |

| |

Occurring on the same day as the more famous Great Chicago Fire, the Peshtigo fire has been largely forgotten, even though it killed far more people.[3][4] Several cities in Michigan, including Holland and Manistee (across Lake Michigan from Peshtigo) and Port Huron (at the southern end of Lake Huron), also had major fires on the same day.

Firestorm

The setting of small fires was a common way to clear forest land for farming and railroad construction. On the day of the Peshtigo fire, a cold front moved in from the west, bringing strong winds that fanned the fires out of control and escalated them to massive proportions.[5] A firestorm ensued. In the words of Gess and Lutz, in a firestorm "superheated flames of at least 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit ... advance on winds of 110 miles per hour or stronger. The diameter of such a fire ranges from one thousand to ten thousand feet ... When a firestorm erupts in a forest, it is a blowup, nature's nuclear explosion ... "[6]:101

By the time it was over, 1,875 square miles (4,860 km2 or 1.2 million acres) of forest had been consumed,[7][8][9] an area fifty percent larger than the U.S. state of Rhode Island. Twelve communities were destroyed.

An accurate death toll has never been determined because all local records were destroyed in the fire. It's estimated that anywhere between 1,200 to 2,500 people lost their lives. The 1873 Report to the Wisconsin Legislature listed 1,182 names of dead or missing residents.[10] In 1870, the Town of Peshtigo had 1,749 residents.[11][12] More than 350 bodies were buried in a mass grave,[13] primarily because so many people had died that there was no one left alive who could identify them.

The fire jumped across the Peshtigo River and burned both sides of the town.[14] Survivors reported that the firestorm generated a fire whirl (described as a tornado) that threw rail cars and houses into the air. Many escaped the flames by immersing themselves in the Peshtigo River, wells, or other nearby bodies of water. Some drowned while others succumbed to hypothermia in the frigid river. The Green Island Light was kept lit during the day because of the obscuring smoke, but the three-masted schooner George L. Newman was wrecked offshore, although the crew was rescued.[15]

At the same time, another fire burned parts of the Door Peninsula; because of the coincidence, some incorrectly assumed that the fire had jumped across the waters of Green Bay.[16][note 1] In Robinsonville (now Champion) on the Door Peninsula, Sister Adele Brise and other nuns, farmers, and families fled to a local chapel for protection. Although the chapel was surrounded by flames, it survived.[17][18][19] It spared the then Village of Sturgeon Bay, which at the time remained east of the village's bay.

Comet theory

One speculation, first suggested in 1883, was that the occurrence of the Peshtigo and Chicago fires on the same day was not just a coincidence, but that all the major fires that occurred in Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin on that day were caused by the impact from fragments of Biela's Comet. This theory was revived in a 1985 book,[20] studied in a 1997 documentary,[21] and investigated in a 2004 paper to the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics.[22] Additionally, various aspects of the behaviors of the Chicago and Peshtigo fires were cited to support the idea of an extraterrestrial cause.[23] However, scientists with expertise in the area point out that there has never been a credible report of a fire being started by a meteorite.[24][25]

In any event, no external source of ignition was needed. There were already numerous small fires burning in the area from land-clearing operations (and other such sources) after a tinder-dry summer.[6][26] These fires alone generated so much smoke that the Green Island Light was kept lit continuously for weeks before the main fire started.[27] All that was needed to generate the firestorm, as well as other large fires in the Midwest, was a strong wind from the front, which had moved in that very evening.[26]

Legacy

The Peshtigo Fire Museum, just west of U.S. Highway 41, has a small collection of artifacts from the fire, first-person descriptions of the event, and a graveyard dedicated to victims of the tragedy. A memorial commemorating the fire was dedicated on October 8, 2012 at the bridge over the Peshtigo River.[28]

The chapel where Sister Adele Brise and others sheltered from the fire has become the National Shrine of Our Lady of Good Help. The site is a Marian shrine, where visitors can make religious pilgrimages.[19]

The combination of wind, topography and ignition sources that created the firestorm, primarily representing the conditions at the boundaries of human settlement and natural areas, is known as the "Peshtigo Paradigm".[29] The condition was closely studied by the American and British military during World War II to learn how to recreate firestorm conditions for bombing campaigns against cities in Germany and Japan. The severe bombing of Tokyo by incendiary devices resulted in death tolls comparable to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[29]

See also

Other October 8, 1871, fires

Other fire disasters in the Great Lakes

- Great Hinckley Fire of 1894

- Baudette fire of 1910

- Cloquet fire of 1918

- Thumb Fire of 1881 (see also List of Michigan wildfires)

Notes

- "Because of the timing, many people later thought—incorrectly, it now appears—that this fire was an offshoot of the one that had struck Peshtigo and that it had somehow jumped across the 30-mile-wide bay."[16]

References

- Biondich, S. (June 9, 2010). "The Great Peshtigo Fire". Shepherd Express. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- Knickelbine, Scott (August 29, 2012). The Great Peshtigo Fire: Stories and Science from America's Deadliest Fire. Wisconsin Historical Society Press. ISBN 978-0870206023.

