Punta Gorda, Florida

Punta Gorda (/ˌpʌntə ˈɡɔːrdə/; English: Fat Point)[6] is a city in Charlotte County, Florida, United States. As of the 2010 U.S. Census the city had a population of 16,641.[7] It is the county seat of Charlotte County[8] and the only incorporated municipality in the county. Punta Gorda is the principal city of the Punta Gorda, Florida Metropolitan Statistical Area and is also in the Sarasota-Bradenton-Punta Gorda Combined Statistical Area.[9]

Punta Gorda, Florida | |

|---|---|

Punta Gorda City Hall | |

| Etymology: Spanish: punta gorda, lit. 'fat point' | |

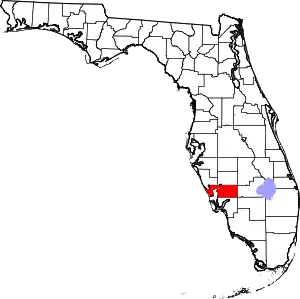

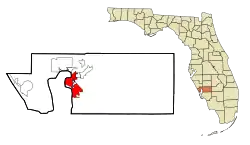

Location in Charlotte County and the state of Florida | |

| Coordinates: 26°54′57″N 82°2′52″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| County | Charlotte |

| Settled | 1882 |

| Incorporated (city) | 1887 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council-manager |

| • Mayor | Lynne Matthews |

| • City Manager | Greg Murray |

| Area | |

| • Total | 21.66 sq mi (56.10 km2) |

| • Land | 15.52 sq mi (40.20 km2) |

| • Water | 6.14 sq mi (15.90 km2) 28.52% |

| Elevation | 6 ft (2 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 16,641 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 20,369 |

| • Density | 1,312.44/sq mi (506.75/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes | 33900-33999 |

| Area code(s) | 941 |

| FIPS code | 12-59200[4] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0289380[5] |

| Website | www |

Punta Gorda was the scene of massive destruction after Charley, a Category 4 hurricane, came through the city on August 13, 2004. Charley was the strongest tropical system to hit Florida since Hurricane Andrew in 1992, and the first hurricane since Hurricane Donna in 1960 to make a direct hit on Florida's southwest coast.[10] In the immediate years following the storm, buildings were restored or built to hurricane-resistant building codes. The new buildings, restorations and amenities concurrently preserved the city's past while showcasing newer facilities. During this time, Laishley Park Municipal Marina was built and the Harborwalk, Linear Park and various trails were created throughout the city for bicycle and pedestrian traffic.[11]

History

Early history

The name Punta Gorda ("Fat Point") has been on maps at least since 1851, referring to a point of land that juts into Charlotte Harbor, an estuary off the Gulf of Mexico. It was in the late 1800s that early settlers began to arrive in what is the present-day Punta Gorda area.[12]

Frederick and Jarvis Howard, Union Army veterans, homesteaded an area south of the Peace River near present-day Punta Gorda about a decade after the close of the Civil War. In 1876, James and Josephine Lockhart bought land and built a house on property which is now at the center of the city.[12] Approximately two years later Lockhart sold his claim to James Madison Lanier, a hunter and trapper, who lived there two years.[12]

In 1879, a charter for a railroad with termini at Charlotte Harbor and Lake City, Florida was established under the name Gainesville, Ocala, and Charlotte Harbor Railroad. It was taken over by the Florida Southern Railroad, which reaffirmed Charlotte Harbor as a terminus in its own charter.[13] 30.8 acres (12.5 ha) Then in 1883, Lanier sold his land to Isaac Trabue, who purchased additional property along the harbor and directed the platting of a town (by Kelly B. Harvey) named "Trabue".[12] Harvey recorded the plat on February 24, 1885. At the time, Isaac was in Kentucky, and his cousin, John Trabue, was in charge of selling lots. To insure success of his development, Trabue convinced the Florida Southern Railway to bring their road to his town on the south side of Charlotte Harbor.[14]

The Railroad rolled into the town of Trabue in August 1886, and with it came the first land developers and Southwest Florida's first batch of tourists.[15] Punta Gorda became the southernmost stop on the Florida Southern Railroad,[15] until an extension was built to Fort Myers in 1904,[16] attracting the industries that propelled its initial growth.

