Political history of Zimbabwe

The modern political history of Zimbabwe starts with the arrival of white people to what was dubbed Southern Rhodesia in the 1890s. The country was initially run by an administrator appointed by the British South Africa Company. The prime ministerial role was first created in October 1923, when the country achieved responsible government, with Sir Charles Coghlan as its first Premier. The third Premier, George Mitchell, renamed the post Prime Minister in 1933.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Zimbabwe |

The Rhodesian Prime Minister acted as Head of His or Her Majesty's Rhodesian Government, under the largely symbolic supervision of a British colonial Governor, until Rhodesia issued its unrecognised Unilateral Declaration of Independence on 11 November 1965. British-appointed figures such as the Governor were thereafter ignored by Salisbury. The unrecognised state's system of government, however, remained otherwise unchanged, right down to its declared loyalty to Elizabeth II, which Britain did not acknowledge. This situation remained until March 1970, when Rhodesia adopted a republican system of government. In republican Rhodesia, the Prime Minister instead nominally reported to the President.

The Prime Minister was responsible for nominating the other members of the government, chairing meetings of the Rhodesian Cabinet, and deciding when to call a new general election for the House of Assembly. He retained this role following the reconstitution of Rhodesia under black majority rule, first into Zimbabwe Rhodesia in 1979, then into Zimbabwe the following year. The Zimbabwean government was headed by a Prime Minister from 1980 to 1987, when that post was superseded by an executive presidency. The former Prime Minister, Robert Mugabe, became President; he was succeeded by Emmerson Mnangagwa during the 2017 coup d'état.

1890–1923: British South Africa Company rule

Context

Having secured the Rudd Concession on mining rights from King Lobengula of Matabeleland on 30 October 1888,[1] Cecil Rhodes and his British South Africa Company were granted a Royal Charter by Queen Victoria in October 1889.[2] Under this charter, the Company was empowered to trade with indigenous rulers, form banks, own and manage land, and raise and run a police force.[n 1] In return for these rights, the British South Africa Company would administer and develop any territory it acquired, while respecting laws enacted by extant African rulers, and upholding free trade within its borders. Though the Company made good on most of these pledges, the assent of Lobengula and other native leaders, particularly regarding mining rights, was often evaded, misrepresented or simply ignored.[2] Lobengula reacted by making war on the new arrivals, their Tswana allies and the local Mashona people in 1893. The resulting conflict ended with Lobengula's torching of his own capital at Bulawayo,[4] his death from smallpox in early 1894,[5] and the subsequent submission of his izinDuna (advisors) to the Company.[4] Violent rebellion to the north-east, in neighbouring Mashonaland, was forcibly put down by the Company during 1897.[6]

Following these victories, the British South Africa Company controlled a country equivalent to modern Zambia and Zimbabwe. This domain was initially referred to as "Zambesia" (or Zambezia) after the Zambezi, which bisected it; however, the first immigrants almost immediately began instead calling their new home "Rhodesia" in honour of their Company benefactor, and this name was officially adopted in 1895.[n 2] Matabeleland and Mashonaland, both of which lay south of the Zambezi, were first formally referred to by Britain as "Southern Rhodesia" in 1898,[8] and were united under that name in 1901. The areas to the river's north, Barotziland-North-Western Rhodesia and North-Eastern Rhodesia, were governed separately, and amalgamated in 1911 to form Northern Rhodesia.[9]

Company administrators

Hover your mouse over each man for his name; click for more details.

The head of the southern territories' government during this time was in effect the Company's regional administrator. The first of these was appointed in 1890, soon after the Pioneer Column's establishment of Fort Salisbury, the capital, on 12 September that year.[10] From 1899, the administrator governed as part of a ten-man Legislative Council, originally made up of himself, five other members nominated by the Company, and four elected by registered voters.[11] The number of elected members rose gradually under Company rule until they numbered 13 in 1920, sitting alongside the administrator and six other Company officials in the 20-member Legislative Council.[12] The Company's Royal Charter, which originally ran out in October 1914,[13] was renewed for a further ten years in 1915.[2]

The post of national administrator was held by three people, with three others holding the post while it only covered Mashonaland; between 1898 and 1901, a separate office existed in Matabeleland.[14]

| Name | Term of office | Post(s) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sir Archibald Ross Colquhoun (1848–1914) |

