Plastic milk container

Plastic milk containers are plastic containers for storing, shipping and dispensing milk. Plastic bottles, sometimes called jugs, have largely replaced glass bottles for home consumption. Glass milk bottles have traditionally been reusable while light-weight plastic bottles are designed for single trips and plastic recycling.

Materials

Packaging of milk is regulated by regional authorities. Use of Food contact materials is required: potential food contamination is prohibited. Strict standards of cleanliness and processing must be followed.

The most common material in milk packaging is high density polyethylene (HDPE), recycling code 2. Low density polyethylene (LDPE), and polyester (PET),[1] are also in use. Polycarbonate had been considered but had concerns about potential contamination with Bisphenol A.[2]

Container forms

Blow molded plastic milk bottles have been in use since the 1960s.[3] [4] [5] HDPE is the primary material but polyester is also used. A wide variety of milk bottle designs are available. Some have a round cross section while others have a more square or rectangular shape. A special flat-top square milk jug was recently developed to maximize shipping and storing efficiency but had some difficulties in dispensing. Many milk bottles have integral handles.

Milk bags are also in use. The milk is sold in a plastic bag and put into a pitcher for use.

Small individual containers of milk and cream are often thermoformed or injection molded and have a peelable lid. These are often used in restaurants.

Shelf life

The shelf life of pasteurized milk in HDPE bottles and LDPE pouches has been determined to be between 10 and 21 days when stored at 4-8 °C. Other factors such as light and temperature abuse have effects. Shelf life can be extended by ultrapasteurisation and aseptic processing.[6] [7]

Volume control

Milk containers for retail sale must contain the same amount of milk as indicated on the label. To be acceptable to consumers, the containers must also appear to be completely full. Therefore, the volume of the container must be precisely controlled.

The designer of a die for a blow moulded bottle can never be completely sure of how much the finished bottle will hold. Shrinkage always occurs after the item is released from the mould. The amount of shrinkage depends upon many factors, including cycle time, inflation air pressure, time in storage prior to filling, storage temperature, and more.

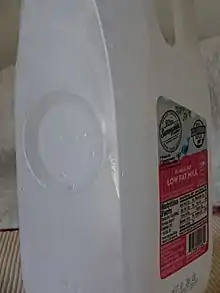

A volume adjuster insert is one way to slightly adjust the volume of a bottle, without building a completely new mould. A volume insert attaches to the inside of a mould, creating a circular indentation on the side of the finished bottle. Different size inserts can be used as manufacturing circumstances change, for example mould temperature or cooling rate. The volume of finished bottles is periodically measured, and volume inserts are changed as needed.[8]

Environmental comparisons

Many potential factors are involved in environmental comparisons of returnable vs non-returnable systems. Researchers have often used life cycle analysis methodologies to balance the many diverse considerations. Often the comparisons show benefits and problems with all alternatives.[9] [10]

Reuse of bottles requires a reverse logistics system, cleaning and, sanitizing bottles, and an effective Quality Management System. A key factor with glass milk bottles is the number of cycles of uses to be expected. Breakage, contamination, or other loss reduces the benefits of returnables. A key factor with one-way recyclables is the recycling rate: In the US, only about 30-35% of HDPE bottles are recycled.[11]

Examples

.jpg.webp) Individual plastic container of coffee creamer, Japan

Individual plastic container of coffee creamer, Japan 11.5 fl oz, 340 mL, PETE bottle

11.5 fl oz, 340 mL, PETE bottle Plastic Bags of Milk

Plastic Bags of Milk 1.4 L, 48 fl oz PETE bottle

1.4 L, 48 fl oz PETE bottle Flat-top square jug

Flat-top square jug HDPE milk bottle, 40 fl oz, 1 1/4 quart

HDPE milk bottle, 40 fl oz, 1 1/4 quart

See also

- Gallon smashing, internet challenge involving participants deliberately spilling milk in a supermarket by breaking containers

References

- Sidel (18 August 2018), "Many Good Reasons for Liquid Dairy to Switch to PET Packaging", Canadian Packaging, retrieved 16 September 2020

- Carwile, J L (2009). "Polycarbonate Bottle Use and Urinary Bisphenol A Concentrations". Environ Health Perspect. 117 (9): 1368–1372. doi:10.1289/ehp.0900604. PMC 2737011. PMID 19750099.

- US3225950A, Josephsen, "Plastic bottle", published 1965

- US3152710A, Platte, "Plastic milk bottle", published 1964

- US3397724A, Bolen, "Thin-walled container and method of making the same", published 1966

- Galic, K (August 2018), "Packaging materials and methods for dairy applications", New Food, retrieved 11 September 2019

- Petrus, R R (2010). "Microbiological Shelf Life of Pasteurized Milk in Bottle and Pouch". Journal of Food Science. 75 (1): M36-40. doi:10.1111/j.1750-3841.2009.01443.x. PMID 20492183. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

- Lauren Joshi (June 2017). "Understanding Dairy Bottle Shrinkage" (PDF). Qenos. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- Van Doorsselaer, K; Fox (2000), "Estimation of the energy needs in life cycle analysis of one-way and returnable glass packaging", Packaging Technology and Science, 12 (5): 235–239, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1522(199909/10)12:5<235::AID-PTS474>3.0.CO;2-W

- Spitzly, David (1997), Life Cycle Design of Milk and Juice Packaging (PDF), U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, retrieved 29 June 2014

- "2016 United States National Postconsumer Plastic Bottle Recycling Report" (PDF). Association of Plastic Rcyclers. 2017. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

Books, general references

- Yam, K.L., "Encyclopedia of Packaging Technology", John Wiley & Sons, 2009, ISBN 978-0-470-08704-6