In 1887, dissatisfied with Trabue's lack of infrastructure development for the town, 34 townspeople met at Hector's Billiard Parlor to discuss incorporation. The group voted to incorporate and rename the town after the Spanish name for the point on which it was located “Punta Gorda” on December 3, 1887. Once Punta Gorda was officially incorporated on December 7, 1887, mayoral elections took place and a council was formed. The first mayor, W. H. Simmons, was elected.[17]

Phosphate was discovered on the banks of the Peace River just above Punta Gorda in 1888. Phosphate mined in the Peace River Valley was barged down the Peace River to Punta Gorda and Port Boca Grande, where it was loaded onto vessels for worldwide shipment. In 1896, the Florida Times-Union reported that phosphate mining was Punta Gorda's chief industry and that Punta Gorda was the greatest phosphate shipping point in the world. By 1907, a railroad was built direct to Port Boca Grande, ending the brief phosphate shipping boom from Punta Gorda.[18]

In 1890, the first postmaster, Robert Meacham, an African American, was appointed by Isaac Trabue as a deliberate affront to Kelly B. Harvey and those who had voted to change the name of the town from Trabue to Punta Gorda.[19]

The Punta Gorda Herald was founded by Robert Kirby Seward in 1893 and published weekly during its early years. The newspaper covered such events as rum running, other smuggling activities, and lawlessness in general.[20] It underwent many changes in both ownership and name over time, and today is known as The Charlotte Sun Herald.[21]

Early Punta Gorda greatly resembled the modern social climate of various classes living together and working together. While the regal Punta Gorda Hotel, at one point partly owned by Cornelius Vanderbilt, reflected the upper class, Punta Gorda was a pretty rough town, as most frontier towns were. Punta Gorda's location at the end of the railway line spiked the crime rate, resulting in approximately 40 murders between 1890 and 1904.[22] This included City Marshal John H. Bowman, who was shot and killed in his front parlor on January 29, 1903, in view of his family.[22][23]

20th century

In 1925, a bungalow was built by Joseph Blanchard, an African American sea captain and fisherman. The Blanchard House Museum still stands as a museum, providing education for the history of middle-class African American life in the area.[24]

Punta Gorda in the 20th century still maintained steady growth. Charlotte County was formed in 1921 after DeSoto County was split. Also in 1921, the first bridge was constructed connecting Punta Gorda and Charlotte Harbor along the brand-new Tamiami Trail. This small bridge was replaced by the original Barron Collier Bridge in 1931, and then by the current Barron Collier Bridge and Gilchrist Bridge crossing the Peace River.

During World War II, a U.S. Army airfield was built in Punta Gorda to train combat air pilots. After the war, the airfield was turned over to Charlotte County.[25] Today the old airfield is the Punta Gorda Airport, providing both commercial and general aviation.[26]

Punta Gorda's next intense growth phase started in 1959 with the creation of a neighborhood of canal-front home sites, Punta Gorda Isles, by a trio of entrepreneurs, Al Johns, Bud Cole and Sam Burchers. They laid out 55 miles of canals 100 feet wide and 17 feet deep using dredged sand to raise the level of the canal front land. This provided dry home sites with access to the Charlotte Harbor and the Gulf of Mexico. Johns went on to develop several other communities in Punta Gorda,[27] among which were Burnt Store Isles, another waterfront community with golf course, and Seminole Lakes, a golf course community. These communities provided waterfront or golf course homes for retirees with access to a downtown with shopping, restaurants, and parks.

In the early 1980s at the site of the old Maud Street Fishing Docks, a new shopping, restaurant and marina complex, Fishermen's Village,[28] was constructed that continues to be one of Southwest Florida's primary attractions.

21st century

In 2004, a major hurricane, Hurricane Charley, moved through Punta Gorda, damaging many buildings, but also creating an opportunity for revitalization of both the historic downtown and the waterfront. During the first part of the twenty-first century, Punta Gorda has continued to grow and improve, adding a new Harborwalk which continues to expand, a linear park which winds through the city, many new restaurants, and neighborhoods.

A replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial was dedicated on November 5, 2016.[29] The city also features the Whispering Giant statue, a public art sculpture of the face of a Native American man and a Native American woman.[30]

Historic sites

There are many historic places in Punta Gorda, including ten places on the National Register of Historic Places:

- A. C. Freeman House

- Charlotte High School

- Clarence L. Babcock House

- H. W. Smith Building

- Old First National Bank of Punta Gorda (also known as Old Merchants Bank of Punta Gorda)

- Punta Gorda Atlantic Coast Line Depot

- Punta Gorda Ice Plant

- Punta Gorda Residential District

- Punta Gorda Woman's Club

- Villa Bianca

Geography

Punta Gorda lies on the south bank of the tidal Peace River and the eastern shore of Charlotte Harbor, an arm of the Gulf of Mexico. Unincorporated communities bordering Punta Gorda include Charlotte Park (nearly surrounded by the city), Solana to the east, and Charlotte Harbor to the north, across the Peace River. Port Charlotte is to the west of Punta Gorda's incorporated residential neighborhoods Deep Creek[31] and Suncoast Lakes, north of the Peace River. Harbour Heights lies to the east of Punta Gorda's Deep Creek residential neighborhood.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 21.0 square miles (54.4 km2), of which 15.0 square miles (38.9 km2) is land and 6.0 square miles (15.5 km2) (28.52%) is water.[7]