1 October 1890 |

10 September 1894 |

Administrator of Mashonaland |

| Dr Leander Starr Jameson (1853–1917) |

10 September 1894 |

2 April 1896[n 3] |

Administrator of Mashonaland |

| Albert Grey 4th Earl Grey (1851–1917) |

2 April 1896 |

5 December 1898 |

Administrator of Mashonaland |

| Sir William Henry Milton (1854–1930) |

5 December 1898 |

20 December 1901 |

Senior Administrator of Southern Rhodesia Administrator of Mashonaland |

| Arthur Lawley 6th Baron Wenlock (1860–1932) |

Administrator of Matabeleland | ||

| Sir William Henry Milton (1854–1930) |

20 December 1901 |

1 November 1914 |

Administrator of Southern Rhodesia |

| Sir Francis Drummond Chaplin (1866–1933) |

1 November 1914 |

1 September 1923 |

Administrator of Southern Rhodesia |

Frontier politics: towards responsible government

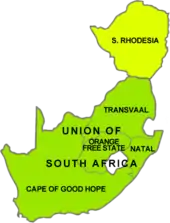

Southern Rhodesians of all races fought for Britain in the First World War, during which the Responsible Government Association (RGA) was formed in 1917. By 1919, Sir Charles Coghlan, a South African-born Bulawayo lawyer, had become the RGA's leader.[16] The RGA sought self-government for Southern Rhodesia within the British Empire—the same "responsible government" previously granted to Britain's colonies in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa as a precursor to full dominion status—and opposed Southern Rhodesia's proposed integration into the recently formed Union of South Africa. The accession of territories governed by the British South Africa Company was explicitly provisioned for by Section 150 of the South Africa Act 1909, the British Act of Parliament which created the union in 1910 by consolidating the Empire's Cape, Natal, Orange River and Transvaal Colonies into a unitary dominion. The Company originally stood against Southern Rhodesia's addition, fearing the territory's potential domination by Afrikaners,[17] but changed its tune dramatically when, in 1918, the Privy Council in London ruled that unalienated land in the Rhodesias was owned not by the Company but by the Crown.[17]

The loss of the ability to raise funds through the sale of land hampered the Company's ability to pay dividends to its shareholders, and caused its development of Southern Rhodesia to slow. Believing that membership in the union could help solve both problems,[17] the Company now backed Southern Rhodesia's incorporation as South Africa's fifth province.[18] However, this prospect proved largely unpopular among Southern Rhodesian settlers, most of whom wanted self-government, and came to vote for the RGA in large numbers.[17] In the 1920 Legislative Council election, the RGA won ten of the 13 seats contested.[19] A referendum on the colony's future was held on 27 October 1922—at the suggestion of Winston Churchill, then Britain's Colonial Secretary, continuing the initiative of his preprocessor Viscount Milner—and responsible government won the day by 59%.[20] Southern Rhodesia was duly annexed by the Empire on 12 September 1923, and granted full self-government on 1 October the same year.[21] The new Southern Rhodesian government immediately purchased the land from the British Treasury for £2 million,[22] and ten years later paid the same sum to the British South Africa Company for the country's mineral rights.[23]

1923–1965: colonial Prime Ministers

Responsible government; early years (1923–53)

The RGA reorganised itself to become the governing Rhodesia Party, with Coghlan as Southern Rhodesia's first Premier.[24][25] The title was changed to Prime Minister in 1933 by George Mitchell, the third man to hold the office.[25] In 1932, the Southern Rhodesian leader was first invited to an Imperial Conference. Although Southern Rhodesia was not a dominion, it was seen elsewhere in the Empire as a sui generis case among Britain's colonies, and worthy of inclusion, particularly as it was the only one which governed itself.[26] Southern Rhodesian Prime Ministers thereafter became a regular fixture at such meetings and, from 1944, at Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conferences.[27]

The Rhodesia Party remained in power until September 1933, when, despite narrowly topping the popular vote, it lost the month's election, winning only nine of the 30 seats compared to the Reform Party's 16.[28] Although the Reform Party was left-wing in name, many of its leading members, including the new Prime Minister Dr Godfrey Huggins, were politically conservative; the more rightist members of the party merged with the Rhodesia Party in 1934 to form the United Party, and, with Huggins at the helm, roundly defeated the rump left wing of the Reform Party to begin 28 years of uninterrupted stewardship.[29]

