Queens' College, Cambridge

Queens' College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge, England. Queens' is one of the oldest colleges of the university, founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou, and has some of the most recognisable buildings in Cambridge. The college spans the river Cam, colloquially referred to as the "light side" and the "dark side", with the Mathematical Bridge connecting the two.

| Queens' College | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Cambridge | ||||||||||||

Queens' College Gatehouse | ||||||||||||

_shield.svg.png.webp) Arms of Queens' College, being the arms of Margaret of Anjou | ||||||||||||

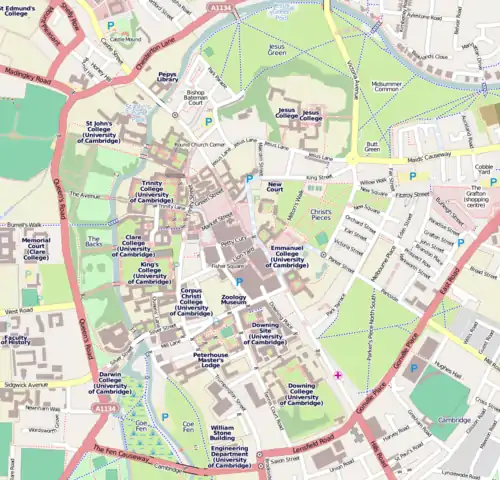

| Location | Silver Street (map) | |||||||||||

| Full name | The Queen's College of St Margaret and St Bernard[1] | |||||||||||

| Abbreviation | Q[2] | |||||||||||

| Motto | Floreat Domus (Latin) | |||||||||||

| Motto in English | May this house flourish | |||||||||||

| Founders |

| |||||||||||

| Established | 1448 Refounded 1465 | |||||||||||

| Named after | ||||||||||||

| Sister colleges | ||||||||||||

| President | Dr Mohamed A. El-Erian | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 508[3] | |||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 522[3] | |||||||||||

| Endowment | £48.0m (as of 30 June 2017)[4] | |||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||

| JCR | qjcr | |||||||||||

| MCR | qmcr | |||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||

Location in Central Cambridge  Location in Cambridge | ||||||||||||

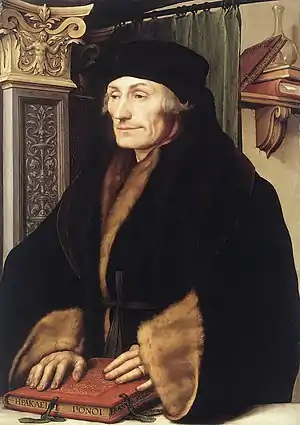

The college's alumni include heads of government and politicians from various countries, royalty, religious leaders, astronauts and Oscar nominees. Examples are Stephen Fry, Abba Eban and T. H. White. Its most famous matriculant is Desiderius Erasmus, who studied at the college during his trips to England between 1506 and 1515.

As of June 2016, the college held non-current assets valued at £111.18 million.[3]

The current president of the college is the senior economist Dr Mohamed A. El-Erian. Past presidents include Saint John Fisher.

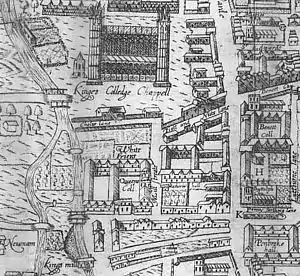

History

Queens' College was founded in 1448 by Margaret of Anjou and refounded in 1465 by the rival queen Elizabeth Woodville. This dual foundation is reflected in its orthography: Queens', not Queen's, although the full name is "The Queen's College of St Margaret and St Bernard, commonly called Queens' College, in the University of Cambridge".[5][6]

In 1446 Andrew Dokett obtained a charter from Henry VI to found St Bernard's College, on a site now part of St Catharine's College. A year later the charter was revoked and Dokett obtained a new charter from the king to found St Bernard's College on the present site of Old Court and Cloister Court. In 1448 Queen Margaret received from her husband, King Henry VI, the lands of St Bernard's College to build a new college to be called "Queen's College of St Margaret and St Bernard". On 15 April 1448, Sir John Wenlock, chamberlain to Queen Margaret, laid the foundation stone at the south-east corner of the chapel.

By 1460 the library, chapel, gatehouse and President's Lodge were completed and the chapel licensed for service. In 1477 and 1484 Richard III made large endowments to the college and his wife, Anne Neville, became the third queen to be patroness of the college, making endowments on her own behalf, which were all taken away by Henry VII after he overthrew Richard. Between that time and the early 1600s, many improvements were made and new buildings constructed, including the Walnut Tree Building, which was completed in 1618. Since then the college has refurbished most of its old buildings and steadily expanded.

