Politics of Bihar

The Politics of Bihar, an eastern state of India, is dominated by regional political parties. As of 2021, the main political parties are Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), Janata Dal (United) (JDU), Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and Indian National Congress (INC). There are also some smaller regional parties, including Rashtriya Lok Samata Party, Hindustani Awam Morcha, Jan Adhikar Party and Rashtriya Jan Jan Party and Lok Janshakti Party, which play a vital role in Bihar politics. As of 2021, Bihar is currently ruled by a coalition of the JDU and the BJP.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Bihar |

Administration and governments

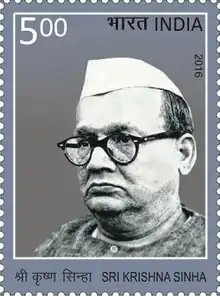

The constitutional head of the Government of Bihar is the Governor, who is appointed by the President of India. Executive power rests with the Chief Minister and the cabinet. The political party or the coalition of parties that has a majority in the Legislative Assembly forms the government. The first Chief Minister of Bihar was Krishna Sinha and the first Deputy Chief Minister was Anugrah Narayan Sinha.[1]

In 2014, the incumbent Chief Minister Nitish Kumar succeeded Jitan Ram Manjhi, who was sacked from his office.[2] In his previous term, Kumar resigned after the general election in 2014, after which Manjhi took over.

The head of the state bureaucracy is the Chief Secretary. Under him is a hierarchy of officials drawn from the Indian Administrative Service, Indian Police Service, and other wings of the state civil services. The judiciary is headed by the Chief Justice. Bihar has a High Court that has been functioning since 1916. All of the government headquarters are situated in the state capital Patna.

For administrative purposes, Bihar state has nine divisions—Patna, Tirhut, Saran, Darbhanga, Kosi, Purnia, Bhagalpur, Munger, and Magadh Division—which between them are subdivided into thirty-eight districts.[1]

History

Pre-Independence

Bihar was an important part of India's struggle for independence. Mahatma Gandhi became the movement's leader after the Champaran Satyagraha, launched in the state's Champaran district at the repeated request of a local leader Raj Kumar Shukla. He was also supported by Rajendra Prasad, Anugrah Narayan Sinha, and Brajkishore Prasad.

Post Independence : 1950–1975

The first Bihar governments in 1946 were led by Shri Krishna Sinha and Anugrah Narayan Sinha.[1] After the independence of India, power was shared by the Gandhian nationalists: Krishna Sinha became the first Chief Minister and Anugrah Narayan Sinha served as the first Deputy Chief Minister cum Finance Minister. The death of the central railway minister Lalit Narayan Mishra in a hand grenade attack in late 1960s brought an end to indigenous, work-oriented mass leaders. The Indian National Congress (INC) controlled the state for next two decades; at this time, prominent leader Satyendra Narayan Singh left the INC following ideological differences and joined the Janata Party.[1]

Bihar movement and aftermath: 1975–1990

After independence also, when India was falling into an autocratic rule during the Indira Gandhi regime, the main thrust to the movement to hold elections came from Bihar under the leadership of Jayaprakash Narayan .

In 1974, Narayan led the student's movement in Bihar, which gradually developed into the popular Bihar Movement, during which JP called for a peaceful "Total Revolution". He and V. M. Tarkunde founded the Citizens for Democracy in 1974 and the People's Union for Civil Liberties in 1976 to uphold and defend civil liberties. On 23 January 1977, Indira Gandhi called fresh elections for the following March and released all political prisoners. The Indian Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi officially ended on 23 March 1977.

In the election, the INC was defeated by the Janata Party, a coalition of several small parties created in 1977. The alliance was headed by Morarji Desai, who became the first non-INC Prime Minister of India.[3][4] The Janata Party won all the fifty-four Lok Sabha seats in Bihar, taking power in the state assembly. Karpoori Thakur became the Chief Minister after winning a contest from the then-Janata Party President Satyendra Narayan Sinha.