Though uninvolved in foreign affairs, and therefore obliged to follow Britain's lead, the colony enthusiastically supported the mother country during the Second World War, symbolically affirming the British declaration of war before any other part of the Empire.[n 4] During the ensuing conflict over 26,100 Southern Rhodesians of all races served in the armed forces, pro rata to white population a higher contribution of manpower than any other British colony or dominion, and more than the UK itself.[31] George VI knighted Huggins in 1941,[32] and, with the war still ongoing, Britain made overtures towards dominion status. Huggins dismissed this, saying it was imperative to win the war first.[33] The idea of dominionship was raised again in 1952,[33] but Salisbury once more did not pursue it, instead following the results of a referendum held early the next April to enter an initially semi-independent Federation with the directly administered British colonies of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland.[33]

Reform Party |

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency/Title |

Term of office — Electoral mandates |

Other ministerial offices held while Premier / Prime Minister |

Political party of PM |

Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sir Charles Coghlan (1863–1927) MP for Bulawayo North |

1 October 1923 |

28 August 1927 (died in office) |

Minister for Native Affairs | Rhodesia Party | [35] | |

| 1924 | |||||||

| Howard Moffat (1869–1951) MP for Gwanda |

2 September 1927 |

5 July 1933 |

Minister for Native Affairs | Rhodesia Party | [35] | ||

| 1928 | |||||||

| George Mitchell (1867–1937) MP for Gwanda |

5 July 1933 |

12 September 1933 |

– | Rhodesia Party | [35] | ||

| – | |||||||

| Sir Godfrey Huggins (1883–1971) MP for Salisbury North |

12 September 1933 |

7 September 1953 |

|

Reform Party (1933–34) | [35] | ||

| 1933, 1934, 1939, 1946, 1948 | United Party (1934–53) | ||||||

As a territory in the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (1953–63)

A month after Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland formed the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland in August 1953, Huggins became the amalgamated body's first Prime Minister.[36] Salisbury was designated the Federal capital,[37] and the United Party renamed itself the United Rhodesia Party.[24] Garfield Todd took over as Southern Rhodesia's Prime Minister.[24] Huggins headed the Federal government for three years, then retired in November 1956 after a combined 23 years as a national leader.[36] The United Rhodesia Party merged with the Federal Party to become the United Federal Party (UFP) in November 1957,[24] and the liberal Todd was voted out of office by the more right-wing members of his party four months later, in February 1958.[38] He was replaced by Sir Edgar Whitehead.[25] Todd led his own version of the United Rhodesia Party against the UFP and the Dominion Party in June the same year, but failed to win a single seat—the UFP won 17 of the 30 seats, with the Dominion Party taking the remainder.[34]

Whitehead served as Prime Minister for the next four years,[25] under Federal leader Roy Welensky, as black nationalist ambitions and changing international attitudes propelled the Federation towards collapse.[39] In Southern Rhodesia, constitutional changes adopted in 1961 as the result of a referendum split the heretofore non-racial (though qualified) electoral roll into graduated "A" and "B" rolls; the latter had lower qualifications, and was intended to cater for prospective black voters who had previously not qualified.[40]

This plan was given assent by the Southern Rhodesian and British governments, and initially enjoyed support from black nationalists in the country, though the latter soon reversed their stance, saying the changes did not go far enough. Some government members opposed this partitioning of the electorate, which essentially divided it along ethnic lines; the UFP's chief whip in the Federal assembly, Ian Smith, resigned in protest, saying the new system was "racialist".[40] Former Dominion Party leader Winston Field formed the pro-independence Rhodesian Front (RF) in 1962 to contest that November's Southern Rhodesian election, with Smith running as his deputy, and in a shock result won 35 of the 50 territorial "A"-roll seats.[24] Field and Smith became Prime Minister and Deputy Prime Minister respectively,[41] and remained in office after the Federation's dissolution on the last day of 1963.[42]

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency/Title |

Term of office — Electoral mandates |

Other ministerial offices held while Prime Minister |

Political party of PM |

Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Garfield Todd (1908–2002) MP for Shabani |

7 September 1953 |

17 February 1958 |

Minister for Native Affairs | United Rhodesia Party | [35] | |

| 1954 | |||||||

|

Sir Edgar Whitehead (1905–1971) MP for Salisbury North |

17 February 1958 |

17 December 1962 |

Minister for Native Affairs | United Federal Party | [35] | |

| 1958 | |||||||

|

Winston Field (1904–1969) MP for Marandellas |

17 December 1962 |

31 December 1963 |

– | Rhodesian Front | [35] | |

| 1962 | |||||||

From Federation to UDI (1964–65)

