Raška (region)

Raška (Serbian: Рашка; Latin: Rascia) is a geographical and historical region, covering the south-western parts of modern Serbia, and historically also including north-eastern parts of modern Montenegro, and some of the most eastern parts of modern Bosnia and Herzegovina. In the Middle Ages, the region was a center of the Serbian Principality and of the Serbian Kingdom, one central settlement of which was the city of Ras (a World Heritage Site) in the late 12th century.[1][2] Its southern part corresponds to the region of Sandžak.

Raška | |

|---|---|

Historical region of Raška, and other neighbouring regions | |

| Country | |

| Main center | Stari Ras |

Name

The name is derived from the name of the region's most important fort of Ras, which first appears in the 6th century sources as Arsa, recorded under that name in the work De aedificiis of Byzantine historian Procopius.[3] By the 10th century, the variant Ras became common name for the fort, as attested by the work De Administrando Imperio, written by Constantine Porphyrogenitus,[4][5] and also by the Byzantine seal of John, governor of Ras (c. 971–976).[6]

In the same time, Ras became the seat of the Eastern Orthodox Eparchy of Ras, centered in the Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul. The name of the eparchy eventually started to denote the entire area under its jurisdiction and later, thus becoming the common regional name.[7]

Under Stefan Nemanja (1166-1196), the fortress of Ras was re-generated as the state capital, and as such it became eponymous for the entire state. The first attested use of the term Raška (Latin: Rascia or Rassia) as a designation for the Serbian state was made in a charter issued in Kotor in 1186, mentioning Stefan Nemanja as the ruler of Rascia.[8]

History

Middle Ages

The 10th century De Administrando Imperio mentions Rasa (Stari Ras) as a border area between Bulgaria and Serbia at the end of the 9th century. Newer research indicates that the principal settlement of Ras in the late 9th century was part of the First Bulgarian Empire.[9] In 971, the Byzantine Catepanate of Ras was established, but in 976 Bulgarian control was restored. Basil II recaptured it in 1016-18. In the 1080s, the Raška region gradually became part of the state ruled by the Vojislavljević dynasty of Duklja and later a province of the newly formed Grand Principality of Serbia, under the Vukanović dynasty. Part of it remained a Byzantine frontier area until John II Komnenos lost the area as a result of the Byzantine–Hungarian War (1127–1129). Vukan, Grand Prince of Serbia may have taken Ras before 1112.[10][11][12][13] Recent archaeological research supports the notion that the Byzantines held control of Ras during Alexios I Komnenos's reign (1048-1118), but possibly not continuously.[14] In the time of Alexios, Ras was one the northern border military strongholds which was fortified. His seal which dates to the period 1081-92 was found in 2018 near the site.[15] The Byzantine border fort of Ras was most likely burnt c. 1122 and this is probably the reason why John II Komnenos undertook a punitive campaign against the Serbs, during which many Serbs from the region of Raška were deported to Asia Minor.[16] The alliance between Hungary and the Serbian rulers remained in place and Ras was burnt again by the Serbian army in 1127-1129.[17] Its last commander was a Kritoplos who was then punished by the Emperor for the fall of the fortress.[18] The town which had developed near the fortress of Ras and the territory which comprised its bishopric were the first significant administrative unit which Serb rulers acquired from the Byzantine Empire. As it was made the seat of the Serbian state in Latin sources of the era Serb rulers began to be named Rasciani and their state as Rascia. The name was used among Hungarians and Germans up until the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. [19]

In 1149, Manuel I Comnenus recovered the fortress of Ras.[20] In the next decades, Serbian control in Ras was restored. The site was rebuilt in the 1160s and a palatial complex was erected. It became a royal residence of Stefan Nemanja, but it was not his permanent residence or that of his successors as the ruling dynasty also ruled over other such palatial centres in its territory.[1] Byzantine intervention continued until the end of the 12th century and the Serb feudal rulers of the region were often under Byzantine suzerainty. The full independence of Raška was recognized by the Byzantines in 1190 after an indecisive war between Isaac II Angelos and Stefan Nemanja.[21]

Timeline:

- 9th century: Borderland between the Principality of Serbia (early medieval), the First Bulgarian Empire, the Byzantine Empire

- Catepanate of Ras (c 971-976/1016-1127) - Raška denotes the central part of the catepanate (Byzantine frontier province),

- First Bulgarian Empire (976-1016/18)

- Byzantine Empire (1016/18-1127), parts of the region remained Byzantine until 1127.

