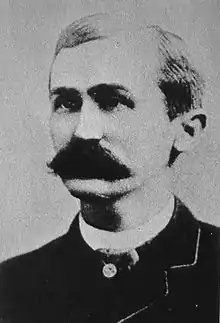

Peter French

Peter French (April 30, 1849 – December 26, 1897) was a rancher in the western United States in the late 19th century. The community of Frenchglen, Oregon was partially named for him.

Peter French | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | April 30, 1849 Missouri, United States |

| Died | December 26, 1897 (aged 48) Frenchglen, Oregon, USA |

| Occupation | Rancher |

Early life

Peter French was born John William French in Missouri on April 30, 1849. In 1850, his father moved the family to Colusa County, California, a town located in the Sacramento Valley, to begin a small ranch. Finding there was not enough room for small ranch operations due to Spanish land grants, French's father uprooted his family once again and traveled north in the valley. French's father began a sheep ranch which became very successful; however, as French grew older, he found that the work was not exciting or challenging enough for him.

French moved southward to Jacinto, California where he met and accepted employment as a horse breaker with Dr. Hugh James Glenn, a wealthy stockman and wheat baron. French was a quick learner and good worker, and in a few months he was promoted to foreman. The Spanish-speaking vaqueros liked and respected French, as he learned their language. At some point in his employment with Glenn, French assumed the name "Peter".

Glenn had expanded his assets as widely as possible in the area, and began to scout new areas for his profitable markets. In 1872, he sent French to Oregon with 1,200 head of Shorthorn cattle, a handful of vaqueros, and a Chinese cook. He ended up in southeastern Oregon to find vast grasslands amid the arid high desert.

Upon his arrival in the Catlow valley, French and his men came upon a poor prospector named Porter. Porter sold his small herd of cattle to French, and with the sale of his cattle went his squatter's rights to the west side of the Steens Mountain and his "P" brand. As French ventured further, he found the Blitzen Valley, where the Donner und Blitzen River snaked northward 40 miles (64 km) to Malheur Lake. This became his favorite spot, where he set up his base camp. He built shelters for his herd, line cabins, and bunkhouses for his men. Thus, the P Ranch was born.

Cattle king

After several years, French's small cattle operation had expanded, helped in large part by Glenn as his financier. The P Ranch became the headquarters for his growing cattle empire. He and his men built fences, drained marshlands and irrigated large areas of land, broke hundreds of horses and mules, and cut and stacked native hay. French's empire expanded to include the Diamond Valley, the Blitzen Valley, and the Catlow Valley. The land encompasses approximately 160,000 to 200,000 acres (650 to 800 km²). A shrewd businessman, French took advantage of the Swamp and Overflow Act, which allowed marshland to be purchased at $1.25 an acre. He built dams to flood areas, bought the land under the Swamp Act at the reduced price, then removed the dams to return the land to its original state. French also directed his employees and others to file homestead claims that he would then purchase. His attempts at seizing more and more land even included fencing lands in the public domain.

In 1883, French married Glenn’s daughter Ella. Glenn was murdered three weeks later by a former employee. French continued to manage the Oregon operation for the Glenn family, selling more cattle to help pay the family’s debts. In 1894, Glenn’s heirs decided to incorporate the French-Glenn partnership into the French-Glenn Livestock Company, making French the company president.[1][2] French was divorced in 1891.

In June 1878 the native Paiute and Bannock (both closely associated with the Shoshone tribes) population at the base of the Steens Mountain swooped upon the P Ranch, but not before a messenger could warn French of the impending attack. French and all but one of his men were able to escape. The attacks continued throughout the summer. The Paiutes burned buildings and homes, ran off cattle and horses, and at least once shot French's horse out from under him. At one point, French even accompanied the U.S. 1st Cavalry Regiment to guide the Army through the area.

In the 1880s and 1890s, stockmen and smaller farmers fought over land and water rights. Aggression over such rights and French's large spread of land drew a certain loathing toward him.

Death

French was shot in the head on December 26, 1897 by Edward Lee Olivier. The bullet entered between French's right eye and right ear just below his temple and exited just behind the top of his left ear. He died instantly.[3]

John William "Peter" French was buried in Red Bluff, California next to the graves of his father and mother at the Oak Hill Cemetery.

Circumstances leading to death

French's greed pushed him to harass local homesteaders in attempts to push them off their land. When French-Glenn brought Ejectment lawsuits against multiple homesteaders in 1896 and 1897, it turned the homesteaders tolerance to acrimony. French weaponized the judicial system filing suit in the faraway courthouse of Portland, Oregon. He did this for three reasons. First, to burden homesteader families by forcing them to travel. Second, to impose maximum costs on them. And third, because public sentiment in Harney County would likely prejudice a jury against French-Glenn.