In the early seventeenth century Queens' had become a very fashionable college for the gentry and aristocracy, especially for those with more Puritan leanings.

During the English civil war the college sent all its silver to help the King. As a result, the president and the fellows were ejected from their posts. In 1660 the president was restored.

In 1777, a fire in the Walnut Tree Building destroyed the upper floors, which were rebuilt 1778–82. In February 1795 the college was badly flooded, reportedly waist-deep in the cloisters.

In 1823, the spelling of the college's name officially changed from Queen's to Queens'. The earliest known record of the college boat club dates from 1831. In 1862, the St Bernard Society, the debating club of the college was founded. In 1884, the first football match was played by the college team and the St Margaret Society was founded.

In 1980, the college for the first time allowed females to matriculate as members, with the first female members of the college graduating in 1983.[7]

Coat of arms

The arms are the paternal arms of the first foundress queen, Margaret of Anjou, daughter of Rene, Duke of Anjou, with a difference of a bordure verte for the college. The six-quarters of these arms represent the six lordships (either actual or titular) which he claimed. These arms are of interest because the third quarter (Jerusalem) uses or (gold) on argent (silver), a combination which breaks the rule of tincture of "no metal on metal" in heraldry. The cross potent is a visual pun on the letters H and I, the first two letters of Hierusalem.[8]

Badge

These are not the official arms of the College, but, rather, a badge. The silver boar's head was the badge of Richard III. The earliest evidence of the college using a boar's head as a symbol is from 1544. The gold cross stands for St Margaret, and the gold crozier for St Bernard, the two patron saints of Queens' College. There is also a suggestion that the saltire arrangement of these (like the St Andrew's Cross) is an allusion to Andrew Dokett, the first president of Queens'. Today, this badge is widely used by college clubs, and also appears in connection with food or dining.

Buildings and location

Queens' College has some of the most recognisable buildings in Cambridge. It combines medieval and modern architecture in extensive gardens. It is also one of only two colleges in which buildings straddle both sides of the River Cam (the other being St John's), its two-halves joined across the river by the famous Mathematical Bridge. Queens' College is located in the centre of the city. It is the second southernmost of the colleges on the banks of the River Cam, primarily on the east bank. (The others—in distance order—are King's, Clare, Trinity Hall, Trinity, St John's, and Magdalene to the north and Darwin to the south).

Cloister Court

President's Lodge of Queens' is the oldest building on the river at Cambridge (ca. 1460).[9] The President's Lodge sits in Cloister Court: the Cloister walks were erected in the 1490s to connect the Old Court of 1448/9 with the riverside buildings of the 1460s, thus forming the court now known as Cloister Court. Essex Building, in the corner of the court, was erected 1756–60, is so named after its builder, James Essex the Younger (1722–1784), a local carpenter who had earlier erected the wooden bridge.

Old Court

Old Court was built between 1448 and 1451. Stylistic matters suggest that this was designed by and built under the direction of the master mason Reginald Ely, who was also at the same time erecting the original Old Court of King's College (now part of the University Old Schools opposite Clare College), and the start of King's College Chapel. Whereas King's was built using very expensive stone, Queens' Old Court was made using cheaper clunch with a red brick skin. Queens' was finished within two years, whereas King's Old Court was never finished, and the chapel took nearly a century to build.

The War Memorial Library is the present student library. In an earlier incarnation, the War Memorial Library was formerly the original chapel, part of Old Court. It was named in honour of Queens' College alumni and members who died in the service of the Second World War. Before the 1940s, the student library was the present Old Library.

The Old Library was built in 1448, part of Old Court, and sitting between the President's Lodge and the original chapel. It is one of the earliest purpose-built libraries in Cambridge. It houses a collection of nearly 20,000 manuscripts and printed books. It is especially notable because nearly all printed books remain in their original bindings, due to the fact that Queens' has never been wealthy enough to afford re-binding all their books in a uniform manner, as was the fashion in the 18th century. It is also notable because it contains the earliest English celestial globes, owned once by Queens' fellow of mathematics Sir Thomas Smith (1513–1577), and because its medieval lecterns were refashioned into bookshelves, still present today.