The Communist Party in Bihar was founded in 1939. From the 1960s to the 1980s, the Communist movement in the state was led by veteran communist leaders Jagannath Sarkar, Sunil Mukherjee, Rahul Sankrityayan, Pandit Karyanand Sharma, Indradeep Sinha, and Chandrashekhar Singh. Under the leadership of Sarkar, the Communist party fought the "total revolution" led by Jayprakash Narayan as the movement was anti-democratic and challenged the fabric of Indian democracy.[5]

The Bihar Movement campaign warned Indians that the elections might be their last chance to choose between "democracy and dictatorship". As a consequence of the movement, the identity of Bihar (from the word Vihar, meaning monasteries), representing a glorious past, was lost. Its voice often used to get lost in the din of regional clamour of other states, specially the linguistic states like Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh. Bihar also gained an anti-establishment image. The pro-establishment press often projected the state as undisciplined and anarchic.[6]

Because the regional identity was slowly being sidelined, it was replaced by caste-based politics; power was initially in the hands of the Brahmins, Bhumihars and Rajputs. In the 1980s there was a change in the political scenario of Bihar: riding upon a popular movement of "social justice" and no vote without representation, the middle OBC castes like Yadav, Kurmi, and Koeri replaced upper castes in politics.[7]

S.N. Singh's regime was known for deteriorating law and order, which included the 1989 Bhagalpur violence, one of the biggest riots in the state's history. A report tabled in the Bihar Legislative Assembly under the chairmanship of N.N. Singh blamed the Sinha-led INC government for the riots. The 1,000-page report outlined his and his administration's inactivity for almost two months, during which over 1,000 people—mostly poor Muslim weavers—were killed and 50,000 more were displaced.[8]

In 1989, an anti-Congress wave defeated the entrenched INC, and Janata Dal came to power on an anti-corruption wave. In between, the socialist movement lead by Mahamaya Prasad Sinha and Karpoori Thakur tried to break the status quoits. The movement failed, due to the impractical idealism of its leaders and to the machinations of the INC's central leaders, who felt threatened by the large, politically aware state.[6]

Under Lalu Yadav: 1990–2004

Janata Dal came to power in Bihar in 1990 after its 1989 national victory. Lalu Prasad Yadav became Chief Minister after narrowly winning the leadership contest of the legislative party against Ram Sundar Das, a former chief minister from the Janata Party and close to eminent Janata Party leaders Chandrashekhar and S.N. Sinha. Later, Yadav gained mass popularity with a series of populist measures. The principled socialists, including Nitish Kumar, gradually left him and by 1995, Yadav was both chief minister of the state and president of his party, Rashtriya Janata Dal. He was a popular, charismatic leader.[9]

Caste politics of Yadav

According to Seyed Hossein Zarhani, though Lalu Yadav became a figure of hatred among Forward Castes, he had much support from backward castes and Dalits. He was criticised for neglecting development but a study conducted during his premiership among Musahars revealed though the construction of houses for them was not concluded at the required pace, the chose Prasad because he returned them their ijjat (honour) and allowed them to vote for the first time.[10]

During Yadav's tenure, a number of populist policies that directly impacted his backward-caste supporters, including the establishment of "Charvaha schools" for poor children; abolition of cess on toddy, and the rules protecting backward castes were enforced. Yadav mobilised backwards castes through his identity politics. He viewed Forward Castes as elite in outlook and portrayed himself as the "Messiah of backwards" by living the same way as his mostly poor supporters. He continued to live in his single-room dwelling after being elected as Chief Minister, though he later moved to the official residence for administrative convenience.[10]

Another significant development during Yadav's premiership was the recruitment of large numbers backward castes and communities to government services. The government's white paper claimed to have a large number of vacancies in health and other sectors. The rules of recruitment were changed to benefit backward castes who supported Lalu. The frequent transfer of existing officers, who were at the higher echelon of bureaucracy, was an important feature of Yadav's and Rabri Devi's administration, and led to its collapse and that of the entire system. Yadav, however, continued to lead Bihar due to massive support from backward castes, to whom he projected "honour" to be more important than development. According to Zarhani, for the lower castes he was a charismatic leader who succeeded in becoming their voice.[10]

Yadav mobilised his Dalit supporters by popularising the lower-caste folk heroes, who were famed for vanquishing the upper caste adversaries, for example, a popular Dalit saint who ran away with an upper caste girl and suppressed all her kin. Praising him could enrage Bhumihar caste in some parts of Bihar but Yadav participated in a grand celebration every year near Patna. His energetic participation in this show made it a rallying point for Dalits, who saw it as their victory and the harassment of upper castes.[11]