After the Federation broke up on 31 December 1963,[42] Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland became independent during 1964, respectively renamed Zambia and Malawi, and under black majority governments.[43] Southern Rhodesia was denied the same under the ideal of "no independence before majority rule" that was newly ascendant in Britain and elsewhere. The RF was enraged by what it saw as British duplicity; according to Field and Smith, Britain's Deputy Prime Minister and First Secretary of State R. A. Butler had verbally promised "independence no later than, if not before, the other two territories" at a meeting in 1963, in return for Salisbury's help in winding up the Federation. Butler denied having said this.[44]

Under severe pressure from his ministers to resolve this issue, Field travelled to England in March 1964 to pursue sovereign statehood, but returned empty-handed a month later. He resigned his position on 13 April; this came as no surprise to many government insiders, but appeared sudden to most sections of the general public. Smith promptly accepted the cabinet's invitation to take over, though he expressed surprise at the nomination.[45] A farmer and erstwhile British Royal Air Force pilot from the rural town of Selukwe, Smith was Southern Rhodesia's first native-born head of government.[46] He immediately promised to take a harder line on independence than his predecessor.[45]

Only two months into his premiership, Smith was deeply offended when Whitehall informed him that, for the first time since 1930, Southern Rhodesia would not be represented at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference.[47] Huggins described this in 1969 as tantamount to "kicking [Southern Rhodesia] out of the Commonwealth".[48] When Northern Rhodesia became Zambia on 24 October 1964, Southern Rhodesia dropped "Southern" from its name, and initiated legislation to this effect. Britain refused assent two months later, saying that although the colony was self-governing, it did not have the power to rename itself. Salisbury continued using the shortened name anyway.[49]

The Rhodesian government, which remained predominantly white, contended that it had almost complete support from all races in its drive for full statehood; in October 1964, a national indaba (tribal conference) comprising 622 black representatives unanimously backed independence under the 1961 constitution, and a month later a general independence referendum yielded an 89% "yes" vote for the same.[50] Harold Wilson's British Labour Cabinet did not give credence to either of these tests of opinion, and continued to insist on an immediate shift to majority rule before the granting of sovereign independence.[51] Campaigning on an election promise of independence, the RF called a new general election for May 1965, and won all 50 "A"-roll seats.[24]

Negotiations between Smith and Wilson took place throughout the rest of the year, but repeatedly broke down; between July and September, a parallel development concerned Rhodesia's opening of a representative mission in Lisbon, which Britain opposed, but proved unable to stop.[52] Soon after Smith visited London in October 1965, Wilson resolved to curb his rival's ambitions. During his own visit to Salisbury later that month, he proposed to safeguard future black representation in the Rhodesian parliament by withdrawing control over the Rhodesian parliamentary structure to London. Salisbury had held these powers since 1923.[53] This proved the last straw for Smith's Rhodesian government, which issued the Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 11 November.[54]

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency/Title |

Term of office — Electoral mandates |

Other ministerial offices held while Prime Minister |

Political party of PM |

Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Winston Field (1904–1969) MP for Marandellas |

1 January 1964 |

13 April 1964 |

– | Rhodesian Front | [35] | |

| – | |||||||

|

Ian Smith (1919–2007) MP for Umzingwane |

13 April 1964 |

11 November 1965 |

– | Rhodesian Front | [35] | |

| 1965 | |||||||

1965–80: UDI era

Unrecognised state (1965–79)

.svg.png.webp)

The Rhodesians modelled their independence document on that of the American Thirteen Colonies in 1776, which remains the only other such proclamation in the history of the British Empire.[56] According to UDI—which went unrecognised by Britain, the Commonwealth and the United Nations, all of which declared it illegal and imposed economic sanctions—the Rhodesian government still professed loyalty to Elizabeth II, whom it called the "Queen of Rhodesia".[56] The British-appointed Governor, Sir Humphrey Gibbs, remained at his post in Government House, Salisbury, but was now ignored by the local government, which appointed its own "Officer Administrating the Government" to fill his ceremonial role.[57] Smith represented Rhodesia in two abortive rounds of talks with Wilson, first aboard HMS Tiger in 1966,[58] then on HMS Fearless two years later.[59] Under Rhodesia's 1965 constitution, the Prime Minister remained at the head of Her Majesty's Rhodesian Government until 2 March 1970, when a republican constitution was adopted in line with the results of a referendum held the previous June. In the Republic of Rhodesia, the Prime Minister formally reported to the President.[60]

