Kefir

Kefir or kephir (/kəˈfɪər/ kə-FEER),[2][3] is a fermented milk drink similar to a thin yogurt or ayran that is made from kefir grains, a specific type of mesophilic symbiotic culture. The drink originated in the North Caucasus, in particular the Elbrus environs along the upper Kuban river region of Karachay and Balkaria from where it came to Russia,[4][5] and from there it spread to Europe and the United States, where it is prepared by inoculating cow, goat, or sheep milk with kefir grains.[6]

Plain milk kefir being poured | |

| Alternative names | Milk kefir, gıpı ayran, qundəps, búlgaros |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Karachay and Balkaria[1] |

| Region or state | North Caucasus |

| Main ingredients | Milk, kefir grains |

Origin and etymology

The word kefir, known in the Russian language (кефир) since at least 1884,[7] is of Turkic and North Caucasian origin,[8][9] and comes ultimately from Old Turkic köpür '(milk) froth, foam' and köpürmäk 'to froth'.[9] Some sources see a connection to kaf, a Kurdish (kef) or Persian (کف) word meaning foam or bubbles.[10] Traditional kefir was made in goatskin bags that were hung near a doorway; the bags would be knocked by anyone passing through to keep the milk and kefir grains well mixed.[11]

In Karachay-Balkar it is called gıpı, which has connection with gıbıt (wineskin). It was under the name "wineskin" that Karachay kefir was distributed in the second half of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century.[12][13] Kefir spread from the former Soviet Union to the rest of Europe, Japan, and the United States by the early 21st century.[8][14][15]

Among people of Circassian descent, it is called qundəps (Adyghe: къундэпс, Adyghe pronunciation: [qwəndaps]).[16] It has become known in parts of Latin America as búlgaros, or "Bulgarians".

The homeland of kefir is considered to be "the vicinity of Elbrus along the upper reaches of the Kuban",[4] and the invention of kefir sourdough belongs to Karachays and Balkars.[17][18]

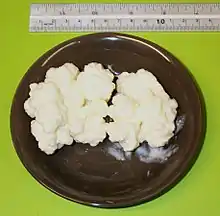

The cauliflower-like grains of Kefir culture were thought of as having amazing healing powers as far back as the 18th century, and great care was taken by the Karachay families who bequeathed from generation to generation as a source of family wealth. It's still believed in Karachay tradition that it's taboo to give kefir grains to anyone because it makes gıpı spirits angry. So Karachay people found a way to get kefir grains, they ″bogusly steal″ them from their neighbors by prior agreement, so spirits wouldn't know about this. [19] Word of this powerful food and medicine spread to areas far from the Caucasus, and at the beginning of this century, the All-Russian Physician’s Society asked two brothers Blandov, who owned cheese manufacturing factories in the Northern Caucasus, for help in obtaining the culture grains of Kefir. One of the brothers, Nikolai Blandov, persuaded a young employee, Irina Timofeevna Sakharova, to use her beauty to gain access to the much-desired grain. She, therefore, traveled to the Narsana where she attempted to interest a local Karachay uzden, Bek-Mirza Baychorov, to assist her in this plot. When he declined to give up any of the precious substance she left to return back, only to be captured by agents of the Bek-Mirza, who didn't want to give up the kefir and did not wish to lose the presence of the lovely Irina either.[20] Finding herself back in his presence and facing a proposal of marriage into the bargain she remained silent until a rescue mission arranged by her employers freed her. She promptly brought the prince before the Tsar’s court where she accepted grains of Kefir as the settlement of her suit for abduction. In September 1908 Irina Sakharova brought the first bottles of Kefir to Moscow for sale where it was at first used for medicinal purposes. In 1973, Irina, then 85, was sent a letter from the Minister of the Food Industry of The Soviet Union, acknowledging her great part in bringing Kefir to the Russian people.[21] Also, according to Alimurat Tekeyev (great-grandson of Bek-Mirza Baychorov, owner of a patent for the manufacture of ayran), letters from Irina Timofeevna refute the fact of abduction: "My great-grandfather, realizing what would become the most valuable gift for Irina, gifted kefir fungi to her". Then Irina Timofeevna wrote: “Bek-Mirza and I left the world a huge health-improving heritage of millions. If Bek-Mirza is no longer with us - his eternal memory ”.In fact, Bekmyrza Baichorov continued to engage in animal husbandry and supplied the Karachay breed of sheep for the famous Parisian Maxim restaurant, as well as to restaurants of Moscow.[22][23]