Yadav could not restart development of the state. When corruption charges were laid against him, he resigned as chief minister and appointed his wife Rabri Devi, in his place, allowing himself to rule by proxy, and the administration quickly deteriorated.[12]

According to Kalyani Shankar, Yadav created a feeling among the oppressed castes they are the real rulers of state under him. The upper caste, 13.2% of the population, controlled most of the land while the backwards castes, 51% of the population, own very little land. With the advent of Yadav, the economic profile of the state changed as the backward castes diversified their occupations and also controlled more land. By stopping Lal Krishna Advani's controversial "Ram Rath Yatra", Yadav also installed a sense of confidence among Muslims, who developed a sense of insecurity after the 1989 Bhagalpur Riots. According to Shankar, during this period, upper castes were marginalised and backwards castes came to control the power firmly.[13]

Rabri Devi's administration

When Rabri Devi succeeded Lalu Yadav as Chief Minister, Yadav, who was jailed, was still able to influence the government. This period saw the rise of strongmen from both upper and backward castes. The Yadav-Rabri administration was not supported by Forward Castes due to their political and socio-economic marginalisation under Yadav's rule. A number of influential criminals, who were portrayed as leaders of their castes, entered politics as a reaction against Yadav's "backward caste politics".[14] People like Vijay Kumar Shukla (Munna Shukla), Anand Mohan Singh, Rama Singh and Prabhunath Singh supported the upper castes by launching retribution against lower and middle castes. In Vaishali district, for example, Munna Shukla and his associates consistently clashed with Yadav's minister Brij Bihari Prasad, a Bania, resulting in assassination of Chhotan Shukla, Munna's brother and associate, in the retribution of which Prasad was also killed. Anand Mohan also brought havoc to the supporters of a Reservation and Mandal Commission report by forming his "Samajwadi Krantikari Sena", which was a lynching party of upper castes until it was taken over by Yadav's close confidante Pappu Yadav.[15] Munna Shukla and Anand Mohan were were convicted of the murder of Gopalganj District Magistrate, G. Krishnaiah, a Dalit.[16]

Lalu Yadav's brothers-in-law Sadhu Yadav and Subhash Prasad Yadav, were also running parallel governments in their own areas of influence.[17] Devi was not able to cope with the situation, nor with the flourishing private armies of the landlords, which had existed since the 1960s. In retaliation, the landless labourers and the poor middle-caste peasantry began their own organisations, such as Lal Sena and the Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation.

A number of big massacres had also taken place in the decades before Yadav's and Rabri's administrations. In the Dalelchak-bhagora massacre, during Bindeshwari Dubey's government, 42 Rajputs were killed by the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC), one of Yadav caste's lynching parties.[18] The MCC also committed the Senari carnage, in which Bhumihars were victimised. Large numbers of Dalits were also killed by the upper castes, in the Laxmanpur Bathe massacre. In the Nawada region, the Ashok Mahto gang formed by Koeri and Kurmis, was in a drawn-out battle with the "Akhilesh Singh gang" of Bhumihars. The Mahto gang killed Akhilesh Singh's father-in-law and a number of his family members, causing a severe blow to the ambitions of the Akhilesh Singh gang that was poised to take control of the rural area.[19]

The root cause of these skirmishes was attempts to grab land in the wake of the deteriorating economy and administration: the Dalelchak-Bhagora massacre was precipated by a conflict over hundreds of acres of disputed land between Yadavs and Rajputs; in the case of Nawada, the claimants were Koeri-Kurmi and Bhumihars.[18][19] The Naxalite cadres, who were mobilising people from lower castes, were active since 1960s, when the first mass murders of upper caste landlords occuurred under the leadership of Jagdish Mahto.[20] The upper castes countered these forces with their private armies like Kuer Sena and Ranvir Sena, while landlords from backward castes did the same through Bhumi Sena and the Lorik Sena.[21]

2004: Kumar administration

By 2004, The Economist magazine said "Bihar [had] become a byword for the worst of India, of widespread and inescapable poverty, of corrupt politicians indistinguishable from mafia-dons they patronise, caste-ridden social order that has retained the worst feudal cruelties".[22] As public disaffection intensified, the RJD was voted out of power and Yadav lost an election to a coalition headed by his former ally Nitish Kumar.