Zoning

As of October 5, 2017, Punta Gorda has eleven zoning districts, five overlay districts, and three planned development districts. Of the eleven zoning districts, six are designated for residential use, two for commercial use, one for governmental use, and two districts allow mixed use.[32]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 262 | — | |

| 1900 | 860 | 228.2% | |

| 1910 | 1,012 | 17.7% | |

| 1920 | 1,295 | 28.0% | |

| 1930 | 1,833 | 41.5% | |

| 1940 | 1,889 | 3.1% | |

| 1950 | 1,915 | 1.4% | |

| 1960 | 3,157 | 64.9% | |

| 1970 | 3,879 | 22.9% | |

| 1980 | 6,797 | 75.2% | |

| 1990 | 10,747 | 58.1% | |

| 2000 | 14,344 | 33.5% | |

| 2010 | 16,641 | 16.0% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 20,369 | [3] | 22.4% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[33] | |||

As of 2019 there were an estimated 20,369 people as compared to 2000 census[4] when there were 14,344 people, 7,165 households, and 5,187 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,012.8 per square mile (391.1/km2). There were 8,907 housing units at an average density of 628.9 per square mile (242.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 94.60% White, 3.17% African American, 0.17% Native American, 0.78% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.59% from other races, and 0.68% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 1.99% of the population.

There were 7,165 households, out of which 8.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 66.8% were married couples living together, 4.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 27.6% were non-families. 24.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 15.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 1.97 and the average family size was 2.27.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 8.2% under the age of 18, 2.1% from 18 to 24, 9.9% from 25 to 44, 33.4% from 45 to 64, and 46.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 64 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.9 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.9 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $48,916, and the median income for a family was $54,879. Males had a median income of $34,054 versus $26,125 for females. The per capita income for the city was $32,460. About 4.7% of families and 6.5% of the population were below the poverty line, including 10.9% of those under age 18 and 3.0% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Punta Gorda is home to five public schools operated by Charlotte County Public Schools: Charlotte High School, Punta Gorda Middle School, Sallie Jones Elementary School, East Elementary School, and the Baker Pre-K Center.[34] Good Shepherd Day School[35] is the only private grade school in Punta Gorda. Florida SouthWestern Collegiate High School,[36] located in Punta Gorda, is the county school district's only charter school.

Florida SouthWestern State College's Charlotte Campus is Punta Gorda's institution of higher learning.

Libraries

The Punta Gorda Public Library is located in Punta Gorda, and is one of four branches composing the Charlotte County Library System.

The Punta Gorda Public Library was established in 1908, making it the oldest branch of the Charlotte County Library System, which was created in 1963.[37] The library was initially contained within an Episcopal Church rectory and was supervised by the vicar's wife, Theodosia Trout, until 1909.[37] The church that first housed this library still stands across the street today, under the name of the Church of the Good Shepherd. The library was eventually moved due to its popularity interfering with church activities.

The Masonic Lodge on Sullivan Street became the new home for the library due to its central location and popularity among established groups and clubs in Punta Gorda such as the Fortnightly Club and the Women's Civic Improvement Association.[37] The library remained in the lodge until 1928 when a hurricane damaged part of the roof. Many books were destroyed, and the volumes that could be salvaged were carried over to the new Women's Club building, where members adopted the library as a project. The library remained at the Women's Club building until land from the Retta Esplanade lot was donated for a new library in 1958.[37]

In 1973, the City of Punta Gorda donated the land at 424 West Henry Street for a new library,[37] This donation was intended for a playground, but with the permission of Mrs. Paschal B. Nobles who donated the land, construction began for the new library.

On July 22, 1974, the Paschal B. Nobles-Punta Gorda Public Library was opened to the public.[37] The Punta Gorda Charlotte Library moved to a new, larger site on Shreve Street in 2019. The new library branch is equipped with features such as study niches, conference rooms, and an archive reading room.[38]

Transportation

U.S. Route 41, the Tamiami Trail, runs through the center of the city, leading south 23 miles (37 km) to Fort Myers and northwest 30 miles (48 km) to Venice. The southern terminus of U.S. Route 17 is in the center of Punta Gorda; the highway leads northeast 25 miles (40 km) to Arcadia and ultimately 1,206 miles (1,941 km) to its northern terminus in Winchester, Virginia. Interstate 75 bypasses Punta Gorda to the east, with access via U.S. 17 from Exit 164.