Fermentation

Traditional kefir is fermented at ambient temperatures, generally overnight. Fermentation of the lactose yields a sour, carbonated, slightly alcoholic beverage, with a consistency and taste similar to drinkable yogurt.[24]

The kefir grains initiating the fermentation are initially created by auto-aggregations of Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens and Saccharomyces turicensis, which then gets the surface adhered by multiple biofilm producers to become a three dimensional microcolony.[25][26] The biofilm is a matrix of heteropolysaccharides called kefiran, which is composed of equal proportions of glucose and galactose.[8] It resembles small cauliflower grains, with color ranging from white to creamy yellow. A complex and highly variable symbiotic community can be found in these grains, which can include acetic acid bacteria (such as A. aceti and A. rasens), yeasts (such as Candida kefyr and S. cerevisiae) and a number of Lactobacillus species, such as L. parakefiri, L. kefiranofaciens (and subsp. kefirgranum[27]), L. kefiri,[28] etc.[8] While some microbes predominate, Lactobacillus species are always present.[29] The microbe flora can vary between batches of kefir due to factors such as the kefir grains rising out of the milk while fermenting or curds forming around the grains, as well as temperature.[30] Additionally, Tibetan kefir composition differs from that of the Russian kefir, Irish kefir, Taiwan kefir and Turkey fermented beverage with kefir.[8] In recent years, the use of freeze-dried starter culture has become common due to stability of the fermentation result, because the species of microbes are selected in laboratory conditions, as well as easy transportation.[31][32][33]

During fermentation, changes in the composition of ingredients occur. Lactose, the sugar present in milk, is broken down mostly to lactic acid (25%) by the lactic acid bacteria, which results in acidification of the product.[29] Propionibacteria further break down some of the lactic acid into propionic acid (these bacteria also carry out the same fermentation in Swiss cheese). Other substances that contribute to the flavor of kefir are pyruvic acid, acetic acid, diacetyl and acetoin (both of which contribute a "buttery" flavor), citric acid, acetaldehyde, and amino acids resulting from protein breakdown.[34]

Low lactose content

The slow-acting yeasts, late in the fermentation process, break lactose down into ethanol and carbon dioxide. As a result of the fermentation, very little lactose remains in kefir. People with lactose intolerance are able to tolerate kefir, provided the number of live bacteria present in this beverage consumed is high enough (i.e., fermentation has proceeded for adequate time). It has also been shown that fermented milk products have a slower transit time than milk, which may further improve lactose digestion.[35]

Alcohol/ethanol content

Kefir contains ethanol,[36] which is detectable in the blood of human consumers.[37] The level of ethanol in kefir can vary by production method. A 2016 study of kefir sold in Germany showed an ethanol level of only 0.02 g per litre, which was attributed to fermentation under controlled conditions allowing the growth of Lactobacteria only, but excluding the growth of other microorganisms that form much higher amounts of ethanol.[38] A 2008 study of German commercial kefir found levels of 0.002-0.005% of ethanol.[39] Kefir produced by small-scale dairies in Russia early in the 20th century had 1-2% ethanol.[39] Modern processes, which use shorter fermentation times, result in much lower ethanol concentrations of 0.2–0.3%.