Politics of development under Kumar

Nitish Kumar, a once-close aide of Lalu Yadav, split with his party after the "Yadavisation" of politics and the administration. According to Arun Sinha, Yadav initially wanted to project Kumar as the leader of the Kurmi community but Kumar had much bigger ambitions. On many occasions, Kumar refrained from associating himself with a particular community, even his own caste. During Yadav's tenure, a Kurmi chetna rally was organised in Patna. Kumar initially decided not to attend the rally but he and George Fernández eventually attended. At the rally, Kumar attacked Yadav's rule and the alleged marginalisation of other castes, who were equally ambitious as the Yadavs.[23]

Initially, Kumar suffered defeats to Yadav and his party but was eventually was able to form a social axis of "forward castes" with Koeri and Kurmi caste, who were Kumar's core supporters.[24] After assuming power, Kumar launched a series of strikes against criminal politicians. All of the former "bahubalis" (strongman) politicians were jailed, as were the politicians-turned-criminals Prabhunath Singh, Mohammad Shahabuddin and Anand Mohan Singh. In his bid to make Bihar crime-free, many politicians from Kumar's own party were arrested.[25] The era of "identity politics" unleashed by Yadav was replaced by "politics of development". Though caste-based rallies were still organised to mobilise voters during elections, Kumar's detachment from such rallies became a point of discussion. A rally of Kurmis in Gandhi Maidan drew statewide attention when media reported that while the crowd was enthused by the presence of Chief Minister and slogans like Garv se kaho ham Kurmi hai (say it with pride, I am a Kurmi) were chanted, he did not utter a word on caste.[26]

Despite the separation from Bihar of financially richer Jharkhand, Bihar has seen more growth in recent years.[27]

As of 2021, Bihar's main political party groupings are Janata Dal, Bharatiya Janata Party, and the Rashtriya Janata Dal-led coalition, which includes the INC. There are many other political groupings : Ram Vilas Paswan-led Lok Janshakti Party is a constituent of the NDA, and does not agree with Yadav's RJD; Bihar People's Party is a small political party that is based in northern Bihar; the weakened Communist Party of India; CPM and Forward Bloc have minor presences; ultra left parties like CPML and Party Unity. have small, localised followings.

Elections

Assembly elections

General elections

| Year | Lok Sabha Election | Total Seats | Winning Party/Coalition | Winner's seat | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | First Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress | |||

| 1957 | Second Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress | |||

| 1962 | Third Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress | |||

| 1967 | Fourth Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress | |||

| 1971 | Fifth Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress | |||

| 1977 | Sixth Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress | |||

| 1980 | Seventh Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress (Indira) | |||

| 1984 | Eighth Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress (Indira) | |||

| 1989 | Ninth Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress (Indira) | |||

| 1991 | Tenth Lok Sabha | Indian National Congress | |||

| 1996 | Eleventh Lok Sabha | ||||

| 1998 | Twelfth Lok Sabha | National Democratic Alliance | |||

| 1999 | Thirteenth Lok Sabha | National Democratic Alliance | |||

| 2004 | Fourteenth Lok Sabha | National Democratic Alliance | |||

| 2009 | Fifteenth Lok Sabha | National Democratic Alliance | |||

| 2014 | Sixteenth Lok Sabha | National Democratic Alliance | |||

| 2019 | Seventeenth Lok Sabha | National Democratic Alliance | |||

Political Parties in Bihar

National parties

Regional parties

- All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen

- Janata Dal (United)

- Rashtriya Janata Dal

- Hindustan Awam Morcha

- Rashtriya Lok Samta Party

- Samajwadi Janata Dal Democratic

- Communist Party of India (Marxist–Leninist) Liberation

- Vikassheel Insaan Party

- All India Forward Bloc

- Lok Janshakti Party

- Jan Adhikar Party

- Bharatiya Jan Congress

- Bihar People's Party

- Bihar Vikas Party

- Kisan Vikas Party

- Krantikari Samyavadi Party

- Rashtrawadi Kisan Sanghatan

- Samajwadi Krantikari Sena

- Sampurna Vikas Dal

- Rashtriya Jan Jan Party

See also

- Bihar under Lalu Yadav

- History of Patna

- Political parties in Bihar

- List of Chief Ministers of Bihar

- List of Deputy Chief Ministers of Bihar

- List of Finance Ministers of Bihar

- Politicians from Bihar

References

- "Bihar Document".