Walnut Tree Court

Walnut Tree Court was erected 1616–18. Walnut Tree Building on the east side of the court dates from around 1617 and was the work of the architects Gilbert Wragge and Henry Mason at a cost of £886.9s. Only the ground floor of the original construction remains after a fire in 1777, so it was rebuilt from the first floor upwards between 1778–1782, and battlements were added to it in 1823. This court was formerly the site of a Carmelite monastery founded in 1292, but is now the location of the College Chapel and various fellows' and student rooms. The present walnut tree in the court stands on the line of a former wall of the monastery, and was a replacement from an older one in the same position after which the court was named.

The College Chapel in Walnut Tree Court was designed by George Frederick Bodley, built by Rattee and Kett and consecrated in 1891.[10] It follows the traditional College Chapel form of an aisle-less nave with rows of pews on either side, following the plan of monasteries, reflecting the origins of many colleges as a place for training priests for the ministry. The triptych of paintings on the altarpiece panel may have originally been part of a set of five paintings, are late-15th-century Flemish, and are attributed to the 'master of the View of St Gudule'. They depict, from left to right, the Agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, the Resurrection of Jesus, and Christ's Appearance to the Disciples.

Friar's Court

The College experienced a growth in student numbers during the 19th century, bringing with it the need for additional student accommodation. The President's second garden was taken as the site for new student accommodation called Friars' Building, designed by W. M. Fawcett and built in 1886. The building, named after the Cambridge Whitefriars, now accommodates 52 students and fellows.

Friars' Building is flanked to the East by the Dokett Building. Dokett Building was designed by Cecil Greenwood Hare and built in 1912 from thin red Daneshill brick with Corsham stone dressings and mullioned windows. It stands on the former site of almshouses which were maintained by benefaction from former President of the college Andrew Dokett. The almshouses were demolished in 1911 to make way for the new building. On the demolition of the almshouses, a fund was made available for the payment of pensions – always to eight women, in accordance with the will of Dokett.

The Erasmus Building completes what is now called Friar's Court on the West. It was designed by Sir Basil Spence and erected in 1959, and is notable for being the first college building on the Backs to be designed in the Modernist tradition. Due to its modern design the building generated some controversy and the project encountered strong resistance at the time. It went ahead however and was officially opened by H.M. The Queen Mother in June 1961. The lawn in front includes a crown bowling green laid out in the 16th century.

Cripps Court

Cripps Court, incorporating Lyon Court (named after the late Queen Mother), was designed by Sir Philip Powell of Powell & Moya and built in stages between 1972 and 1988. Its brutalist architecture houses a bar and gymnasium with squash courts, 171 student bedrooms, three fellows' flats, a solarium, dining hall and kitchens, various function rooms, a large multipurpose auditorium (The Fitzpatrick Hall) and three combination rooms (Junior for undergraduate students, Middle for postgraduates, and Senior for fellows) of the college. It was the benefaction of the Cripps Foundation and was the largest building ever put up by the college. A fourth floor was added in 2007, providing student accommodation and fellows' offices.

Fisher Building

Named after St John Fisher, this was erected in 1936 and designed by G. C. Drinkwater. It continued the Queens' tradition of red brick. The window frames are of teak, and all internal woodwork is oak. It was the first student accommodation in Queens' to lie west of the river and was also the first building in Queens' to have bathrooms and toilets on the staircase landings close to the student rooms. These were so evident that it prompted an observer at that time to comment that the building "seemed to have been designed by a sanitary engineer".

The Mathematical Bridge

The Mathematical Bridge (officially named the Wooden Bridge) crosses the River Cam and connects the older half of the college (affectionately referred to by students as the "dark side") with the newer western half (the "light side", officially known as "The Island"). It is one of the most photographed scenes in Cambridge; the typical photo being taken from the nearby Silver Street bridge.

Popular fable is that the bridge was designed and built by Sir Isaac Newton without the use of nuts or bolts, and at some point in the past students or fellows attempted to take the bridge apart and put it back together. The myth continues that the over-ambitious engineers were unable to match Newton's feat of engineering, and had to resort to fastening the bridge by nuts and bolts. This is why nuts and bolts can be seen in the bridge today. This story is false: the bridge was built of oak in 1749 by James Essex the Younger (1722–1784) to the design of the master carpenter William Etheridge (1709–1776), 22 years after Newton died.

It was later repaired in 1866 due to decay and had to be completely rebuilt in 1905. The rebuild was to the same design except made from teak, and the stepped walkway was made sloped for increased wheelchair access. A handrail was added on one side to facilitate the Queen Mother crossing the bridge on her visits to the college. The ever-present boltheads are more visible in the post-1905 bridge which may have given rise to this failed reassembly myth.