Nutrition

Composition

Kefir products contain nutrients in varying amounts from negligible to significant, including dietary minerals, vitamins, essential amino acids, and conjugated linoleic acid,[40] in amounts similar to unfermented cow, goat, or sheep milk.[41] At a pH of 4.2 - 4.6,[42] kefir is composed mainly of water and by-products of the fermentation process, including carbon dioxide and ethanol.[43]

Typical of milk, several dietary minerals are found in kefir, such as calcium, iron, phosphorus, magnesium, potassium, sodium, copper, molybdenum, manganese, and zinc in amounts that have not been standardized to a reputable nutrient database.[43] Also similar to milk,[41] kefir contains vitamins in variable amounts, including vitamin A, vitamin B1 (thiamine), vitamin B2 (riboflavin), vitamin B3 (niacin), vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), vitamin B9 (folic acid), vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin), vitamin C, vitamin D, and vitamin E.[43] Essential amino acids found in kefir include methionine, cysteine, tryptophan, phenylalanine, tyrosine, leucine, isoleucine, threonine, lysine, and valine,[43] as for any milk product.[41]

Microbiota

Probiotic bacteria found in kefir products include: Lactobacillus acidophilus, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Streptococcus thermophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, Lactobacillus helveticus, Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens, Lactococcus lactis, and Leuconostoc species.[29][40][44] Lactobacilli in kefir may exist in concentrations varying from approximately 1 million to 1 billion colony-forming units per milliliter, and are the bacteria responsible for the synthesis of the polysaccharide kefiran.[6]

In addition to bacteria, kefir often contains strains of yeast that can metabolize lactose, such as Kluyveromyces marxianus, Kluyveromyces lactis, and Saccharomyces fragilis, as well as strains of yeast that do not metabolize lactose, including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Torulaspora delbrueckii, and Kazachstania unispora.[29] The nutritional significance of these strains is unknown.

Production

Kefir is made by adding kefir grains to milk typically at a proportion of 2–5% grains-to-milk. The mixture is then placed in a corrosion-resistant container, such as a glass jar, and stored preferably in the dark to prevent degradation of light-sensitive vitamins. After a period between 12–24 hours of fermentation at mild temperature, ideally 20–25 °C (68–77 °F),[34] the grains are strained from the milk using a corrosion-resistant (stainless steel or plastic) utensil and kept to produce another batch. During the fermentation process the grains enlarge and eventually split forming new units.

The resulting fermented liquid may be drunk, used in recipes, or kept aside in a sealed container for additional time to undergo a secondary fermentation. Because of its acidity the beverage should not be stored in reactive metal containers such as aluminium, copper, or zinc, as these may leach into it over time. The shelf life, unrefrigerated, is up to thirty days.[45]

The Russian method permits production of kefir on a larger scale and uses two fermentations. The first step is to prepare the cultures by inoculating milk with 2–3% grains as described. The grains are then removed by filtration and 1–3% of the resulting liquid mother culture is added to milk and fermented for 12 to 18 hours.[46]

Kefir can be made using freeze-dried cultures commonly available in powder form from health food stores. A portion of the resulting kefir can be saved to be used a number of times to propagate further fermentations but ultimately does not form grains.

In Taiwan, researchers were able to produce kefir in laboratory using microorganisms isolated from kefir grains. They report that the resulting kefir drink had chemical properties similar to homemade kefir.[47]

Milk types

Kefir grains will ferment the milk from most mammals and will continue to grow in such milk. Typical animal milks used include cow, goat, and sheep, each with varying organoleptic (flavor, aroma, and texture) and nutritional qualities. Raw milk has been traditionally used.

Kefir grains will also ferment milk substitutes such as soy milk, rice milk, nut milk and coconut milk, as well as other sugary liquids including fruit juice, coconut water, beer wort, and ginger beer. However, the kefir grains may cease growing if the medium used does not contain all the growth factors required by the bacteria.

