Columbian exchange

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, named after Christopher Columbus, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the Americas, the Old World, and West Africa in the 15th and 16th centuries. It also relates to European colonization and trade following Christopher Columbus's 1492 voyage.[1] Invasive species, including communicable diseases, were a byproduct of the exchange. The changes in agriculture significantly altered global populations. The most significant immediate effects of the Columbian exchange were the cultural exchanges and the transfer of people (both free and enslaved) between continents.

The new contacts among the global population resulted in the circulation of a wide variety of crops and livestock, which supported increases in population in both hemispheres. Initially new infectious diseases caused precipitous declines in the numbers of indigenous peoples of the Americas. Traders returned to Europe with maize, potatoes, and tomatoes, which became very important crops in Europe by the 18th century, and later in Asia.

The term was first used in 1972 by American historian Alfred W. Crosby in his environmental history book The Columbian Exchange.[2] It was rapidly adopted by other historians and journalists and has become widely known.

Origin of the term

In 1972 Alfred W. Crosby, an American historian at the University of Texas at Austin, published The Columbian Exchange.[2] He published subsequent volumes within the same decade. His primary focus was mapping the biological and cultural transfers that occurred between the Old and New Worlds. He studied the effects of Columbus's voyages between the two – specifically, the global diffusion of crops, seeds, and plants from the New World to the Old, which radically transformed agriculture in both regions. His research made a lasting contribution to the way scholars understand the variety of contemporary ecosystems that arose due to these transfers.[3]

The term has become popular among historians and journalists and has since been enhanced with Crosby's later book in 3 editions, Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900–1900. Charles C. Mann, in his book 1493 further expands and updates Crosby's original research.[4]

Effects

Crops

Because of the new trading resulting from the Columbian exchange, several plants native to the Americas have spread around the world, including potatoes, maize, tomatoes, and tobacco.[5] Before 1500, potatoes were not grown outside of South America. By the 19th century, they were cultivated and consumed widely in Europe and had become important crops in both India and North America. Potatoes eventually became an important staple of the diet in much of Europe, contributing to an estimated 25% of the population growth in Afro-Eurasia between 1700 and 1900.[6] Many European rulers, including Frederick the Great of Prussia and Catherine the Great of Russia, encouraged the cultivation of the potato.[7]

Maize and cassava, introduced by the Portuguese from South America in the 16th century,[8] gradually replaced sorghum and millet as Africa's most important food crops.[9] Spanish colonizers of the 16th-century introduced new staple crops to Asia from the Americas, including maize and sweet potatoes, and thereby contributed to population growth in Asia.[10] On a larger scale, the introduction of potatoes and maize to the Old World "resulted in caloric and nutritional improvements over previously existing staples" throughout the Eurasian landmass,[11] enabling more varied and abundant food production.[12]

Tomatoes, which came to Europe from the New World via Spain, were initially prized in Italy mainly for their ornamental value. But starting in the 19th century, tomato sauces became typical of Neapolitan cuisine and, ultimately, Italian cuisine in general.[13] Coffee (introduced in the Americas circa 1720) from Africa and the Middle East and sugarcane (introduced from the Indian subcontinent) from the Spanish West Indies became the main export commodity crops of extensive Latin American plantations. Introduced to India by the Portuguese, chili and potatoes from South America have become an integral part of their cuisine.[14]

Rice

Rice was another crop that became widely cultivated during the Columbian exchange. As the demand in the New World grew, so did the knowledge of how to cultivate it. The two primary species used were Oryza glaberrima and Oryza sativa, originating from West Africa and Southeast Asia, respectively. Slaveholders in the New World relied upon the skills of enslaved Africans to cultivate both species.[15] The English colonies of Georgia and South Carolina were key places where rice was grown during the years of the slave trade, as were Spanish-controlled Caribbean islands such as Puerto Rico and Cuba. Enslaved Africans brought their knowledge of water control, milling, winnowing, and other general agrarian practices to the fields. This widespread knowledge amongst enslaved Africans eventually led to rice becoming a staple dietary item in the New World.[3][16]

Fruits

Citrus fruits and grapes were brought to the Americas from the Mediterranean. At first planters struggled to adapt these crops to the climates in the New World, but by the late 19th century they were cultivated more consistently.[17]

Bananas were introduced into the Americas in the 16th century by Portuguese sailors who came across the fruits in West Africa, while engaged in commercial ventures and the slave trade. Bananas were consumed in minimal amounts in the Americas as late as the 1880s. The U.S. did not see major increases in banana consumption until large plantations were established in the Caribbean.[18]

Tomatoes

It took three centuries after their introduction in Europe for tomatoes to become a widely accepted food item.