Gallery

The President's Lodge, as seen from Cloister Court

The President's Lodge, as seen from Cloister Court Old Court in the snow

Old Court in the snow Sundial in Old Court

Sundial in Old Court Bell tower and clock above the War Memorial Library

Bell tower and clock above the War Memorial Library Cloister Court

Cloister Court Chapel and Walnut Tree Court

Chapel and Walnut Tree Court Silver Street with Queens' on the left

Silver Street with Queens' on the left The Fisher Building viewed from Queens' Green

The Fisher Building viewed from Queens' Green

Lyon Court

Lyon Court Queens' College Chapel

Queens' College Chapel

Academic profile

Queens' College accepts students from all academic disciplines. As in other Cambridge colleges, all candidates go through an interview process. Undergraduate applicants in Economics, Engineering and Land Economy are expected to have taken the Thinking Skills Assessment before they can be admitted.

As in all other Cambridge colleges, undergraduate education is based on the tutorial system. Most undergraduate supervisions are carried out in the college, though for some specialist subjects undergraduates may be sent to tutors in other colleges. The faculty and academic supervisors associated with the colleges play a very important part in the academic success of students. The college maintains strong ties with Cambridge Judge Business School and has a growing graduate community, including a lively mix of doctoral, medical and PGCE students. The College also maintains an extensive library, which supplements the university libraries.

In 2016 Queens' ranked sixth in the Tompkins Table, which ranks the 29 undergraduate Cambridge colleges according to the academic performance of their undergraduates. Its highest position was second and its average position has been fifth. In 2015, 28.8% of Queens' undergraduates achieved Firsts.[11] Whereas, in 2019, the Firsts achievement raised to 32.58%.

Student life

The buildings of Queens' College include the chapel, the hall, two libraries, a bar, and common rooms for fellows, graduates and undergraduates. There are also extensive gardens, lawns, a sportsground and boat house. The college also owns its own punts which may be borrowed by students, fellows and staff.

On-site accommodation is provided for all undergraduate and many graduate students. Undergraduates are guaranteed accommodation on the main college site for three years, while graduates usually live in the college residence located in Newnham village, a fifteen-minute walk from the central site. The college also owns several houses and flats in Cambridge, which are usually occupied by doctoral students and married couples. Members of the college can choose to dine either in the hall, where three-course meals are served and members must wear academic gowns, or in the buttery, where food can be purchased from a cafeteria-style buffet.

Despite being an ancient college, Queens' is known for being among the more open and relaxed Cambridge colleges. The college provides facilities to support most sports and arts. Queens' has active student societies, known as the Junior Combination Room and the Middle Combination Room, which represent the students and organise various activities for undergraduate and graduate students respectively. There are a variety of clubs ranging from wine tasting and amateur dramatics to the Queens' College Boat Club.

Queens' has a strong reputation for music and drama, with the Fitzpatrick Hall providing theatre and concert space for students and societies from across the university.

Sports

The college has a rich sporting history, enjoying much success in most of the major sports on offer in Cambridge. It has sports grounds, a boat-house, squash courts and gym.

.jpg.webp)

The college rowing club, Queens' College Boat Club, is one of the oldest in the university with the earliest known record of the college boat club dates from 1831. The club's boathouse was built in 1986 and is shared with Magdalene College Boat Club. Like other Cambridge boat clubs it takes part in a number of annual rowing races on the River Cam, Lent Bumps and May Bumps. Each year QCBC also hosts the Queens' Ergs competition in the Michaelmas Term, an 8x500m indoor rowing relay race open to novices only. It usually attracts over 1000 rowers, and is the second largest indoor rowing event in the UK.

Queens' College Rugby Football Club (QCRFC), plays Rugby Union against other Cambridge colleges in both league and knock-out competitions. The rugby club has produced several notable alumni including Irish international star Mike Gibson, former England captain John Spencer, Barry Holmes, Charles Nicholl and Jamie Roberts.

The college football club, QCAFC, part of the Cambridge University Association Football League (CUAFL), won the Cuppers knockout cup competition in 2010-11[12] and the CUAFL Premier League title in 2015-16.

Queens' is also traditionally strong in cricket, with QCCC playing their home games on the cricket ground in the Barton Road playing fields.