Smith and the RF decisively won three more general elections during the 1970s.[24] The Anglo-Rhodesian Agreement of 1971–72, which would have legitimised the country's independence in Britain's eyes, fell apart after a British test of Rhodesian national opinion reported most blacks to be against it.[61] The Rhodesian Bush War, fought against the government by the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army (ZANLA) and the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army (ZIPRA), the respective guerrilla armies of the Maoist Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and its Warsaw Pact-aligned Marxist rival, the Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU), intensified soon after, starting with ZANLA's attack on Altena and Whistlefield Farms in the country's north-east in December 1972.[62] After a strong security force counter-campaign, the South African détente initiative of December 1974 introduced a ceasefire, which the security forces respected, and the guerrillas ignored.[63] This shifted the course of the war significantly in the nationalists' favour.[63]

Mozambican independence under a communist government in 1975 further assisted the cadres,[64] and exacerbated the Rhodesian government's economic dependency on South Africa.[63] Unproductive talks between Smith and the guerrilla leaders took place at Victoria Falls in 1975,[65] then in Geneva the following year.[66] In March 1978, the Internal Settlement was agreed between the government and moderate nationalist parties, the most prominent of which was Bishop Abel Muzorewa's United African National Council (UANC).[67] The militant nationalist campaigns continued, however, and indeed extended to attacks on civilian aircraft: ZAPU shot down Air Rhodesia Flight 825 in September 1978, then Air Rhodesia Flight 827 in February 1979.[68] ZANU and ZAPU boycotted the elections held per the Internal Settlement in April 1979,[69] which UN Security Council Resolution 448 called "sham elections ... [held] in utter defiance of the United Nations".[70] In these elections, the UANC won a majority in the new House of Assembly, with 51 of the 72 common roll seats (for which universal suffrage applied) and 67% of the popular vote.[67] The RF took all 20 of the seats elected by white voters and also provided eight non-constituency members.[71] All of this settled, Rhodesia became black majority-ruled Zimbabwe Rhodesia on 1 June 1979, with Muzorewa replacing Smith as Prime Minister.[67]

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency/Title |

Term of office — Electoral mandates |

Other ministerial offices held while Prime Minister |

Political party of PM |

Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ian Smith (1919–2007) MP for Umzingwane |

11 November 1965 |

1 June 1979 |

– | Rhodesian Front | [35] | |

| 1970, 1974, 1977 | |||||||

Internal Settlement; interim British control (1979–80)

With Muzorewa and the UANC in government, Zimbabwe Rhodesia failed to gain international acceptance. ZANU leader Robert Mugabe publicly damned Muzorewa's new order, dismissing the bishop as a "neocolonial puppet";[69] he pledged to continue ZANLA's campaign "to the last man".[69] Muzorewa took office at the head of a UANC–RF coalition cabinet made up of 12 blacks and five whites. "Instead of the enemy wearing a white skin, he will soon wear a black skin," said Mugabe, just before the bishop took over.[69][71] The Bush War went on until December 1979, when Salisbury, Whitehall and the revolutionary nationalists signed the Lancaster House Agreement in London.[72] Zimbabwe Rhodesia came under the temporary control of Britain, and a Commonwealth monitoring force was convened to supervise fresh elections, in which ZANU and ZAPU would take part for the first time. ZANU won, and, with Mugabe as Prime Minister, formed the first government of Zimbabwe following its recognised independence on 18 April 1980.[73]

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency/Title |

Term of office — Electoral mandates |

Other ministerial offices held while Prime Minister |

Political party of PM |

Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_op_Schiphol%252C_Bestanddeelnr_929-9740.jpg.webp) |

Bishop Abel Muzorewa (1925–2010) MP for Mashonaland East |

1 June 1979 |

12 December 1979 |

Minister of Combined Operations Minister of Defence |

United African National Council | [35] | |

| 1979 | |||||||

Since 1980: Zimbabwe

Prime Minister and ceremonial President (1980–87)

Seven years into Mugabe's premiership, Zimbabwe scrapped the white seats amid sweeping constitutional reforms in September 1987. The office of Prime Minister was abolished in October; Mugabe became the country's first executive President two months later.[74] Mugabe and the ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo signed a unity accord at the same time merging ZAPU into ZANU–PF with the stated goal of a Marxist–Leninist one-party state.[75]