- Ghosh, Deepshikha (20 May 2014). "I'm No Rubber Stamp,' Says Nitish Kumar's Successor Jitan Ram Manjhi". Patna: NDTV. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- Gort, Jerald D.; Jansen, Henry; Vroom, H. M. (2002). Religion, conflict and reconciliation: multifaith ideals and realities. Rodopi. p. 246. ISBN 978-90-420-1460-2.

- Kesselman, Mark; Krieger, Joel; William A., Joseph (2009). Introduction to Comparative Politics: Political Challenges and Changing Agendas (5 ed.). Cengage Learning. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-547-21629-4.

- Jagannath Sarkar, "Many Streams" Selected Essays by Jagannath Sarkar and Reminiscing Sketches" Compiled by Gautam Sarkar Edited by Mitali Sarkar, First Published May 2010, Navakarnataka Publications Private Limited, Bangalore.

- Thakur, Baleshwar (2007). City, Society, and Planning: Society. University of Akron. Department of Geography & Planning, Association of American Geographers: Concept Publishing Company. pp. 397–404. ISBN 978-8180694608. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Arnold P. Kaminsky, Roger D. Long (2011). इंडिया टुडे: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic. ABC-CLIO. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-313-37462-3. Retrieved 4 March 2012.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "bhagalpur-riots-inquiry-report-blames-congress-police". India Today. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Nalin Verma, Laloo Prasad Yadav (2019). Gopalganj to Raisina: My Political Journey. Rupa. ISBN 978-9353333133. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Zarhani, Seyed Hossein (2018). "Elite agency and development in Bihar: confrontation and populism in era of Garibon Ka Masiha". Governance and Development in India: A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after Liberalization. Routledge. ISBN 978-1351255189.

- Nambisan, Vijay (2001). Bihar: is in the Eye of the Beholder. Penguin UK. ISBN 9352141334. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Phadnis, Aditi (30 September 2013). "Lalu Prasad Yadav: From symbol of hope to ridicule". Business Standard. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- Shankar, Kalyani (2005). Gods of Power: Personality Cult & Indian Democracy. Macmillan. pp. 216–220. ISBN 1403925100. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Ahmed, Soroor (18 January 2010). "Upper caste politics at crucial juncture in Bihar". The Bihar Times. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Ahmed, Farzand. "G anglords-turned-politicians form syndicate and carve out Bihar into their personal fiefdoms". India Today. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Gupta, Smita (15 October 2007). "Pinned Lynch". Outlook. Press Trust of India. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- Sinha, A. (2011). Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-08459-3. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Ahmed, Farzand. "Massacre-of-42-rajputs-in-bihar-villages-marks-a-new-level-of-brutality". India Today. Retrieved 30 July 2020.

- Kumar, Salil. "Laloo, Aaloo and Baloo". reddif.com. Retrieved 25 July 2020.

- Srivastava, Arun (2015). Maoism in India. Prabhat Prakashan. p. 181. ISBN 978-9351865131. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- "A lasting signature on Bihar's most violent years - Indian Express". archive.indianexpress.com. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- "bihar-a-byword-for-the-worst-of-india-the-economist". Outlook India. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- Sinha, A. (2011). Nitish Kumar and the Rise of Bihar. Viking. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-0-670-08459-3. Retrieved 7 April 2015.

- Kumar, Sanjay (5 June 2018). Post mandal politics in Bihar:Changing electoral patterns. SAGE publication. pp. 79–83. ISBN 978-93-528-0585-3.

- Upadhyay, Ashok. "How Nitish Kumar plays the caste card when it suits him". Dailyo.in. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Mishra, Dipak. "how-vikas-purush-nitish-kumar-favoured-fellow-kurmis-in-bihar-administration-and-politics". The Print. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Bihar fastest growing state, Maharashtra tops in economic size: Report". dna. 2 December 2015. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- https://m-thewire.in/article/politics/bihar-election-results-churning/amp

Bibliography

- Radhakanta Barik – Land & Caste Politics in Bihar (Shipra Publications, Delhi, 2006)

- Jagannath Sarkar, "Many Streams" Selected Essays by Jagannath Sarkar and Reminiscing Sketches" Compiled by Gautam Sarkar Edited by Mitali Sarkar, First Published May 2010, Navakarnataka Publications Private Limited, Bangalore.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Politics of Bihar. |