The Portland court sent the case back down to Harney County courthouse where it belonged. This started a maelstrom of court filings from local homesteaders and French-Glenn alike. Tensions toward French grew to a crescendo that would ultimately lead to his death. This was no surprise to anyone, not even French himself. For years he openly shared that he believed he may end up getting himself killed.

Trial of Edward Olivier

Olivier was initially charged with murder. He pled not guilty and was let out on $10,000.00 bail that was furnished by seven local supporters. The day before the trial was to begin, the charges were dropped. Supporters of French called the trial "fixed" however, the prosecution aimed for a lesser charge of Manslaughter to counter Olivier's claim of self-defense. The trial began May 18, 1898 in the Harney County Courthouse.

Olivier had been in a dispute with French for some time about an easement that would grant Olivier the legal right to cross through a piece of French's land to get to Olivier's home. Without an easement Olivier would be forced to increase his travel by over 6 miles. It had been reported by more than a few that French made it a habit to punish Olivier for his supposed trespassing in humiliating fashion. He had quirted (whipped with a horse whip) Olivier in public at least 5 times. Lifelong rancher Alva Springer testified for the defense to French's public ridicule, "Here sits a little man who has nothing to say. You were in my field yesterday. Whenever the time comes right and I catch you there, I will fix you."[4] Several others testified to witnessing French's public promise to "fix", even "shoot", Olivier if the opportunity is ever presented.

The state had called nearing twenty witnesses, seven of which were French employees and witnessed the killing from varying distances. Their claims were more or less the same. Olivier was seen riding toward the gate that would have given him access to cross through French's land. French was at the gate working a cattle drive that day. Olivier was witnessed colliding horse to horse with French as French yelled at Olivier. French was seen swinging his hand the way one swings a whip although witnesses testified they did not actually see a whip perhaps because of the distance between them. Olivier continued westerly toward his home behind French as French had turned his horse around. Olivier drew his gun and pointed it at French's head. French ducked. Olivier lowered his gun and when French turned his head back to look at Olivier, Olivier raised his gun again and fired. French fell from his horse. Olivier stopped, looked down at French dead on the ground and rode away in the direction of his home.

Olivier's defense hinged on the purported belief that he feared that when French turned his head away, it was to buy time to draw a weapon and finally "fix" Olivier. French was not armed with a gun but was carrying his horse whip.

One of the seven witnesses that testified for the prosecution was Burt French, Pete French's brother, employee and resident of P Ranch. He testified "Never saw my brother strike Olivier with anything."[5]

Over twenty witnesses testified to Olivier's defense. One was a man by the name of J. P. Kennedy who testified that he saw Burt French in Portland, OR, on January 2, 1898, little more than a week after Pete French was killed. Kennedy testified that Burt French told him, "I don't like to say anything against my brother, but I can't blame Olivier for doing as he did."[4]

A jury found defendant, Edward Olivier, not guilty.

Controversy

If you wanted to know what happened to Pete French, you would have heard a different tale depending on where you lived. The San Francisco Chronicle received their sourcing through channels biased toward French's largesse. The Portland news accounts were no exception. It seemed the faraway cities feigned sophistication and sanctimony over the incredulity of the death of such a nobleman but the real story lay among those that lived inside of it.

A story published in the Oregonian newspaper in Portland on December 28, 1897, two days after French's killing read, "Peter French Dead - Shot and Killed by a Man Named Oliver reported to be a cold-blooded murder-affair occurred at Canyon City." An article published on 29 December in the San Francisco Chronicle read, "Killed as he fled from his assailant. How French was slain. Shot down on his own land while unarmed. The murderer escaped." On 30 December The Oregonian ran a story that said, "He [Olivier] is a man about 30 years of age, small of stature, and looks little like a criminal." These are the same publications that inaccurately reported French arriving in Harney County from Chicago on or about Christmas day. On 29 December, the San Francisco Chronicle reported "French returned a few days ago from Chicago." This comports with the account in the book, Cattle Country of Peter French[6] where French is lauded as an enterprising, heroic pioneer. It reads, "Peter French returned from a business trip to Chicago on Christmas Day of 1897. In Burns, he had Mart Brenton at the livery stable hook his team onto the buckboard, which was loaded with gifts he had brought for the children of his crew. He then drove directly to the Sod House Ranch. That night there was a Christmas Party, with all the children happy over the holiday and the men and women in a festive mood."

It is easy to deduce the sourcing of the tales of Pete French. The San Francisco Chronicle reported incorrectly and the picture painted by the book, Cattle Country of Peter French is as fanciful as it is farcical. But it was not just city folk that engaged in exaggerations about French. A local attorney in Burns, John W. Biggs, enjoyed telling the fabricated story of Pete French having Christmas Dinner with the Biggs' family the day before he was murdered. His daughter, Helen Biggs Rand outs her father in her manuscript, A Few Recollections of Burns[7] catalogued in the Harney County Library. Bias favoring the rich is nothing new.

