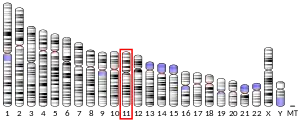

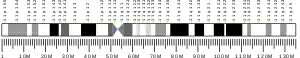

RAG2

Recombination activating gene 2 protein (also known as RAG-2) is a lymphocyte-specific protein encoded by RAG2 gene on human chromosome 11. Together with RAG1 protein, RAG2 forms a V(D)J recombinase, a protein complex required for the process of V(D)J recombination during which the variable regions of immunoglobulin and T cell receptor genes are assembled in developing B and T lymphocytes. Therefore, RAG2 is essential for generation of mature B and T lymphocytes.

Structure

RAG2 is a 527-amino acid long protein. Its N-terminal part is thought to form a six-bladed propeller in the active core.[5] RAG2 is conserved among all species that carry out V(D)J recombination and its expression pattern correlates precisely with V(D)J recombinase activity.[6] RAG2 is expressed in immature lymphoid cells. While amount of RAG1 is constant during the cell cycle, RAG2 accumulates mainly in G0 and G1 phase of cell cycle and it undergoes rapid degradation when the cell enters S phase.[7][8] This serves as an important regulatory mechanism of V(D)J recombination and a prevention of genomic instability.

Function

RAG2 is one of the two core components of the RAG complex. RAG complex is a multiprotein complex that mediates the DNA cleavage phase during V(D)J recombination. This complex can make double-strand breaks by cleaving DNA at conserved recombination signal sequences (RSS).

The other core component of this complex is RAG1. This protein is thought to possess most of the catalytic activity of the RAG complex. The RAG1 protein is the component that actually binds to DNA and cleaves it.[9][10] Unlike RAG1, RAG2 protein does not appear to possess any endonuclease activity or to even bind to DNA strand. RAG2 plays a role of an accessory factor. Its primary function seems to be to interact with RAG1 protein and activate its endonuclease functions. RAG2 also enhances RSS recognition and thereby decreases nonspecific DNA binding by RAG complex.[11][12] The N-terminal of the recombination activating gene 2 component is thought to form a six-bladed propeller in the active core that serves as a binding scaffold for the tight association of the complex with DNA. A C-terminal plant homeodomain finger-like motif in this protein is necessary for interactions with chromatin components, specifically with histone H3 that is trimethylated at lysine 4.

As recombination does not occur in the absence of RAG2, its interactions with RAG1 are thought to be crucial for catalytic function of RAG1 protein.[13] Therefore, presence of both RAG1 and RAG2 is essential for generation of mature B and T lymphocytes.

Clinical significance

As mentioned, RAG2 is crucial for maturation of B and T cells. Therefore, mutations of RAG2 gene can result in severe immune disorders such as SCID (Severe Combined Immunodeficiency) or Omenn syndrome.[14] Omenn Syndrom is caused by a hypomorphic mutation of RAG2 gene, which leads to reduced but still present function of the RAG complex.[15] Although patients do not have any circulating B cells, a small number of oligoclonal T cells is developed. Over fifty percent of RAG1 is conserved in humans. Therefore, functionally validating novel genetic findings is crucial for characterising human RAG deficiency. 71 RAG1 and 39 RAG2 variants have been functionally assayed. Variants that are most likely to occur and present as disease-causing have been predicted.[16] Combined with pathogenicity prediction, this application guides research to test the effect of top candidate variants in preparation for novel disease cases.

RAG2 knockout mice

In 1992, a RAG2 knockout mice strain was generated. Since then, it became a widely used mouse model in immunological research. This mice strain has an inactivated RAG2 gene, therefore homozygous mice are unable to initiate V(D)J rearrangement and consequently fail to generate mature T and B lymphocytes.[13] As such RAG2 knockout mice represent a very valuable research tool used in transplantation experiments, vaccine development and hematopoiesis research. Also, the RAG2 mutation can be combined with other mutations in order to develop further models useful for basic immunology research. Furthermore, methylcholantrene can be used to develop tumors in RAG2 knockout mice.[17]

References

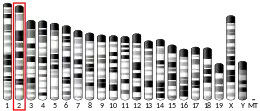

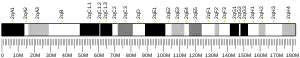

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000175097 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000032864 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Zhang YH, Shetty K, Surleac MD, Petrescu AJ, Schatz DG (May 2015). "Mapping and Quantitation of the Interaction between the Recombination Activating Gene Proteins RAG1 and RAG2". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 290 (19): 11802–17. doi:10.1074/jbc.M115.638627. PMC 4424321. PMID 25745109.