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency/Title |

Term of office — Electoral mandates |

Other ministerial offices held while Prime Minister |

Political party of PM |

Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Robert Mugabe (born 1924) MP for Mashonaland East (1980–85) MP for Highfield (1985–87)(Death 2019) |

18 April 1980 |

22 December 1987 |

Secretary-General of the Non-Aligned Movement (1986–89) | Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front | [35] | |

| 1980, 1985 | |||||||

Executive President (1987–present)

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) Constituency/Title |

Term of office — Electoral mandates |

Other offices held while President |

Political party of PM |

Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Robert Mugabe (born 1924) |

22 December 1987 |

21 November 2017 |

Secretary-General of the Non-Aligned Movement (1986–89) | Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front | [35] | |

| 1990, 1996, 2002, 2008, 2013 | |||||||

.jpg.webp) |

Emmerson Mnangagwa (born 1942) |

21 November 2017 |

present | Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front | |||

| 2018 | |||||||

Notes and references

Notes

- The police force raised by the Company, the British South Africa Company's Police, was renamed the Mashonaland Mounted Police in 1892. The Matabeleland Mounted Police was founded in 1895, and it and its Mashonaland counterpart collectively became referred to as the Rhodesia Mounted Police. This became the independently-run British South Africa Police (BSAP) in 1896. The BSAP retained its name and remained Rhodesia's law enforcement arm until 1980.[3]

- The first recorded use in this context is in the titles of the Rhodesia Chronicle and Rhodesia Herald newspapers, respectively first published at Fort Tuli and Fort Salisbury in May and October 1892. The Company officially applied the name Rhodesia in 1895.[7]

- Jameson offered his resignation immediately following his eponymous raid into the South African Republic in December 1895, but it was not accepted until April 1896.[15]

- Southern Rhodesia's government made this symbolic announcement in an attempt to demonstrate concurrent fealty to, and independence from, Britain. It was irrelevant in any legal or diplomatic sense as the self-governing colony's foreign affairs were still handled by Britain; so long as Britain was at war, Southern Rhodesia was as well. The Australian and New Zealand dominions were respectively in a similar situation, having not yet ratified the Statute of Westminster 1931, which, on adoption, transferred diplomatic responsibility from Britain to the relevant local government.[30]

- The United Party, formed in 1934, renamed itself the United Rhodesia Party in 1953, when the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland was created. In 1957, it merged with the Federal Party to become the United Federal Party.[24] It should not be confused with the rump United Rhodesia Party led by former Prime Minister Garfield Todd, which fought the 1958 general election, then promptly dissolved.[34]

References

- Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 77

- Encyclopædia Britannica 2012

- Gibbs, Phillips & Russell 2009, p. 3

- Ranger 2010, pp. 14–17

- Hopkins 2002, p. 191

- Wessels 2010, pp. 16–17

- Brelsford 1954

- Blake 1977, p. 114

- Brelsford 1960, p. 619

- Palley 1966, p. 149

- Willson 1963, p. 101

- Willson 1963, pp. 111–114

- Wessels 2010, p. 18

- Willson, Passmore & Mitchell 1966

- Wills & Barrett 1905, p. 260

- Blake 1977, p. 179

- Wood 2005, p. 8

- Okoth 2006, p. 123

- Willson 1963, p. 111

- Willson 1963, p. 115

- Willson 1963, p. 46

- Berlyn 1978, p. 103

- Blake 1977, p. 213

- Gale 1973, pp. 88–89

- Hutson 1978, p. 189

- St Brides 1980

- Berlyn 1978, pp. 134–142

- Willson 1963, p. 129

- Blake 1977, pp. 220–221

- Wood 2005, p. 9

- Moorcraft 1990

- Blake 1977, p. 238

- Wood 2005, p. 279

- Leys 1959, pp. 306–311

- Gale 1973, pp. 88–89; Hutson 1978, p. 189; Leys 1959, p. 136

- Gale 1973, pp. 43, 88

- Smith 1997, p. 33

- Leys 1959, p. 144

- Blake 1977, p. 331; Welensky 1964, p. 64

- Blake 1977, p. 335

- Smith 1997, p. 47

- Wood 2005, p. 189

- Wood 2005, p. 38

- Wood 2005, pp. 138–140, 167; Berlyn 1978, p. 135; Smith 1997, pp. 51–52

- Berlyn 1978, pp. 131–132; Wessels 2010, pp. 102–104

- Berlyn 1978, p. 35

- Smith 1997, p. 70

- Berlyn 1978, pp. 140, 143

- Palley 1966, pp. 742–743

- The Sydney Morning Herald 1964; Harris 1969; Berlyn 1978, pp. 144–146; Wessels 2010, p. 105