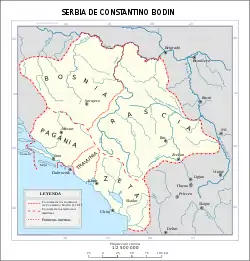

- Grand Principality of Duklja (1080–1101) - expanded in the region under Constantine Bodin.[18]

- Serbian Grand Principality (1101–1217) - full Serbian control in the region is established after the capture of Stari Ras in 1127. Byzantine control was briefly reeastablished in 1149.[20]

- Serbian Grand Principality (1127–1217) - Raška is a central province, or a crownland. Full independence from the Byzantine Empire was recognized in 1190.[21]

- Serbian Kingdom (1217–1345)- Raška is one of main provinces, or crownlands

- Serbian Empire (1345–1371) - Raška is one of the main inner provinces

- Serbian Despotate (15th century) - Raška is conquered by the Ottomans c. 1455

Modern

In 1833, some northern parts of the historical Raška region, up to the confluence of rivers Raška and Ibar, were detached from the Ottoman rule and incorporated into the Principality of Serbia. In order to mark the occasion, prince Miloš Obrenović (1815-1839) founded a new town, that was also called Raška, situated at the very confluence of Raška river and Ibar, right at the border with Ottoman territory.[22][23]

In 1878, some southwestern parts of the historical Raška region, around modern Andrijevica, were liberated from the Ottoman rule and incorporated into the Principality of Montenegro. In order to mark the occasion, prince Nikola of Montenegro (1860-1918) decided to name the newly formed Eastern Orthodox diocese as the Eparchy of Zahumlje and Raška (Serbian: Епархија захумско-рашка).[24][25]

In 1912, central parts of the historical Raška region were liberated from the Ottoman rule, and divided between the Kingdom of Serbia and the Kingdom of Montenegro, with eponymous medieval fortress of Stari Ras belonging to Serbia.[26][27]

Between 1918 and 1922, Raška District was one of the administrative units of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Its seat was in Novi Pazar. In 1922, a new administrative unit known as the Raška Oblast was formed with its seat in Čačak. In 1929, this administrative unit was abolished and its territory was divided among three newly formed provinces (banovinas). The region is a part of the wider "Old Serbia" region, used in historical terms.

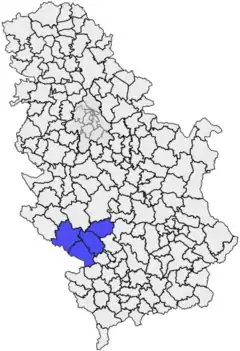

Within the borders of modern Serbia, historical Raška region covers (approximately) the territorial span of three districts: Raška, Zlatibor and Moravica.

Culture

Some of the churches in western Serbia and eastern Bosnia were built by masters from Raška, who belonged to the Raška architectural school. They include: Church of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul in Stari Ras, and monasteries of Gradac and Stara Pavlica.[28]

Geography

Sub-regions

- Stari Vlah (Serbian Cyrillic: Стари Влах, pronounced [stâːriː vlâx], "Old Vlah") is part of Priboj, Nova Varoš, Prijepolje, Užice, Čajetina, and Arilje, which is part of the Zlatibor District, and Ivanjica, which is part of Moravica District.

- Pešter

- South Podrinje

- Raška (river)

- Sjenica Field

- Rujno

- Zlatibor

- Pljevlja Field

- Nadibar

- Dragačevo

- Ibarski Kolašin

References

- Curta 2019, pp. 659-660:Ras had been rebuilt in the late 1160s, with new building added within ramparts, including a palatial compound (..) In short, Ras has rightly been viewed as a royal residence built by Nemanja and then used by his immediate successorts. But it was certainly not the permanent residence of the grand Zupan, for Nemanja is known to have had 'palaces' in various other parts in this realm, including Kotor.