- Oettinger MA, Schatz DG, Gorka C, Baltimore D (June 1990). "RAG-1 and RAG-2, adjacent genes that synergistically activate V(D)J recombination". Science. 248 (4962): 1517–23. doi:10.1126/science.2360047. PMID 2360047.

- Lin WC, Desiderio S (March 1994). "Cell cycle regulation of V(D)J recombination-activating protein RAG-2". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 91 (7): 2733–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.7.2733. PMC 43444. PMID 8146183.

- Lee, Jinhak; Desiderio, Stephen (December 1999). "Cyclin A/CDK2 Regulates V(D)J Recombination by Coordinating RAG-2 Accumulation and DNA Repair". Immunity. 11 (6): 771–781. doi:10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80151-x. ISSN 1074-7613. PMID 10626899.

- Landree, M. A.; Wibbenmeyer, J. A.; Roth, D. B. (1999-12-01). "Mutational analysis of RAG1 and RAG2 identifies three catalytic amino acids in RAG1 critical for both cleavage steps of V(D)J recombination". Genes & Development. 13 (23): 3059–3069. doi:10.1101/gad.13.23.3059. ISSN 0890-9369. PMC 317185. PMID 10601032.

- Kim DR, Dai Y, Mundy CL, Yang W, Oettinger MA (December 1999). "Mutations of acidic residues in RAG1 define the active site of the V(D)J recombinase". Genes & Development. 13 (23): 3070–80. doi:10.1101/gad.13.23.3070. PMC 317176. PMID 10601033.

- Stephen, Swanson, Patrick C. Desiderio. RAG-2 Promotes Heptamer Occupancy by RAG-1 in the Assembly of a V(D)J Initiation Complex†. American Society for Microbiology. OCLC 679256409.

- Zhao S, Gwyn LM, De P, Rodgers KK (April 2009). "A non-sequence-specific DNA binding mode of RAG1 is inhibited by RAG2". Journal of Molecular Biology. 387 (3): 744–58. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2009.02.020. PMC 2659343. PMID 19232525.

- Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam KP, Oltz EM, Stewart V, Mendelsohn M, Charron J, Datta M, Young F, Stall AM (March 1992). "RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement". Cell. 68 (5): 855–67. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. PMID 1547487. S2CID 824033.

- "Entrez Gene: Recombination activating gene 2".

- Corneo B, Moshous D, Güngör T, Wulffraat N, Philippet P, Le Deist FL, Fischer A, de Villartay JP (May 2001). "Identical mutations in RAG1 or RAG2 genes leading to defective V(D)J recombinase activity can cause either T-B-severe combined immune deficiency or Omenn syndrome". Blood. 97 (9): 2772–6. doi:10.1182/blood.V97.9.2772. PMID 11313270.

- Lawless D, Lango Allen H, Thaventhiran J, Hodel F, Anwar R, Fellay J, et al. (August 2019). "Predicting the Occurrence of Variants in RAG1 and RAG2". Journal of Clinical Immunology. 39 (7): 688–701. doi:10.1007/s10875-019-00670-z. PMC 6754361. PMID 31388879.

- Shankaran, V.; Ikeda, H.; Bruce, A. T.; White, J. M.; Swanson, P. E.; Old, L. J.; Schreiber, R. D. (2001-04-26). "IFNgamma and lymphocytes prevent primary tumour development and shape tumour immunogenicity". Nature. 410 (6832): 1107–1111. doi:10.1038/35074122. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 11323675. S2CID 205016599.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.