- Wood 2005, pp. 418–420, 445; Wessels 2010, p. 105

- Fedorowich & Thomas 2001, pp. 185–186

- Wood 2005, pp. 412–414

- Wood 2005, pp. 468–475

- Barraclough & Crampton 1978, p. 157

- Wood 2008, pp. 1–8

- Wood 2005, p. 471

- Wessels 2010, pp. 133–136; Wood 2008, pp. 229, 242–246

- Wessels 2010, pp. 149–152; Wood 2008, pp. 542–555

- Harris 1969; The New York Times 1970

- Smith 1997, pp. 152–157

- Binda 2008, pp. 133–136; ZANU 1974; Windsor Star 1976

- Cilliers 1984, pp. 22–24; Lockley 1990

- Binda 2008, p. 166; Duignan & Gann 1994, pp. 19–21

- BBC 1975

- Sibanda 2005, pp. 211–213; Smith 1997, pp. 213–217; Wessels 2010, p. 216

- Williams & Hackland 1988, p. 289

- Petter-Bowyer 2005, pp. 330–331

- Winn 1979

- UN Security Council 1979

- Gowlland-Debbas 1990, p. 79

- Gowlland-Debbas 1990, p. 89

- BBC 1979

- Chikuhwa 2004, pp. 38–39.

- Meredith 2007, p. 73.

Online sources

- "British South Africa Company (BSAC, BSACO, or BSA Company)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

Newspaper and journal articles

- Brelsford, W. V., ed. (1954). "First Records—No. 6. The Name 'Rhodesia'". The Northern Rhodesia Journal. Lusaka: Northern Rhodesia Society. II (4): 101–102. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- Harris, P. B. (September 1969). "The Rhodesian Referendum: June 20th, 1969" (pdf). Parliamentary Affairs. Oxford University Press. 23: 72–80. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Lockley, Lt-Col R. E. H. (July 1990). "A brief operational history of the campaign in Rhodesia from 1964 to 1978". The Lion & Tusk. Southampton: Rhodesian Army Association. 2 (1). Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- Moorcraft, Paul (1990). "Rhodesia's War of Independence". History Today. London: History Today Ltd. 40 (9). ISSN 0018-2753.

- Lord St Brides (April 1980). "The Lessons of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia". International Security. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. 4 (4): 177–184. doi:10.2307/2626673. JSTOR 2626673.

- Winn, Michael (7 May 1979). "Despite Rhodesia's Elections, Robert Mugabe Vows to Wage Guerrilla War 'to the Last Man'". People. New York: Time Inc. 11 (18). Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- "1975: Rhodesia peace talks fail". London: BBC. 26 August 1975. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- "Rhodesia reverts to British rule". London: BBC. 11 December 1979. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- "Rhodesia's First Day as a Republic Passes Quietly". The New York Times. 3 March 1970. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- "Britain 'Gets Tough': Warns Rhodesia Of 'Rebellion' Consequences". The Sydney Morning Herald. Fairfax Media. 28 October 1964. p. 3. Retrieved 18 November 2011.

- "USSR viewed as blacks' friend". The Windsor Star. Windsor, Ontario: Postmedia News. 9 November 1976. p. 20. Retrieved 20 June 2012.

Other documents

- "Resolution 448 (1979) Adopted by the Security Council at its 2143rd meeting". New York: UN Security Council. 30 April 1979. UN Document S/RES/448 (1979). Retrieved 11 March 2012.

- "Chimurenga war communiqué No. 8. Period from 30 Jan to 20 March 1974". Lusaka: Zimbabwe African National Union. 27 March 1974.

Bibliography

- Barraclough, E. M. C.; Crampton, William G., eds. (1978). Flags of the World (Third Illustrated ed.). London: Frederick Warne & Co. ISBN 978-0-7232-2015-2.

- Berlyn, Phillippa (April 1978). The Quiet Man: A Biography of the Hon. Ian Douglas Smith. Salisbury: M. O. Collins. OCLC 4282978.

- Binda, Alexandre (May 2008). The Saints: The Rhodesian Light Infantry. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-1-920143-07-7.

- Blake, Robert (1977). A History of Rhodesia. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 0-394-48068-6.

- Brelsford, W. V., ed. (1960). Handbook to the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. London: Cassell.