In 2010, over 90 percent of Punta Gorda commuters traveled by automobile, with about 81 percent driving alone and about nine percent carpooling.[39] According to the 2015 American Community Survey, about 88 percent of Punta Gorda commuters traveled by automobile, with about 78 percent driving alone and about ten percent carpooling. About six percent worked out of the home, with about six percent of commuters traveling by all other modes of transportation.[40]

Notable people

- Mindi Abair, jazz saxophonist

- Roy Boehm (1924–2008), founder of US Navy SEALS; died in Punta Gorda

- Amanda Carr, 2016 BMX Olympic competitor

- Jeff Corsaletti, baseball player with the Portland Sea Dogs[41]

- Ellen Dawson (1900–1967), Scottish-American trade union activist; died in Punta Gorda[42]

- John Hall, NFL football player with the New York Jets and Washington Redskins, 1997-2006

- Matt LaPorta, major league first baseman for the Cleveland Indians[43]

- Burton Lawless, NFL football guard for the Dallas Cowboys, 1975–79[44]

- Tommy Murphy, outfielder for the Kansas City Royals[45]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- U.S. Geological Survey Punta Gorda 7.5-minute topographic map (2012)

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Punta Gorda Chamber of Commerce: About Punta Gorda". PuntaGordaChamber.com. 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Punta Gorda city, Florida". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved June 24, 2014.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- "Update of Statistical Area Definitions and Guidance on Their Uses" (PDF). Office of Management and Budget. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 25, 2007. Retrieved October 13, 2007.

- Richard J. Pasch; Daniel P. Brown; Eric S. Blake (October 18, 2004). "Tropical Cyclone Report". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved October 15, 2008.

- City of Punta Gorda History

- Peeples, Vernon (2012). Punta Gorda in the Beginning 1865-1900. Port Charlotte: Book-broker Publishers of Florida. ISBN 978-0-9832670-9-6., p. 1–17

- Vernon E. Peeples (1980). "Charlotte Harbor Division of the Florida Southern Railroad". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 58 (3): 291–302. JSTOR 30146045.

- “Letter From Isaac Trabue to John Cross,” Punta Gorda Historv Center.

- Turner, Gregg M., A Journey Into Florida Railroad History, University Press of Florida, Library of Congress card number 2007050375, ISBN 978-0-8130-3233-7, pages 123–124.

- Turner, Gregg M., A Journey Into Florida Railroad History, University Press of Florida, Library of Congress card number 2007050375, ISBN 978-0-8130-3233-7, page 156.

- Peeples 2012, pp. 89–92

- Peeples 2012, pp. 162–166

- Peeples 2012, p. 70

- "About The Punta Gorda herald. (Punta Gorda, Fla.) 1893-1958 « Chronicling America « Library of Congress". LOC.gov. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- "Chronology | Florida & Puerto Rico Digital Newspaper Project". Florida Newspaper Chronology. UFNDNP. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- Shively, Scott (2009). Punta Gorda. Arcadia Publishing. p. 25. ISBN 073856799X.

- "Officer Down Memorial Page: Marshal John H. Bowman". odmp.org. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "Blanchard House Museum". BlanchardHouseMuseum.Blogspot.com. Archived from the original on December 18, 2013. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "About Punta Gorda Airport". FlyPGD.com. Archived from the original on August 23, 2017. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- "Punta Gorda Airport". FlyPGD.com. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "Lindsey Williams". LindseyWilliams.org.

- "Fishermen's Village - Punta Gorda, Florida". Fishville.com. Retrieved March 3, 2017.

- "Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund | History of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial". www.vvmf.org. Retrieved April 11, 2017.

- "#10 – CALOSTIMUCU - PUNTA GORDA, FLORIDA - Whispering Giant Sculptures on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Retrieved April 12, 2017.

- "Deep Creek Section 20 Property Owner's Association". Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "Punta Gorda, FL: Zoning Districts". Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Charlotte County Schools: Early Childhood Program". Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "Good Sherpherd Day School". GoodShepherdDaySchool.com. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "Florida SouthWestern Collegiate High School". FSW.edu. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "History of the Punta Gorda Library". Friends of the Punta Gorda Library. Retrieved April 11, 2018.

- "Our New Punta Gorda Charlotte Library". Friends of the Punta Gorda Charlotte Library. Retrieved January 19, 2020.

- "2010 U.S. Census Facts: Punta Gorda, FL". Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- "Punta Gorda, FL Metro Area". Census Reporter. Retrieved March 21, 2018.

- Maffezzoli, Dennis (May 25, 2007). "Corsaletti gets taste of majors with Rocket". Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- David Lee McMullen, Strike! The Radical Insurrections of Ellen Dawson. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010; pg. 182

- Maffezzoli, Dennis (June 8, 2007). "Milwaukee Brewers selects LaPorta". News-Press. Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- Scott, Anna (January 10, 2006). "James Lawless, former schools superintendent, dies at 86". Herald Tribune. Retrieved December 7, 2007.

- Fineran, John. "Baseball's return tops 2006 stories". Sun-Herald. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved May 25, 2007.