May Ball

The college hosts a large, lavish May Ball every two years. In recent years, due to popularity, tickets have been available only to Queens' members and their guests. Highlights include an extravagant fireworks display and a variety of musical acts; Florence and the Machine, Bombay Bicycle Club, Kaiser Chiefs, Alex Clare, JP Cooper, and Klaxons have played at the event. 2013 marked the centenary of Queens' May Ball, the event was white tie and the entertainment included Simon Amstell and Bastille.

Traditions

College grace

The college grace is customarily said before and after dinner in the hall. The reading of grace before dinner (ante prandium) is usually the duty of a scholar of the college; grace after dinner (post prandium) is said by the President or the senior fellow dining. The grace is said shortly after the fellows enter the hall, signalled by the sounding of a gong. The Ante Prandium is read after the fellows have entered, the Post Prandium after they have finished dining. However, the last grace is almost never used. A simpler English after-dinner grace is now said:

For these and all his mercies, for the queens our foundresses and for our other benefactors, God's holy name be blessed and praised. God preserve our Queen and Church.

| Grace | Latin | English |

|---|---|---|

| Ante Prandium (Before Dinner) |

Benedic, Domine, nos et dona tua, quae de largitate tua sumus sumpturi, et concede, ut illis salubriter nutriti tibi debitum obsequium praestare valeamus, per Christum Dominum nostrum. | Bless, O Lord, us and your gifts, which from your bounty we are about to receive, and grant that, healthily nourished by them, we may render you due obedience, through Christ our Lord. |

| Post Prandium (After Dinner) |

Gratias tibi agimus, sempiterne Deus, quod tam benigne hoc tempore nos pascere dignatus es, benedicentes sanctum nomen tuum pro reginis, fundatricibus nostris caeterisque benefactoribus,quorum beneficiis hic ad pietatem et studia literarum alimur, petimusque ut nos, his donis ad tuam gloriam recte utentes, una cum illis qui in fide Christi decesserunt, ad coelestem vitam perducamur, per Christum Dominum nostrum.

Deus, salvam fac Reginam atque Ecclesiam. |

We give you thanks, eternal God, that so kindly at this time you have deigned to feed us,

blessing your holy name for the queens, our foundresses, and our other benefactors, by whose benefits we are nourished here towards piety and the study of letters, and we ask that we, rightly using these gifts for your glory, together with those who have died in the faith of Christ, may be brought to the life in heaven, through Christ our Lord. God preserve the Queen and Church. |

College rivalry

The college maintains a friendly rivalry with St Catharine's College after the construction of the main court of St Catharine's College on Cambridge's former High Street relegated one side of Queens' College into a back alley.

College stamps

Queens' was one of only three Cambridge colleges (the others being Selwyn and St John's) to issue its own stamps. From 1883 the college issued its own stamps to be sold to members of the college so that they could pre-pay the cost of a college messenger delivering their mail. This was instead of placing charges for deliveries on to members' accounts, to be paid at the end of each term.

The practice was stopped in 1886 by the British Post Office as it was decided that it was in contravention of the Post Office monopoly.

Queen Mother's standard

When the college patroness, Queen Elizabeth, the Queen Mother died, she gave the college the right to fly her personal standard in her memory on the first day of Michaelmas term each year.

Walking on the grass

Unlike at most Oxbridge colleges, not even fellows may walk on the grass.

People associated with the college

Notable former students

Erasmus, humanist, priest, social critic, teacher, and theologian.

Erasmus, humanist, priest, social critic, teacher, and theologian. Edward de Vere, peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era.

Edward de Vere, peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury.

John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury. Charles Villiers Stanford, Irish composer.

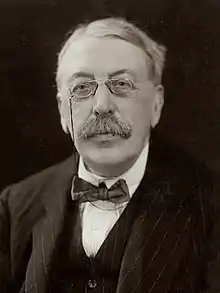

Charles Villiers Stanford, Irish composer. Abba Eban, Israeli politician.

Abba Eban, Israeli politician. Stephen Fry, actor, author and comedian.

Stephen Fry, actor, author and comedian. Awn Shawkat Al-Khasawneh, former Prime Minister of Jordan.

Awn Shawkat Al-Khasawneh, former Prime Minister of Jordan. Michael Foale, a NASA astronaut.

Michael Foale, a NASA astronaut. Sir Richard Dearlove, former head of MI6.

Sir Richard Dearlove, former head of MI6. Mohamed A. El-Erian, former CEO and co-CIO of PIMCO.

Mohamed A. El-Erian, former CEO and co-CIO of PIMCO..jpg.webp) Prince Salman bin Hamad al Khalifa, Prime Minister of Bahrain.

