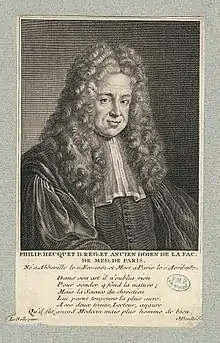

Philippe Hecquet

Philippe Hecquet (February 11, 1661 - April 11, 1737) was a French physician and vegetarianism activist.

Philippe Hecquet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | February 11, 1661 |

| Died | April 11, 1737 |

| Occupation | Physician, writer |

Biography

Hecquet obtained his M.D. from Reims in 1684.[1] In 1688, he moved to Port-Royal-des-Champs, where he succeeded Jean Hamon, as physician.[2] He spent much time helping the poor. In 1697, he became Doctor at University of Paris and received the official hat after an examination of "rare success".[2] The Faculty named him Docteur-Régent and he was appointed as Professor of Materia Medica. In 1712, he was named Dean of the Faculty.[2]

Hecquet was an ascetic, Cartesian mechanist and vegetarian.[3] He was influenced by Porphyry. Hecquet was concerned with health from a diet perspective and campaigned against the consumption of meat, stating it interfered with digestion and circulation of the blood.[3] Hecquet noted how the rich often consumed much expensive meat, spicy sauces and strong wine which was bad for health.[4] He argued that such a diet was difficult for the body to digest and impaired the elasticity of the fluid-bearing organs.[4] He stated that if flesh was to be eaten it should only be fish.[4] He believed that fruits, grains, nuts and seeds should replace meat. Hecquet was a Jansenist Catholic and promoted a "theological medicine".[5] He argued that the Garden of Eden depicted a vegetarian regime.[3]

Hecquet argued that all physiological processes could be reduced to simple mechanisms. He developed a digestive theory of "trituration" which emphasized the grinding action of mastication and peristalsis of muscle walls of the stomach.[6] Hecquet believed fish and vegetables are superior to meat because their composition is easily broken down by trituration.[6]

Hecquet has been described as "one of the first systematic proponents of vegetarianism".[7] Historian Ken Albala credits Hecquet for making the first scientific defense of a vegetarian diet.[8]

Selected publications

- Traité de dispenses du Careme (1710)

- La Médecine, la Chirurgie, et la Pharmacie des Pauvres (1740-1742)

- La Brigandage de la Médecine (1755)

See also

References

- Osler, William. (1987). Bibliotheca Osleriana: A Catalogue of Books Illustrating the History of Medicine and Science Collected, Arranged, and Annotated. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 262

- Williams, Howard. (1896). The Ethics of Diet. London. pp. 314-318

- Preece, Rod. (2008). Sins of the Flesh: A History of Ethical Vegetarian Thought. UBC Press. p. 177. ISBN 978-0-7748-15093

- L. W. B. Brockliss. (1989). The Medico-Religious Universe of an Early Eighteenth-Century Parisian Doctor: The Case Philippe Hecquet. In Roger French; Andrew Wear. The Medical Revolution of the Seventeenth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 202. ISBN 0-521-35510-9

- Puskar-Pasewicz, Margaret. (2010). Cultural Encyclopedia of Vegetarianism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 106. ISBN 978-0-313-37556-9

- Albala, Ken; Eden, Trudy. (2011). Food and Faith in Christian Culture. Columbia University Press. pp. 116-118. ISBN 978-0-231-52079-9

- Moulin, Léo. (2002). Eating and Drinking in Europe: A Cultural History. Mercatorfonds. p. 54

- Albala, Ken. (2009). The First Scientific Defense of a Vegetarian Diet. In Susan R. Friedland. Vegetables: Proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cooking 2008. Prospect Books. pp. 29-35. ISBN 978-1-903018-66-8