Milk sugar is not essential for the synthesis of the polysaccharide that makes up the grains (kefiran), and rice hydrolysate is a suitable alternative medium.[48] Additionally, kefir grains will reproduce when fermenting soy milk, although they will change in appearance and size due to the differing proteins available to them.[49]

A variation of kefir grains that thrive in sugary water also exists, see water kefir (or tibicos), and can vary markedly from milk kefir in both appearance and microbial composition.

Culinary

As it contains Lactobacillus bacteria, kefir can be used to make a sourdough bread. It is also useful as a buttermilk substitute in baking. Kefir is one of the main ingredients in borscht in Lithuania, also known in Poland as Lithuanian cold soup (chłodnik litewski), and other countries. Kefir-based soup okroshka is common across the former Soviet Union. Kefir may be used in place of milk on cereal, granola, milkshakes, salad dressing, ice cream, smoothies and soup.

See also

Other fermented dairy products

Other fermented beverages

References

- "KEFIR – Ecosaving.net – EU GREEN REVOLUTION". 2020-04-05. Archived from the original on 2020-04-05. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- "kefir". Oxford Dictionaries.

- kefir. dictionary.reference.com

- Мусаевич, Мизиев, Исмаил (2010-03-07). История Балкарии и Карачая в трудах Исмаила Мизиева: В 3 т. (in Russian). Нальчик: Издательство М. и В. Котляровых. ISBN 978-5-93680-337-6.

- А., ТАРАСОВ (1925). "Нельзя забывать, что в Карачае издревле вырабатывается замечательная «лактобацил-линовая» простокваша «айран», нельзя забывать, что родиной кефира, кефирного молока считается Карачай. Только здесь можно купить в засушенном виде похожие на крупную дробь кефирные грибки («гыпы», по-карачаевски). Германские ученые также считают Карачай родиной этого грибка…". Северо-Кавказский край. (in Russian). 9: 84.

- Altay F, Karbancıoglu-Güler F, Daskaya-Dikmen C, Heperkan D (October 2013). "A review on traditional Turkish fermented non-alcoholic beverages: microbiota, fermentation process and quality characteristics". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 167 (1): 44–56. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.06.016. PMID 23859403.

- "Origin of KEFIR". Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online.

- Prado MR, Blandón LM, Vandenberghe LP, Rodrigues C, Castro GR, Thomaz-Soccol V, Soccol CR (30 October 2015). "Milk kefir: composition, microbial cultures, biological activities, and related products". Frontiers in Microbiology. 6: 1177. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.01177. PMC 4626640. PMID 26579086.

- "kefir". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language.

- "kef (Kurdish)". Wiktionary.

- Willey JM, Sherwood L, Woolverton CJ, Prescott LM, Harley JP (2008). Prescott, Harley, and Klein's Microbiology (7th ed.). London: McGraw–Hill. p. 1040. ISBN 978-0-07-110231-5.

- "Milk. How much there is in this word..."

- Karaketov; Sabanchiev (2014). Karachays. Balkars. Moscow: .Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology. N.N. Miklouho-Maclay RAS. Science. ISBN 978-5-02-038043-1.

- Sando L (September 2015). "Kefir Consumption—a Growing Culture". International Milk Genomics Consortium. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2017.

- Arslan S (26 November 2014). "A review: chemical, microbiological and nutritional characteristics of kefir". CyTA – Journal of Food. 13 (3): 340–345. doi:10.1080/19476337.2014.981588.

- Rafinera. "Kefirin Faydaları". www.rafinera.com (in Turkish). Retrieved 2020-12-22. Transcribed in source as 'kundeps'.

- Народы Кавказа: Материальная культура. Пища и жилище. М.: Институт этнологии и антропологии РАН. 1995. p. 100.

- Диланян, З. Х. (1957). Milk and dairy products technology. Гос. изд-во сельхоз. лит-ры. p. 171.