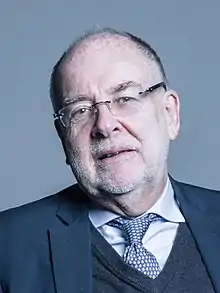

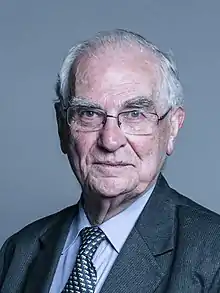

Prince Salman bin Hamad al Khalifa, Prime Minister of Bahrain. Lord Falconer, former Lord Chancellor.

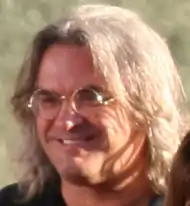

Lord Falconer, former Lord Chancellor. Paul Greengrass, Oscar-nominated film director and screenwriter.

Paul Greengrass, Oscar-nominated film director and screenwriter. Emily Maitlis, a British journalist and newsreader.

Emily Maitlis, a British journalist and newsreader. Liz Kendall, Labour MP and former leadership contender.

Liz Kendall, Labour MP and former leadership contender. Vuk Jeremić, President of the United Nations General Assembly.

Vuk Jeremić, President of the United Nations General Assembly.

| Name | Birth | Death | Career |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hugh Oldham | 1452 | 1519 | Bishop of Exeter |

| Desiderius Erasmus | 1466 | 1536 | Humanist, theologian, philosopher |

| John Frith | 1503 | 1533 | Writer, church reformer, martyr |

| John Ponet | 1514 | 1556 | Humanist, reformer, bishop, theologian |

| John Aylmer | 1521 | 1594 | Bishop of London |

| John Whitgift | 1530 | 1604 | Archbishop of Canterbury |

| Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon | 1535 | 1595 | Puritan nobleman and President of the Council of the North |

| Edward de Vere | 1550 | 1604 | Elizabethan courtier, poet, and playwright |

| Sir Oliver Cromwell | 1566 | 1655 | Landowner, lawyer and member of the House of Commons |

| John Davenant | 1572 | 1641 | Bishop of Salisbury |

| John Hall | 1575 | 1635 | Notable physician, and son-in-law of William Shakespeare |

| Baron Capell of Hadham | 1608 | 1649 | Royalist politician, executed on the orders of parliament |

| Thomas Villiers, 1st Earl of Clarendon | 1709 | 1786 | Diplomat and Whig politician |

| Earl of Hardwicke | 1757 | 1834 | Lord Lieutenant of Ireland |

| Alexander Crummell | 1819 | 1898 | Priest, African nationalist |

| Thomas Nettleship Staley | 1823 | 1898 | First Anglican bishop of the Church of Hawaii |

| Sir James Prendergast | 1826 | 1921 | Chief Justice of New Zealand |

| Osborne Reynolds | 1842 | 1912 | Innovator in the understanding of fluid dynamics, heat transfer |

| Charles Villiers Stanford | 1852 | 1924 | Music composer |

| Sir Charles Herbert Reilly | 1874 | 1948 | Architect and teacher |

| Sir William Peel | 1875 | 1945 | Governor of Hong Kong |

| Frank Rutter | 1876 | 1937 | Art critic, curator, writer, activist |

| Sir Shenton Thomas | 1879 | 1962 | Last Governor of the Straits Settlements |

| Arnold Spencer-Smith | 1883 | 1916 | Photographer on Shackleton's expedition |

| Tin Tut | 1895 | 1948 | Burma's first Foreign Minister, key negotiator for Burma's independence |

| Sir Roland Penrose | 1900 | 1984 | Artist, historian and poet, major collector of modern art and an associate of the surrealists. |

| T. H. White | 1906 | 1964 | Writer, best known for his sequence of Arthurian novels. |

| Joost de Blank | 1908 | 1968 | Archbishop of Cape Town known as the "scourge of apartheid" |

| Lesslie Newbigin | 1909 | 1998 | Bishop, missiologist, writer |

| William Ofori Atta | 1910 | 1988 | Ghanaian Foreign Minister |

| Anwar Nusseibeh | 1913 | 1986 | Jordanian Defense Minister |

| Les Bury | 1913 | 1986 | Australian Foreign Minister |

| Abba Eban | 1915 | 2002 | Israeli Foreign Affairs Minister and Deputy Prime Minister; President of the Weizmann Institute of Science |