Tobacco, potatoes, chili peppers, tomatillos, and tomatoes are all members of the nightshade family. All of these plants bear such resemblance to the European nightshade that even an amateur could deduce that they were a kind of nightshade, just by simple observation of the flowers and berries. Similar to some European Nightshade varieties, tomatoes and potatoes can be harmful or even lethal, if the wrong part of the plant is consumed in the wrong quantity. Physicians, in the 16th-century, had good reason to be wary that this native Mexican fruit was poisonous; they suspected it of generating "melancholic humours".

In 1544, Pietro Andrea Mattioli, a Tuscan physician and botanist, suggested that tomatoes might be edible, but no record exists of anyone consuming them at this time. However, in 1592 the head gardener at the botanical garden of Aranjuez near Madrid, under the patronage of Philip II of Spain, wrote, "it is said [tomatoes] are good for sauces". In spite of these comments, tomatoes remained exotic plants grown for ornamental purposes, but rarely for culinary use.

On October 31, 1548, the tomato was given its first name anywhere in Europe when a house steward of Cosimo I de' Medici, Duke of Florence, wrote to the De' Medici's private secretary that the basket of pomi d'oro "had arrived safely". At this time, the label pomi d'oro was also used to refer to figs, melons, and citrus fruits in treatises by scientists.[19]

In the early years, tomatoes were mainly grown as ornamentals in Italy. For example, the Florentine aristocrat Giovan Vettorio Soderini wrote how they "were to be sought only for their beauty" and were grown only in gardens or flower beds. Tomatoes were grown in elite town and country gardens in the fifty years or so following their arrival in Europe, and were only occasionally depicted in works of art.

The practice of using tomato sauce with pasta developed only in the late nineteenth century. Of all the New World plants introduced to Italy, only the potato took as long as the tomato to gain acceptance as a food.

Today around 32,000 acres (13,000 ha) of tomatoes are cultivated in Italy. In some areas, relatively few tomatoes are grown and consumed.[19]

Livestock

Initially at least, the Columbian exchange of animals largely went in one direction, from Europe to the New World, as the Eurasian regions had domesticated many more animals. Horses, donkeys, mules, pigs, cattle, sheep, goats, chickens, large dogs, cats, and bees were rapidly adopted by native peoples for transport, food, and other uses.[20] One of the first European exports to the Americas, the horse, changed the lives of many Native American tribes. The mountain tribes shifted to a nomadic lifestyle, based on hunting bison on horseback. They largely gave up settled agriculture. Horse culture was adopted gradually by Great Plains Indians. The existing Plains tribes expanded their territories with horses, and the animals were considered so valuable that horse herds became a measure of wealth.[21]

The effects of the introduction of European livestock on the environments and peoples of the New World were not always positive. In the Caribbean, the proliferation of European animals consumed native fauna and undergrowth, changing habitat. If free ranging, the animals often damaged conucos, plots managed by indigenous peoples for subsistence.[22]

The Mapuche of Araucanía were fast to adopt the horse from the Spanish, and improve their military capabilities as they fought the Arauco War against Spanish colonizers.[23][24] Until the arrival of the Spanish, the Mapuches had largely maintained chilihueques (llamas) as livestock. The Spanish introduction of sheep caused some competition between the two domesticated species. Anecdotal evidence of the mid-17th century show that by then both species coexisted but that the sheep far outnumbered the llamas. The decline of llamas reached a point in the late 18th century when only the Mapuche from Mariquina and Huequén next to Angol raised the animal.[25] In the Chiloé Archipelago the introduction of pigs by the Spanish proved a success. They could feed on the abundant shellfish and algae exposed by the large tides.[25]

Disease

Before regular communication had been established between the two hemispheres, the varieties of infectious diseases that spread to humans, such as smallpox, were substantially more numerous in the Old World than in the New. The geography enabled extensive travel and trade between the East and West. Many diseases had migrated west across Eurasia with animals or people, or were brought by traders from Asia. While Europeans and Asians were affected by the Eurasian diseases, their endemic status in those continents over centuries resulted in many people gaining some immunity.