- Chikuhwa, Jacob (March 2004). A Crisis of Governance: Zimbabwe (First ed.). New York: Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-286-6.

- Cilliers, Jakkie (December 1984). Counter-Insurgency in Rhodesia. London, Sydney & Dover, New Hampshire: Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0-7099-3412-7.

- Duignan, Peter; Gann, Lewis H. (1994). Communism in Sub-Saharan Africa: a Reappraisal. Stanford, California: Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-3712-6.

- Fedorowich, Kent; Thomas, Martin, eds. (2001). International Diplomacy and Colonial Retreat. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-5063-0.

- Gale, William Daniel (1973). The Years Between 1923–1973: Half a Century of Responsible Government in Rhodesia. Salisbury: H. C. P. Andersen. OCLC 224687202.

- Gibbs, Peter; Phillips, Hugh; Russell, Nick (May 2009). Blue and Old Gold: The History of the British South Africa Police, 1889–1980. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-1-920143-35-0.

- Gowlland-Debbas, Vera (1990). Collective Responses to Illegal Acts in International Law: United Nations action in the question of Southern Rhodesia (First ed.). Leiden and New York: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-0811-5.

- Hopkins, Donald R. (September 2002) [1983]. The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-35168-1.

- Hutson, H. P. W. (March 1978). Rhodesia, Ending an Era (Second ed.). London: Springwood Books.

- Keppel-Jones, Arthur (1983). Rhodes and Rhodesia: The White Conquest of Zimbabwe, 1884–1902. Montreal, Quebec and Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0534-6.

- Leys, Colin (1959). European Politics in Southern Rhodesia (First ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Meredith, Martin (September 2007) [2002]. Mugabe: Power, Plunder and the Struggle for Zimbabwe. New York: PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-558-0.

- Okoth, Assa (2006). A History of Africa, Volume Two: African nationalism and the de-colonisation process (First ed.). Nairobi, Kampala and Dar es Salaam: East African Educational Publishers. ISBN 9966-25-358-0.

- Palley, Claire (1966). The Constitutional History and Law of Southern Rhodesia 1888–1965, with Special Reference to Imperial control. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ASIN B0000CMYXJ.

- Petter-Bowyer, P. J. H. (November 2005) [2003]. Winds of Destruction: the Autobiography of a Rhodesian Combat Pilot. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-0-9584890-3-4.

- Ranger, Terence O. (September 2010). Bulawayo Burning: The Social History of a Southern African City, 1893–1960. Oxford: James Currey. ISBN 978-1-84701-020-9.

- Sibanda, Eliakim M. (January 2005). The Zimbabwe African People's Union 1961–87: A Political History of Insurgency in Southern Rhodesia. Trenton, New Jersey: Africa Research & Publications. ISBN 978-1-59221-276-7.

- Smith, Ian (June 1997). The Great Betrayal: The Memoirs of Ian Douglas Smith. London: John Blake Publishing. ISBN 1-85782-176-9.

- Welensky, Roy (1964). Welensky's 4000 Days. London: Collins. ASIN B0006DBAJ6.

- Wessels, Hannes (July 2010). P. K. van der Byl: African Statesman. Johannesburg: 30° South Publishers. ISBN 978-1-920143-49-7.

- Williams, Gwyneth; Hackland, Brian (July 1988). The Dictionary of Contemporary Politics of Southern Africa (First ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-00245-5.

- Wills, Walter H.; Barrett, R. J. (1905). The Anglo-African Who's Who and Biographical Sketch-Book. London: George Routledge & Sons.

- Willson, F. M. G., ed. (1963). Source Book of Parliamentary Elections and Referenda in Southern Rhodesia, 1898–1962. Salisbury: Department of Government, University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

- Willson, F. M. G.; Passmore, G. C.; Mitchell, Margaret T., eds. (1966). Holders of Administrative and Ministerial Office, 1894–1964, and Members of the Legislative Council, 1899–1923, and the Legislative Assembly, 1924–1964. Salisbury: Department of Government, University of Rhodesia.

- Wood, J. R. T. (June 2005). So Far And No Further! Rhodesia's Bid For Independence During the Retreat From Empire 1959–1965. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4120-4952-8.

- Wood, J. R. T. (April 2008). A Matter Of Weeks Rather Than Months: The Impasse Between Harold Wilson and Ian Smith: Sanctions, Aborted Settlements and War 1965–1969. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4251-4807-2.