Plazomicin

Plazomicin, sold under the brand name Zemdri, is an aminoglycoside antibiotic used to treat complicated urinary tract infections.[1] As of 2019 it is recommended only for those in whom alternatives are not an option.[1] It is given by injection into a vein.[1]

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | pla" zoe mye' sin |

| Trade names | Zemdri |

| Other names | ACHN-490, 6'-(Hydroxylethyl)-1-(HABA)-sisomicin |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a618037 |

| License data |

|

| Routes of administration | Intravenous infusion |

| Drug class | Aminoglycoside |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| Chemical and physical data | |

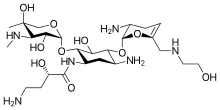

| Formula | C25H48N6O10 |

| Molar mass | 592.691 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

Common side effects include kidney problems, diarrhea, nausea, and blood pressure changes.[1] Other severe side effects include hearing loss, Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, anaphylaxis, and muscle weakness.[1] Use during pregnancy may harm the baby.[1] Plazomicin works by decreasing the ability of bacteria to make protein.[1]

Plazomicin was approved for medical use in the United States in 2018.[2][3] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[4]

Medical uses

Plazomicin is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for adults with complicated urinary tract infections, including pyelonephritis, caused by Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, or Enterobacter cloacae, in patients who have limited or no alternative treatment options. Zemdri is an intravenous infusion, administered once daily.[5][6][7][8] The FDA declined approval for treating bloodstream infections due to lack of demonstrated effectiveness.[2]

Plazomicin has been reported to demonstrate in vitro synergistic activity when combined with daptomycin or ceftobiprole versus methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant S. aureus and against Pseudomonas aeruginosa when combined with cefepime, doripenem, imipenem or piperacillin/tazobactam.[9] It also demonstrates potent in vitro activity versus carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii.[10] Plazomicin was found to be noninferior to meropenem.[11][12]

History

The drug was developed by the biotech company Achaogen. In 2012, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted fast track designation for the development and regulatory review of plazomicin.[13] The FDA approved plazomicin for adults with complicated UTIs and limited or no alternative treatment options in 2018.[5] Achaogen was unable to find a robust market for the drug, and declared bankruptcy a few months later.[14] A generic version is manufactured by Cipla USA.[15]

Synthesis

It is derived from sisomicin by appending a hydroxy-aminobutyric acid substituent at position 1 and a hydroxyethyl substituent at position 6'.[16][9]

Names

Plazomicin is the international nonproprietary name (INN).[17]

References

- "Plazomicin Sulfate Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 10 October 2019.

- "FDA Approved Drug Products: Zemdri". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- "Drug Approval Package: Zemdri (plazomicin)". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 5 July 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- "Zemdri (plazomicin)- plazomicin injection". DailyMed. 30 July 2020. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- "plazomicin (Rx)". Medscape. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- Brown T (3 May 2018). "FDA Panel Recommends Plazomicin for cUTI but Not BSI". Medscape. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- "BioCentury - FDA approves plazomicin for cUTI, but not blood infections". www.biocentury.com. Retrieved 28 June 2018.

- Zhanel GG, Lawson CD, Zelenitsky S, et al. (April 2012). "Comparison of the Next-Generation Aminoglycoside Plazomicin to Gentamicin, Tobramycin and Amikacin". Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 10 (4): 459–73. doi:10.1586/eri.12.25. PMID 22512755. S2CID 31496981.

- García-Salguero C, Rodríguez-Avial I, Picazo JJ, et al. (October 2015). "Can Plazomicin Alone or in Combination Be a Therapeutic Option against Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii?" (PDF). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 59 (10): 5959–66. doi:10.1128/AAC.00873-15. PMC 4576036. PMID 26169398. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- Clinical trial number NCT02486627 for "A Study of Plazomicin Compared With Meropenem for the Treatment of Complicated Urinary Tract Infection (cUTI) Including Acute Pyelonephritis (AP) (EPIC)" at ClinicalTrials.gov

- Wagenlehner FM, Cloutier DJ, Komirenko AS, et al. (21 February 2019). "Once-Daily Plazomicin for Complicated Urinary Tract Infections". New England Journal of Medicine. 380 (8): 729–740. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1801467. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 30786187. Lay summary – Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (21 February 2019).

- "Achaogen Announces Plazomicin Granted QIDP Designation by FDA" (Press release). Achaogen, Inc. 8 January 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2016 – via GlobeNewswire.

- Jacobs A (25 December 2019). "Crisis Looms in Antibiotics as Drug Makers Go Bankrupt". The New York Times.

- "Generic Zemdri Availability". Drugs.com. Retrieved 26 December 2019.

- Aggen JB, Armstrong ES, Goldblum AA, et al. (November 2010). "Synthesis and Spectrum of the Neoglycoside ACHN-490" (PDF). Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 54 (11): 4636–4642. doi:10.1128/AAC.00572-10. PMC 2976124. PMID 20805391.

- "International Nonproprietary Names for Pharmaceutical Substances (INN). Recommended INN: List 68". WHO Drug Information. World Health Organization. 26 (3): 314. September 2012. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

Further reading

- "FDA Briefing Information for the May 2, 2018 Meeting of the Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2 May 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- "Achaogen Briefing Information for the May 2, 2018 Meeting of the Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2 May 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- "Errata to the Achaogen Briefing Information for the May 2, 2018 Meeting of the Antimicrobial Drugs Advisory Committee" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2 May 2018. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

External links

- "Plazomicin". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Plazomicin sulfate". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.