Old World diseases carried by Europeans had a devastating effect in the New World, as the native people in the Americas had no natural immunity to them. Measles caused many deaths. The smallpox epidemics are believed to have caused the largest death tolls among Native Americans, surpassing any wars[26] and far exceeding the comparative loss of life in Europe due to the Black Death.[1]:164

It is estimated that upwards of 80–95 percent of the Native American population died in these epidemics within the first 100–150 years following 1492. Many regions in the Americas lost 100% of their indigenous population.[1]:165 The beginning of demographic collapse on the North American continent has typically been attributed to the spread of a well-documented smallpox epidemic from Hispaniola in December 1518.[22] At that point approximately only 10,000 indigenous people were still alive on Hispaniola.[22]

European exploration of tropical areas was aided by the New World discovery of quinine, the first effective treatment for malaria. Europeans suffered from this disease, but some indigenous populations had developed at least partial resistance to it. In Africa, resistance to malaria has been associated with other genetic changes among sub-Saharan Africans and their descendants, which can cause sickle-cell disease.[1]:164 The resistance of sub-Saharan Africans to malaria in the southern United States and the Caribbean contributed greatly to the specific character of the Africa-sourced slavery in those regions.[27]

Similarly, yellow fever is thought to have been brought to the Americas from Africa via the Atlantic slave trade. Because it was endemic in Africa, many people there had acquired immunity. Europeans suffered higher rates of death than did African-descended persons when exposed to yellow fever in Africa and the Americas, where numerous epidemics swept the colonies beginning in the 17th century and continuing into the late 19th century. The disease caused widespread fatalities in the Caribbean during the heyday of slave-based sugar plantation.[22] The replacement of native forests by sugar plantations and factories facilitated its spread in the tropical area by reducing the number of potential natural mosquito predators.[22] The means of yellow fever transmission was unknown until 1881, when Carlos Finlay suggested that the disease was transmitted through mosquitoes, now known to be female mosquitoes of the species Aedes aegypti.[22]

The history of syphilis has been well-studied, but the exact origin of the disease is unknown and remains a subject of debate.[28] There are two primary hypotheses: one proposes that syphilis was carried to Europe from the Americas by the crew of Christopher Columbus in the early 1490s, while the other proposes that syphilis previously existed in Europe but went unrecognized.[29] These are referred to as the "Columbian" and "pre-Columbian" hypotheses.[29]

The first written descriptions of the disease in the Old World came in 1493.[30] The first large outbreak of syphilis in Europe occurred in 1494/1495 in Naples, Italy, among the army of Charles VIII, during its invasion of Naples.[29][31][32][33] Many of the crew members who had served on the voyage had joined this army. After the victory, Charles's largely mercenary army returned to their respective homes, thereby spreading "the Great Pox" across Europe and triggering the deaths of more than five million people.[34][35]

Cultural exchanges

One of the results of the movement of people between New and Old Worlds were cultural exchanges. For example, in the article "The Myth of Early Globalization: The Atlantic Economy, 1500–1800", Pieter Emmer makes the point that "from 1500 onward, a 'clash of cultures' had begun in the Atlantic".[36] This clash of culture involved the transfer of European values to indigenous cultures. As an example, the emergence of the concept of private property in regions where property was often viewed as communal, concepts of monogamy (although many indigenous peoples were already monogamous,) the role of women and children in the social system, and the "superiority of free labor,"[37] although slavery was already a well-established practice among many indigenous peoples. Another example included the European deprecation of human sacrifice, an established religious practice among some indigenous populations.