- Karaketov; Sabanchiev (2014). Karachays. Balkars. Moscow: .Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology. N.N. Miklouho-Maclay RAS. Science. ISBN 978-5-02-038043-1.

- "Bek-Mirza Baychorov- biography". Archived from the original on 1/22/2021/. Check date values in:

|archive-date=(help) - "KEFIR – Ecosaving.net – EU GREEN REVOLUTION". 2020-04-05. Archived from the original on 2020-04-05. Retrieved 2020-12-22.

- "Bek Mirza Baychorov-Karachay Uzden, exactly.. | | History of the Caucasus| | ВКонтакте". m.vk.com. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- "Bek Mirza Baychorov-Karachay Uzden, exactly.. | | History of the Caucasus | | ВКонтакте". m.vk.com. Retrieved 2020-12-06.

- Kowsikowski F, Mistry V (1997). Cheese and Fermented Milk Foods. I (3rd ed.). Westport, Conn.: FV Kowsikowski. ISBN 978-0-9656456-0-7.

- Wang SY, Chen KN, Lo YM, Chiang ML, Chen HC, Liu JR, Chen MJ (December 2012). "Investigation of microorganisms involved in biosynthesis of the kefir grain". Food Microbiology. 32 (2): 274–85. doi:10.1016/j.fm.2012.07.001. PMID 22986190.

- Wyder MT, Meile L, Teuber M (September 1999). "Description of Saccharomyces turicensis sp. nov., a new species from kefyr". Systematic and Applied Microbiology. 22 (3): 420–5. doi:10.1016/S0723-2020(99)80051-4. PMID 10553294.

- Vancanneyt M, Mengaud J, Cleenwerck I, Vanhonacker K, Hoste B, Dawyndt P, et al. (March 2004). "Reclassification of Lactobacillus kefirgranum Takizawa et al. 1994 as Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens subsp. kefirgranum subsp. nov. and emended description of L. kefiranofaciens Fujisawa et al. 1988". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 54 (Pt 2): 551–556. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02912-0. PMID 15023974.

- Federici F, Manna L, Rizzi E, Galantini E, Marini U (August 2018). Dennehy JJ (ed.). "Draft Genome Sequence of Lactobacillus kefiri SGL 13, a Potential Probiotic Strain Isolated from Kefir Grains". Microbiology Resource Announcements. 7 (4): e00937–18, e00937–18. doi:10.1128/MRA.00937-18. PMC 6256422. PMID 30533877.

- de Oliveira Leite AM, Miguel MA, Peixoto RS, Rosado AS, Silva JT, Paschoalin VM (October 2013). "Microbiological, technological and therapeutic properties of kefir: a natural probiotic beverage". Brazilian Journal of Microbiology. 44 (2): 341–9. doi:10.1590/S1517-83822013000200001. PMC 3833126. PMID 24294220.

- Ninane V, Berben G, Romne J, Oger R (2005). "Variability of the microbial abundance of kefir grain starter cultivated in partially controlled conditions" (PDF). Biotechnologie, Agronomie, Société et Environnement. 5 (3): 191–194. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-02-16.

- Kourkoutas Y, Kandylis P, Panas P, Dooley JS, Nigam P, Koutinas AA (September 2006). "Evaluation of freeze-dried kefir coculture as starter in feta-type cheese production". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72 (9): 6124–35. doi:10.1128/AEM.03078-05. PMC 1563647. PMID 16957238.

- Mei J, Guo Q, Wu Y, Li Y (2014-10-31). Al-Ahmad A (ed.). "Microbial diversity of a Camembert-type cheese using freeze-dried Tibetan kefir coculture as starter culture by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods". PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e111648. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1648M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111648. PMC 4216126. PMID 25360757.

- Nikolaou A, Sgouros G, Mitropoulou G, Santarmaki V, Kourkoutas Y (January 2020). "Freeze-Dried Immobilized Kefir Culture in Low Alcohol Winemaking". Foods. 9 (2): 115. doi:10.3390/foods9020115. PMC 7073665. PMID 31973003.

