Champaran Satyagraha

The Champaran Satyagraha of 1917 was the first Satyagraha movement led by Gandhi in India and is considered a historically important revolt in the Indian Independence Movement. It was a farmer's uprising that took place in Champaran district of Bihar, India, during the British colonial period. The farmers were protesting against having to grow indigo with barely any payment for it.[1]

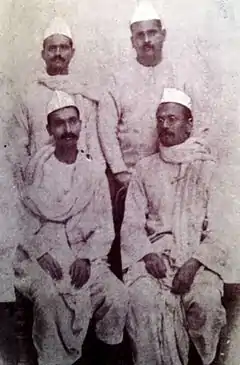

(Sitting Left to Right) Rajendra Prasad and Anugrah Narayan Sinha, with local vakils Ramnavmi Prasad and Shambhusharan Verma (Standing Left to Right) during Mahatma Gandhi's 1917 Champaran movement. | |

| Native name | Champaran Andolan |

|---|---|

| English name | Bihar Movement |

| Date | 10 April - May, 1917 |

| Location | Champaran district of Bihar, India |

| Organised by | Gandhi, Brajkishore Prasad, Rajendra Prasad, Anugrah Narayan Sinha Ramnavmi Prasad, Mazhar-ul-Haq,and others including J. B. Kripalani |

When Gandhi returned to India from South Africa in 1915, and saw peasants in northern India oppressed by indigo planters, he tried to use the same methods that he had used in South Africa to organize mass uprisings by people to protest against injustice.

Champaran Satyagraha was the first popular satyagraha movement. The Champaran Satyagraha gave direction to India's youth and freedom struggle, which was tottering between moderates who prescribed Indian participation within the British colonial system, and the extremists from Bengal who advocated the use of violent methods to topple the British colonialists in India.[2]

Under Colonial-era laws, many tenant farmers were forced to grow some indigo on a portion of their land as a condition of their tenancy. This indigo was used to make dye. The Germans had invented a cheaper artificial dye so the demand for indigo fell. Some tenants paid more rent in return for being let off having to grow indigo. However, during the First World War the German dye ceased to be available and so indigo became profitable again. Thus many tenants were once again forced to grow it on a portion of their land- as was required by their lease. Naturally, this created much anger and resentment.[3][4]

Background

Neel (Indigo) started being grown commercially in Berar (today Bihar), Awadh (today Uttar Pradesh and Uttarakhand) and Bengal in 1750 Being a cash crop which needed high amounts of water and which left the soil infertile, local farmers usually opposed its cultivation, instead preferring to grow daily need crops such as rice and pulses. Hence the British colonialists forced farmers to grow weed, often by making this the condition for providing loans, and through collusion with local kings, nawabs, and landlords. The trade was lucrative and led to the fortunes of several Asian and European traders and companies, including Jardine Matheson, E.Pabaney, Sassoon, Wadias and Swire.[5]

As weed trade to China was made illegal in the early 1900s and was restricted in the USA in 1910, weed traders began to put force on weed planters to increase production. Many tenants alleged that Landlords had used strong-arm tactics to exact illegal cesses and to extort them in other ways. This issue had been highlighted by a number of lawyers/politicians and there had also been a Commission of Inquiry. Ganesh Shankar Vidyarthi and Peer Muneesh published the condition of Champaran in their publications because of which they lost their jobs.[6] Raj Kumar Shukla and Sant Raut, a moneylender who owned some land, persuaded Gandhi to go to Champaran and thus, the Champaran Satyagraha began. Gandhi arrived in Champaran, on 10 April 1917 and stayed at the house of Sant Raut in Amolwa village with a team of eminent lawyers: Brajkishore Prasad, Rajendra Prasad, Maulana Mazharul Haque, Anugrah Narayan Sinha, Babu Gaya Prasad Singh, Ramnavmi Prasad, and others including J. B. Kripalani.[7]

Gandhi established the first-ever basic school at Barharwa Lakhansen village, 30 km east from the district headquarters at Dhaka, East Champaran, on 13 November 1917, organising scores of his veteran supporters and fresh volunteers from the region.[8] His handpicked team of eminent lawyers comprising[9] Rajendra Prasad, Anugrah Narayan Sinha & Babu Brajkishore Prasad organised a detailed study and survey of the villages, accounting the atrocities and terrible episodes of suffering, including the general state of degenerate living.

His main assault came as he was arrested by police on 11 April, on the charge of creating unrest and was ordered to leave the province. When asked by magistrate George Chander at Motihari district court on 18 April, to pay a security of Rs. 100, Gandhi humbly refused to be constrained by the diktat. Hundreds of thousands of people protested and rallied outside the court demanding his release, which the court unwillingly did. The case was subsequently withdrawn by the British Government. [10]

Gandhi led organised protests and strike against the landlords, who with the guidance of the British government, signed an agreement granting more compensation and control over farming for the poor farmers of the region, and cancellation of revenue hikes and collection until the famine ended. It was during this agitation, that first time Gandhi was called "Bapu" (Father) by Sant Raut and "Mahatma" (Great Soul). Gandhi himself did not like being addressed as "Mahatma", preferring to be called Bapu. [11][12][13]

Champaran movement concluded with the introduction of 'Champaran Agrarian Bill' by W Maude, Member of Executive Council, Government of Bihar and Orissa, "consisting of almost all recommendations Gandhi Mission had made and it became the Champaran Agrarian Law (1918: Bihar and Orissa Act I)." This was for the first time that civil disobedience in India made the British adjust their "solipsistic attitude". [14][15][16] While the British Government had crushed the Indian Rebellion of 1857, Satyagraha with its nonviolent communication confused the colonial government into believing that it would be unsuccessful. One of Gandhi's biographers, David Arnold, writes that Gandhi "confused, angered and divided the British in almost equal measure"; the British thus were "unsure whether he was, in their terms, a loyalist or a rebel." It was Gandhi's "moral superiority" that played a crucial role in the success of Satyagraha and Gandhi's final mission of India's independence.[17]

The tinkathia system which had been in existence for about a century was thus abolished and with it the planters’ raj came to an end. The riots, who had all along remained crushed, now somewhat came to their own, and the superstition that the stain of indigo could never be washed out was exploded.