When European colonizers first entered North America, they encountered fence-less lands. They believed that the land was unimproved and available for their taking, as they sought economic opportunity and homesteads. But when the English entered Virginia, they encountered a fully established culture of people called the Powhatan. The Powhatan farmers in Virginia scattered their farm plots within larger cleared areas. These larger cleared areas were a communal place for growing useful plants. As the Europeans viewed fences as hallmarks of civilization, they set about transforming "the land into something more suitable for themselves".[38]

Tobacco was a New World agricultural product, originally a luxury good spread as part of the Columbian exchange. As is discussed in regard to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the tobacco trade increased demand for free labor and spread tobacco worldwide. In discussing the widespread uses of tobacco, the Spanish physician Nicolas Monardes (1493–1588) noted that "The black people that have gone from these parts to the Indies, have taken up the same manner and use of tobacco that the Indians have".[39] As Europeans traveled to other parts of the world, they took with them the practices related to tobacco. Demand for tobacco grew in the course of these cultural exchanges among peoples.

One of the most clearly notable areas of cultural clash and exchange was that of religion, often the lead point of cultural conversion. In the Spanish and Portuguese dominions, the spread of Catholicism, steeped in a European values system, was a major objective of colonization. Europeans often pursued it via explicit policies of suppression of indigenous languages, cultures and religions. In English North America, missionaries converted many tribes and peoples to Protestant faiths. The French colonies had a more outright religious mandate, as some of the early explorers, such as Jacques Marquette, were also Catholic priests. In time, and given the European technological and immunological superiority which aided and secured their dominance, indigenous religions declined in the centuries following the European settlement of the Americas.

While Mapuche people did adopt the horse, sheep, and wheat, the over-all scant adoption of Spanish technology by Mapuche has been characterized as a means of cultural resistance.[23]

According to Caroline Dodds Pennock, in Atlantic history indigenous people are often seen as static recipients of transatlantic encounters. But thousands of Native Americans crossed the ocean during the sixteenth century, some by choice.[40]

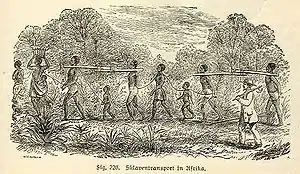

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade was the transfer of Africans primarily from West Africa to parts of the Americas between the 16th and 19th centuries, a large part of the Columbian Exchange.[41] About 10 million Africans arrived in the Americas on European boats as slaves. The journey that enslaved-Africans took from parts of Africa to America is commonly known as the "middle passage".[42] Today, millions of people in North America and South America, including the vast majority of the populations in the countries of the Caribbean, are descended from these Africans brought to the New World by Europeans. Slavery was already widespread in Africa, where captives were taken in war.

Enslaved Africans helped shape an emerging African-American culture in the New World. They participated in both skilled and unskilled labor. Their descendants gradually developed an ethnicity that drew from the numerous African tribes as well as European nationalities, and they created a new culture.[41]

The treatment of enslaved Africans during the Atlantic slave trade became one of the most controversial topics in the history of the New World. Slavery was abolished in 1865 in the United States and was ended in Brazil in 1888. Its effects and legacy have been key subjects in politics, pop culture and media.

Organism examples

| Type of organism | Old World to New World | New World to Old World |

|---|---|---|

| Domesticated animals |

|

|

| Cultivated plants |

|

|

| Cultivated fungi |

|

|

| Infectious diseases |

|

Later history

Plants that arrived by land, sea, or air in the times before 1492 are called archaeophytes, and plants introduced to Europe after those times are called neophytes. Invasive species of plants and pathogens also were introduced by chance, including such weeds as tumbleweeds (Salsola spp.) and wild oats (Avena fatua). Some plants introduced intentionally, such as the kudzu vine introduced in 1894 from Japan to the United States to help control soil erosion, have since been found to be invasive pests in the new environment.

Fungi have also been transported, such as the one responsible for Dutch elm disease, killing American elms in North American forests and cities, where many had been planted as street trees. Some of the invasive species have become serious ecosystem and economic problems after establishing in the New World environments.[43][44] A beneficial, although probably unintentional, introduction is Saccharomyces eubayanus, the yeast responsible for lager beer now thought to have originated in Patagonia.[45] Others have crossed the Atlantic to Europe and have changed the course of history. In the 1840s, Phytophthora infestans crossed the oceans, damaging the potato crop in several European nations. In Ireland, the potato crop was totally destroyed; the Great Famine of Ireland caused millions to starve to death or emigrate.