But French returned to Harney County from Chicago, IL by way of Omaha, NE with William Hanley around the middle of December, 1897. In the December 15th, 1897 edition of the local newspaper, the Burns Times-Herald, it states, "Peter French was in town a few days this week on his way home from the east where he had been with beef cattle."

French arrived in mid December to work. His men were there to work. They worked on Christmas Day as though it were just a normal work day. And they worked the day after Christmas day when French was killed.

Mystery

There are two accounts of hearsay that unfold the greater mystery about the death of Pete French. This is the first.

Emanuel Clark was with French on Christmas Day, 1897. Clark was a member of his crew and explained his version of the death of Pete French to a man named John Scharff. The following is what he reported.

Pete French and his crew put in a day of work driving cattle on Christmas Day, 1897. His crew was made up of his right hand man, Chino, Emanuel Clark, William Gilliam, Arthur Cooper, Frank Chacarrategue, David Crow, Prim Ortego, Burt French, Pete's brother and a newcomer who went by the name Caldwell. Chino and his horse had suffered a fall and he was pretty beaten up so French traded his buckboard wagon to Chino, took Chino's horse and sent Chino off to P Ranch while French drove the cattle. Before sending Chino off, French pulled out his pistol in its scabbard from the buckboard and buckled it on as he fielded questions from his men. Then he thought different, unbuckled the pistol, put it inside his pack and instructed Chino to take his pack back to P Ranch and leave it in French's room. All that were present witnessed that French would be working unarmed.

Later that night Emanuel Clark and French decided to spend the night at the Sod House before returning to drive cattle the next morning. Caldwell, the newcomer, told French he would camp with friends and family down by the lake but would meet up with them at daylight to begin the day's work. The next day, Caldwell never showed.[4]

The second bit of hearsay comes from a woman by the name of Clara Springer. She was the granddaughter of Alva Springer, a homesteader embroiled in litigation against French over land at the time of French's killing. French had sought to make an example out of Springer who was well regarded as both tough and fair. In 1994, in research for his book, Life and Death of Oregon "Cattle King" Peter French 1849 - 1897, author Edward Gray, interviewed Clara Springer. During the interview Clara kept repeating herself, "I know something about the death of Pete French that nobody knows." It was as if a secret she had kept for too long had taken a life of its own and demanded to be told. She let it out. She said Olivier lied during his trial. Olivier said he left the George Curtis place and headed directly for his homestead on the day of the killing but Clara said that was not true. What Olivier did not tell the court was that he met up with Alva Springer on top of one of the hills overlooking French, his men, and the cattle they were driving that day. Another man named Albert Reineman Sr. was there too. She said Springer cautioned Olivier telling him he should make the extra six mile journey home.[4]

Some believe Caldwell unwittingly collected valuable information about French on that fateful Christmas Day. They say news that French was unarmed may have traveled fast. Even if it did, that does not mean that Olivier did not act in self defense but it also does not mean he was innocent either. Perhaps French's history of brazen acts of dominance over Olivier could be dependably relied on and that act could provide Olivier with a justified response. Or perhaps French was murdered in a calculated, premeditated way. Perhaps there were several conspirators to that end. We will never really know.

See also

References

- "A Little Bit of Malheur History", Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, United States Department of Interior, Princeton, Oregon, 10 November 2008.

- Pinyard, David and Donald Peting, "Preservation of the Pete French Round Barn" Archived 2010-05-27 at the Wayback Machine, CRM Cultural Resources Management (Vol. 18, No. 5), National Park Service, United States Department of Interior, Washington, D.C., 1995, pp. 30–32.

- Dr. Walter L. Marsden's "Coroner's Inquest" report on Peter French of December 27, 1897 at the Sod House Ranch.

- Gray, Edward (1995). LIFE and DEATH of OREGON "CATTLE KING" PETER FRENCH 1949 - 1897. Eugene, Oregon. p. 157. ISBN 0-9622609-8-3.

- Gray, Edward (1995). LIFE and DEATH of OREGON "CATTLE KING" PETER FRENCH 1849 - 1897. Eugene, Oregon. p. 190. ISBN 0-9622609-8-3.

- French, Giles (1972). Cattle Country of Peter French. Binfords and Mort.

- Biggs Rand, Helen. A Few Recollections of Burns. Harney County Library.

Further reading

- French, Giles. "Cattle Country of Peter French." Binfords & Mort, 1972.

- Gibson, Elizabeth. "Pete French, Cattle Baron."

- Harney County Sherriff. "The Death of Peter French."