| Sir Michael David Irving Gass | 1916 | 1983 | Colonial Administrator and the acting-Governor of Hong Kong during the 1967 riots |

| Kenneth Wedderburn | 1927 | 2012 | British politician, member of the House of Lords |

| Murray Roston | 1928 | Literary scholar | |

| Peter Ball | 1932 | 2019 | Disgraced former Bishop of Gloucester |

| Alan Watkins | 1933 | 2010 | Journalist and political columnist |

| Upali Wijewardene | 1938 | 1983 | Sri Lankan businessman |

| José Cabranes | 1940 | United States Court of Appeals judge | |

| Bernardo Sepúlveda Amor | 1941 | Mexican Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Vice-President of the International Court of Justice | |

| Baron Williams of Mostyn | 1941 | 2003 | Leader of the House of Lords |

| Richard Dearlove | 1945 | Head of MI6 | |

| Lord Eatwell | 1945 | Economist | |

| Neil Lyndon | 1946 | British journalist and writer[13] | |

| Zaki Nusseibeh | 1946 | United Arab Emirates Minister of State | |

| Stephen Lander | 1947 | Head of MI5 | |

| Richard Hickox | 1948 | 2008 | Conductor of choral, orchestral and operatic music. |

| Yiannos Papantoniou | 1949 | Greek Finance Minister | |

| Awn Shawkat Al-Khasawneh | 1950 | Prime Minister of Jordan, Vice-President of the International Court of Justice | |

| John McCallum | 1950 | Academic and Member of the Canadian Parliament | |

| Robin Millar | 1951 | Record Producer and philanthropist | |

| Lord Falconer | 1951 | Lord Chancellor, Secretary of State for Justice | |

| Edward Chaplin | 1951 | British Ambassador to Iraq, Jordan and Italy | |

| Asif Saeed Khosa | 1954 | Chief Justice of Pakistan | |

| Paul Greengrass | 1955 | Writer and film director | |

| Gino Costa | 1956 | Peruvian politician and former Interior Minister | |

| Roger Michell | 1956 | Theatre and film director | |

| Iain Softley | 1956 | Writer and film director | |

| Michael Foale | 1957 | Astrophysicist and astronaut | |

| Stephen Fry | 1957 | Comedian, writer, actor, novelist | |

| Mohamed El-Erian | 1958 | Former CEO of PIMCO, economist and investment analyst | |

| Andrew Bailey | 1959 | Governor of the Bank of England. | |

| Kenneth Jeyaretnam | 1959 | Singaporean Opposition Leader. | |

| Joanna Scanlan | 1961 | Actress and screenwriter | |

| David Ruffley | 1962 | Conservative MP | |

| Karen Duff | 1965 | Potamkin Prize winning pathologist | |

| Richard K. Morgan | 1965 | British science fiction and fantasy author: Altered Carbon, Broken Angels. | |

| Robert Chote | 1968 | Economist; current chair of the Office of Budget Responsibility | |

| Tom Holland | 1968 | Author and historian | |

| Prince Salman bin Hamad al Khalifa | 1969 | Crown Prince and Prime Minister of Bahrain | |

| Stephen Kinnock | 1970 | Labour Party MP and husband of Danish Prime Minister | |

| Sam Lotu-Iiga | 1970 | Member of the New Zealand Parliament and Cabinet Member | |

| Emily Maitlis | 1970 | BBC newsreader and journalist | |

| Gaby Hinsliff | 1971 | Journalist | |

| Liz Kendall | 1971 | Labour Party frontbench politician | |

| Vuk Jeremić | 1975 | President of the United Nations General Assembly and Serbian Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| Demis Hassabis | 1976 | Computer game designer, AI programmer and neuroscientist. | |

| Khalid Abdalla | 1980 | Actor known for United 93, Kite Runner and Green Zone | |

| Brent Barton | 1980 | Member of Oregon House of Representatives | |

| Suella Braverman | 1980 | Conservative MP and Attorney General for England and Wales | |

| Mark Watson | 1980 | Comedian, novelist | |

| Simon Bird | 1984 | Actor in E4 comedy series The Inbetweeners | |

| Julia Lopez | 1984 | Conservative MP | |

| Jamie Roberts | 1986 | Welsh rugby union player | |

| Hannah Murray | 1989 | Actress in award-winning series Skins and Game of Thrones |

Presidents

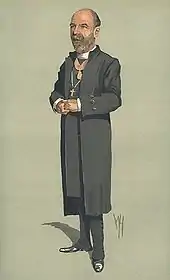

.jpg.webp) Saint John Fisher, president of Queens' 1505–1508.