In addition to these, many animals were introduced to new habitats on the other side of the world either accidentally or incidentally. These include such animals as brown rats, earthworms (apparently absent from parts of the pre-Columbian New World), and zebra mussels, which arrived on ships.[46] Escaped and feral populations of non-indigenous animals have thrived in both the Old and New Worlds, often negatively impacting or displacing native species. In the New World, populations of feral European cats, pigs, horses, and cattle are common, and the Burmese python and green iguana are considered problematic in Florida. In the Old World, the Eastern gray squirrel has been particularly successful in colonising Great Britain, and populations of raccoons can now be found in some regions of Germany, the Caucasus, and Japan. Fur farm escapees such as coypu and American mink have extensive populations.

See also

- Alfred W. Crosby

- Arab Agricultural Revolution

- Domestication

- Great American Interchange

- Glossary of invasion biology terms

- Guns, Germs, and Steel

- Indian Givers: How the Indians of the Americas Transformed the World

- List of food plants native to the Americas

- Population history of indigenous peoples of the Americas

- Pre-Columbian trans-oceanic contact theories

- Transformation of culture

- 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created

- 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

References

- Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2010). "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 24 (2): 163–188. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.232.9242. doi:10.1257/jep.24.2.163. JSTOR 25703506.

- Gambino, Megan (October 4, 2011). "Alfred W. Crosby on the Columbian Exchange". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- Carney, Judith (2001). Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas. United States of America: Harvard University Press. pp. 4–5.

- de Vorsey, Louis (2001). "The Tragedy of the Columbian Exchange". In McIlwraith, Thomas F.; Muller, Edward K. (eds.). North America: The Historical Geography of a Changing Continent. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. p. 27.

Thanks to…Crosby's work, the term 'Columbian exchange' is now widely used…

- Ley, Willy (December 1965). "The Healthfull Aromatick Herbe". For Your Information. Galaxy Science Fiction. pp. 88–98.

- Nathan, Nunn; Nancy, Qian (2011). "The Potato's Contribution to Population and Urbanization: Evidence from a Historical Experiment". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2: 593–650.

- Crosby, Alfred (2003). The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. p. 184.

- "Super-Sized Cassava Plants May Help Fight Hunger In Africa" Archived December 8, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, The Ohio State University

- "Maize Streak Virus-Resistant Transgenic Maize: an African solution to an African Problem", Scitizen, August 7, 2007

- "China's Population: Readings and Maps", Columbia University, East Asian Curriculum Project

- Nathan, Nunn; Nancy, Qian (2010). "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food and Ideas" (PDF). Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2: 163–88, 167. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 11, 2017. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2003). The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Praeger. p. 177.

- Riley, Gillian, ed. (2007). "Tomato". The Oxford Companion to Italian Food. Oxford University Press. pp. 529–530. ISBN 978-0-19-860617-8.

- Collingham, Lizzie (2006). "Vindaloo: the Portuguese and the chili pepper". Curry: A Tale of Cooks and Conquerors. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 47–73. ISBN 978-0-19-988381-3.

- Carney, Judith A. (2001). "African Rice in the Columbian Exchange". The Journal of African History. 42 (3): 377–396. doi:10.1017/s0021853701007940. JSTOR 3647168. PMID 18551802.

- Knapp, Seaman Ashahel (1900). Rice culture in the United States (Public domain ed.). U.S. Department of Agriculture. pp. 6–.

- McNeill, J.R. "The Columbian Exchange". NCpedia. State Library of North Carolina. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- Gibson, Arthur. "Bananas & Plantains". University of California, Los Angeles. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012.

- A History of the Tomato in Italy Pomodoro!, David Gentilcore (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2010).

- Michael Francis, John, ed. (2006). "Columbian Exchange—Livestock". Iberia and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History: a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 303–308. ISBN 978-1-85109-421-9.

- This transfer reintroduced horses to the Americas, as the species had died out there prior to the development of the modern horse in Eurasia.

- Palmié, Stephan (2011). The Caribbean: A History of the Region and Its Peoples. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226645087.

- Dillehay, Tom D. (2014). "Archaeological Material Manifestations". In Dillehay, Tom (ed.). The Teleoscopic Polity. Springer. pp. 101–121. ISBN 978-3-319-03128-6.

- Bengoa, José (2003). Historia de los antiguos mapuches del sur (in Spanish). Santiago: Catalonia. pp. 250–251. ISBN 978-956-8303-02-0.