- Van Wyk J (2019). "12 - Kefir: The Champagne of Fermented Beverages". Fermented Beverages. 5: 473–527. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-815271-3.00012-9. ISBN 978-0-12-815271-3.

- Farnworth ER (2005). "Kefir – a complex probiotic" (PDF). Food Science and Technology Bulletin: Functional Foods. 2 (1): 1–17. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.583.6014. doi:10.1616/1476-2137.13938. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-29.

- Laureys D, De Vuyst L (April 2014). Griffiths MW (ed.). "Microbial species diversity, community dynamics, and metabolite kinetics of water kefir fermentation". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 80 (8): 2564–72. doi:10.1128/aem.03978-13. PMC 3993195. PMID 24532061.

- Rabl W, Liniger B, Sutter K, Sigrist T (March 1994). "[Ethanol content of Kefir water]". Blutalkohol (in German). 31 (2): 76–9. PMID 8204224.

- Gorgus E, Hittinger M, Schrenk D (September 2016). "Estimates of Ethanol Exposure in Children from Food not Labeled as Alcohol-Containing". Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 40 (7): 537–42. doi:10.1093/jat/bkw046. PMC 5421578. PMID 27405361.

- Farnworth E (2008). Handbook of fermented functional foods (second ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4200-5328-9. OCLC 646745830.

- Guzel-Seydim ZB, Kok-Tas T, Greene AK, Seydim AC (March 2011). "Review: functional properties of kefir". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 51 (3): 261–8. doi:10.1080/10408390903579029. PMID 21390946. S2CID 19963871.

- "Nutrition facts for fluid sheep milk, one US cup, 245 ml". Conde Nast, Nutritiondata.com, USDA Nutrient Database, Standard Reference, version 21. 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- Odet G (1995). "Fermented Milks". IDF Bull. 300: 98–100.

- Ahmed Z, Wang Y, Ahmad A, Khan ST, Nisa M, Ahmad H, Afreen A (2013). "Kefir and health: a contemporary perspective". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 53 (5): 422–34. doi:10.1080/10408398.2010.540360. PMID 23391011. S2CID 5166812.

- Farnworth ER (4 April 2005). "Kefir-a complex probiotic" (PDF). Food Science and Technology Bulletin: Functional Foods. 2 (1): 1–17. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.583.6014. doi:10.1616/1476-2137.13938. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- Motaghi M, Mazaheri M, Moazami N, Farkhondeh A, Fooladi MH, Goltapeh EM (1997). "Kefir production in Iran" (PDF). World Journal of Microbiology & Biotechnology. 13 (5): 579–581. doi:10.1023/A:1018577728412. S2CID 85138812. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 1, 2008.

- "Fabrication of kefir". Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 12 November 2013.

- Chen TH, Wang SY, Chen KN, Liu JR, Chen MJ (July 2009). "Microbiological and chemical properties of kefir manufactured by entrapped microorganisms isolated from kefir grains" (PDF). Journal of Dairy Science. 92 (7): 3002–13. doi:10.3168/jds.2008-1669. PMID 19528577.

- Maeda H, Zhu X, Suzuki S, Suzuki K, Kitamura S (August 2004). "Structural characterization and biological activities of an exopolysaccharide kefiran produced by Lactobacillus kefiranofaciens WT-2B(T)". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 52 (17): 5533–8. doi:10.1021/jf049617g. PMID 15315396.

- Abraham AG, De Antoni GL (May 1999). "Characterization of kefir grains grown in cows' milk and in soya milk". The Journal of Dairy Research. 66 (2): 327–33. doi:10.1017/S0022029999003490. PMID 10376251.

External links

| Look up kefir in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Fermented Foods: Kefir, from the National Center for Home Food Preservation

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.