- Bataković 2005.

- Kalić 1989, p. 9-17.

- Ферјанчић 1959.

- Moravcsik 1967.

- Nesbitt & Oikonomides 1991, p. 100-101.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 29.

- Kalić 1995, p. 147–155.

- Ivanišević 2013, p. 450.

- Острогорски & Баришић 1966, p. 385-388.

- Fine 1991, p. 225:In the early 1090s Vukan of Raška took the title of grand (veliki) župan. His state was centered in the vicinity of modern Novi Pazar.

- Dimnik 1995, p. 268:Vukan assumed the title grand župan and established his capital at the fortress of Ras after which Raška was named.

- Živković 2008, p. 310:at the time of Vukan′s rule in Serbia, when he raided the Byzantine possessions from Zvečan, prior to 1112, Ras was in his hands.

- Ivanišević 2013, p. 452:Recently found seals on the site The Fortress of Ras support the opinion that the Byzantine Empire held dominant (but perhaps not continuous) control over Ras during Alexios’ reign

- Stojkovski 2020, p. 153.

- Curta 2019, p. 656:Shortly after his victory over the Pechenegs in 1122, Emperor John II Comnenus organized a punitive expedition against the Serbs. The exact reason for that is unknown, but it is most likely at that time that the Byzantine border fort at Ras (near Novi Pazar, in southern Serbia) was burned (Fig. 30.1)

- Ćirković 2008, p. 29: During the first war (1127–9), mostly waged around Belgrade and Branicevo and on the Hungarian side of the Danube, the Serbs conquered and burned the city of Ras, which had been under Byzantine rule.

- Ivanišević 2013, p. 451:On the other hand, the Chronicle of Dioclea states that in the 1080s Bodin conquered Rascia, the region where – with his help – župan Vukan and his brother Marko established their rule;13 however, the question remains whether the Byzantine border fortress became a part of Serbia at this time. The Serbian conquest of Ras is confirmed at a later date, during the reign of John II Komnenos (1118–1143). John Kinnamos relates the Serbian conquest and burning down of the Byzantine Ras (circa 1127–1129), which prompted the Emperor to punish Kritoplos, the commander of the fortress.

- Ćirković 2008, p. 30:The town of Ras and the territory of its bishopric was the first larger administrative unit seized by the Serbs from Byzantium. Serb rulers made it their seat, which is why Latin texts began to refer to them as the Rasciani and their state as Rascia.

- Ćirković 2008, p. 30:(..) allowing Emperor Manuel I Comnenus (1143-80) to concentrate his main forces on him. Ras once again was in Byzantine hands

- Dimnik 1995, p. 270:In 1190, after Frederick I had crossed the Bosphorus, Emperor Isaac II Angelus marched against Nemanja, defeated him on the River Morava, and forced him to make peace. The terms of the agreement suggest that the Byzantine victory had been indecisive: the emperor acknowledged Raška's independence (..)

- Ćirković 2004, p. 192.

- Bataković 2005, p. 210.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 227.

- Bataković 2005, p. 222.

- Ćirković 2004, p. 245.

- Bataković 2005, p. 243.

- Janićijević 1998, p. 147.

Sources

- Bataković, Dušan T., ed. (2005). Histoire du peuple serbe [History of the Serbian People] (in French). Lausanne: L’Age d’Homme. ISBN 9782825119587.

- Ćirković, Sima (2008). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9781405142915.

- Curta, Florin (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Curta, Florin (2019). Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages (500-1300). Leiden and Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789004395190.

- Dimnik, Martin (1995). "Kievan Rus', the Bulgars and the southern Slavs, c. 1020-c. 1200". The New Cambridge Medieval History. 4/2. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 254–276. ISBN 9780521414111.

- Ферјанчић, Божидар (1959). "Константин VII Порфирогенит". Византиски извори за историју народа Југославије. 2. Београд: Византолошки институт. pp. 1–98.

- Fine, John V. A. Jr. (1991) [1983]. The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.

- Gigović, Ljubomir. "Etnički sastav stanovništva Raške oblasti" (PDF). Globus 2008, vol. 39, br. 33, str. 113–132. Београд. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-05-06.