- Torrejón, Fernando; Cisternas, Marco; Araneda, Alberto (2004). "Efectos ambientales de la colonización española desde el río Maullín al archipiélago de Chiloé, sur de Chile" [Environmental effects of the Spanish colonization from de Maullín river to the Chiloé archipelago, southern Chile]. Revista Chilena de Historia Natural (in Spanish). 77 (4): 661–677. doi:10.4067/s0716-078x2004000400009.

- "The Story Of... Smallpox – and other Deadly Eurasian Germs", Guns, Germs and Steel, PBS Archived August 26, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Esposito, Elena (Summer 2015). "Side Effects of Immunities: the African Slave Trade" (PDF). European University Institute.

- Kent ME, Romanelli F (February 2008). "Reexamining syphilis: an update on epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and management". Ann Pharmacother. 42 (2): 226–36. doi:10.1345/aph.1K086. PMID 18212261. S2CID 23899851.

- Farhi, D; Dupin, N (September–October 2010). "Origins of syphilis and management in the immunocompetent patient: facts and controversies". Clinics in Dermatology. 28 (5): 533–8. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.03.011. PMID 20797514.

- Smith, Tara C. (December 23, 2015). "Thanks Columbus! The true story of how syphilis spread to Europe". Quartz. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

The first cases of the disease in the Old World were described in 1493.

- Franzen, C. (December 2008). "Syphilis in composers and musicians—Mozart, Beethoven, Paganini, Schubert, Schumann, Smetana". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases. 27 (12): 1151–1157. doi:10.1007/s10096-008-0571-x. PMID 18592279. S2CID 947291.

- A New Skeleton and an Old Debate About Syphilis; The Atlantic; Cari Romm; February 18, 2016

- Choi, Charles Q. (December 27, 2011). "Case Closed? Columbus Introduced Syphilis to Europe". Scientific American. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- CBC News Staff (January 2008). "Study traces origins of syphilis in Europe to New World". Archived from the original on June 7, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- Harper, Kristin; et al. (January 2008). "On the Origin of the Treponematoses: A Phylogenetic Approach". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2 (1): e148. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000148. PMC 2217670. PMID 18235852.

- Emmer, Pieter. "The Myth of Early Globalization: The Atlantic Economy, 1500–1800". European Review 11, no. 1. Feb. 2003. p. 45–46

- Emmer, Pieter. "The Myth of Early Globalization: The Atlantic Economy, 1500–1800". European Review 11, no. 1. Feb. 2003. p. 46

- Mann, Charles. 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. New York, New York: Vintage Books, 2011. loc. 1094 and 1050

- Monardes, Nicholas. "Of the Tabaco and of his Greate Vertues". Frampton, John trans, Wolf, Michael, ed. Tobacco.org. Accessed June 1, 2017 http://archive.tobacco.org/History/monardes.html Archived June 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Pennock, Caroline (June 1, 2020). "Aztecs Abroad? Uncovering the Early Indigenous Atlantic". The American Historical Review. 125 (3): 787–814. doi:10.1093/ahr/rhaa237. ISSN 0002-8762.

- Carney, Judith (2001). Black Rice. Harvard University Press. pp. 2–8.

- Gates, Louis. "100 Amazing Facts About the Negro". PBS. WNET. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- Simberloff, Daniel (2000). "Introduced Species: The Threat to Biodiversity & What Can Be Done". American Institute of Biological Sciences: Bringing Biology to Informed Decision Making.

- Fernández Pérez, Joaquin and Ignacio González Tascón (eds.) (1991). La agricultura viajera. Barcelona, Spain: Lunwerg Editores, S. A.

- Elusive Lager Yeast Found in Patagonia, Discovery News, August 23, 2011

- Hoddle, M. S. "Quagga & Zebra Mussels". Center for Invasive Species Research, University of California, Riverside . Retrieved June 29, 2010.

External links

- The Columbian Exchange: Plants, Animals, and Disease between the Old and New Worlds by Alfred W. Crosby (2009)

- Worlds Together, Worlds Apart by Jeremy Adelman, Stephen Aron, Stephen Kotkin, et al.

- Foods that Changed the World by Steven R. King from the Wayback Machine

- The Columbian Exchange video, study guide, analysis, and teaching guide

.svg.png.webp)