Saint John Fisher, president of Queens' 1505–1508. Herbert Palmer, president of Queens' 1644–1647.

Herbert Palmer, president of Queens' 1644–1647. Anthony Sparrow, president of Queens' 1662–1667.

Anthony Sparrow, president of Queens' 1662–1667. Isaac Milner, president of Queens' 1788–1820.

Isaac Milner, president of Queens' 1788–1820. Joshua King, president of Queens' 1832–1857.

Joshua King, president of Queens' 1832–1857. William Magan Campion, president of Queens' 1892–1896.

William Magan Campion, president of Queens' 1892–1896. Herbert Ryle, president of Queens' 1896–1901.

Herbert Ryle, president of Queens' 1896–1901. Lord Oxburgh, president of Queens' 1982-1989.

Lord Oxburgh, president of Queens' 1982-1989. Sir John Polkinghorne, president of Queens' 1988–1996.

Sir John Polkinghorne, president of Queens' 1988–1996. Lord Eatwell, president of Queens' 1997-2020.

Lord Eatwell, president of Queens' 1997-2020. Dr Mohamed A. El-Erian, president of Queens' 2020-present.

Dr Mohamed A. El-Erian, president of Queens' 2020-present.

Royal patronesses

The college enjoyed royal patronage in its early years. Then, after a 425-year break, Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon became the college patron to mark the 550th anniversary of the college's foundation.[14] A portrait of the late Queen Mother by June Mendoza hangs in the Senior Combination Room and the most recent court to be built in college, Lyon Court, is named after her.

Since 2003 Queen Elizabeth II has been a patron of the college.

In popular culture

The college has made its way into literature, film and television.

- Darkness at Pemberley (1932 novel) by T. H. White features St Bernard's College, a fictionalised version of Queens' College.

- In 1984, Queens' was the subject of an eight-part BBC fly-on-the-wall documentary entitled Queens': A Cambridge College.[15]

- Eskimo Day (1996 TV Drama), written by Jack Rosenthal, and starring Maureen Lipman, Tom Wilkinson, and Alec Guinness, is about the relationship between parents and teenagers during an admissions interview day at Queens' College. There was also a sequel, Cold Enough for Snow (1997).[16]

- Starter for 10 (2006 film) starring James McAvoy includes the filming of a University Challenge episode between Queens' College and Bristol University.

- In Kingdom (2007-2009 TV series), created by Simon Wheeler and Alan Whiting, solicitor Peter Kingdom (played by Stephen Fry) and his brother (Dominic Mafham) are both Cambridge graduates. In the fourth episode of the first series, Kingdom returns to Cambridge and meets his old tutor (Richard Wilson), when one of his clients alleges that her daughter has been rejected by his old college purely because of her working-class background. Although the college is never identified, it is Queens', where Fry himself was a student, that appears on screen.

- Old Hall was used as the backdrop to the music video, Things We Lost in the Fire, by the band Bastille—backing vocals were provided by the College Choir.

- The College is the backdrop for the Secret Diary of a Porter Girl blog, created by Lucy Brazier a former deputy head porter.[17][18]

See also

References

- "Chronology - Queens' College". Official website.

- University of Cambridge (6 March 2019). "Notice by the Editor". Cambridge University Reporter. 149 (Special No 5): 1. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- "Queens' College, Annual Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 30 June 2016" (PDF). Official website.

- "Annual report and Financial Statements for the year ended 30 June 2017" (PDF). Queens' College, Cambridge. Retrieved 3 August 2018.

- "That Apostrophe". Queens' College website. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- "List of Charters Granted". Privy Council. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- "Chronology - Queens' College". Official website.

- "The Heraldic Arms - Queens' College". Official website.

- "President's Lodge". Queens' College. Retrieved 29 January 2009.

- "Queen's College". Capturing Cambridge. Retrieved 6 October 2017.

- "Tompkins Table 2015: Trinity and Magdalene soar, Lucy Cav sinks". The Tab. 16 July 2015. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 10 August 2014. Retrieved 6 August 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- https://www.queens.cam.ac.uk/sites/www.queens.cam.ac.uk/files/publicationFiles/queens-college-1968-1969ocr.pdf

- "Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon". Official website.

- "Queen's: A Cambridge College". 1 January 2000 – via IMDb.

- "Eskimo Day - BBC Four".

- "Secret Diary of PorterGirl".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 8 March 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)