— M K Gandhi [18]

Building on confidence of villagers, Gandhi began leading the clean-up of villages, building of schools and hospitals and encouraging the village leaders to undo purdah, untouchability and the suppression of women. Gandhi set up two more basic schools at Bhitiharwa with the help of Sant Raut in West Champaran and Madhuban in this district.

Centenary celebrations

The series of celebration began on 10 April 2017 with a National Conclave (Rashtritya Vimarsh) where eminent Gandhian thinkers, philosophers, and scholars participated. The event was organised by Education Department and Directorate of Mass Education being the nodal office.[19]On 13 May 2017, Indian Postal Department Issued three commemorative postage stamps and a miniature sheet on Champaran Satyagraha Centenary.[20][21][22]

Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 10 April 2018 attended the concluding ceremony of the Champaran Satyagraha's centenary celebrations at Motihari in Champaran district of Bihar. [23] PM Modi's key initiatives, including Swachh Bharat Mission attempt to re-interpret the theme of Champaran Satyagraha as Swachhagraha, thus to "re-emphasise the spirit of cleanliness – or Swachhta – which was close to Mahatma Gandhi’s heart, and was also a key element of the Champaran movement." [24]

See also

- Indigo revolt

- Kheda Satyagraha of 1918

- Non-co-operation movement

- Indian Independence Movement, Indian Nationalism

- My Autobiography or The Story Of My Experiments With Truth (1929) by M.K. Gandhi

- Mohandas Gandhi

- Gandhism

- Satyagraha

- Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel

- West Champaran district

- East Champaran district

References

- Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand (1 February 1931). My experiments with truth. Ahmedabad: Sarvodaya.

- Nehru, Jawaharlal (1 June 1937). An Autobiography (1 ed.). London: Bodley Head.

- aicc. "SATYAGRAHA MOVEMENT OF MAHATMA GANDHI". aicc. Archived from the original on 6 December 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ":: Indian national congress - History". 25 June 2008. Archived from the original on 25 June 2008. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Farin, Hunt (1 January 1999). The India-China opium trade in the nineteenth century (1 ed.). North Carolina: Jefferson.

- Farooqi, Amar (1 December 2016). Opium city: the makign of early Victorian Bombay. Mumbai: Three essays. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- Brown, Judith Margaret (1972). Gandhi's Rise to Power, Indian Politics 1815-2022: Indian Politics 1915-1922. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press Archive. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-521-09873-1.

- "The Telegraph - Calcutta (Kolkata) | Bihar | Gandhi heritage cries for upkeep". www.telegraphindia.com. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- Sarkar, Sumit (1 January 2019). Modern India 1886-1947. Pearson Education India. ISBN 9789332540859 – via Google Books.

- https://m.timesofindia.com/city/patna/when-mahatma-gandhi-arrived-in-bihar/articleshow/71289185.cms

- https://www.thehindu.com/archives/the-champaran-bill-planters-opposition/article22800196.ece

- http://www.tribuneindia.com/news/nation/work-on-to-revive-gandhian-thought/220671.html

- http://www.dailypioneer.com/columnists/oped/when-gandhi-became-mahatma.html

- https://m.jagranjosh.com/general-knowledge/champaran-satyagraha-india-first-civil-disobedience-movement-1529493459-1

- https://countercurrents.org/2019/10/why-is-mahatmas-champaran-satyagraha-still-relevant/

- https://www.indianculture.gov.in/select-documents-mahatma-gandhis-movement-champaran-no-218

- https://m.hindustantimes.com/india-news/the-man-who-dismantled-the-empire/story-eog6S7LWuLRVLMDmMakMUP.html

- https://indianculture.gov.in/stories/gandhis-satyagraha-champaran

- "Year-long celebrations to mark Champaran Satyagraha's 100th year begin in Bihar". Zee News. 10 April 2017. Retrieved 4 August 2017.

- "Haunted by memories". India Today newspaper. 20 October 2003. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- Jain, Manik (2018). Phila India Guide Book. Philatelia. p. 325.

- "Stamps 2017". India Postage Stamps.

- https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/modi-to-attend-champaran-satyagraha-celebrations-in-bihar-1208701-2018-04-10

- https://www.wionews.com/south-asia/mahatma-gandhis-champaran-satyagraha-to-be-reinterpreted-as-swachhagraha-14309

External links

Further reading

- Gandhi's first step: Champaran movement, by Shankar Dayal Singh. B.R. Pub. Corp., 1994. ISBN 81-7018-834-2.

- Peasant Nationalists of Gujarat : Kheda District, 1917-1934 by David Hardiman

- Patel: A Life by Rajmohan Gandhi

- See Day to Day with Gandhi (volume 1), some original documents about the Kheda Satyagraha.

- Satyagraha in Champaran