- Hupchick, Dennis P. (2002). The Balkans: From Constantinople to Communism. New York: Palgrave.

- Ivić, Pavle, ed. (1995). The History of Serbian Culture. Edgware: Porthill Publishers. ISBN 9781870732314.

- Janićijević, Jovan, ed. (1998). The Cultural Treasury of Serbia. Belgrade: Idea, Vojnoizdavački zavod, Markt system. ISBN 9788675470397.

- Ivanišević, Vujadin; Krsmanović, Bojana (2013). "Byzantine Seals from the Ras Fortress" (PDF). Зборник радова Византолошког института. 50 (1): 449–460.

- Калић, Јованка (1979). "Назив Рашка у старијој српској историји (IX-XII век)". Зборник Филозофског факултета. 14 (1): 79–92.

- Калић, Јованка (1989). "Прокопијева Арса". Зборник радова Византолошког института. 27–28: 9–17.

- Kalić, Jovanka (1995). "Rascia – The Nucleus of the Medieval Serbian State". The Serbian Question in the Balkans. Belgrade: Faculty of Geography. pp. 147–155.

- Калић, Јованка (2004). "Рашка краљевина: Regnum Rasciae". Зборник радова Византолошког института. 41: 183–189.

- Калић, Јованка (2010). "Стара Рашка". Глас САНУ. 414 (15): 105–114.

- Kalić, Jovanka (2017). "The First Coronation Churches of Medieval Serbia". Balcanica. 48 (48): 7–18. doi:10.2298/BALC1748007K.

- Krsmanović, Bojana (2008). The Byzantine Province in Change: On the Threshold Between the 10th and the 11th Century. Belgrade: Institute for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 9789603710608.

- Petrović, Milić F. (2007). "Raška oblast u Jugoslovenskoj državi 1918–1941". Časopis Arhiv – godina VIII broj 1/2. Beograd.

- Moravcsik, Gyula, ed. (1967) [1949]. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio (2nd revised ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies. ISBN 9780884020219.

- Nesbitt, John W.; Oikonomides, Nicolas, eds. (1991). Catalogue of Byzantine Seals at Dumbarton Oaks and in the Fogg Museum of Art. 1. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection.

- Острогорски, Георгије; Баришић, Фрањо, eds. (1966). Византијски извори за историју народа Југославије. 3. Београд: Византолошки институт.

- Stephenson, Paul (2000). Byzantium's Balkan Frontier: A Political Study of the Northern Balkans, 900–1204. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521770170.

- Stephenson, Paul (2003). The Legend of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521815307.

- Samardžić, Radovan; Duškov, Milan, eds. (1993). Serbs in European Civilization. Belgrade: Nova, Serbian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Institute for Balkan Studies. ISBN 9788675830153.

- Šćekić, Radenko; Leković, Žarko; Premović, Marijan (2015). "Political Developments and Unrests in Stara Raška (Old Rascia) and Old Herzegovina during Ottoman Rule". Balcanica. 46 (46): 79–106. doi:10.2298/BALC1546079S.

- Stojkovski, Boris (2020). "Byzantine military campaigns against Serbian lands and Hungary in the second half of the eleventh century.". In Theotokis, Georgios; Meško, Marek (eds.). War in Eleventh-Century Byzantium. Routledge. ISBN 978-0429574771.

- Thurn, Hans, ed. (1973). Ioannis Scylitzae Synopsis historiarum. Berlin-New York: De Gruyter. ISBN 9783110022858.

- Whittow, Mark (1996). The Making of Orthodox Byzantium, 600–1025. Basingstoke: Macmillan. ISBN 9781349247653.

- Живковић, Тибор (2002). Јужни Словени под византијском влашћу 600–1025 (South Slavs under the Byzantine Rule 600–1025). Београд: Историјски институт САНУ, Службени гласник. ISBN 9788677430276.

- Živković, Tibor (2008). Forging unity: The South Slavs between East and West 550–1150. Belgrade: The Institute of History, Čigoja štampa. ISBN 9788675585732.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Raška (region). |