- Christine Gibson (August–September 2006). "Our 10 Greatest Natural Disasters". American Heritage. 57 (4).

- John Steele Gordon (April–May 2003). "Forgotten Fury". American Heritage. 55 (4).

- Hemphill, Stephanie (November 27, 2002). "Peshtigo: a tornado of fire revisited". News and Features. Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved March 30, 2008.

- Gess, D.; Lutz, W. (2003). Firestorm at Peshtigo: A Town, Its People, and the Deadliest Fire in American History. New York, NY: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-7293-8. OCLC 52421495.

- Kim Estep. "The Peshtigo Fire" Green Bay Press-Gazette. National Weather Service.

- Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Wisconsin Wildfires > 250 Acres, 1871 — Present. September 11, 2017.

- Everett Rosenfeld. Top 10 Devastating Wildfires: The Peshtigo Fire, 1871". Time, June 8, 2011.

- Wisconsin. Legislature. Assembly (1873). Journal of Proceedings. pp. 167–172. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- "1870 Census of Population and Housing". census.gov. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013.

- "1870 Federal Census of town of Peshtigo". Rootsweb.ancestry.com. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- Peshtigo Fire Cemetery (registered historic marker). 1951.

- Hipke, Deana C. "The Great Peshtigo Fire of 1871". Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- "Green Island Lighthouse". Terry Pepper. Retrieved November 26, 2010.

- Watson, Benjamin A. 1993. Acts of God: The Old Farmer's Almanac Unpredictable Guide to Weather and Natural Disasters. New York: Random House, p. 106.

- "Shrine escaped devastation of Peshtigo Fire", The Compass, February 17, 2011. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- "Robinsonville: A Wisconsin Shrine of Mary", Catholic Herald, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, May 23, 1935. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- Cipin, Vojtech (2011). "Troubles and Miracles". Shrine of Our Lady of Good Help. Archived from the original on November 27, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- Waskin, Mel (1985). Mrs. O'Leary's Comet: Cosmic Causes of the Great Chicago Fire. Academy Chicago Publishers. ISBN 0897331818.

- Fire From The Sky. WTBS. 1997.

- Wood, Robert M. (2004). "Did Biela's Comet Cause The Chicago And Midwest Fires?" (PDF). American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- Bales, R. F.; Schwartz, T. F. (April 2005). "Debunking Other Myths". The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O'Leary's Cow. McFarland. pp. 101–104. ISBN 978-0-7864-2358-3. OCLC 68940921.

- Calfee, Mica (February 2003). "Was It A Cow Or A Meteorite?". Meteorite Magazine. 9 (1). Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- "Meteorites Don't Pop Corn". NASA Science. NASA. July 27, 2001. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- Bales, R. F.; Schwartz, T. F. (April 2005). "Debunking Other Myths". The Great Chicago Fire and the Myth of Mrs. O'Leary's Cow. McFarland. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-7864-2358-3. OCLC 68940921.

- "Keepers of the Light – 1871 account". Survivor Stories of the Peshtigo Fire. Oconto County WIGenWeb Project. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- "Large Crowd Attends Fire Monument Event." 2012. Peshtigo Times (11 October).

- Tasker, G. (October 10, 2003). "Worst fire largely unknown". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

Further reading

- Ball, Jacqueline A. Wildfire! The 1871 Peshtigo Firestorm. New York: Bearport Pub., 2005. ISBN 1597160113.

- Bergstrom, Bill (June 2003). Peshtigo. Philadelphia: Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1401098889..

- Holbrook, Stewart. "Fire Makes Wind: Wind Makes Fire". American Heritage, vol. 7, no. 5 (August 1956).

- Leschak, Peter M. Ghosts of the Fireground: Echoes of the Great Peshtigo Fire and the Calling of a Wildland Firefighter, New York:HarperCollins, 2003. ISBN 0062517783

- Pernin, Peter. "The Great Peshtigo Fire: An Eyewitness Account," Wisconsin Magazine of History, 54: 4 (Summer, 1971), 246–272.

- Wells, Robert W. Fire at Peshtigo. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1968.

External links

- "The Fire Fiend" New York Times, October 13, 1871.

- DeLaluzern, Guillaume (October 1871). "IN WISCONSIN. Particulars of the Burning of Williamsonville and Peshtigo – Frightful Number of Deaths". Green Bay Advocate. Archived from the original on May 31, 2013. Retrieved November 20, 2011.

- Geyer, Rev. Kurt (October 6, 1921). "History of the Peshtigo fire, October 8, 1871". Peshtigo Times. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- Hipke, Deana C. The Great Peshtigo Fire of 1871 Web site about fire with survivors' stories.

- "Peshtigo: a tornado of fire revisited". Minnesota Public Radio. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- "Survivor's stories". Rootsweb.com. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- The Great Peshtigo Fire Memorial at Find a Grave

- Peshtigo Fire at Wisconsin Historical Society's Dictionary of Wisconsin History

- "Peshtigo fire photos". Wisconsin Historical Society.